Community and Creativity in the Classroom: An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dancin' on Tulsa Time

Dancin’ on Tulsa Time Gonna set my watch back to it…. 42nd ICBDA Convention July 11-14, 2018 Renaissance Hotel & Convention Center Tulsa, Oklahoma ________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Welcome to the 42nd ICBDA Convention 2018 . 1 Welcome from the Chairman of the Board . 2 Convention 43 – Orlando, Florida . 3 Committee Chairs – Convention 42 . 4 2018 Week at a Glance . 5 Cuers and Masters of Ceremony . 9 ICBDA Board of Directors . .10 Distinguished Service Award . 11 Golden Torch Award . 11 Top 15 Convention Dances . .. 12 Top 15 Convention Dances Statistics . 13 Top 10 Dances in Each Phase . 14 Hall of Fame Dances . 15 Video Order Form . 16 Let’s Dance Together – Hall A . 18 Programmed Dances – Hall A . 19 Programmed Dances – Hall B . 20 Programmed Dances – Hall C . 21 Clinic and Dance Instructors . 22 Paula and Warwick Armstrong . 23 Fred and Linda Ayres . 23 Wayne and Barbara Blackford . 24 Mike and Leisa Dawson . 24 John Farquhar and Ruth Howell . 25 Dan and Sandi Finch . 25 Mike and Mary Foral . 26 Ed and Karen Gloodt . 26 Steve and Lori Harris . 27 John and Karen Herr . 27 Tom Hicks . 28 Joe and Pat Hilton . 28 George and Pamela Hurd . 29 i ________________________________________________________________________ Pamela and Jeff Johnson . .29 John and Peg Kincaid . 30 Kay and Bob Kurczweski. 30 Randy Lewis and Debbie Olson . .31 Rick Linden and Nancy Kasznay . 31 Bob and Sally Nolen . 32 J.L. and Linda Pelton . 32 Sue Powell and Loren Brosie . 33 Randy and Marie Preskitt . 33 Mark and Pam Prow . 34 Paul and Linda Robinson . 34 Debbie and Paul Taylor . -

Physical Education Dance (PEDNC) 1

Physical Education Dance (PEDNC) 1 Zumba PHYSICAL EDUCATION DANCE PEDNC 140 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab (PEDNC) A fusion of Latin and international music-dance themes, featuring aerobic/fitness interval training with a combination of fast and slow Ballet-Beginning rhythms that tone and sculpt the body. PEDNC 130 1 Credit/Unit Hula 2 hours of lab PEDNC 141 1 Credit/Unit Beginning ballet technique including barre and centre work. [PE, SE] 2 hours of lab Ballroom Dance: Mixed Focus on Hawaiian traditional dance forms. [PE,SE,GE] PEDNC 131 1-3 Credits/Units African Dance 6 hours of lab PEDNC 142 1 Credit/Unit Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. Develop confidence 2 hours of lab through practice with a variety of partners in both smooth and latin style Introduction to African dance, which focuses on drumming, rhythm, and dances to include: waltz, tango, fox trot, quick step and Viennese waltz, music predominantly of West Africa. [PE,SE,GE] mambo, cha cha, rhumba, samba, salsa. Bollywood Ballroom Dance: Smooth PEDNC 143 1 Credit/Unit PEDNC 132 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab 2 hours of lab Introduction to dances of India, sometimes referred to as Indian Fusion. Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. Develop confidence Dance styles focus on semi-classical, regional, folk, bhangra, and through practice with a variety of partners. Smooth style dances include everything in between--up to westernized contemporary bollywood dance. waltz, tango, fox trot, quick step and Viennese waltz. [PE,SE,GE] [PE,SE,GE] Ballroom Dance: Latin Irish Dance PEDNC 133 1 Credit/Unit PEDNC 144 1 Credit/Unit 2 hours of lab 2 hours of lab Fundamentals, forms and pattern of ballroom dance. -

Groove in Cuban Dance Music: an Analysis of Son and Salsa Thesis

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Thesis How to cite: Poole, Adrian Ian (2013). Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2013 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.0000ef02 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk \ 1f'1f r ' \ I \' '. \ Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Adrian Ian Poole esc MA Department of Music The Open University Submitted for examination towards the award of Doctor of Philosophy on 3 September 2012 Dntc \.?~ ,Sllbm.~'·\\(~·' I ~-'-(F~\:ln'lbCt i( I) D Qt C 0'1 f\;V·J 0 1('\: 7 M (~) 2 013 f1I~ w -;:~ ~ - 4 JUN 2013 ~ Q.. (:. The Library \ 7<{)0. en ~e'1l poo DONATION CO)"l.SlALt CAhon C()F) Iiiiii , III Groove in Cuban Dance Music: An Analysis of Son and Salsa Abstract The rhythmic feel or 'groove' of Cuban dance music is typically characterised by a dynamic rhythmic energy, drive and sense of forward motion that, for those attuned, has the ability to produce heightened emotional responses and evoke engagement and participation through physical movement and dance. -

Round Dances Scot Byars Started Dancing in 1965 in the San Francisco Bay Area

Syllabus of Dance Descriptions STOCKTON FOLK DANCE CAMP – 2016 – FINAL 7/31/2016 In Memoriam Floyd Davis 1927 – 2016 Floyd Davis was born and raised in Modesto. He started dancing in the Modesto/Turlock area in 1947, became one of the teachers for the Modesto Folk Dancers in 1955, and was eventually awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award for dance by the Stanislaus Arts Council. Floyd loved to bake and was famous for his Chocolate Kahlua cake, which he made every year to auction off at the Stockton Folk Dance Camp Wednesday auction. Floyd was tireless in promoting folk dancing and usually danced three times a week – with the Del Valle Folk Dancers in Livermore, the Modesto Folk Dancers and the Village Dancers. In his last years, Alzheimer’s disease robbed him of his extensive knowledge and memory of hundreds, if not thousands, of folk dances. A celebration for his 89th birthday was held at the Carnegie Arts Center in Turlock on January 29 and was attended by many of his well-wishers from all over northern California. Although Floyd could not attend, a DVD was made of the event and he was able to view it and he enjoyed seeing familiar faces from his dancing days. He died less than a month later. Floyd missed attending Stockton Folk Dance Camp only once between 1970 and 2013. Sidney Messer 1926 – 2015 Sidney Messer died in November, 2015, at the age of 89. Many California folk dancers will remember his name because theny sent checks for their Federation membership to him for nine years. -

June 2 15 Phoenix AZ 85032 602.324.7119 * Al Ro M S De [email protected] Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat

Fatcat Ballroom & Dance Company 3131 E Thunderbird Road, #33 June 2 15 Phoenix AZ 85032 602.324.7119 www.FatcatBallroomDance.com * al ro m S de [email protected] Sun Mon Tues Wed Thurs Fri Sat Ballroom 1 5:30 - 6:30 2 3 4 5 6 12:00 - 3:30 Argentine Tango East Coast Country Night West Coast Swing Milonga Dance Silver & Gold After w/Terry Swing Night w/Mona w/Mona $7 Lesson/Party/$7 Rhumba Church! 6:30 - 7:30 7:00 Basic West Coast w/Terry Argentine Tango $7 $7 Swing w/Bridgette & Ballroom Dance w/Helmut 7:00 Beg. Sunday 7:30 Swing 7:45 Int. West Coast Jaime Lesson/Party-$5 6:30 - 8:30 Country Cha Cha Swing Lesson 7:30 Beg. Arg. w/Terry 2:00-4:00 Arizona Ballroom 7:45 Int Country 8:30 WCS Party Tango Teachers’ Academy w/Steve Conrad 6:30 - 8:30 7:30 Beg. Hustle Cha Cha 8:15 Int. Arg. All Churches 7:30-9:30 8:30 ECS Party 8:30 Arizona Ballroom 8:15 Int. Hustle Teachers’ Academy Tango Argentine Tango Dance Party 9pm Dance Party Welcome Practica Semester 1 9pm Dance Party 7 Swing 8 5:30 - 6:30 9 10 11 12 13 12:00 - 3:30 Sunday School Argentine Tango East Coast Country Night West Coast Latin Dance Silver & Gold w/Terry w/Mona Swing w/Mona $7 Lesson/Party/$7 Rhumba w/Steve Conrad 6:30 - 7:30 Swing Night 7:00 Basic West w/Terry 3:00- 6:00 Argentine Tango $7 $7 Coast Swing w/Bridgette & w/Helmut 7:30 Swing 7:00 Beg. -

Latin Rhythm from Mambo to Hip Hop

Latin Rhythm From Mambo to Hip Hop Introductory Essay Professor Juan Flores, Latino Studies, Department of Social and Cultural Analysis, New York University In the latter half of the 20th century, with immigration from South America and the Caribbean increasing every decade, Latin sounds influenced American popular music: jazz, rock, rhythm and blues, and even country music. In the 1930s and 40s, dance halls often had a Latin orchestra alternate with a big band. Latin music had Americans dancing -- the samba, paso doble, and rumba -- and, in three distinct waves of immense popularity, the mambo, cha-cha and salsa. The “Spanish tinge” made its way also into the popular music of the 50s and beyond, as artists from The Diamonds (“Little Darling”) to the Beatles (“And I Love Her”) used a distinctive Latin beat in their hit songs. The growing appeal of Latin music was evident in the late 1940s and 50s, when mambo was all the rage, attracting dance audiences of all backgrounds throughout the United States, and giving Latinos unprecedented cultural visibility. Mambo, an elaboration on traditional Cuban dance forms like el danzón, la charanga and el son, took strongest root in New York City, where it reached the peak of its artistic expression in the performances and recordings of bandleader Machito (Frank Grillo) and his big-band orchestra, Machito and His Afro-Cubans. Machito’s band is often considered the greatest in the history of Latin music. Along with rival bandleaders Tito Rodríguez and Tito Puente, Machito was part of what came to be called the Big Three. -

THE FIRST 50 YEARS of RDTA of SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA (Highlights Compiled from Minutes of Meetings, Recollections of Charter Members, and Memorabilia)

THE FIRST 50 YEARS OF RDTA of SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA (Highlights Compiled from Minutes of Meetings, Recollections of Charter Members, and Memorabilia) The Round Dance Teachers Association of Southern California, formed in October 1952, was the first organization of its kind in the United States and at one time the largest. It was the first round dance organization to adopt its own manual of standardized figures, long before any national organization came into being. Its manual was the basis for the Roundalab (RAL) Manual of Standards after that organization was founded in 1977. RDTA came about because two local teachers released different dances to The Tennessee Waltz at the same time. At the time, round dancing was considered part of square dancing, not a separate activity and did not have a separate organization. To resolve the problem, one of the two choreographers, Helen Horne, asked members of the regional square dance association to meet to talk about how to avoid such duplication. A few individuals met in June 1952 at the 3 Sisters Ballroom in Temple City to consider setting up a clearing house for routines and to air square dance complaints about round dancing. After two meetings, seven of them proposed a separate round dance organization to standardize round dance terms, provide a forum to share experiences and to encourage cooperation among teachers.1 Many local square dance callers objected, saying round dancing should stay a part of square dancing. Who knows if the impasse would have been broken—but about that time, the ballroom dance industry sought legislation to require teachers of round dance and square dance to be licensed by the state. -

Ceroc® New Zealand Competition Rules, Categories and Judging Criteria

Version: April 2018 Ceroc® New Zealand Competition Rules, Categories and Judging Criteria Ceroc® competition events are held in different regions across New Zealand. The rules for the Classic and Cabaret categories as set out in this document will apply across all of these events. Event organisers will provide clear details for all Creative category rules, which may differ between events. Not all categories listed below will necessarily be present at every event. Each event may have their own extra regional Creative categories that will be detailed on the event organiser’s web pages, which can be found via www.cerocevents.co.nz. Contact the event organiser for further details of categories not listed in this document. Contents 1 Responsibilities 1.1 Organiser Responsibilities 1.2 Competitor Responsibilities 2 Points System for Competitor Levels 2.1 How it works 2.2 Points Registry 2.3 Points as they relate to Competitor Level 2.4 Earning Points 2.5 Teachers Points 2.6 International Competitors 3 General Rules 3.1 Ceroc® Style 3.2 Non-Contact Dancing 3.3 Floorcraft 3.4 Aerials 3.5 Newcomer Moves 4 Classic Categories 4.1 Freestyle 4.2 Dance With A Stranger (DWAS) 5 Cabaret Categories 5.1 Showcase 5.2 Newcomer Teams 5.3 Intermediate and Advanced Teams 6 Creative Categories 6.1 to 6.15 7 Judging 7.1 Judging Criteria 7.2 Penalties and Disqualifications Version: April 2018 1 Responsibilities 1.1 Organiser Responsibilities The organiser is responsible for ensuring the event is run professionally and fairly. This is a complex undertaking and more information can be provided by the organiser or Ceroc® Dance New Zealand (Ceroc® NZ) upon request. -

Newsletter for February 14, 2016

Newsletter for February 14, 2016 From Kathy and Bob Estep, Swinging Stars Presidents: Our first dance as Club Presidents has come and gone. We survived. Hope you feel that way also! Thank you for the 82 members that attended this week. This coming week our Official Visitation is with the Rebel Rousers in Richardson. It is their Black and White Ball and always a lot of fun. Please come join your fellow members on this visitation. Kathy and Bob Happening This Week Tuesday, Feb. 16 – Round Dance Lessons - 7:15PM to 9:15PM - Carpenter Rec. Center - Plano. Tuesday, Feb. 16 – Square Dance Lessons - 7:15PM to 9:15PM - Carpenter Rec. Center - Plano. Wednesday, Feb. 17 – Ladies Lunch – Chocolate Angel, 800 N Central Expy, Plano, TX 75074 Wednesday, Feb. 17 – Plus 4’s – 7:30 PM – 9:30 PM - Quisenberry Saturday, Feb. 20 – Official DD – Rebel Rousers – Richardson Senior Center Announcements Dance Format: Effective immediately our Dance Format will be as follows: 2nd Friday: Square Dance Workshop from 7 - 7:44 pm – at 7:45 the first Plus Tip – 8:00 PM will be the Grand March and first Mainstream Tip – The Second Tip will be Plus – the remainder of the dance will be Mainstream 4th Friday: Round Dance Workshop from 7 - 7:44 pm – at 7:45 the first Plus Tip – 8:00 PM will be the Grand March and first Mainstream Tip – The Second Tip will be Plus – the remainder of the dance will be Mainstream The Hot Hash which follows the last regular Tip will be maintained as long as there is sufficient dancers wishing to participate. -

Cuban Rumba Box (La Rumba De Cajón Cubana) © Jorge Luis Santo - London, England 2007

(La Rumba de Cajón Cubana) Jorge Luis Santo The Cuban Rumba Box (La Rumba de Cajón Cubana) © Jorge Luis Santo - London, England 2007 Cover illustration: Musicians from the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional de Cuba. Left, Ignacio Guerra, right, Ramiro Hernández. From a photograph by the author taken in Havana, Cuba. Back sleeve portrait by Caroline Forbes, UK PREFACE uban music has had a phenomenal global cultural impact. It is a C mixture of African and European influences, and it’s the fusion of these elements that has resulted in a fascinating mosaic of musical forms. The world’s interest in this music has increased over the past few years. Cuba’s musical culture has become much more exposed due to the riches and dynamics it possesses. It attracts people from every walk of life, awakening curiosity among those with the desire to learn, and is slowly making its presence felt in educational circles. However, it continues to be a subject of academic bewilderment due to a lack of knowledge and basic technical skills, also a shortage of qualified teachers in this field. The purpose of this work is to contribute to an understanding and appreciation of Cuban percussion and culture, in particular the Rumba, a Cuban musical genre traditionally played on cajones (boxes) known as the Cuban Rumba Box, presented in a way that seeks to be readable and informative to everyone. It begins with a brief background to the history of the Cuban Rumba and an explanation of the different musical types and styles. A full graphic description of the percussion instruments used to play Rumba is described in the chapter entitled, ‘Design and Technology’. -

Programme Ideas: Physical Section

PHYSICAL Programme ideas: Physical section When completing each section of your DofE, you It’s your choice… should develop a programme which is specific Doing physical activity is fun and improves your and relevant to you. This sheet gives you a list health and physical fitness. There’s an activity to of programme ideas that you could do or you suit everyone so choose something you are really could use it as a starting point to create a Physical interested in. programme of your own! Help with planning For each idea, there is a useful document You can use the handy programme planner on giving you guidance on how to do it, which the website to work with your Leader to plan you can find under the category finder on your activity. www.DofE.org/physical Individual sports: Swimming Fitness: Martial arts: Kabaddi Archery Synchronised Aerobics Aikido Korfball Athletics (any field or swimming Cheerleading Capoeira Lacrosse track event) Windsurfing Fitness classes Ju Jitsu Netball Biathlon/Triathlon/ Gym work Judo Octopushing Pentathlon Dance: Gymnastics Karate Polo Bowling Ballet Medau movement Self-defence Rogaining Boxing Ballroom dancing Physical Sumo Rounders Croquet Belly dancing achievement Tae Kwon Do Rugby Cross country Bhangra dancing Pilates Tai Chi Sledge hockey running Ceroc Running/jogging Stoolball Cycling Contra dance Trampolining Tchoukball Fencing Country & Western Walking Team sports: Ultimate flying disc Golf Flamenco Weightlifting American football Underwater rugby Horse riding Folk dancing Yoga Baseball Volleyball Modern pentathlon -

Jive Nation Poland Ltd and Its Associates Reserve the Right to Change the Programme and Competition If Necessary Without Consultation

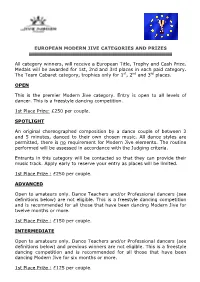

EUROPEAN MODERN JIVE CATEGORIES AND PRIZES All category winners, will receive a European Title, Trophy and Cash Prize. Medals will be awarded for 1st, 2nd and 3rd places in each paid category. The Team Cabaret category, trophies only for 1st, 2nd and 3rd places. OPEN This is the premier Modern Jive category. Entry is open to all levels of dancer. This is a freestyle dancing competition. 1st Place Prize: £250 per couple. SPOTLIGHT An original choreographed composition by a dance couple of between 3 and 5 minutes, danced to their own chosen music. All dance styles are permitted, there is no requirement for Modern Jive elements. The routine performed will be assessed in accordance with the Judging criteria. Entrants in this category will be contacted so that they can provide their music track. Apply early to reserve your entry as places will be limited. 1st Place Prize : £250 per couple. ADVANCED Open to amateurs only. Dance Teachers and/or Professional dancers (see definitions below) are not eligible. This is a freestyle dancing competition and is recommended for all those that have been dancing Modern Jive for twelve months or more. 1st Place Prize : £150 per couple. INTERMEDIATE Open to amateurs only. Dance Teachers and/or Professional dancers (see definitions below) and previous winners are not eligible. This is a freestyle dancing competition and is recommended for all those that have been dancing Modern Jive for six months or more. 1st Place Prize : £125 per couple. EUROPEAN MODERN JIVE CATEGORIES AND PRIZES RISING STARS Open to amateurs only. Dance Teachers and/or Professional dancers (see definitions below) and previous winners are not eligible.