Introduction the Language of Happiness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

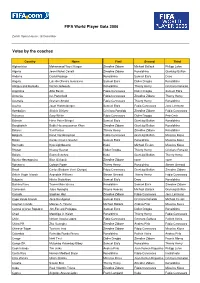

Votes by the Coaches FIFA World Player Gala 2006

FIFA World Player Gala 2006 Zurich Opera House, 18 December Votes by the coaches Country Name First Second Third Afghanistan Mohammad Yousf Kargar Zinedine Zidane Michael Ballack Philipp Lahm Algeria Jean-Michel Cavalli Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Gianluigi Buffon Andorra David Rodrigo Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Deco Angola Luis de Oliveira Gonçalves Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Ronaldinho Antigua and Barbuda Derrick Edwards Ronaldinho Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Argentina Alfio Basile Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Samuel Eto'o Armenia Ian Porterfield Fabio Cannavaro Zinedine Zidane Thierry Henry Australia Graham Arnold Fabio Cannavaro Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Austria Josef Hickersberger Samuel Eto'o Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Azerbaijan Shahin Diniyev Cristiano Ronaldo Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Bahamas Gary White Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Petr Cech Bahrain Hans-Peter Briegel Samuel Eto'o Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Bangladesh Bablu Hasanuzzaman Khan Zinedine Zidane Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Belarus Yuri Puntus Thierry Henry Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Belgium René Vandereycken Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Miroslav Klose Belize Carlos Charlie Slusher Samuel Eto'o Ronaldinho Miroslav Klose Bermuda Kyle Lightbourne Kaká Michael Essien Miroslav Klose Bhutan Kharey Basnet Didier Drogba Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Bolivia Erwin Sanchez Kaká Gianluigi Buffon Thierry Henry Bosnia-Herzegovina Blaz Sliskovic Zinedine Zidane none none Botswana Colwyn Rowe Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Steven Gerrard Brazil Carlos Bledorin Verri (Dunga) Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Zinedine Zidane British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Steven Gerrard Thierry Henry Fabio Cannavaro Bulgaria Hristo Stoitchkov Samuel Eto'o Deco Ronaldinho Burkina Faso Traore Malo Idrissa Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Zinedine Zidane Cameroon Jules Nyongha Wayne Rooney Michael Ballack Gianluigi Buffon Canada Stephen Hart Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Cape Verde Islands José Rui Aguiaz Samuel Eto'o Cristiano Ronaldo Michael Essien Cayman Islands Marcos A. -

Economic, Social and Cultural Challenges

Transition1.Qrk 28/2/05 3:51 pm Page 1 Majumdar &Saad This book deals with Margaret A. Majumdar MARGARET A. MAJUMDAR & MOHAMMED SAAD the economic and is Professor of Francophone developmental challenges Studies at the University of facing contemporary Portsmouth. Algerian society. The social structures, the Mohammed Saad is Reader political institutions, the in Innovation and Operations movements and Management and Head of ideologies, as well as the School of Operations and Transition & cultural dilemmas, are Information Management at considered in depth to the University of the West of give the fullest picture of England, Bristol. the twenty-first century development. &DevelopmentinAlgeria Transition Development The contributors represent a range of expertise in economics, business management, sociology, linguistics, in Algeria political science and cultural studies. Their diverse backgrounds and Economic, Social and Cultural Challenges perspectives permit this publication to explore new avenues of debate, which represent a significant contribution to the understanding of the present problems and potential solutions. intellect ISBN 1-84150-074-7 intellect PO Box 862 Bristol BS99 1DE United Kingdom www.intellectbooks.com 9 781841 500744 TransitionLayout 28/2/05 3:34 pm Page i TRANSITION AND DEVELOPMENT IN ALGERIA: ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES Edited by Margaret A. Majumdar and Mohammed Saad TransitionLayout 28/2/05 3:34 pm Page ii First Published in the UK in 2005 by Intellect Books, PO Box 862, Bristol BS99 1DE, UK. First Published in the USA in 2005 by Intellect Books, ISBS, 920 NE 58th Ave. Suite 300, Portland, Oregon 97213-3786, USA. Copyright ©2005 Intellect Ltd. All rights reserved. -

Raymond Kopa: El Fallido Relevo De Di Stéfano

Cuadernos de Fútbol Revista de CIHEFE https://www.cihefe.es/cuadernosdefutbol Raymond Kopa: El fallido relevo de Di Stéfano Autor: José Ignacio Corcuera Cuadernos de fútbol, nº 86, abril 2017. ISSN: 1989-6379 Fecha de recepción: 05-03-2017, Fecha de aceptación: 17-03-2017. URL: https://www.cihefe.es/cuadernosdefutbol/2017/04/raymond-kopa-el-fallido-relevo-de-di- stefano/ Resumen Artículo biográfico sobre Raymond Kopa, el “Napoleón del fútbol”, como homenaje tras su reciente fallecimiento. Palabras clave: Balón de oro, Copa de Europa, fichajes, fútbol español, historia, Kopa, Luis Guijarro, Real MadridStade Reims Abstract Keywords:Luis Guijarro, Stade Reims, Real Madrid, Kopa, European Cup, History, Spanish Football, Golden Ball, Signings Biographical article about Raymond Kopa, the ‘Napoleon of football’, as a tribute after his recent death. Date : 1 abril 2017 1 / 17 Cuadernos de Fútbol Revista de CIHEFE https://www.cihefe.es/cuadernosdefutbol El 3 de marzo último falleció Raymond Kopa, buen futbolista, conforme pudo acreditar en el Stade Reims, y sólo con cuentagotas durante sus tres años en un Real Madrid que apabullaba. Por no variar, las necrológicas urdidas a toda prisa, reproduciendo casi al dictado notas de agencia igualmente apresuradas, sabían a poco. Alguna de ellas, además, se excedía en loas al futbolista, sin dedicar un párrafo a la persona, a su despedida de nuestro Campeonato, capitidisminuido y hasta deglutiendo cierto poso de decepción. Buenas razones para acercarnos al personaje, máxime cuando hoy su nombre, como el de tantas otras estrellas envejecidas, semejará nebulosa recóndita para muchos. Hijo de mineros polacos instalados en Francia, y minero a su vez hasta que lo redimiese el fútbol, Raymond Kopaszewski Wlodzarczyck vino al mundo en Noeux-Les-Mines, el 13 de octubre de 1931. -

703 Prelims.P65

Football in France Global Sport Cultures Eds Gary Armstrong, Brunel University, Richard Giulianotti, University of Aberdeen, and David Andrews, The University of Maryland From the Olympics and the World Cup to extreme sports and kabaddi, the social significance of sport at both global and local levels has become increasingly clear in recent years. The contested nature of identity is widely addressed in the social sciences, but sport as a particularly revealing site of such contestation, in both industrialising and post-industrial nations, has been less fruitfully explored. Further, sport and sporting corporations are increasingly powerful players in the world economy. Sport is now central to the social and technological development of mass media, notably in telecommunications and digital television. It is also a crucial medium through which specific populations and political elites communicate and interact with each other on a global stage. Berg publishers are pleased to announce a new book series that will examine and evaluate the role of sport in the contemporary world. Truly global in scope, the series seeks to adopt a grounded, constructively critical stance towards prior work within sport studies and to answer such questions as: • How are sports experienced and practised at the everyday level within local settings? • How do specific cultures construct and negotiate forms of social stratification (such as gender, class, ethnicity) within sporting contexts? • What is the impact of mediation and corporate globalisation upon local sports cultures? Determinedly interdisciplinary, the series will nevertheless privilege anthropological, historical and sociological approaches, but will consider submissions from cultural studies, economics, geography, human kinetics, international relations, law, philosophy and political science. -

DIAMBARS SOUTH AFRICA Author: D. Habchi OVERVIEW Update

DIAMBARS SOUTH AFRICA Author: D. Habchi OVERVIEW Update: 01/02/10 I. ABOUT DIAMBARS Diambars is a non-governmental organization, created in 2000 by renowned football players, viz., 1998 world champions Patrick Vieira and Bernard Lama, and Jimmy Adjovi-Boco (former captain of the Benin National Team), with the support of several other champions and soccer legends. Diambars uses football as a driving force for education and offers disadvantaged children in Africa, with a talent for playing football, the opportunity to acquire solid academic training. Diambars has created a sport-education model that provides: ― Top level sport-education institutes, which offer accommodation, education and physical training to children between the ages of 13 and 18; the students are expected to achieve high standards in football and education, ― Community-based social development programs, using the power of football as an effective tool to promote education at large. Through education and top level sports, the Diambars Institute aims to favor the integration and fair social development of young people who have chosen high-level sports as a means of self- achievement, without suffering by being uprooted from their home environment. Diambars also acts at the level of sustainable development in response to the lack of educational structures and the poor level of sport in Africa. The model was properly endorsed by UNESCO which recognized Diambars’ capacity to provide quality education and promote the social role of sport. Diambars is a Senegalese word for fighters, which is very fitting for a football academy concept also designed to address the plight of African football players who generally choose the world of football at the expense of education. -

Sport and Discrimination

Sport and discrimination: the media perspective The texts of this publication have been written by Virginie Sassoon on the request of the Speak out against discrimination Campaign secretariat of the Council of Europe. The various articles published here are extracted from the results of the Sport and Discrimination: the media perspective seminar. The opinions expressed in this publication should not be regarded as plac- ing upon the legal instruments mentioned in it any official interpretation capable of binding the governments of member states, the Council of Europe’s statutory organs or any organ set up by virtue of the European Convention on Human Rights. Contents Introduction ...................................................................................... 5 The Council of Europe, Intercultural dialogue and Sport in Europe ... 7 Football in the media spotlight .................................................... 9 Identity issues: everyday racism and the stadium as a place for letting off steam .................................................................. 11 Regionalism, nationalism … and Europe? .................................... 13 Sport as an entertainment industry. Sports media under the influence of business ................................ 15 Lilian Thuram launches his foundation ‘Education against racism‘ ... 19 Sexist sport ............................................................................... 21 Combating racism in football. The FARE network’s experience .................................................. -

“Preocupado Mesmo Eu Estou Com O Le Pen”!

POLÍTICA X COPA DO MUNDO: “PREOCUPADO MESMO EU ESTOU COM O LE PEN”! Marcos Emílio Ekman Faber Em 2006, o ultraconservador Jean-Marie Le Pen, candidato à presidência da República na França pela Frente Nacional, apareceu com um discurso onde defendia uma França dos franceses, ou seja, sem negros, sem orientais, sem árabes e sem estrangeiros. Le Pen defendia uma França nascida da aliança entre Clóvis, rei dos Francos, e a Igreja Católica Apostólica Romana. Para ele, ser francês é descender desta aliança, portanto, Le Pen defendia que os “novos franceses”, principalmente imigrantes das ex- colônias não deveriam ter acesso à cidadania francesa. Neste mesmo ano, aconteceu a Copa do Mundo da Alemanha. Como sempre, existia muita esperança de que a seleção brasileira vencesse essa copa. Na verdade, para a grande maioria da crítica brasileira, havia a certeza de que o Brasil seria o campeão. Alguns críticos chegavam a apontar àquela seleção como a maior desde o escrete de 1970. Chegaram a comparar Ronaldinho Gaúcho a Pelé. O “quarteto mágico” formado por Kaká, Ronaldinho Gaúcho, Adriano ‘Imperador’ e Ronaldo ‘Fenômeno’ era apontado como imbatível. Alguns exaltados chegavam a defender um “quinteto mágico” com o acréscimo de Robinho. Esses críticos esqueciam que futebol, como tudo na vida, necessita de equilíbrio, portanto, faltavam volantes àquela seleção. Deu no que deu! A seleção brasileira não jogou nenhuma partida bem, na verdade jogou muito mal em todos os jogos e acabou sendo eliminada pela França de Zinedine Zidane, Lilian Thuram e Thierry Henry. Como sempre se buscou um culpado para a derrota. Afinal, “o Brasil é tão superior aos demais que quando perde, perde para si mesmo”, se a frase não fosse absurda, seria cômica. -

Football De Légendes, Une Histoire Européenne

Éditions du sous-sol SORTIE 19/05/2016 FOOTBALL DE LÉGENDES, 30 joueurs 30 écrivains Une histoire 30 photos européenne Hors-série isbn : 978-2-36468-216-0 prix : 18 euros format : 170/240 mm cartonné collection : Desports hors-série pagination : 96 pages domaine : sport À l’occasion du Championnat d’Europe de football Sur une idée originale de que la France accueillera cet été, la revue Desports Pierre-Louis Basse : chausse les crampons pour un numéro hors-série en collaboration avec les Grands Événements Roberto Baggio par Roberto Saviano de l’Élysée et compose une feuille de match Franz Beckenbauer par Volker Schlöndorff inédite. Trente écrivains commentent trente George Best par John King photographies de trente joueurs qui ont bâti Oleg Blokhine par Andreï Kourkov la légende du football européen. Bobby Charlton par David Peace Johan Cruijff par Cees Nooteboom Alfredo Di Stéfano par Javier Marías Eusébio par Gonçalo Tavares Numéro hors-série en Ruud Gullit par Maylis de Kerangal Gheorge Hagi par Lola Lafon partenariat avec l’exposition Zlatan Ibrahimović par Enki Bilal “Football de légendes”, qui se Andrés Iniesta par Jean-Paul Dubois Kevin Keegan par Jonathan Coe tiendra sur les grilles de l’Hôtel Miroslav Klose par Hans-Ulrich Treichel de Ville de Paris du 9 mai Raymond Kopa par Philippe Delerm Stanley Matthews par François Bott au 10 juillet 2016. Éric Cantona par André Velter Antonín Panenka par Paul Fournel Michel Platini par Bernard Pivot Ferenc Puskás par Olivier Barrot Gianni Rivera par Erri De Luca Cristiano Ronaldo par Jean Rouaud Matthias Sindelar par Olivier Guez Hristo Stoitchkov par Julia Kristeva Marco Van Basten par Patrice Delbourg Paul Van Himst par Patrick Roegiers Fritz Walter par Alban Lefranc Xavi par Jean-Claude Michéa Lev Yachine par Bernard Chambaz Zinedine Zidane par Jean-Philippe Toussaint relations presse : relations librairies : Colombe Boncenne Estelle Roche Virginie Migeotte [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 06 83 06 07 11 06 75 87 28 20 06 77 78 58 44. -

Raymond Kopa, L'histoire D'une Légende De Passage À Nice

Raymond Kopa, l'histoire d'une légende de passage à Nice Extrait du Nice Premium http://www.nice-premium.com Raymond Kopa, l'histoire d'une légende de passage à Nice - Sports - Date de mise en ligne : lundi 27 octobre 2008 Nice Premium Copyright © Nice Premium Page 1/3 Raymond Kopa, l'histoire d'une légende de passage à Nice Imaginez un monde où un club domine l'Europe du foot. Imaginez un monde où un club domine la France du foot, et qu'il ne s'appelle pas l'Olympique Lyonnais mais le Stade de Reims. Imaginez un monde où l'un des meilleurs joueurs est Français. Seulement, il n'est pas fils de Kabyles mais d'origine polonaise. Ce monde semble impensable pour la plupart des gens. Pourtant il a existé. Il y a cinquante ans. Et celui qui faisait rêver la France ne s'appelait pas Zinedine Zidane mais Raymond Kopa. Mais l'un comme l'autre ont joué dans le club le plus titré d'Europe : le Real Madrid. L'équipe du Brésil de 1958 meilleure que celui de 1998. Cela pourrait prêter à sourire sauf quand celui qui le dit s'appelle Raymond Kopa. Et le palmarès plaide pour lui. Surtout lors de cette fabuleuse année 1958. Champion d'Espagne et vainqueur de la coupe d'Europe avec le Real Madrid, troisième de la Coupe du Monde en Suède, élu meilleur joueur du mondial, et surtout premier Ballon d'or " France Football " de l'histoire. C'est beaucoup pour un seul homme, mais peu pour celui qui deviendra l'une des légendes du football français. -

Football for Freedom! WH EN Football Becomes a CITIZEN SPORT! Eric Cantona Recounts the Story of Footballers That Have Resisted

MAKE YOUR VOTE MATTER! FOOTBALL FOR FREEDOM! WH EN FOOTBALL BECOMES A CITIZEN SPORT! ERIC CANTONA RECOUNTS THE STORY OF FOOTBALLERS THAT HAVE RESISTED. Telling the story of great players who I’m going to speak to you about real values, I’m going to speak to you about my football. became great men. The one I played, and the one I love – a football of solidarity, fraternity, and freedom. GILL ES ROF & GILLES PEREZ I’m going to speak to you about my football and why, in this world, we need it more than ever. Because, you see, still today we can change this world. ERIC CANTONA FOOTBALL REBELS - 5 X 26’ – 2012 – HD PRODUCED BY 13 PRODUCTIONS (CYRILLE PEREZ) - CANTO BROS PRODUCTIONS AND ARTE FRANCE AUTHORS/DIRECTORS: GILLES ROF AND GILLES PEREZ WITH THE PARTICIPATION OF ERIC CANTONA W hen football becomes a citizen sport! At a time when business seems to be corrupting our relationship with sport, the indomitable Eric Cantona shows us footballers who've managed to resist. Their names are Mekloufi, Sócrates, Pasic, Caszely, Drogba. 5 players who took part in disputes or fought back against the spheres of power, becoming figureheads of resistance or rebellion, well beyond their sole sporting achievements. A DOCUE M NTARY SERIES/MANIFESTO THAT REASSERTS THE VALUES OF SPORT AMONG CITIZENS, VIA 5 STORIES THAT ARE DEAR TO ERIC CANTONA. CASZELY MEKOI L UF AN D THE DEMISE AN D THE FLN TEAM OF ALLENDE (ALGERIA-FRANCE) (CHILE) R achid Mekhloufi was a player with the French football team, The Chilean player Carlos Caszely, close to Salvador Allende, who during the Algerian war, chose to go underground and rally was one of the rare top-calibre footballers to openly defy the his country to defend Algeria in 1958, in the FLN football team. -

Votes by the Captains FIFA World Player Gala 2006

FIFA World Player Gala 2006 Zurich Opera House, 18 December Votes by the captains Country Name First Second Third Afghanistan Maroof Gulistani Zinedine Zidane Franck Ribery Michael Ballack Algeria Gaouaoui Lounes Kaká Frank Lampard Zinedine Zidane Andorra Oscar Sonejee Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Fabio Cannavaro Angola Paulo Figueiredo Samuel Eto'o Ronaldinho Wayne Rooney Antigua and Barbuda Nathaniel Teon Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Alessandro Nesta Argentina Roberto Ayala Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Thierry Henry Armenia Sarigs Hovsepyan Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Samuel Eto'o Australia Lucas Neill Fabio Cannavaro Cristiano Ronaldo Thierry Henry Austria Andreas Ivanschitz Zinedine Zidane Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Azerbaijan Aslan Karimov Cristiano Ronaldo Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Bahamas Nesley Jean Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Michael Essien Bahrain Talal Jusuf Samuel Eto'o Gianluigi Buffon Jens Lehmann Bangladesh Huq Aminul Gianluigi Buffon Kaká Zinedine Zidane Belarus Sergey Shtaniuk Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Petr Cech Belgium no vote none none none Belize Vallan Dennis Symps Ronaldinho Thierry Henry Michael Essien Bermuda Kentione Jennings Samuel Eto'o Steven Gerrard Juan Roman Riquelme Bhutan Passang Tshering Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Miroslav Klose Bolivia Sergio Golarza Kaká Fabio Cannavaro Samuel Eto'o Bosnia-Herzegovina Zlatan Bajramovic Zinedine Zidane none none Botswana Modiri Carlos Marumo Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Michael Essien Brazil Lucimar da Silva Ferreira (Lucio) Didier Drogba Thierry Henry Gianluigi