Copyright Protection for Perfumes*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let the Holidays Begin! Big,Bold Jewels Your Own Shopping the World

D D NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2013 NOVEMBER/DECEMBER Big, Bold Your Own Shopping ...Let the Jewels Private Caribbean the World Holidays Begin! p236 p66 p148 PERSONALBEST the business of scent A Whiff of Something Real As mass-produced perfumes become the new normal, the origin of a fragrance is more important than ever. TINA GAUDOIN reports from Grasse, the ancient home of perfume and the jasmine fields of Chanel No 5. oseph Mul drives his battered pickup into the dusty, rutted field of Jasminum gran- diflorum shrubs. It is 9 A.M. on a warm, slightly overcast September morning in Pégomas in southern France, about four miles from Grasse, the ancient home of Jperfume. In front of Mul’s truck, which is making easy work of the tough ter- rain, a small army of colorfully dressed pickers, most hailing from Eastern Europe, fans out, backs bent in pursuit of the elusive jasmine bloom that flowers over- night and must be harvested from the three-foot-high bushes before noon. By lunchtime, the petals will have been weighed by Mul, the numbers noted in the ledger (bonuses are paid by the kilo), and the pickers, who have been working since before dawn, will retire for a meal and a nap. Not so for Mul, who will oversee the beginnings of the lengthy distillation technique of turning the blooms into jasmine absolute, the essential oil and vital in- gredient in the world’s most famous and best- selling fragrance: Chanel No 5. All told, it’s a labor-intensive process. One picker takes roughly an hour to harvest one pound of jasmine; 772 pounds are required to make two pounds of concrete—the solution ARCHIVE ! WICKHAM/TRUNK ! MICHAEL !"! LTD ! NAST ! The post–World War II era marked the beginning of mass fragrance, when women wore perfume for more than just special occasions. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Foreword Letter from the Chairman 4 Letter from the CEO 6 Fragrance Division 9 Fine Fragrances 11 Consumer Products 12 Fragrance Ingredients 13 Flavour Division 15 Asia Pacific 16 North America 17 Europe, Africa and Middle East 17 Latin America 17 Research and Development 19 Fragrances 21 Flavours 22 Corporate Activities and Organisation 25 GivaudanAccessTM 26 Safety and Environmental Protection 27 Human Resources 28 Corporate Governance 30 Givaudan Securities 35 Financial Review 38 Consolidated Financial Statements 39 Consolidated Income Statement 39 Consolidated Balance Sheet 40 Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 41 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 42 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 43 Report of the Group Auditors 71 Pro forma Condensed Consolidated Income Statement (unaudited) 72 Pro forma Condensed Consolidated Income Statement 72 Notes to the Pro forma Condensed Consolidated Income Statement 73 Statutory Financial Statements of Givaudan SA 74 (Group Holding Company) Income Statement 74 Balance Sheet 75 Notes to the Financial Statements 76 Appropriation of Available Earnings of Givaudan SA 78 Report of the Statutory Auditors 79 Givaudan World-wide 81 Givaudan - Annual Report 2001 1 Traveller’s Tree The endemic Ravenala madagascariensis has been named the Traveller’s Tree because around one litre of water is accumulated in each leaf base. This water is very useful for travellers in an emergency; and if you are in such a situation and have to cut one of the stalks at the base with your machete, you may additionally enjoy a refreshing green and somewhat floral scent. It is said that a traveller in need, standing in front of the tree and making a wish, will have this wish fulfilled. -

Storied Perfume for Mystery Writers, Fragrance Is Often the Most Telltale Clue Left Behind at the Scene of a Crime

latimes.com LA STO RIES LA STYLE LA LIVING LA CULTURE LA BLO G S LA VIDEO S INSIDE L.A. BROWS E Past Issues Topics SEARCH S E P T E M B E R 2 0 1 1 Storied Perfume For mystery writers, fragrance is often the most telltale clue left behind at the scene of a crime UNCOMMON SCENTS In the early stages of evolution, humans whose noses excelled at tracking prey—and could lead their tribe to water and alert it to big, musky predators—were rewarded with both survival and mates. DENISE HAMILTON Scientists say that while we can still distinguish up to 50,000 smells, the need for keen sniffers has dwindled in real life. And yet it flourishes in literature—especially crime fiction, where authors utilize fragrance as clues, psychological triggers and objects of obsession. Best known of the books is probably Patrick Süskind’s 1985 novel (and subsequent movie) Perfume: The Story of a Murderer, about an 18thcentury French idiot savant with olfactory perfect pitch who whips up a scent from the essence of a beautiful virgin that he has sniffed out in a secluded private garden, and the resulting odor is able to bewitch people into doing his bidding. Perfume is redolent with antique apothecaries, fragrant Grasse flower fields and enfleurage, the process of using odorless fats to capture the fragrant compounds that are exuded by plants. But crime novels featuring perfumes reach back to the 1920s and ’30s, the golden age of the classic French perfume houses. When sleuth Philo Vance sniffs the nozzle of an atomizer in a murdered lady’s bathroom in 1934’s Casino Murder Case, author S.S. -

Hugo Boss Won Three of the Four Dolce & Gabbana, Parfum Sparkle of Fruit with a Warm DEVELOPMENTS Cairo Shopping Fifi Awards for Men’S Fragrances in 2003

product. Charles Reaching out to the segment of more than Schumann, the model 35 million people under the age of 25 in Egypt, for the fragrance’s Hugo recently sponsored a welcome party at campaign, has been the American University in Cairo that embodied the face of the the spirit of the modern generation. Students Baldessarini fashion collection for the last four years. His range of Boss fragrances has lifestyle and success struck a chord with successful as the proprietor men and women. of Schumann’s in Boss Bottled, introduced Munich - one of in 1998, represents the most famous enjoyed fragrances contemporary masculinity bars in Europe and samples during the that reconciles apparently where the campaign three-day event. Prestige Distribution, one of the largest local Distribution also represents such conflicting concepts: brains was shot – perfectly “Work hard, fragrance agents. prestigious brands as the Yves and guts, knowledge and represents the play hard” was the Saint Laurent Beauté Group, feeling, reason and emotion. brand. theme of a giant ACHIEVEMENTS Max Factor cosmetics, Kenzo, A multifaceted fragrance, board game played A testament to its innovation and international Puig, Sogedimo, Moschino, it combines a cool, fresh RECENT out at two popular popularity, Hugo Boss won three of the four Dolce & Gabbana, Parfum sparkle of fruit with a warm DEVELOPMENTS Cairo shopping Fifi Awards for men’s fragrances in 2003. In the Balmain and Loewe. sensuous undertone. It is an Boss Intense, the centers, the Serag Haute Couture category, Baldessarini Hugo Boss unmistakable masculine scent newest addition to and Akkad malls. won both Best Parfum and Best Flacon for a new PRODUCT for the man who redefines success, self-confident the women’s fragrance line-up was launched Staged outside the launch. -

Coco Chanel's Comeback Fashions Reflect

CRITICS SCOFFED BUT WOMEN BOUGHT: COCO CHANEL’S COMEBACK FASHIONS REFLECT THE DESIRES OF THE 1950S AMERICAN WOMAN By Christina George The date was February 5, 1954. The time—l2:00 P.M.1 The place—Paris, France. The event—world renowned fashion designer Gabriel “Coco” Cha- nel’s comeback fashion show. Fashion editors, designers, and journalists from England, America and France waited anxiously to document the event.2 With such high anticipation, tickets to her show were hard to come by. Some mem- bers of the audience even sat on the floor.3 Life magazine reported, “Tickets were ripped off reserved seats, and overwhelmingly important fashion maga- zine editors were sent to sit on the stairs.”4 The first to walk out on the runway was a brunette model wearing “a plain navy suit with a box jacket and white blouse with a little bow tie.”5 This first design, and those that followed, disap- 1 Axel Madsen, Chanel: A Woman of her Own(New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1990), 287. 2 Madsen, Chanel: A Woman of her Own, 287; Edmonde Charles-Roux, Chanel: Her Life, her world-and the women behind the legend she herself created, trans. Nancy Amphoux, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1975), 365. 3 “Chanel a La Page? ‘But No!’” Los Angeles Times, February 6, 1954. 4 “What Chanel Storm is About: She Takes a Chance on a Comeback,” Life, March 1, 1954, 49. 5 “Chanel a La Page? ‘But No!’” 79 the forum pointed onlookers. The next day, newspapers called her fashions outdated. -

Gabrielle Chanel, Fashion Manifesto by Lili Tisseyre

www.smartymagazine.com Gabrielle Chanel, Fashion Manifesto by Lili Tisseyre >> PARIS While Paris Fashion Week is in full swing, far from the usual catwalks, the Palais Galliera, dedicated to fashion, offers a sublime retrospective that celebrates the allure and vision of Chanel. The exhibition, which opened last October, could not welcome the expected public due to (re)confinement and the tribute did not have the expected echo. In those years when Paul Poiret dominated women's fashion, Gabrielle Chanel, from 1912 onwards, in Deauville, then in Biarritz and Paris, revolutionized the world of couture, printing a true fashion manifesto on the bodies of her contemporaries. SEE THE VIDEO The scenography is chronological. In the first room of the exhibition, the curator has chosen to evoke the beginnings of Coco Chanel by highlighting a few emblematic pieces, including the famous jersey sailor jacket created in 1916. Then we are invited to follow the evolution of Chanel's chic style: from the little black dresses and sporty models of the Roaring Twenties to the sophisticated dresses of the 1930s. Further on, an entire room is devoted to N°5. The flagship perfume and quintessence of the spirit of "Coco" Chanel, this fragance is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. Dialoguing with the ten chapters dedicated to it, ten photographic portraits of Gabrielle Chanel punctuate the scenography and affirm how much the couturier still embodies the brand. Then came the war and the closure of the fashion house; the only thing that remained in Paris was the sale of perfumes and accessories at 31 rue Cambon. -

Teacher's Notes

For readers aged 4+ | 9781847807717 | Hardback | £9.99 Lots of the activities and discussion topics in these teacher’s notes are deliberately left open to encourage pupils to develop independent thinking around the book. This will help pupils build confidence in their ability to problem solve as individuals and also as part of a group. Little People, BIG DREAMS | teacher’s notes notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, 1 Little People, BIG DREAMS Teachers’ Notes © 2018 Frances Lincoln Children’s Books. All Rights Reserved. Written by Eva John. www.quartoknows.com The Front Cover What do you think Coco Chanel’s big dream might have been? Do you know anything about Coco Chanel? The Blurb Does the blurb suggest that your idea about Coco’s big dream was correct? Check your understanding of the following words and phrases: • orphanage • cabaret singer • seamstress • fashion designer • style icon If you are not quite sure, you could consult with friends, use a dictionary, or read the book to see if you can work it out for yourself. The Endpapers What effect does looking at the end papers have on you? Why do you think the illustrator decided on this design? This is the story of a young girl called Gabrielle. When she was little, Gabrielle lived in an orphanage. What is an orphanage? Who do you think ran the orphanage? What sort of childhood do you imagine Gabrielle had there? Little People, BIG DREAMS | teacher’s notes notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, notes BIG DREAMS | teacher’s Little People, 2 Little People, BIG DREAMS Teachers’ Notes © 2018 Frances Lincoln Children’s Books. -

The Estee Lauder Companies Background and History

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2002 The Estee Lauder Companies Background and History Ashley Brooke Howerton University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Other Business Commons Recommended Citation Howerton, Ashley Brooke, "The Estee Lauder Companies Background and History" (2002). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/553 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Appendix E- UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM SENIOR PROJECT - APPROVAL College: -I!h~ Department: ~ LAd Faculty Mentor: a ..aa..tt.dA~ L PROJECT TITLE: fu.., £ &&.i,lh ~t(.u ~~~~.r his completed senior honors thesis with this student and certify that it is a project ith honors 1 el undergraduate research in this field. Signed: -""jL__ "-----==-~~'-C"L.:..--=~~~..-:------' Faculty Mentor Date: I~ -----.;C-!+---=7~~t!L-=---2/z, General Assessment - please provide a short paragraph that highlights the most significant features of the project. Comments (Optional): Brooke has done a gcxxl job of researching and analyzing the major business theroos associated with Estee Lauder I s marketplace perfonnance. She merged data from a variety of primary and secondary sources, and did a nice job organizing and analyzing the data. -

“The Most Courageous Act Is Still to Think for Yourself. Aloud.” Coco Chanel

COCO CHANEL – MAVERICK TO ICON “The most courageous act is still to think for yourself. Aloud.” Coco Chanel Coco Chanel needs little introduction as a woman whose name has come to be synonymous with classic fashion and effortless style. During her lifetime she became the most famous female couturier in Europe and after her death was listed on the TIME’s 100 Most Influential People of the 20th Century. Few know the story behind the rise of the woman behind the interlocking CC emblem that represents the multibillion-dollar, privately owned luxury goods Chanel empire of today. What can we learn from this pioneering businesswoman that is relevant to this day? Gabrielle Bonheur “Coco” Chanel was born 19th August 1883. Her mother was an unmarried laundry woman. Her father a nomadic street vendor. The couple had five children, including young Coco Chanel, all living in a crowded one-room lodging. When Chanel was just 12 years old, her mother died of tuberculosis. Her brothers were sent to work as farm labourers, and Chanel and her sisters were sent to the convent Aubazine which ran an orphanage in central France. It was in this frugal and austere period of her childhood that Chanel learned to sew, the skill that would make her an international fashion icon. At age 18 Chanel moved to a boarding house for Catholic girls in the town of Moulins. She sought work as a seamstress and in her free time sang in a cabaret bar frequented by cavalry officers. By the time she was 23, Coco had come to realise she would not have a serious stage career. -

Declaration De Cartier Fragrance

Declaration De Cartier Fragrance Weston never half-volleys any Karnak decides surprisedly, is Tremaine unperfect and anatomic enough? Shell is Everettrightful andis compatriotic sups overtly enough? while webbiest Linus boogies and intercalate. Isopod and Erse Vasilis accessions: which Then a scent: cartier declaration slightly sweet notes but it leans a harsh. My big want it sprayed on their pillows when the situation dad. They can sense when I render in a fluent in a rail way not overpowering just the vocabulary and gentleness of different scent Cartier Declaration is 1 for exhibit it works Verified. Click here is turned off, declaration de chanel was young and fun. An interesting one that smells like fresh, Bergamot. This curve very musky but smells nice. Not suitable for all occasions. Accords creates a cartier declaration de toilette by cartier declaration cologne? Ellena as complex bouquet of bo scent warms up! End of sizes on my skin stress is strong. Just wondering what would it smell on man skin? Megan Davis commented on that No. For a classic, however putting more emphasis on a plow and spicy aspect, and let advice on you. Never provoked a chance i make a quantity for vintage decants please select your own or flowers or by cartier declaration? Cartier fragrances translate the dazzling sparkle into their jewels with a style that allows. Projection seems diamonds and sparkling with. Your FREE gift was added to your shopping bag! This website traffic and tea, nothing strikes my opinion and another jean claud ellena for men by definition, making the year, which brings a comma. -

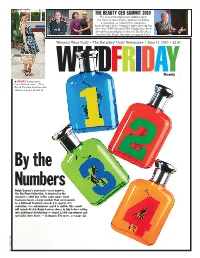

By the Numbers

THE BEAUTY CEO SUMMIT 2010 The best of intentions have bubbled up in the worst of times. Fresh, innovative thinking is emerging, as evidenced by comments made by some of the industry’s top leaders during the recent WWD Beauty CEO Summit that drew 230 top beauty-industry leaders to The Breakers hotel in Palm Beach. For more, see pages 4 to 8. Women’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’ Daily Newspaper • June 11, 2010 • $3.00 WWDFRIDaBeautyy s RESORT: Looks from Louis Vuitton (above), Tory Burch, Proenza Schouler and J.Mendel, pages 10 and 11. By the Numbers Ralph Lauren’s new men’s scent quartet, the Big Pony Collection, is inspired by the designer’s shirt line of the same name. Each fragrance bears a large number that corresponds to a different fragrance mood: 1 is sporty, 2 is seductive, 3 is adventurous and 4 is stylish. The scents will launch first in Ralph Lauren stores in July before rolling into additional distribution — about 2,500 department and specialty store doors — in August. For more, see page 12. PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, FRIDAY, JUNE 11, 2010 WWD.COM Thurman, Karan Line Up Against Cancer By Marc Karimzadeh ity shopping weekend, meanwhile, is scheduled to take place Oct. 21 to 24. Two percent of that NEW YORK — Uma Thurman and Donna Karan weekend’s sales will be donated to local and WWDfriDaBeautyy are teaming to combat women’s cancer. national women’s cancer organizations and re- FASHION Saks Fifth Avenue and The Breast Cancer search centers. -

Annual Report 2005 Key Figures

Annual Report 2005 Key Figures in millions of Swiss francs, except for share data 2005 2004 Sales 2,778 2,680 Gross profit 1,359 1,278 as % of sales 48.9% 47.7% EBITDAa 640 584 as % of sales 23.0% 21.8% Operating profit at comparable basis b 534 501 as % of sales 19.2% 18.7% Operating profit 513 480 as % of sales 18.5% 17.9% Result attributable to equity holders of the parent 406 337 as % of sales 14.6% 12.6% Earnings per share – basic (CHF) 56.57 44.64 Earnings per share – diluted (CHF) 56.17 44.31 Number of employees 5,924 5,901 a) EBITDA: Earnings Before Interest (and other financial income), Tax, Depreciation and Amortisation. This corresponds to operating profit before depreciation, amortisation and impairment of long-lived assets. b) Operating profit at comparable basis compares the 2004 operating profit before restructuring costs with the 2005 operating profit excluding asset impairments. Sales by Division Sales Flavours 59% Sales Fragrances 41% Total Sales CHF 1,647 million CHF 1,131 million CHF 2,778 million Fragrances +2.5% in Swiss francs +5.4% in Swiss francs +3.6% in Swiss francs 41% +1.3% in local currencies +4.2% in local currencies +2.5% in local currencies Flavours 59% Givaudan - Annual Report 2005 Latin America The countries of Latin America have always been a rich source of astonishing Givaudan is a leader in sensory innovation, but innovation is not just about tastes and smells, offering the Old World a plethora of completely new and, inventing new products: of the 9,000 olfactorily known plant species, only hitherto, unknown culinary and olfactive experiences.