Tell El-Amarna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fall Cooking Program 2016

FALL COOKING PROGRAM 2016 auroragov.org/cooking 1891 2016 AURORA, YEARS Welcome Dear Aurora Cooks Community! Hope you are enjoying this fall harvest time of year. We are gearing up for cooler weather and shorter days as we wind down our growing season. Check out all our garden-to-table classes and new series this session! We have The Preserved Pantry, the Frugal Chef and Scratch Baking Basics, as well as many family, kids and teen classes highlighting food from every corner of the world. If you are looking for something to do on a chilly evening, come to a cooking class date night! You can even come with a friend, or as a single. We have some exciting new couples cooking classes, including the Fleetwood Mac Tribute Dinner, complete with music during the class! Come jam out to some tunes and cook with us. See you soon in the kitchen! Katrina and the Aurora Cooks Team TABLE OF CONTENTS Parent/Tot Cooking 2 Parent/Family Cooking 4 Kids Cooking 6 Meadowood Cooking Classes 7 Preteen Cooking 8 Teen Cooking 9 Adult Cooking 15 and Older 11 Adult Cooking 21 and Older 17 Wine Tasting 19 Recipe of the Season 20 All classes will be held at Expo Recreation Center 10955 E. Exposition Ave. unless noted Meadowood Recreation Center • 3045 S. Laredo 1 parent/tot cooking Ages 3-6 with parent. Apple Fest Tiny Italian Pumpkin Treats $38 ($29 Resident) $38 ($29 Resident) $38 ($29 Resident) Celebrate the harvest season with your Create delicious meatballs & veggies your Learn to use pumpkin in lots of different tot! Menu: Apple Zucchini Muffin tot will feel proud they prepared themselves. -

Page-5 Local.Qxd

DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU MONDAY, MARCH 22, 2021 (PAGE 5) Expired injections case Headless Congress on brink MS, MOs, staff nurses of DH of collapse in J&K: Kavinder Excelsior Correspondent connecting more and more peo- Shopian fined for negligence ple with the party to ensure that Excelsior Correspondent diary," the order reads. JAMMU, Mar 21: Senior the entire J&K becomes a bas- It underlines that no action BJP leader and former Deputy tion of nationalist BJP and there- SRINAGAR, Mar 21: Days on part of the Medical Chief Minister, Kavinder Gupta fore every effort is to be made to after a 6 year-old-girl was Superintendent against the today said that Congress Party spread awareness of schemes given expired injections at negligent staff "speaks about has turned a spent force in J&K launched by PM Modi-led dis- BJP J&K President, Ravinder Raina addressing party leaders Ex-DyCM Tara Chand addressing workers meeting in Khour District Hospital Shopian, the with no significant face left in on Sunday. the negligence of the hospital pensation. He said with full con- meeting at Srinagar on Sunday. -Excelsior/Shakeel District Magistrate Shopian administration." the party to sail it out from the fidence that the next today imposed a fine on the "It is ordered that the offi- troubled waters. Government in J&K will be of Take message of PM to every People feeling cheated due to Medical Superintendent of the cers; Medical Superintendent The senior BJP leader while BJP which shall accelerate the hospital along with 2 doctors and Mohd Yaseen (MO), chairing BJP Working pace of development manifold nook, corner of Valley: Raina and several staff nurses. -

Bab Ii “Menarikan Sang Liyan” : Feminisme Dalam Industri Musik

BAB II “MENARIKAN SANG LIYAN”i: FEMINISME DALAM INDUSTRI MUSIK “A feminist approach means taking nothing for granted because the things we take for granted are usually those that were constructed from the most powerful point of view in the culture ...” ~ Gayle Austin ~ Bab II akan menguraikan bagaimana perkembangan feminisme, khususnya dalam industri musik populer yang terepresentasikan oleh media massa. Bab ini mempertimbangkan kriteria historical situatedness untuk mencermati bagaimana feminisme merupakan sebuah realitas kultural yang terbentuk dari berbagai nilai sosial, politik, kultural, ekonomi, etnis, dan gender. Nilai-nilai tersebut dalam prosesnya menghadirkan sebuah realitas feminisme dan menjadikan realitas tersebut tak terpisahkan dengan sejarah yang telah membentuknya. Proses historis ini ikut andil dalam perjalanan feminisme from silence to performance, seperti yang diistilahkan Kroløkke dan Sørensen (2006). Perempuan berjalan dari dalam diam hingga akhirnya ia memiliki kesempatan untuk hadir dalam performa. Namun dalam perjalanan performa ini perempuan membawa serta diri “yang lain” (Liyan) yang telah melekat sejak masa lalu. Salah satu perwujudan performa sang Liyan ini adalah industri musik populer K-Pop yang diperankan oleh perempuan Timur yang secara kultural memiliki persoalan feminisme yang berbeda dengan perempuan Barat. 75 76 K-Pop merupakan perjalanan yang sangat panjang, yang mengisahkan kompleksitas perempuan dalam relasinya dengan musik dan media massa sebagai ruang performa, namun terjebak dalam ideologi kapitalisme. Feminisme diuraikan sebagai sebuah perjalanan “menarikan sang Liyan” (dancing othering), yang memperlihatkan bagaimana identitas the Other (Liyan) yang melekat dalam tubuh perempuan [Timur] ditarikan dalam beragam performa music video (MV) yang dapat dengan mudah diakses melalui situs YouTube. Tarian merupakan sebuah bentuk konsumsi musik dan praktik kultural yang membawa banyak makna tersembunyi mengenai konteks sosial (Wall, 2003:188). -

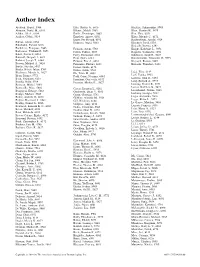

Author Index

Author Index Al-Abed, Yousef, 5904 Ellis, Shirley A., 6016 Khailaie, Sahamoddin, 5983 Altmann, Daniel M., 6041 Ellouze, Mehdi, 5863 Khan, Shaniya H., 5873 Ashkar, Ali A., 6184 Emilie, Dominique, 5863 Kim, Nina, 6031 Auffray, Ce´dric, 5914 Engelsen, Agnete, 6192 Kines, Rhonda C., 6172 Enger, Per Øyvind, 6192 Kirshenbaum, Arnold, 5924 Babian, Artem, 6184 Ezquerra, Angel, 5883 Klarquist, Jared, 6124 Babrzadeh, Farbod, 6016 Kmiecik, Justyna, 6192 Bachelerie, Franc¸oise, 5863 Fabisiak, Adam, 5763 Knight, Katherine L., 5951 Badovinac, Vladimir P., 5873 Fallon, Padraic, 6103 Koguchi, Yoshinobu, 5894 Baker, Steven F., 6031 Favry, Emmanuel, 6041 Kohlmeier, Jacob E., 5827 Bancroft, Gregory J., 6041 Feau, Sonia, 6124 Konstantinidis, Diamantis G., 5973 Barbieri, Joseph T., 6144 Feldsott, Eric A., 6031 Krzysiek, Roman, 5863 Beaven, Michael A., 5924 Fernandes, Philana, 6103 Kurosaki, Tomohiro, 6152 Bertho, Nicolas, 5883 Ferrari, Guido, 6172 Binder, Robert Julian, 5765 Fichna, Jakub, 5763 Lajqi, Trim, 6135 Blackman, Marcia A., 5827 Flo, Trude H., 6081 Lam, Tonika, 5933 Blom, Bianca, 5772 Fodil-Cornu, Nassima, 6061 Lambris, John D., 6161 Bock, Stephanie, 6135 Franchini, Genoveffa, 6172 Lang, Richard A., 5973 Bonilla, Nelly, 5914 Freeman, Michael L., 5827 Bonneau, Michel, 5883 Lanning, Dennis K., 5951 Lanzer, Kathleen G., 5827 Bonneville, Marc, 5816 Garcia, Brandon L., 6161 Lecardonnel, Je´roˆme, 5883 Bouguyon, Edwige, 5883 Geisbrecht, Brian V., 6161 Leclercq, Georges, 5997 Bourge, Mickael, 5883 Genin, Christian, 5781 Le´ger, Alexandra, 5816 Bowie, Andrew G., 6090 Gilfillan, Alasdair M., 5924 Legge, Kevin L., 5873 Boyton, Rosemary J., 6041 Gill, Navkiran, 6184 Le Gorrec, Madalen, 5816 Bradley, Daniel G., 6016 Gillgrass, Amy, 6184 Legoux, Franc¸ois, 5816 Bramwell, Kenneth K. -

Model Local School Wellness Policies on Physical Activity and Nutrition

Model Local School Wellness Policies on Physical Activity and Nutrition National Alliance for Nutrition and Activity (NANA) March 2005 Background In the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act of 2004, the U.S. Congress established a new requirement that all school districts with a federally-funded school meals program develop and implement wellness policies that address nutrition and physical activity by the start of the 2006-2007 school year [provide link to Section 204]. In response to requests for guidance on developing such policies, the National Alliance for Nutrition and Activity (NANA, see www.nanacoalition.org) convened a work group of more than 50 health, physical activity, nutrition, and education professionals from a variety of national and state organizations to develop a set of model policies for local school districts. The model nutrition and physical activity policies below meet the new federal requirement. This comprehensive set of model nutrition and physical activity policies1 is based on nutrition science, public health research, and existing practices from exemplary states and local school districts around the country. The NANA work group’s first priority was to promote children’s health and well-being. However, feasibility of policy implementation also was considered. Using the Model Policies School districts may choose to use the following model policies as written or revise them as needed to meet local needs and reflect community priorities. When developing wellness policies, school districts will need to take into account their unique circumstances, challenges, and opportunities. Among the factors to consider are socioeconomic status of the student body; school size; rural or urban location; and presence of immigrant, dual-language, or limited-English students. -

Resume & Song List

Skip Browner, Piano Player P.O. Box 1612 Hendersonville, TN 37077 T 615-478-0506 [email protected] www.skipbrowner.com PROFILE Dedicated and highly skilled in playing all styles, including jazz, rock, pop, blues, and country, with hundreds of songs in my repertoire. I have broad appeal and skill at connecting with a wide range of audiences. EXPERIENCE Piano Bar Entertainer: Woody’s Steak House, Angelo’s Bistro, Nana Rosa Italian Restaurant, Sand Trap at 12 Stones — 2009-2020 Along with being a piano bar entertainer, for the past 1 5 years, I have performed at numerous special events and private functions in and around the Nashville area. Pianist, band leader and arranger, Hot Pursuit, Hendersonville Tennessee — Seventeen years Formed my own band called Hot Pursuit. We played the Nashville and Southeast circuits for 17 years. This was a popular and highly sought after band. We played everything from Top 40 to rock and country. Staff Pianist, Music Village and Twitty City, Hendersonville Tennessee — Two years Played with the house band and accompanied the guest artists. Pianist, Tammy Wynette, Nashville Tennessee — Five years Played hundreds of venues around the world, from Carnegie Hall to The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, and performed for the President of the United States. Played on George Jones and Tammy Wynette’s recordings during that time. Pianist, Leroy Van Dyke, Nashville Tennessee — Four years Toured with Leroy and was the staff pianist and music director on his television show, “The Wonderful World of Country Music.” Pianist and arranger, JD Sumner and the Stamps, Nashville Tennessee — Two years Played with and wrote all of the orchestral arrangements for The Stamps. -

Wright Attacks Hypocrisy

ews Vol. LVII WELLESLEY COLLEGE NEWS;t WELLESLEY, MASS., APR. 9, 1964 No. 21 Variety Is Theme of "64 and the Arts"; Wright Attacks Hypocrisy Seniors Show Talents in Many Forms by Nancy Holler ' 66 equal rights, but no one is willing Variety is the most striking as- Barbara Betts have used oils. "Whether you like it or not to act on those beliefs. She asked pect of the poetry and art exhibits For variety, works in glass, wood, Mississippi is a part of you and the members of the audience how constituting "'64 and the Arts." ceramics and beads are also on you are a part of it" said Marion they would react when they were Summing up her selections for display. Sherry Fink is exhibiting Wright, NAACP defense lawyer, in suburban mothers and equal rights the "lesson in frankness" she gave involved letting a Negro family the program, Chairman Nana h~r collection of blown glass and here Monday night. live next door or having Negro Lampton said, "It's really amazing Kitty James her wood cuts. The "The issue in the South today children in school with theirs, per to see how exciting and different sculpture of Dudley Templeton is of free elections. There aren't haps even intermarrying. they can be. There's everything and ceramic and bead work of any." She asserted that Southern Miss Wright discussed the prob from very gifted poetry to blown Cia Bogate are also included. senators are elected by a handful lem of intermarriage stating that glass and woodcut projects." The poetry readings and art ex- of the electorate in their states. -

A School Leaders Guide to Collaboration and Community Engagement

A School Leaders Guide to Collaboration and Community Engagement This project was made possible by a grant from the Vitamin Cases Consumer Settlement Fund. Created as a result of an antitrust class action, one of the purposes of the Fund is to improve the health and nutrition of California consumers. A School Leader’s Guide to Collaboration and Community Engagement Produced by: California School Boards Association and Cities Counties Schools Partnership 2009 This project was made possible by a grant from the Vitamin Cases Consumer Settlement Fund. Created as a result of an antitrust class action, one of the purposes of the Fund is to improve the health and nutrition of California consumers. © 2009, California School Boards Association | 3100 Beacon Blvd., West Sacramento, CA 95691 800.266.3382 | www.csba.org | www.csba.org/wellness.aspx This material may not be reproduced or disseminated without prior written permission from the California School Boards Association. I CSBA 2009 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Paula Campbell, President Frank Pugh, President-elect Martha Fluor, Vice President Paul Chatman, Immediate Past President Scott P. Plotkin, Executive Director CALIFORNIA SCHOOL BOARDS ASSOCIATION PROJECT STAFF Martin Gonzalez, Deputy Executive Director Diane Greene, Principal Consultant Betsy McNeil, Student Wellness Consultant Katie Santos-Coy, Marketing Specialist Kerry Macklin, Senior Graphic Designer CITIES COUNTIES SCHOOLS PARTNERSHIP PROJECT STAFF Connie Busse, Executive Director Luan Burman Rivera, Director Special Projects Francesca Wright, Special Projects Consultant II BUILDING HEALTHY COMMUNITIES TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE _______________________________________ VII California School Boards Association VII Cities Counties Schools Partnership VIII Purpose of a Collaboration Guide X Acknowledgments XII 1. -

Diplomatic List – Fall 2018

United States Department of State Diplomatic List Fall 2018 Preface This publication contains the names of the members of the diplomatic staffs of all bilateral missions and delegations (herein after “missions”) and their spouses. Members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff of the mission having diplomatic rank. These persons, with the exception of those identified by asterisks, enjoy full immunity under provisions of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations. Pertinent provisions of the Convention include the following: Article 29 The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom, or dignity. Article 31 A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction of the receiving State. He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative jurisdiction, except in the case of: (a) a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the territory of the receiving State, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending State for the purposes of the mission; (b) an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved as an executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on behalf of the sending State; (c) an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside of his official functions. -- A diplomatic agent’s family members are entitled to the same immunities unless they are United States Nationals. -

Financial Conflicts of Interest Training Trainees Passed As of December 14, 2020

Financial Conflicts of Interest Training Trainees Passed as of December 14, 2020 Last Name First Name Date Passed Expiration Aakil Adam 7/15/2013 7/14/2017 Aalo Valerie 9/23/2020 9/22/2024 Abbas Bilal 12/11/2018 12/10/2022 Abbas Saleh 11/5/2015 11/4/2019 Abbas Diana, Saied 9/6/2016 9/5/2020 Abbott, MD Jodi F. 9/19/2015 9/18/2019 Abdalla Salma 7/7/2015 7/6/2019 Abdallah Sheila 3/18/2015 3/17/2019 Abdel‐Jelil Anissa 10/9/2019 10/8/2023 Abdennadher Belisle Myriam 4/3/2020 4/2/2024 Abdullah Ahmed 1/24/2020 1/23/2024 Abdullah, MD, MPH, PhD Abu Saleh 5/4/2017 5/3/2021 Abdurrahim Lukman 2/22/2017 2/21/2021 Abel Lois K. 3/4/2014 3/3/2018 Abi Hassan Abdul Samad Sahar, Chiquinquir 2/22/2018 2/21/2022 Ablavsky Edith T. 4/14/2013 4/13/2017 Abplanalp Samuel 3/13/2017 3/12/2021 Abraham, PhD Carmela R. 10/8/2015 10/7/2019 Abrams Jasmine 9/10/2019 9/9/2023 Abston Eric 10/2/2017 10/1/2021 Abur Defne 12/2/2019 12/1/2023 Achilike Confidence 5/20/2019 5/19/2023 Ackerbauer Kimberly 6/8/2020 6/7/2024 Acosta Alexander 1/21/2020 1/20/2024 Acuna‐Villaorduna, M.S., MD Carlos J. 4/11/2015 4/10/2019 Adams Chloe 9/7/2020 9/6/2024 Adams Bonnie 8/3/2017 8/2/2021 Adams, MD William G. -

Ewe (For Togo). Special Skills Handbook. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 255 040 FL 014 922 AUTHOR Kozelka, Paul R., Comp.; Agbovi, Yao Ete, Comp. TITLE Ewe (for Togo). Special Skills Handbook. Peace Corps Language Handbook Series. INSTITUTION Experiment in International-Living, Brattleboro, VT. SPONS AGENCY Peace Corps, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 80 CONTRACT PC-79-043-1034 NOTE 119p.; For related documents, see ED 203 708-709. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) -- Multilingual/Bilingual Materials (171) LANGUAGE Ewe; English EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS African Culture; African History; African Languages; Agriculture; Animal Husbandry; Daily Living Skills; Diseases; English; *Ewe; *Folk Culture; Health Services; Independent Study; Instructional Materials; Interpersonal Relationship; Language Skills; Letters (Correspondence); News Media; Proverbs; Religion; *Second Language Instruction; *Skill Development; *Sociocultural Patterns; *Vocabulary IDENTIFIERS Peace Corps; *Togo ABSTRACT A book of language and cultural material for teachers and students of Ewe presents vocabulary lists and samples of Ewe language in various contexts, including letters, essays, and newspaper articles. Although not presented in lesson format, the material can be adapted by teachers or used by students for independent study. It is divided into tko main parts. general skills and technical skills, with Ewe and English on facing pages. Contents of the general bkills section include these topics: proverbs, letter writing, sports, funeral ceremonies, traditional holidays and festivals, totems and taboos, divination, church, clothing, body parts, diseases and injuries, getting a motorbike repaired, foods, relationships between men and women, a history of the origins of the Ewe peoples, articles from Togo-Presse, Ewe folk tales, traditional songs, and traditions. -

Nana: V. 16 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NANA: V. 16 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ai Yazawa | 264 pages | 01 Jun 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421523750 | English | San Francisco, United States ENDOLIMAX NANA TRATAMIENTO PDF NANA News. Employee Spotlight. Fred S. Elvsaas Jr. Jameson Fisher Corporate Controller. Larry Snider Tax Manager. Facebook LinkedIn Instagram Twitter. Shareholder shareholderrelations nana. Business news nana. Today and every day, we recognize and honor all Al. Have you picked any cranberries this year? Auction: Brand new. Stock photo. Brand new: Lowest price The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. Buy It Now. Add to cart. Place bid. However, in the event of a dispute I will be the final arbitrator. See details - Nana: v. See all 6 brand new listings. About this product Product Information Nana Komatsu is a young woman who's endured an unending string of boyfriend problems. Moving to Tokyo, she's hoping to take control of her life and put all those messy misadventures behind her. She's looking for love and she's hoping to find it in the big city. Nana Osaki, on the other hand, is cool, confident and focused. She swaggers into town and proceeds to kick down the doors to Tokyo's underground punk scene. She's got a dream and won't give up until she becomes Japan's No. This is the story of two year-old women who share the same name. Even though they come from completely different backgrounds, they somehow meet and become best friends. The world of Nanais a world exploding with sex, music, fashion, gossip and all-night parties.