PSI ANNUAL REPORT 2011.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hip # 987-1088

Hip No. Consigned by Tate Farms Hip No. 987 Jess Sizzlin SI 92 987 1997 Sorrel Mare Streakin La Jolla SI 99 {Streakin Six SI 104 Mr Jess Perry SI 113 { Bottom’s Up SI 82 Scoopie Fein SI 99 {Sinn Fein SI 98 Jess Sizzlin SI 92 Legs La Scoop SI 95 3654393 Easy Jet SI 100 {Jet Deck SI 100 Sizzlin Kim SI 86 Lena’s Bar TB SI 95 (1987) { Sun Spots {Double Bid SI 100 Winsum Miss SI 95 By MR JESS PERRY SI 113 (1992). Champion 2-year-old, $687,184 [G1]. Sire of 799 ROM, 107 stakes winners, $39,619,142, incl. champions APOL- LITICAL JESS SI 107 (world champion, $1,399,831, Los Alamitos Derby [G1]), ONE FAMOUS EAGLE SI 101 ($1,387,453 [G1]). Sire of the dams of 46 stakes winners, incl. BODACIOUS DASH SI 101 ($756,495 [G1]), JES A GAME SI 111 ($323,978 [G2]), TERRIFIC SYNERGY SI 92 ($288,066 [RG2]). 1st dam SIZZLIN KIM SI 86, by Easy Jet. Placed to 3. Dam of 7 foals, 6 to race, 3 winners, including– Jess Sizzlin SI 92 (f. by Mr Jess Perry). Stakes placed winner, below. Streakin Kim (f. by Streakin La Jolla). Unplaced. Dam of– Kims Corona SI 97 (g. by Corona Cocktail). 3 wins to 4, $38,666. 2nd dam SUN SPOTS, by Double Bid. Unraced. Dam of 13 starters, 7 ROM, incl.– SUN KISSES SI 102 (f. by Game Plan). 7 wins to 3, $68,935, Shebester Derby, Mystery Derby. Dam of Exquisite Expense SI 99 ($42,264 [G3]). -

Physical Properties of Martian Meteorites: Porosity and Density Measurements

Meteoritics & Planetary Science 42, Nr 12, 2043–2054 (2007) Abstract available online at http://meteoritics.org Physical properties of Martian meteorites: Porosity and density measurements Ian M. COULSON1, 2*, Martin BEECH3, and Wenshuang NIE3 1Solid Earth Studies Laboratory (SESL), Department of Geology, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan S4S 0A2, Canada 2Institut für Geowissenschaften, Universität Tübingen, 72074 Tübingen, Germany 3Campion College, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan S4S 0A2, Canada *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] (Received 11 September 2006; revision accepted 06 June 2007) Abstract–Martian meteorites are fragments of the Martian crust. These samples represent igneous rocks, much like basalt. As such, many laboratory techniques designed for the study of Earth materials have been applied to these meteorites. Despite numerous studies of Martian meteorites, little data exists on their basic structural characteristics, such as porosity or density, information that is important in interpreting their origin, shock modification, and cosmic ray exposure history. Analysis of these meteorites provides both insight into the various lithologies present as well as the impact history of the planet’s surface. We present new data relating to the physical characteristics of twelve Martian meteorites. Porosity was determined via a combination of scanning electron microscope (SEM) imagery/image analysis and helium pycnometry, coupled with a modified Archimedean method for bulk density measurements. Our results show a range in porosity and density values and that porosity tends to increase toward the edge of the sample. Preliminary interpretation of the data demonstrates good agreement between porosity measured at 100× and 300× magnification for the shergottite group, while others exhibit more variability. -

Fine-Grained Antarctic Micrometeorites and Weathered Carbonaceous Chondrites As Possible Analogues of Ceres Surface: Implications on Its Evolution

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 12, EPSC2018-1024, 2018 European Planetary Science Congress 2018 EEuropeaPn PlanetarSy Science CCongress c Author(s) 2018 Fine-grained Antarctic micrometeorites and weathered carbonaceous chondrites as possible analogues of Ceres surface: implications on its evolution. Jacopo Nava (1), Cristian Carli (2), Ernesto Palomba (2), Alessandro Maturilli (3) and Matteo Massironi (1) (1) Università degli studi di Padova – Dipartimento di Geoscienze, Padova, Italy ([email protected]) (2) IAPS-INAF, Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Roma, Italy (3) Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany. Abstract more weathered and are mainly made of jarosite plus Fe-carbonates and Fe-K sulfides. All of these IR spectra of several micrometeorites (MMs) and samples show the constant presence of carbon Antarctic weathered carbonaceous chondrites compound, which can be poorly graphitized C. (AWCCs) have been acquired and compared to Ceres Phyllosilicates are rare. For what concerns the spectra. We propose these samples as possible AWCCs we found the CM2 sample GRA 98005 with analogues of Ceres. This allowed us to define a more weathering grade Ce that had one side exposed to the precise composition of Ceres and to suggest a Antarctic environment, and is thus heavily altered, possible evolution of this body. and one side that has been preserved with a pristine composition. Spectra on the pristine side are flat and almost featureless. On the contrary spectra of the 1. Introduction weathered side tend to have a shape close to the average Ceres spectra. This meteorite, on the Ceres is an icy body with a surface composition close weathered side, is dominated by Fe-oxides, Ca-Fe to the carbonaceous chondrites (CCs) [1] that carbonates, anidrite and gypsum plus enstatite and suffered aqueous alteration [2] and geothermal forsterite. -

VIRVĖ SAVO KARTUVĖMS Kapitalistų Sandėriai Su Komunistais Vytautas Meškauskas

T e oc. oi' 5 □ TL i r. s t r c ba š' 7243 So» Albanv fk., ' yi Chiccęp, III, ‘ 304.29 ; I0TEKA Į -----THE LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEVVSPAPER -------- P.O. BOX 03206 > 6116 ST. CLAIR AVENUE > CLEVELAND, OHIO 44103 Vol.LXIV Balandis - April 19, 1979 Nr.16 *< TAUTINES MINTIES LIETUVIŲ LAIKRAŠTIS VIRVĖ SAVO KARTUVĖMS Kapitalistų sandėriai su komunistais Vytautas Meškauskas Turiu pasakyti, kad Leninas išpranašavo visą proce Konkrečiai kalbant, pereitų są. Leninas, kuris didesnę savo gyvenimo dalį praleido metų prekybos su sovietais Vakaruose, bet ne Rusijoje, kuris geriau pažinojo Vaka apyvarta siekė tik 2.8 biijonus rus kaip Rusiją, visados rašė ir sakė, jog Vakarų kapi dolerių, t.y. tik trečdalį pre talistai padarys viską, kad sustiprintų SSSR ekonomiją. kybos su ... Taiwanu. Biznie Jie konkuruos savo tarpe, kad mums parduoti gerybes rius tačiau vilioja ne tiek da pigiau ir greičiau, tik tam, kad sovietai jas pirktų ne iš bartinės, kiek ateities galimy bės. Šiaip ar taip, Sovietiją vieno, bet iš kito. Jis sakė: jie taip darys negalvodami sudaro rinką su 250 milijonų apie savo pačių ateitį. Vienu sunkiu momentu partijos gyventojų. posėdyje Maskvoje jis drąsino: "Draugai, nepasiduokit Nepaisant to, kad bolševi panikai, jei mums pasidarys labai sunku, mes duosime kai konfiskavo visus užsienie virvę buržuazijai, ir buržuazija pati pasikars." čių kapitalus, buvusius caro Tada, Kari Radek,... kuris buvo labai sąmojingas, Rusijoje - vien Singerio kom paklausė: Vladimire Iličiau, bet iš kur mes paimsime tiek panija prieš karą ten turėjo daug virvės buržuazijos pasikorimui?” Leninas nerūpes 27,000 tarnautojų. Vakarų tingai atsakė: "Jie mus ja aprūpins." kapitalistai padėjo sovietų (Iš Aleksandro Solženicyno 1975 m. -

Pallasites: Olivine-Metal Textures, Phosphoran Olivine, and Origin

Pallasites: olivine-metal textures, phosphoranolivine, and origin Ed Scott University of Hawai’i, Honolulu, HI 96822. [email protected] Four questions: 3. Origin of the four FeO-rich MG pallasites 1. Why do some pallasites have rounded olivines? 2. Why is phosphoran olivine only found in five main-group pallasites? 3. Why do four main group pallasites with rounded olivines contain abnormally Fe-rich olivine? 4. Where did main group and Eagle Station group pallasites form? a 1. Origin of rounded olivine Did cm-sized rounded olivines form before angular olivines [9], or were olivines rounded after Fig. 5. Zaisho, Springwater, Rawlinna, and Phillips Co. fragmentation of olivine [2.3,7]? Constraints: contain anomalously Fe-rich olivine, Ni-rich metal, and • Uniform size distribution of rounded olivines in farringtonite Mg3(PO4)2 [20] suggesting Fe was oxidized. Fig.1c is unlike that of angular olivine pallasites Fig. 3. Ir vs. Ni showing metal in main group pallasites and IIIAB irons. Arrows show Data from [2]. which may contain dunite fragments several cm solid and liquid Fe-Ni paths during fractional crystallization. MG pallasites were b in width (Fig. 1a.). mostly formed by mixing of residual metallic liquid from a IIIAB-like core after 75- Springwater contains 4 • Angular olivine pallasites may contain pieces of 80% crystallization [1,2]. Pavlodar (Pa) has rounded olivines and plots near the vol.% farringtonite (center) rounded olivine texture (Fig. 1b). initial melt composition showing that rounding preceded metal crystallization. enclosing olivine. Slice ~12 • Pavlodar metal matches that expected for initial Marjalahti (Ma), Huckitta (Hu) and Seymchan (Se) have angular olivines and cm wide. -

Aqueous Alteration in Martian Meteorites: Comparing Mineral Relations in Igneous-Rock Weathering of Martian Meteorites and in the Sedimentary Cycle of Mars

AQUEOUS ALTERATION IN MARTIAN METEORITES: COMPARING MINERAL RELATIONS IN IGNEOUS-ROCK WEATHERING OF MARTIAN METEORITES AND IN THE SEDIMENTARY CYCLE OF MARS MICHAEL A. VELBEL Department of Geological Sciences, 206 Natural Science Building, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan 48824-1115 USA e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Many of the minerals observed or inferred to occur in the sediments and sedimentary rocks of Mars, from a variety of Mars-mission spacecraft data, also occur in Martian meteorites. Even Martian meteorites recovered after some exposure to terrestrial weathering can preserve preterrestrial evaporite minerals and useful information about aqueous alteration on Mars, but the textures and textural contexts of such minerals must be examined carefully to distinguish preterrestrial evaporite minerals from occurrences of similar minerals redistributed or formed by terrestrial processes. Textural analysis using terrestrial microscopy provides strong and compelling evidence for preterrestrial aqueous alteration products in a numberof Martian meteorites. Occurrences of corroded primary rock-forming minerals and alteration products in meteorites from Mars cover a range of ages of mineral–water interaction, from ca. 3.9 Ga (approximately mid-Noachian), through one or more episodes after ca. 1.3 Ga (approximately mid–late Amazonian), through the last half billion years (late Amazonian alteration in young shergottites), to quite recent. These occurrences record broadly similar aqueous corrosion processes and formation of soluble weathering products over a broad range of times in the paleoenvironmental history of the surface of Mars. Many of the same minerals (smectite-group clay minerals, Ca-sulfates, Mg-sulfates, and the K-Fe–sulfate jarosite) have been identified both in the Martian meteorites and from remote sensing of the Martian surface. -

Appendix I Lunar and Martian Nomenclature

APPENDIX I LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE LUNAR AND MARTIAN NOMENCLATURE A large number of names of craters and other features on the Moon and Mars, were accepted by the IAU General Assemblies X (Moscow, 1958), XI (Berkeley, 1961), XII (Hamburg, 1964), XIV (Brighton, 1970), and XV (Sydney, 1973). The names were suggested by the appropriate IAU Commissions (16 and 17). In particular the Lunar names accepted at the XIVth and XVth General Assemblies were recommended by the 'Working Group on Lunar Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr D. H. Menzel. The Martian names were suggested by the 'Working Group on Martian Nomenclature' under the Chairmanship of Dr G. de Vaucouleurs. At the XVth General Assembly a new 'Working Group on Planetary System Nomenclature' was formed (Chairman: Dr P. M. Millman) comprising various Task Groups, one for each particular subject. For further references see: [AU Trans. X, 259-263, 1960; XIB, 236-238, 1962; Xlffi, 203-204, 1966; xnffi, 99-105, 1968; XIVB, 63, 129, 139, 1971; Space Sci. Rev. 12, 136-186, 1971. Because at the recent General Assemblies some small changes, or corrections, were made, the complete list of Lunar and Martian Topographic Features is published here. Table 1 Lunar Craters Abbe 58S,174E Balboa 19N,83W Abbot 6N,55E Baldet 54S, 151W Abel 34S,85E Balmer 20S,70E Abul Wafa 2N,ll7E Banachiewicz 5N,80E Adams 32S,69E Banting 26N,16E Aitken 17S,173E Barbier 248, 158E AI-Biruni 18N,93E Barnard 30S,86E Alden 24S, lllE Barringer 29S,151W Aldrin I.4N,22.1E Bartels 24N,90W Alekhin 68S,131W Becquerei -

PERIDOT from TANZANIA by Carol M

PERIDOT FROM TANZANIA By Carol M. Stockton and D. Vincent Manson Peridot from a new locality, Tanzania, is described Duplex I1 refractometer and sodium light, approx- and compared with 13 other peridots from various imate a = 1.650, B = 1.658, and -y = 1.684, indi- localities in terms of color and chemical com- cating a biaxial positive optic character. The position. The Tanzanian specimen is lower in iron specific gravity, measured hydrostatically, is ap- content than all but the Norwegian peridots and is proximately 3.25. very similar to material from Zabargad, Egypt. A gem-quality enstatite that came from the same area CHEMISTRY in East Africa and with which Tanzanian peridot has been confused is also described. The Tanzanian peridot was analyzed using a MAC electron microprobe at an operating voltage of 15 KeV and beam current of 0.05 PA. The standards used were periclase for MgO, kyanite for Ala, quartz for SiOz, wollastonite for CaO, rutile for In September 1982, Dr. Horst Krupp, of Idar- TiOa, chromic oxide for CraOg, almandine-spes- Oberstein, sent GIA's Department of Research a sartine garnet for MnO, fayalite for FeO, and nickel sample of peridot for study. The stone was from oxide for NiO. The data were corrected using the a parcel that supposedly contained enstatite pur- Ultimate correction program (Chodos et al., 1973). chased from the Tanzanian State Gem Corpora- For purposes of comparison, we also selected tion, the source of a previous lot of enstatite that and analyzed peridots from major known locali- Dr. Krupp had already cut and marketed. -

A New Primitive Achondrite from Northwest Africa

A New Primitive Achondrite from Northwest Africa Kseniya K. Androsova* University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada [email protected] and Alan R. Hildebrand University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada Summary The winonaite and acapulcoite/lodranite meteorites constitute small groups of primitive achondrites that have experienced thermal metamorphism sometimes accompanied by varying degrees of partial melting. Petrographic and elemental abundance studies [optical microscope observations and electron microprobe analysis] have been conducted on several meteorites recovered in Northwest Africa (NWA). One meteorite has fine-grained, granulitic texture, abundant, evenly distributed metal and troilite grains, and highly reduced mineral compositions [Olivine (Fa6.0±0.4), low-Ca pyroxene (Fs7.5±0.4, Wo1.3±0.2), high-Ca pyroxene (Fs3.2±0.2, Wo45.8±0.7)]. Based on these criteria it appears that the data are consistent with the sample being a winonaite. The overall textural resemblance of this meteorite to NWA 1463 and /or NWA 725 (somewhat anomalous) winonaites (both having multiple relict chondrules) may suggest that this meteorite is paired with one or both. Although, until its oxygen isotope composition is obtained the classification of this meteorite as a winonaite (vs. as an acapulcoite) remains uncertain, its primitive achondritic nature is quite evident. Introduction The winonaite meteorites represent a class of rare primitive achondrites (together with the acapulcoite/lodranite association) that have sometimes undergone partial melting but generally have chondritic mineralogy and composition. Winonaites can be characterized by fine- to medium-grained, mostly granulitic textures, highly reduced mineral compositions, and unique oxygen isotope signatures (Benedix et al., 1998). Although most of the winonaites lack chondrules, several have been reported to have regions containing relict chondrules. -

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof

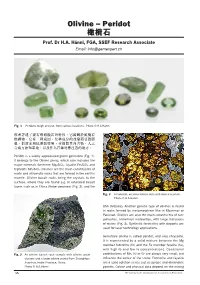

Olivine – Peridot 橄欖石 Prof. Dr H.A. Hänni, FGA, SSEF Research Associate Email: [email protected] Fig. 1 Peridots rough and cut, from various locations. Photo © H.A.Hänni 作者述了寶石級橄欖石的特性,它歸屬於橄欖石 類礦物,它有三種成因,化學成的改變而引致顏 色、折射率和比重的變異,並簡報其內含物、人工 合成方法和產地,以及作為首飾時應注意的地方。 Peridot is a widely appreciated green gemstone (Fig. 1). It belongs to the Olivine group, which also includes the major minerals forsterite Mg2SiO4, fayalite Fe2SiO4 and tephroite Mn2SiO4. Olivines are the main constituents of maic and ultramaic rocks that are formed in the earth’s mantle. Olivine-basalt rocks bring the crystals to the surface, where they are found e.g. in extended basalt layers such as in China (Hebei province) (Fig. 2), and the Fig. 3 A Pallasite, an iron-nickel matrix with olivine crystals. Photo © H.A.Hänni USA (Arizona). Another genetic type of olivines is found in rocks formed by metamorphism like in Myanmar or Pakistan. Olivines are also the main constituents of rare pallasites, nickel-iron meteorites, with large inclusions of olivine (Fig. 3). Synthetic forsterites with dopants are used for laser technology applications. Gemstone olivine is called peridot, and also chrysolite. It is represented by a solid mixture between the Mg member forsterite (fo) and the Fe member fayalite (fa), with high fo and low fa concentrations. Occasional Fig. 2 An olivine-basalt rock sample with olivine grain contributions of Mn, Ni or Cr are always very small, but clusters and a larger olivine crystal from Zhangjikou- inluence the colour of the stone. Forsterite and fayalite Xuanhua, Hebei Province, China. are a solid solution series just as pyrope and almandine Photo © H.A.Hänni garnets. -

Forsterite Dissolution and Magnesite Precipitation at Conditions Relevant for Deep Saline Aquifer Storage and Sequestration of Carbon Dioxide

Chemical Geology 217 (2005) 257–276 www.elsevier.com/locate/chemgeo Forsterite dissolution and magnesite precipitation at conditions relevant for deep saline aquifer storage and sequestration of carbon dioxide Daniel E. Giammara,T, Robert G. Bruant Jr.b, Catherine A. Petersb aDepartment of Civil Engineering and Environmental Engineering Science Program, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63130, United States bProgram in Environmental Engineering and Water Resources, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, United States Received 30 April 2003; accepted 10 December 2004 Abstract The products of forsterite dissolution and the conditions favorable for magnesite precipitation have been investigated in experiments conducted at temperature and pressure conditions relevant to geologic carbon sequestration in deep saline aquifers. Although forsterite is not a common mineral in deep saline aquifers, the experiments offer insights into the effects of relevant temperatures and PCO2 levels on silicate mineral dissolution and subsequent carbonate precipitation. Mineral suspensions and aqueous solutions were reacted at 30 8C and 95 8C in batch reactors, and at each temperature experiments were conducted with headspaces containing fixed PCO2 values of 1 and 100 bar. Reaction products and progress were determined by elemental analysis of the dissolved phase, geochemical modeling, and analysis of the solid phase using scanning electron microscopy, infrared spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction. The extent of forsterite dissolution increased with both increasing temperature and PCO2. The release of Mg and Si from forsterite was stoichiometric, but the Si concentration was ultimately controlled by the solubility of amorphous silica. During forsterite dissolution initiated in deionized water, the aqueous solution reached supersaturated conditions with respect to magnesite; however, magnesite precipitation was not observed for reaction times of nearly four weeks. -

12.109 Lecture Notes September 29, 2005 Thermodynamics II Phase

12.109 Lecture Notes September 29, 2005 Thermodynamics II Phase diagrams and exchange reactions Handouts: using phase diagrams, from 12.104, Thermometry and Barometry Fractional crystallization vs. equilibrium crystallization Perfect equilibrium – constant bulk composition, crystals + melt react, reactions go to equilibrium Perfect fractional – situation where reaction between phases is incomplete, melt entirely removed, etc. Because earth is not in equilibrium, we have interesting geology! Binary system = 2 component system Example: albite (Ab) and anorthite (An) solid solution Phase diagrams show the equilibrium case. Fractional crystallization would result in zoned crystal growth: The exchange of ions happens by solid state diffusion. If the crystal grows faster than ions can diffuse through it, the outer layers form with different compositions, thus we have a chemically zoned crystal. Olivine and plagioclase commonly grow this way. In crossed polarized light, you can see gradual extinction from the center, out to the edges of the crystal. This is also sometimes visible in clinopyroxene. Fractional crystallization preserves the original composition. The center zone has the composition of the crystal from the liquidus. The liquidus composition reveals the temperature of the liquid when it arrived at the final crystallization. Solvus, or miscibility gap – in system with solid solution, region of immiscibility (inability to mix) In Na-K feldspars, perthite results from unmixing of a single crystalline phase two coexisting phases with different compositions and same crystal structure As T goes down, two phases separate out (spinoidal decomposition) Feldspar system, see Bowen and Tuttle Thermometry and Barometry Thermobarometer Igneous and metamorphic rocks Uses composition of coexisting minerals to tell us something about T + P Liquidus minerals record temperature (if you can preserve the composition of the liquidus mineral.