Kastoria Art, Patronage, and Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia

XII. The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia by Iakovos D. Michailidis Most of the reports on Greece published by international organisations in the early 1990s spoke of the existence of 200,000 “Macedonians” in the northern part of the country. This “reasonable number”, in the words of the Greek section of the Minority Rights Group, heightened the confusion regarding the Macedonian Question and fuelled insecurity in Greece’s northern provinces.1 This in itself would be of minor importance if the authors of these reports had not insisted on citing statistics from the turn of the century to prove their points: mustering historical ethnological arguments inevitably strengthened the force of their own case and excited the interest of the historians. Tak- ing these reports as its starting-point, this present study will attempt an historical retrospective of the historiography of the early years of the century and a scientific tour d’horizon of the statistics – Greek, Slav and Western European – of that period, and thus endeavour to assess the accuracy of the arguments drawn from them. For Greece, the first three decades of the 20th century were a long period of tur- moil and change. Greek Macedonia at the end of the 1920s presented a totally different picture to that of the immediate post-Liberation period, just after the Balkan Wars. This was due on the one hand to the profound economic and social changes that followed its incorporation into Greece and on the other to the continual and extensive population shifts that marked that period. As has been noted, no fewer than 17 major population movements took place in Macedonia between 1913 and 1925.2 Of these, the most sig- nificant were the Greek-Bulgarian and the Greek-Turkish exchanges of population under the terms, respectively, of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly and the 1923 Lausanne Convention. -

Communication & Visibility Plan

Municipality of Municipality of Research Committee Municipality of University of Western Prespes Devol Nestorio Macedonia Communication & Visibility plan “Sustainable and almost zero-emission communities and the role of public buildings” MIS 5042958 Table of Contents 1. General communication strategy ...................................................................................... 2 1.1. Internal Communications ............................................................................................ 2 1.2. External communications ................................................................................................ 3 2. Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 5 2.1. Overall communication objectives ............................................................................... 5 2.2. Target groups ........................................................................................................................ 5 Within the country(ies) of the Project where the action is implemented 5 Within the EU (as applicable) .................................................................................... 6 2.3. Specific objectives for each target group, related to the action’s objectives and the phases of the project cycle ....................................................................................... 6 3. Communication activities ................................................................................................... -

1 Curriculum Vitae by Konstantinos Moustakas 1. Personal Details

Curriculum vitae by Konstantinos Moustakas 1. Personal details Surname : MOUSTAKAS Forename: KONSTANTINOS Father’s name: PANAGIOTIS Place of birth: Athens, Greece Date of birth: 10 October 1968 Nationality: Greek Marital status: single Address: 6 Patroklou Str., Rethymnon GR-74100, Greece tel. 0030-28310-77335 (job) e-mail: [email protected] 2. Education 2.1. Academic qualifications - PhD in Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK), 2001. - MPhil in Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK), 1993. - First degree in History, University of Ioannina (Greece), 1990. Mark: 8 1/52 out of 10. 2.2. Education details 1986 : Completion of secondary education, mark: 18 9/10 out of 20. Registration at the department of History and Archeology, University of Ioannina (Greece). 1990 (July) : Graduation by the department of History and Archeology, University of Ioannina. First degree specialization: history. Mark: 8 1/52 out of 10. 1991-1992 : Postgraduate studies at the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK). Program of study: MPhil by research. Dissertation title: Byzantine Kastoria. Supervisor: Professor A.A.M. Bryer. Examinors: Dr. J.F. Haldon (internal), Dr. M. Angold (external). 1 1993 (July): Graduation for the degree of MPhil. 1993-96, 1998-2001: Doctoral candidate at the Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies, University of Birmingham (UK). Dissertation topic: The Transition from Late Byzantine to Early Ottoman Southeastern Macedonia (14th – 15th centuries): A Socioeconomic and Demographic Study Supervisors: Professor A.A.M. Bryer, Dr. R. Murphey. Temporary withdrawal between 30-9-1996 and 30-9-1998 due to compulsory military service in Greece. -

An Insight Guide of Prespa Lakes Region Short Description of the Region

An Insight Guide of Prespa Lakes Region Short description of the region Located in the north-western corner of Greece at 850 metres above sea level and surrounded by mountains, the Prespa Lakes region is a natural park of great significance due to its biodiversity and endemic species. Prespa is a trans boundary park shared between Greece, Albania and FYR Macedonia. It only takes a few moments for the receptive visitor to see that they have arrived at a place with its own unique personality. Prespa is for those who love nature and outdoor activities all year round. This is a place to be appreciated with all the senses, as if it had been designed to draw us in, and remind us that we, too, are a part of nature. Prespa is a place where nature, art and history come together in and around the Mikri and Megali Prespa lakes; there are also villages with hospitable inhabitants, always worth a stop on the way to listen to their stories and the histories of the place. The lucky visitor might share in the activities of local people’s daily life, which are all closely connected to the seasons of the year. These activities have, to a large extent, shaped the life in Prespa. The three main traditional occupations in the region are agriculture, animal husbandry and fishing. There are a lot of paths, guiding you into the heart of nature; perhaps up into the high mountains, or to old abandoned villages, which little by little are being returned once more to nature’s embrace. -

Blood Ties: Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878

BLOOD TIES BLOOD TIES Religion, Violence, and the Politics of Nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 I˙pek Yosmaog˘lu Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Copyright © 2014 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2014 by Cornell University Press First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 2014 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yosmaog˘lu, I˙pek, author. Blood ties : religion, violence,. and the politics of nationhood in Ottoman Macedonia, 1878–1908 / Ipek K. Yosmaog˘lu. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5226-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8014-7924-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Macedonia—History—1878–1912. 2. Nationalism—Macedonia—History. 3. Macedonian question. 4. Macedonia—Ethnic relations. 5. Ethnic conflict— Macedonia—History. 6. Political violence—Macedonia—History. I. Title. DR2215.Y67 2013 949.76′01—dc23 2013021661 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Paperback printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To Josh Contents Acknowledgments ix Note on Transliteration xiii Introduction 1 1. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

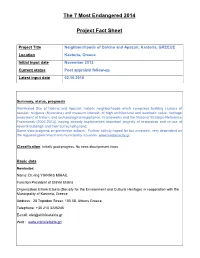

The 7 Most Endangered 2014 Project Fact Sheet

The 7 Most Endangered 2014 Project Fact Sheet Project Title Neighbourhoods of Dolcho and Apozari, Kastoria, GREECE Location Kastoria, Greece Initial input date November 2013 Current status Post appraisal follow-up Latest input date 02.10.2018 Summary, status, prognosis Nominated Site of Dolcho and Apozari, historic neighborhoods which comprises building clusters of secular, religious (Byzantine) and museum interest, of high architectural and aesthetic value, heritage monument of historic and archaeological importance. Frameworks and the National Strategic Reference Framework (2007-2013), having already implemented important projects of restoration and re-use of several buildings and their surrounding land. Some slow progress on preventive actions. Further activity hoped for but uncertain, very dependent on the regional government and municipality situation. www.kastoriacity.gr Classification: Initially good progress. No news about present times. Basic data Nominator: Name: Dr.-Ing YIANNIS MIHAIL Function President of Elliniki Etairia Organization Elliniki Etairia (Society for the Environment and Cultural Heritage) in cooperation with the Municipality of Kastoria, Greece Address : 28 Tripodon Street, 105 58, Athens Greece Telephone: +30 210 3225245 E-mail: [email protected] Web : www.ellinikietairia.gr/ Brief description: Historic neighborhoods with relevant examples of residential small buildings growing around small byzantine chapels and churches. Landscape and surrounding area with high heritage value. Owner: Public. (&Private), Bishopric (churches). 2013 data: Name: Municipality of Kastoria Administrator: (2013 data). The Municipality of Kastoria, with its own funds and resources and with European funds. Other partners: • The Regional Authority of Western Macedonia. Website: www.pdm.gov.gr • The 16th ΕΒΑ (Ephorate of Byzantine Antiquities). • The Technical Chamber of Greece (ΤΕΕ). -

The Attitude of the Communist Party of Greece and the Protection of the Greek-Yugoslav Border

Spyridon Sfetas Autonomist Movements of the Slavophones in 1944: The Attitude of the Communist Party of Greece and the Protection of the Greek-Yugoslav Border The founding of the Slavo-Macedonian Popular Liberation Front (SNOF) in Kastoria in October 1943 and in Florina the following November was a result of two factors: the general negotiations between Tito's envoy in Yugoslav and Greek Macedonia, Svetozar Vukmanovic-Tempo, the military leaders of the Greek Popular Liberation Army (ELAS), and the political leaders of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) in July and August 1943 to co-ordinate the resistance movements; and the more specific discussions between Leonidas Stringos and the political delegate of the GHQ of Yugoslav Macedonia, Cvetko Uzunovski in late August or early September 1943 near Yannitsa. The Yugoslavs’ immediate purpose in founding SNOF was to inculcate a Slavo- Macedonian national consciousness in the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia and to enlist the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia into the resistance movement in Yugoslav Macedonia; while their indirect aim was to promote Yugoslavia's views on the Macedonian Question. The KKE had recognised the Slavophones as a "SlavoMacedonian nation" since 1934, in accordance with the relevant decision by the Comintern, and since 1935 had been demanding full equality for the minorities within the Greek state; and it now acquiesced to the founding of SNOF in the belief that this would draw into the resistance those Slavophones who had been led astray by Bulgarian Fascist propaganda. However, the Central Committee of the Greek National Liberation Front (EAM) had not approved the founding of SNOF, believing that the new organisation would conduce more to the fragmentation than to the unity of the resistance forces. -

The Truth About Greek Occupied Macedonia

TheTruth about Greek Occupied Macedonia By Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov (Translated from Macedonian to English and edited by Risto Stefov) The Truth about Greek Occupied Macedonia Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2017 by Hristo Andonovski & Risto Stefov e-book edition January 7, 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface................................................................................................6 CHAPTER ONE – Struggle for our own School and Church .......8 1. Macedonian texts written with Greek letters .................................9 2. Educators and renaissance men from Southern Macedonia.........15 3. Kukush – Flag bearer of the educational struggle........................21 4. The movement in Meglen Region................................................33 5. Cultural enlightenment movement in Western Macedonia..........38 6. Macedonian and Bulgarian interests collide ................................41 CHAPTER TWO - Armed National Resistance ..........................47 1. The Negush Uprising ...................................................................47 2. Temporary Macedonian government ...........................................49 -

Green-Inter-E-Mobility Press-Release

MUNICIPAL ENTERPRISE OF PRESPA Two on-line meetings of the «Green-Inter-e-Mobility», a project Co-financed by the EU Interreg -IPA CBC Greece-Republic of North Macedonia 2014-2020, with the full title «Integration of Green Transport in Cities», were successfully completed on Thursday, February 25, and Thursday, March 4, 2021, between the Municipal Enterprise of Prespa, the University of Western Macedonia and a representative of the DEEDHE (Hellenic Electricity Distribution Network Operator). During these meetings, the project’s results and progress so far were presented and the participants discussed their upcoming actions. The objectives of the program include the supply, operation and optimal use, with the help of intelligent transport systems, of four electric buses and four electric vehicles for the transportation needs of pupils, the elderly and people with disabilities, in the Municipalities of Florina, Prespes, Bitola and Resen. At the same time, the same number of Photovoltaic powered charging stations will be constructed in each Municipality, for zero emission charging of the vehicles. The Department of Civil Engineering of Patras University, also participates in the program and its team is conducting transportation Studies for the most efficient electric minibuses route schedule, for on-demand transport services of the aforementioned groups of citizens in each Municipality as well as the general population, considering the geographic and demographic features of each Municipality. Project’s Partners: • University of Western Macedonia -

Creating Touristic Itinerary in the Region of Prespa Abstract

International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection Vol. 4, No. 7, 2016 ISSN 2309-0405 CREATING TOURISTIC ITINERARY IN THE REGION OF PRESPA M.Sc. Ema MUSLLI, PhD Candidate University of Tirana ABSTRACT The Prespa Region is located on the Balkan Peninsula, between the countries of Albania, Macedonia and Greece. It includes Greater Prespa Lake and the surrounding beach and meadow areas, designated agricultural use areas and the towns of Pustec, Resen and Prespes. This region is now a part of the Trans-Boundary Biosphere Reserve ‘Ohrid-Prespa Watershed. Greater and Lesser Prespa lakes plus Ohrid Lake are included in the UNESCO world Heritage Site. This area has been known historically for its diverse natural and cultural features. Prespa Region is currently covered by Prespa National Parks in Albania and Greece and Galichica and Pelisteri National Parks in Macedonia. The natural environment and the cultural heritage are a key element designated for the development of the region’s sustainable tourism. This study was enhanced via the Geographic Info System (GIS) digital presentation showing the opportunities for nature tourism in the Pustec and Resen commune. The article also includes two touristic itineraries that will help a better promotion of the tourism in the Prespa Region. Keywords: Touristic potential, cultural heritage, nature heritage, touristic itineraries. INTRODUCTION The Greater Prespa Watershed is located in the southeastern region of Albania and in the southwestern part of Macedonia, in the region of Korçë, commune of Pustec in the Albanian part, in the Resen commune in the Macedonian part and in the Prespe commune in Greece. -

Spyridon Sfetas Autonomist Movements of the Slavophones in 1944

Spyridon Sfetas Autonomist Movements of the Slavophones in 1944: The Attitude of the Communist Party of Greece and the Protection of the Greek-Yugoslav Border The founding of the Slavo-Macedonian Popular Liberation Front (SNOF) in Kastoria in October 1943 and in Florina the following November was a result of two factors: the general negotiations between Tito's envoy in Yugoslav and Greek Macedonia, Svetozar Vukmanovic-Tempo, the military leaders of the Greek Popular Liberation Army (ELAS), and the political leaders of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) in July and August 1943 to co-ordinate the resistance movements1; and the more specific discussions between Leonidas Stringos and the political delegate of the GHQ of Yugoslav Macedonia, Cvetko Uzunovski in late August or early September 1943 near Yannitsa2. The Yugoslavs’ immediate purpose in founding SNOF was to inculcate a Slavo-Macedonian national consciousness in the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia and to enlist the Slavophones of Greek Macedonia into the resistance movement in Yugoslav Macedonia; while their indirect aim was to promote Yugoslavia's views on the Macedonian Question3. The KKE had recognised the Slavophones as a “SlavoMacedonian nation” since 1934, in accordance with the relevant decision by the Comintern, and since 1935 had been demanding full equality for the minorities within the Greek state; and it now acquiesced to the founding of SNOF in the belief that this would draw into the resistance those Slavophones who had been led astray by Bulgarian Fascist propaganda4. However, 1. See T.-A. Papapanagiotou, L’ Effort pourla creation dugland quartiergendral balcanique et la cooperation balcanique, Juin-Septembre 1943 (unpublished postgraduate dissertation, Sorbonne, 1991); there is a copy in the library of the Institute for Balkan Studies, Thessaloniki.