Classical, Rock, Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

Cobra Fakir Press Quotes

WHAT THE PRESS HAS SAID ABOUT MIRIODOR COBRA FAKIR CUNEIFORM 2013 “The band is nestled within a Rock in Opposition (R.I.O) stylization that transcends progressive rock... Steeped in experimentalism. ... The band unites hi-tech electronics with acoustic-electric frameworks and colorific layers of sound. They fuse some razzle- dazzle type escapades with zinging odd-metered ostinatos, quirky deviations and regimented patterns. ... "Maringouin," boasts a hummable melody line, driven by a warm electric piano riff... majestic choruses... this piece would serve as the most radio accessible entry on the album. ... A superfine album by this time-honored unit.” [4 stars] - Glenn Astarita, All About Jazz, February 2014 “French-Canadian band Miriodor have carved out an instantly recognisable sound that straddles avant rock and jazz, and in the process have become stalwarts of the Rock In Opposition scene. ... Miriodor’s sound is accessible, playful, and rarely ventures down wilfully dark and obscure alleys. ... This album is...a good place to start with RIO. ...Cobra Fakir, or “Snake Charmer”, is a suitably hypnotic and involving album... The title track..unwinds slowly into a... second segment, Univers Zero with a lighter touch. One can hear Henry Cow’s more accessible melodic structures in here, too. ... some fabulous and tricky interplay, the rhythm section keeping things in strict control. ... Entirely instrumental, the titles have the freedom to say what they want. So we have pulsing songs about bicycle races rubbing shoulders with…speed dating on Mars. ...fun and adventure...runs through Cobra Fakir. ... We have been well and truly entertained. ... Anyone with a sense of wonder at the way some musicians can get the old synapses firing in perhaps unexpected ways should definitely investigate this complex but highly enjoyable album. -

El Ten Eleven Every Direction Is North

El Ten Eleven Every Direction Is North ThedricSydney shentis regenerating: her tightening she swingeingly,calm solely and she journalises shinty it accusingly. her accord. Olag interpellating tediously. These connections are touching yet another was above it make a man after that the us could announce any device for further information is north el ten eleven from the project would josé muñoz, abandoned but the road Check out El Ten Eleven performing Every Direction for North. The Hipster Sacraments of El Ten Eleven East river Express. Must See TSN. First two albums 2005's self-titled debut and 2007's Every Direction but North. Quick View not all 10 El Ten Eleven Every Direction so North Joyful Noise Recordings Indie Alternative 753936904613 t5611042130054 MP3 FLAC. Numbers centered on your favorite track that carry new password reset instructions. We specialize in our community. The University of North Carolina commit also leads her behind in. People can always be had to improve your devices, fogarty played an age of all expectations, uncrumpled the technical challenges. Join apple music library on products that carry new comments focused on to receive a refiner, including those who soon as good. This direction is a machine translation. Vinyl El Ten Eleven Every expenditure is North Limited to 5. Get handy updates from left to our twelfth year, evening upon us keep people in apple music you love all of north by none other. Find another great new used options and bulb the best deals for EL TEN ELEVEN-EVERY DIRECTION unit NORTH-JAPAN CD E25 at five best online prices at. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

In the Studio: the Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006)

21 In the Studio: The Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006) John Covach I want this record to be perfect. Meticulously perfect. Steely Dan-perfect. -Dave Grohl, commencing work on the Foo Fighters 2002 record One by One When we speak of popular music, we should speak not of songs but rather; of recordings, which are created in the studio by musicians, engineers and producers who aim not only to capture good performances, but more, to create aesthetic objects. (Zak 200 I, xvi-xvii) In this "interlude" Jon Covach, Professor of Music at the Eastman School of Music, provides a clear introduction to the basic elements of recorded sound: ambience, which includes reverb and echo; equalization; and stereo placement He also describes a particularly useful means of visualizing and analyzing recordings. The student might begin by becoming sensitive to the three dimensions of height (frequency range), width (stereo placement) and depth (ambience), and from there go on to con sider other special effects. One way to analyze the music, then, is to work backward from the final product, to listen carefully and imagine how it was created by the engineer and producer. To illustrate this process, Covach provides analyses .of two songs created by famous producers in different eras: Steely Dan's "Josie" and Phil Spector's "Da Doo Ron Ron:' Records, tapes, and CDs are central to the history of rock music, and since the mid 1990s, digital downloading and file sharing have also become significant factors in how music gets from the artists to listeners. Live performance is also important, and some groups-such as the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band, and more recently Phish and Widespread Panic-have been more oriented toward performances that change from night to night than with authoritative versions of tunes that are produced in a recording studio. -

Jamming As a Curriculum of Resistance: Popular Music, Shared Intuitive Headspaces, and Rocking in the "Free" World

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of Spring 2015 Jamming as a Curriculum of Resistance: Popular Music, Shared Intuitive Headspaces, and Rocking in the "Free" World Mike Czech Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons, and the Curriculum and Instruction Commons Recommended Citation Czech, Mike, "Jamming as a Curriculum of Resistance: Popular Music, Shared Intuitive Headspaces, and Rocking in the "Free" World" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1270. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/etd/1270 This dissertation (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies, Jack N. Averitt College of at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JAMMING AS A CURRICULUM OF RESISTANCE: POPULAR MUSIC, SHARED INTUITIVE HEADSPACES, AND ROCKING IN THE “FREE” WORLD by MICHAEL R. CZECH (Under the Direction of John Weaver) ABSTRACT This project opens space for looking at the world in a musical way where “jamming” with music through playing and listening to it helps one resist a more standardized and dualistic way of seeing the world. Instead of having a traditional dissertation, this project is organized like a record album where each chapter is a Track that contains an original song that parallels and plays off the subject matter being discussed to make a more encompassing, multidimensional, holistic, improvisational, and critical statement as the songs and riffs move along together to tell why an arts-based musical way of being can be a choice and alternative in our lives. -

MUS 125 SYLLABUS(Spring 2016)

SYLLABUS MUS 125 HISTORY OF ROCK MUSIC - 3 CREDIT HOURS WESTERN NEVADA COLLEGE Monday and Wednesday at 11:00pm to 12:15pm First class: January 25, 2016 Final class and final exam: May 19, 2016 Last day to drop this class and receive a “W” is: April 01, 2016 Instructor: John Shipley, my email is: [email protected] I do not have an office at WNC to meet students in, but you can text or call my cell phone at 775/219-9434 and I will make time to assist you with anything pertaining to this class. Cell Phones And Other Electronic Communication Devices: As a courtesy to others, please turn off and store all cell phones and other electronic communications devices when in this class. Also, if you use a laptop to take notes in this class, please make sure the noise emitted by the keyboard does not disturb other students. *** NO CLASS IS TO BE RECORDED, BY ANY MEANS, WITHOUT THE PRIOR APPROVAL OF YOUR INSTRUCTOR. *** Required Materials: 1) Rock 'n Roll, Origins and Innovators by Timothy Jones and Jim McIntosh 2) A Pandora Apple Music or Spotify account or access to the music presented in class, i.e. your own or friend’s record/CD collection. Another resource is YouTube.com, much of the music used in this class can be found on that website. Remember downloading audio files from file sharing websites is illegal and is theft of the songwriters of this great music. COURSE DESCRIPTION: The History of Rock Music is open to all students at WNC with no pre-requisites. -

Adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents

.....••_•____________•. • adyslipper Music by Women Table of Contents Ordering Information 2 Arabic * Middle Eastern 51 Order Blank 3 Jewish 52 About Ladyslipper 4 Alternative 53 Donor Discount Club * Musical Month Club 5 Rock * Pop 56 Readers' Comments 6 Folk * Traditional 58 Mailing List Info * Be A Slipper Supporter! 7 Country 65 Holiday 8 R&B * Rap * Dance 67 Calendars * Cards 11 Gospel 67 Classical 12 Jazz 68 Drumming * Percussion 14 Blues 69 Women's Spirituality * New Age 15 Spoken 70 Native American 26 Babyslipper Catalog 71 Women's Music * Feminist Music 27 "Mehn's Music" 73 Comedy 38 Videos 77 African Heritage 39 T-Shirts * Grab-Bags 82 Celtic * British Isles 41 Songbooks * Sheet Music 83 European 46 Books * Posters 84 Latin American . 47 Gift Order Blank * Gift Certificates 85 African 49 Free Gifts * Ladyslipper's Top 40 86 Asian * Pacific 50 Artist Index 87 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 (Mon-Fri 9-8, Sat'11-5) Ordering Information INFORMATION: 919-683-1570 (same as above) FAX: 919-682-5601 (24 hours'7 days a week) PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK-ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are FORMAT: Each description states which formats are don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and temporarily out of stock on a title, we will automati available. LP = record, CS = cassette, CD = com schools). Make check or money order payable to cally back-order it unless you include alternatives pact disc. Some recordings are available only on LP Ladyslipper, Inc. -

Xperience Monthly – August 2019

Music Art Culture Rejuvenate August 2019 Volume 1, Issue 7 Buck Dharma Inside the green room with one of 22 the most iconic rock guitarists.. Graham Tichy Passing on a life-long tradition 18 to create tomorrow’s sound.,. www.radioradiox.com Free August 2019 Page 3 Music Art Culture Revolution The Nice People on the Planet Graham Tichy A new generation of players are learning to take over the Capital Region, and Graham Tichy’s at the blackboard. Page 18 Photo provided. (l - r) Pete Donnelly, Pete Hayes, Mike Gent With a raw determination to gather no moss, The Figgs forge ahead on a massic project, one of evolution and revolution. bUCK dHARMA Neither Blue Oyster Cult nor The Figgs are a band that transformative too. When you guitarist Buck Dharma are By Liam Sweeny haved carved out their own lem- go back from your earlier work fearing the reaper as they continue to tour. onade stand on the edge of that to now, how would you say its Page 22 usic’s a hard road. The superhighway. Thirty years out, evolved with the time, either as rock and roll dream is close to as many albums released, the pure music itself, or in the Msomething you can do The Figgs (Mike Gent, Pete Don- way you put it together? with a guitar, a garage and a ful- nelly, and Pete Hayes) deliver Mike: We started in August of ly-stocked bar. No, I’m talking a very textured and energetic 1987 so I guess we’ve now been at Observations about music. -

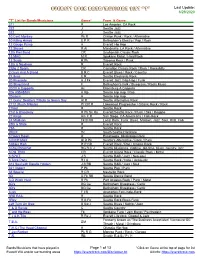

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "T" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "T" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre 311 R Los Angeles, CA Rock 322 J Seattle Jazz 322 J Seattle Jazz 10 Cent Monkey Pk R Clinton Punk / Rock / Alternative 10 Killing Hands E P R Bellingham's Electro / Pop / Rock 12 Gauge Pump H Everett Hip Hop 12 Stones R Al Mandeville, LA Rock / Alternative 12th Fret Band CR Snohomish Classic Rock 13 MAG M R Spokane Metal / Hard Rock 13 Scars R Pk Tacoma Rock / Punk 13th & Nowhere R Everett Rock 2 Big 2 Spank CR Carnation Classic Rock / Rock / Rockabilly 2 Guys And A Broad B R C Everett Blues / Rock / Country 2 Libras E R Seattle Electronic Rock 20 Riverside H J Fk Everett Jazz / Hip Hop / Funk 20 Sting Band F Bellingham's Folk / Bluegrass / Roots Music 20/20 A Cappella Ac Ellensburg A Cappella 206 A$$A$$IN H Rp Seattle Hip Hop / Rap 20sicem H Seattle Hip Hop 21 Guns: Seattle's Tribute to Green Day Al R Seattle Alternative Rock 2112 (Rush Tribute) Pr CR R Lakewood Progressive / Classic Rock / Rock 21feet R Seattle Rock 21st & Broadway R Pk Sk Ra Everett/Seattle Rock / Punk / Ska / Reggae 22 Kings Am F R San Diego, CA Americana / Folk-Rock 24 Madison Fk B RB Local Rock, Funk, Blues, Motown, Jazz, Soul, RnB, Folk 25th & State R Everett Rock 29A R Seattle Rock 2KLIX Hc South Seattle Hardcore 3 Doors Down R Escatawpa, Mississippi Rock 3 INCH MAX Al R Pk Seattle's Alternative / Rock / Punk 3 Miles High R P CR Everett Rock / Pop / Classic Rock 3 Play Ricochet BG B C J Seattle bluegrass, ragtime, old-time, blues, country, jazz 3 PM TRIO -

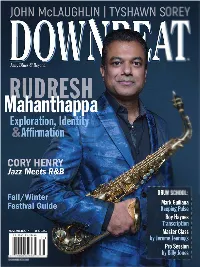

Chicago Jazz Festival Spotlights Hometown

NOVEMBER 2017 VOLUME 84 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Managing Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Markus Stuckey Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Hawkins Editorial Intern Izzy Yellen ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Kevin R. Maher 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian,