1+1 National Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Can Be Done to Protect Schools and Universities from Military Use?

QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ON THE DRAFT LUCENS GUIDELINES Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack GCPEA 1 GCPEA Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack What is military use of schools and universities? During armed conflicts, schools and universities are often used by armed forces and non-state armed groups as bases, barracks and temporary shelters, defensive and offensive positions or observation posts, weapons stores, and detention and interro - gation centres. Classrooms, school grounds, and lecture halls are also used for military training and to forcibly recruit children into armed groups. Sometimes schools and universities are taken over entirely, and students are pushed out completely. At other times education facilities are partially used for military purposes, with troops building a firing position on a school’s roof, or using a few classrooms, or occupying a playground while students continue to attend. Schools can be used for military purposes for a few days, months, or even years, and may be used during school hours, or when schools are not in session, over holidays, or in the evening. In all instances, military use of schools and universities puts students, teachers, and academics at risk. Where is military use of schools and universities happening? According to the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA), between 2005 and 2014, national armed forces and non-state armed groups, multi-national forces, and even peacekeepers have used schools and universities in at least 25 countries during armed confict, including: Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Chad, Colombia, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of Congo, Georgia, India, Iraq, Israel/Palestine, Libya, Mali, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Uganda, Ukraine, and Yemen. -

The Impact of British Imperialism on the Landscape of Female Slavery in the Kano Palace, Northern Nigeria Author(S): Heidi J

International African Institute The Impact of British Imperialism on the Landscape of Female Slavery in the Kano Palace, Northern Nigeria Author(s): Heidi J. Nast Source: Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 64, No. 1 (1994), pp. 34-73 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the International African Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1161094 . Accessed: 25/10/2013 22:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and International African Institute are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 129.128.216.34 on Fri, 25 Oct 2013 22:54:39 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Africa 64 (1), 1994 THE IMPACT OF BRITISH IMPERIALISM ON THE LANDSCAPE OF FEMALE SLAVERY IN THE KANO PALACE, NORTHERN NIGERIA Heidi J. Nast INTRODUCTION State slavery was historically central to the stability and growth of individual emirates in the Sokoto caliphate of northern Nigeria, an area overlapping much of the linguistic sub-region known as Hausaland (Fig. 1). -

Download The

Nothing to declare: Why U.S. border agency’s vast stop and search powers undermine press freedom A special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists Nothing to declare: Why U.S. border agency’s vast stop and search powers undermine press freedom A special report by the Committee to Protect Journalists Founded in 1981, the Committee to Protect Journalists responds to attacks on the press worldwide. CPJ documents hundreds of cases every year and takes action on behalf of journalists and news organizations without regard to political ideology. To maintain its independence, CPJ accepts no government funding. CPJ is funded entirely by private contributions from individuals, foundations, and corporations. CHAIR HONORARY CHAIRMAN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Kathleen Carroll Terry Anderson Joel Simon DIRECTORS Mhamed Krichen Ahmed Rashid al-jazeera Stephen J. Adler David Remnick reuters Isaac Lee the new yorker Franz Allina Lara Logan Alan Rusbridger Amanda Bennett cbs news lady margaret hall, oxford Krishna Bharat Rebecca MacKinnon David Schlesinger Susan Chira Kati Marton Karen Amanda Toulon bloomberg news the new york times Michael Massing Darren Walker Anne Garrels Geraldine Fabrikant Metz ford foundation the new york times Cheryl Gould Jacob Weisberg Victor Navasky the slate group Jonathan Klein the nation getty images Jon Williams Clarence Page rté Jane Kramer chicago tribune the new yorker SENIOR ADVISORS Steven L. Isenberg Sandra Mims Rowe Andrew Alexander David Marash Paul E. Steiger propublica Christiane Amanpour Charles L. Overby cnn international freedom forum Brian Williams msnbc Tom Brokaw Norman Pearlstine nbc news Matthew Winkler Sheila Coronel Dan Rather bloomberg news columbia university axs tv school of journalism Gene Roberts James C. -

For Immediate Release. FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2011, 6-9 Pm

For Immediate Release. Please add this information to your listings. Thank you! O’BORN CONTEMPORARY presents: REVOLUTION, a solo exhibition, featuring photographs from the Egyptian revolution by ED OU OCTOBER 1 – NOVEMBER 5, 2011 www.oborncontemporary.com DATES: FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2011, 6-9 pm Exhibition Opening and Reception Show Continues to NOVEMBER 5, 2011 Artist will be in attendance. Saturday, October 1, 12-5 pm Informal artist tours & talks. LOCATION: 131 Ossington Avenue, Toronto. GALLERY HOURS: Tuesday – Saturday, 11 – 6 and by appointment. TELEPHONE: 416.413.9555 EXHIBITION STATEMENT: In January of 2011, Egyptians from all corners of the country erupted in mass protests, challenging the heavy-handed rule of President Hosni Mubarak. The entire world watched, as Egyptians fought to have their grievances heard using sticks, stones, shouts, cell phones, and computers. Over the course of eighteen days, protesters occupied Tahrir square, the symbolic heart of the revolution where Egyptians of all ages and parts of society could speak with one unified voice, demanding the ouster of the president. They debated politics, shared their testimonies, supported each other, and mapped out their hopes and dreams for their country. On February 11, President Mubarak resigned, ending thirty years of autocratic rule. As the euphoria and excitement dies down, Egyptians are beginning to question what they have actually achieved. They are asking themselves what they want to make of their new Egypt and how to reconcile with decades of mistrust of authority, corruption, and an economy in shambles. The difficult part arguably, is still to come. ABOUT THE ARTIST: Ed Ou (24) is a culturally ambiguous Canadian photojournalist who has been bouncing around the Middle East, former Soviet Union, Africa, and the Americas. -

United Arab Emirates (Uae)

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: United Arab Emirates, July 2007 COUNTRY PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES (UAE) July 2007 COUNTRY اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴّﺔ اﻟﻤﺘّﺤﺪة (Formal Name: United Arab Emirates (Al Imarat al Arabiyah al Muttahidah Dubai , أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ (The seven emirates, in order of size, are: Abu Dhabi (Abu Zaby .اﻹﻣﺎرات Al ,ﻋﺠﻤﺎن Ajman , أ مّ اﻟﻘﻴﻮﻳﻦ Umm al Qaywayn , اﻟﺸﺎرﻗﺔ (Sharjah (Ash Shariqah ,دﺑﻲّ (Dubayy) .رأس اﻟﺨﻴﻤﺔ and Ras al Khaymah ,اﻟﻔﺠﻴﺮة Fajayrah Short Form: UAE. اﻣﺮاﺗﻰ .(Term for Citizen(s): Emirati(s أﺑﻮ ﻇﺒﻲ .Capital: Abu Dhabi City Major Cities: Al Ayn, capital of the Eastern Region, and Madinat Zayid, capital of the Western Region, are located in Abu Dhabi Emirate, the largest and most populous emirate. Dubai City is located in Dubai Emirate, the second largest emirate. Sharjah City and Khawr Fakkan are the major cities of the third largest emirate—Sharjah. Independence: The United Kingdom announced in 1968 and reaffirmed in 1971 that it would end its treaty relationships with the seven Trucial Coast states, which had been under British protection since 1892. Following the termination of all existing treaties with Britain, on December 2, 1971, six of the seven sheikhdoms formed the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The seventh sheikhdom, Ras al Khaymah, joined the UAE in 1972. Public holidays: Public holidays other than New Year’s Day and UAE National Day are dependent on the Islamic calendar and vary from year to year. For 2007, the holidays are: New Year’s Day (January 1); Muharram, Islamic New Year (January 20); Mouloud, Birth of Muhammad (March 31); Accession of the Ruler of Abu Dhabi—observed only in Abu Dhabi (August 6); Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad (August 10); first day of Ramadan (September 13); Eid al Fitr, end of Ramadan (October 13); UAE National Day (December 2); Eid al Adha, Feast of the Sacrifice (December 20); and Christmas Day (December 25). -

Lebanon: Managing the Gathering Storm

LEBANON: MANAGING THE GATHERING STORM Middle East Report N°48 – 5 December 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. A SYSTEM BETWEEN OLD AND NEW.................................................................. 1 A. SETTING THE STAGE: THE ELECTORAL CONTEST..................................................................1 B. THE MEHLIS EFFECT.............................................................................................................5 II. SECTARIANISM AND INTERNATIONALISATION ............................................. 8 A. FROM SYRIAN TUTELAGE TO WESTERN UMBRELLA?............................................................8 B. SHIFTING ALLIANCES..........................................................................................................12 III. THE HIZBOLLAH QUESTION ................................................................................ 16 A. “A NEW PHASE OF CONFRONTATION” ................................................................................17 B. HIZBOLLAH AS THE SHIITE GUARDIAN?..............................................................................19 C. THE PARTY OF GOD TURNS PARTY OF GOVERNMENT.........................................................20 IV. CONCLUSION ............................................................................................................. 22 A. A BROAD INTERNATIONAL COALITION FOR A NARROW AGENDA .......................................22 B. A LEBANESE COURT ON FOREIGN -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 155 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 No. 6 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Tuesday, January 13, 2009, at 12:30 p.m. Senate MONDAY, JANUARY 12, 2009 The Senate met at 2 p.m. and was The legislative clerk read the fol- was represented in the Senate of the called to order by the Honorable JIM lowing letter: United States by a terrific man and a WEBB, a Senator from the Common- U.S. SENATE, great legislator, Wendell Ford. wealth of Virginia. PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, Senator Ford was known by all as a Washington, DC, January 12, 2009. moderate, deeply respected by both PRAYER To the Senate: sides of the aisle for putting progress The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, ahead of politics. Senator Ford, some of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby fered the following prayer: appoint the Honorable JIM WEBB, a Senator said, was not flashy. He did not seek Let us pray. from the Commonwealth of Virginia, to per- the limelight. He was quietly effective Almighty God, from whom, through form the duties of the Chair. and calmly deliberative. whom, and to whom all things exist, ROBERT C. BYRD, In 1991, Senator Ford was elected by shower Your blessings upon our Sen- President pro tempore. his colleagues to serve as Democratic ators. -

A Case Study of Hadejia Emirate, Nigeria (1906-1960)

COLONIALISM AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES: A CASE STUDY OF HADEJIA EMIRATE, NIGERIA (1906-1960) BY MOHAMMED ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED MAH/42421/141/DF A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF HIGHER DEGREES AND RESEARCH IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MAY, 2015 DECLARATION This is my original work and has not been presented for a Degree or any other academic award in any university or institution of learning. ~ Signature Date MOHAMMED ABDULLAHI MOHAMMED APPROVAL I confirm that the work in this dissertation proposal was done by the candidate under my supervision. Signiture Supervisor name Date Peter Ssekiswa DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my late mother may her soul rest in perfect peace and my humble brother Yusif Bashir Hekimi and my wife Rahana Mustathha and the entire fimily In ACKNOWLEDGEMENT lam indeed grateful to my supervisor Peter Ssekiswa , who tirelessly went through my work and inspired me to dig deeper in to the core of the m matter , His kind critism patience and understanding assrted me a great deal Special thanks go to Vice Chancellor prof P Kazinga also a historian for his courage and commitment , however special thanks goes to Dr Kayindu Vicent , the powerful head of department of education (COEDU ) for friendly and academic discourse at different time , the penalist of the viva accorded thanks for observation and scholarly advise , such as Dr SOFU , Dr Tamale , Dr Ijoma My friends Mustafa Ibrahim Garga -

Suddensuccession

SUDDEN SUCCESSION Examining the Impact of Abrupt Change in the Middle East SIMON HENDERSON KRISTIAN C. ULRICHSEN EDITORS MbZ and the Future Leadership of the United Arab Emirates IN PRACTICE, Sheikh Muhammad bin Zayed al-Nahyan, the crown prince of Abu Dhabi, is already the political leader of the United Arab Emirates, even though the federation’s president, and Abu Dhabi’s leader, is his elder half-brother Sheikh Khalifa. This study examines leadership in the UAE and what might happen if, for whatever reason, Sheikh Muham- mad, widely known as MbZ, does not become either the ruler of Abu Dhabi or president of the UAE. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ POLICY NOTE 65 ■ JULY 2019 SUDDEN SUCCESSION: UAE RAS AL-KHAIMAH UMM AL-QUWAIN AJMAN SHARJAH DUBAI FUJAIRAH ABU DHABI ©1995 Central Intelligence Agency. Used by permission of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin. Formation of the UAE moniker that persisted until 1853, when Britain and regional sheikhs signed the Treaty of Maritime Peace The UAE was created in November 1971 as a fed- in Perpetuity and subsequent accords that handed eration of six emirates—Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah, responsibility for conduct of the region’s foreign rela- Fujairah, Ajman, and Umm al-Quwain. A seventh— tions to Britain. When about a century later, in 1968, Ras al-Khaimah—joined in February 1972 (see table Britain withdrew its presence from areas east of the 1). The UAE’s two founding leaders were Sheikh Suez Canal, it initially proposed a confederation that Zayed bin Sultan al-Nahyan (1918–2004), the ruler would include today’s UAE as well as Qatar and of Abu Dhabi, and Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed al-Mak- Bahrain, but these latter two entities opted for com- toum (1912–90), the ruler of Dubai. -

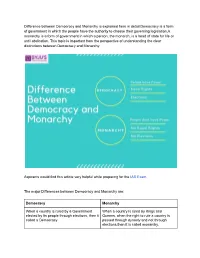

Difference Between Democracy and Monarchy Is Explained Here In

Difference between Democracy and Monarchy is explained here in detail.Democracy is a form of government in which the people have the authority to choose their governing legislation.A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is a head of state for life or until abdication. This topic is important from the perspective of understanding the clear distinctions between Democracy and Monarchy. Aspirants would find this article very helpful while preparing for the IAS Exam. The major Differences between Democracy and Monarchy are: Democracy Monarchy When a country is ruled by a Government When a country is ruled by Kings and elected by its people through elections, then it Queens, when the right to rule a country is called a Democracy passed through dynasty and not through elections,then it is called monarchy. The elected representatives makes the laws, The laws are framed by the Kings and rules and regulations on behalf of the people, Queens. People have no say in the for the welfare of the people formulation of laws. The elected representatives are held The Kings and Queens have no accountable by the people of the country. accountability. People do not have the power Hence elections are held and representatives to remove Kings and Queens from power if lose their right to rule, if they do not meet the they are dissatisfied with their rulings. expectations of the people People have the freedom to give their People do not have the right to condemn the feedback on policies, have the option to bring Monarchy. -

Kings for All Seasons

BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER ANALYSIS PAPER Number 8, September 2013 KINGS FOR ALL SEASONS: HOW THE MIDDLE EAST’S MONARCHIES SURVIVED THE ARAB SPRING F. GREGORY GAUSE, III B ROOKINGS The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publica- tion are solely those of its author(s) and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its scholars. Copyright © 2013 THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/about/centers/doha T A B LE OF C ON T EN T S I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................................1 II. Introduction ......................................................................................................................3 III. “Just Wait, They Will Fall” .............................................................................................5 IV. The Strange Case of Monarchical Stability .....................................................................8 Cultural Legitimacy ...................................................................................................8 Functional Superiority: Performance and Reform ..................................................12 -

The Taliban's Online Emirate

International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence ISSN: 0885-0607 (Print) 1521-0561 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ujic20 The Taliban’s Online Emirate Carl Anthony Wege To cite this article: Carl Anthony Wege (2017) The Taliban’s Online Emirate, International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 30:4, 833-837, DOI: 10.1080/08850607.2017.1337453 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08850607.2017.1337453 Published online: 07 Sep 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ujic20 Download by: [73.190.106.112] Date: 07 September 2017, At: 14:50 BOOKREVIEWS 833 The Taliban’s Online Emirate CARL ANTHONY WEGE Neil Krishan Aggarwal: The Taliban’s Virtual Emirate: The Culture and Psychology of an Online Militant Community Columbia University Press, New York, 2016, 211 p., $60. Neil Aggarwal, a Harvard- and of its distinct target audiences Yale-trained psychiatrist, has turned thereby increasing support for the his many talents to an analysis neo-Taliban insurgency. of The Taliban’s Virtual Emirate During the 1980s, foreshadowing emergent over the last decade. modern Taliban efforts in the cyber While a number of studies have been domain, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s published on al-Qaeda’s virtual Hizb-e Islami began publishing hard world and some on the Islamic State copy Islamist periodicals in Arabic, (ISIS), rather little is available on Pashto, Dari, Urdu, and English the Taliban’s cyber presence. Dr. during the Jihad against the Aggarwal utilizes his training in Soviets.