Entertaining the Classes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rod Blackmore's

Rod Blackmore’s AUSTRALASIAN THEATRE ORGANS New South Wales section Best known location: Penn Hughes residence Bexley Composite Christie/WurliTzer theatre organ 2 manuals (later 4 manuals) 16 ranks now substantially incorporated into the Capri theatre 4/29 theatre organ, Goodwood, Adelaide, South Australia Jack Penn Hughes originated from South Australia and was a professional theatre organist throughout the 1930s- 1940s until the late 1950s featuring at many organs reviewed in this series, particularly in Sydney but also in New Zealand. He was also known as the “singing organist”. His last theatre residence was at the Plaza theatre, Sydney. Despite his musical talents, many found him to be personally irascible, and in his dealings with redundant theatre organs he bordered on the unconscionable. In all some 12 organs were acquired by him and sold on to others, it being claimed that the purchasers did not always receive the organs they expected, Hughes having retained the best features for himself. He has also been identified in the late 1930s with involvement in the installation of instruments in theatres, eg the Astra theatre, Parramatta, and the Astra theatre, Drummoyne. In about 1957 Hughes bought the 2/10 Christie organ from the Empire (later St. James) theatre, Dunedin, New Zealand, and in 1959 he acquired the 2/8 WurliTzer organ (opus #748) previously in the Plaza theatre, Sydney. These two organs formed the basis of his residence organ, initially utilising the Empire Christie console. Later, Hughes acquired the 4 manual secondary console previously installed with the WurliTzer organ (opus #1987) of the State theatre, Melbourne, Victoria, and connected it to his residence organ. -

2019 Acp Bulletin

The Society of AUSTRALIAN CINEMA PIONEERS BULLETIN NOVEMBER 2019 IN THIS ISSUE: FROM THE PRESIDENT • Messages from the President and the individual liability from Directors and all Society President-Elect members, and the Society now has an ACN, making it easier to do business with our suppliers and key supporters. However the change does • State Presidents not affect the basically informal way the Society runs. • National Cinema Pioneer The only formal change is that the Society of the Year now has a Constitution which, together with any applicable ASIC regulations, defines the • State Pioneers of the Year Society’s objects and sets out its rules. The Constitution is accessible via the Society’s • Our generous donors website and Facebook pages. The website link is: https://www.cinemapioneers.com.au/wp-content/ uploads/2019/10/TSOACP-Ltd-Constitution- • Society contacts and FINAL-with-Schedules-1-and-2-300818-MU.pdf information As previously, the Society is governed and • Notice of Inaugural managed by its Directors who serve on the National Executive Committee chaired by the Annual General Meeting National President. Additionally, each State Branch (two of which incorporate the Territories) • Dates for State functions has a President and committee. • The Cinema ID Card & TIM READ The National Executive Committee consists of NATIONAL PRESIDENT the National President, the National President how to use it Elect, the 6 State Branch Presidents, up to 10 Incorporation Process Finalised former National Presidents and any elected • New Members additional directors. I wrote in this column last year that Sandra And, there is now an Annual General Meeting • In Memoriam Alexander, our National Secretary Treasurer would be lodging an application with ASIC for members which this year is being held for the Society to become incorporated as a on 28 November 2019 in Sydney. -

Broadcast List – HOT PIPES HALF HOUR 055 Page 1 Seq Artist Name Duration/Year Show Date Num Album Comments

Broadcast List – HOT PIPES HALF HOUR 055 Page 1 Seq Artist Name Duration/Year Show Date Num Album Comments 1 Jelani Eddington Good News 00:02:28 6-09-12 055 Symphonic Art 3/31 Wurlitzer+, Saunders Residence 2011 2 Barry Baker I Was A Fool 00:04:14 6-09-12 055 A Barry Baker Concert 4/36 Wurlitzer, Ronald Wehmeier Residence, Cincinnati, OH 1999 3 Lyn Larsen Manana 00:01:55 6-09-12 055 Good News Organ Stop Pizza, Mesa AZ - Wurlitzer 4/78 2000 4 Howard Beaumont Little Serenade 00:03:34 6-09-12 055 Ossett Town Hall Concert 3-13 Compton-Christie, Ossett Town Hall, West Yorkshire 2009 5 Reginald Dixon Love Makes The World Go Round; 00:02:52 6-09-12 055 At The Blackpool Tower Change Partners [Flapper CD] 1938 6 Bille Nalle I Write The Songs 00:05:20 6-09-12 055 The WTO Billy Project, Volume In concert May 27, 1978; Century II 1 Center Wurlitzer, Wichita, KS (ex NY 1978 Paramount) 7 Bryan Rodwell At The Jazz Band Ball 00:03:04 6-09-12 055 Organ Magic [ATOTC 3/8 Compton A175 4/2/33, Capitol Cassette 1] Cinema, Aberdeen 1989 8 Chris McPhee Aquarium 00:02:25 6-09-12 055 Celebrate 4/29 Hybrid, Capri Theatre, Goodwood, Adelaide, South Australia 2007 Broadcast List – HOT PIPES HALF HOUR 055 Page 2 Seq Artist Name Duration/Year Show Date Num Album Comments 9 George Wright By the Beautiful Sea 00:01:54 6-09-12 055 Volume 3 - The Genius of George Wright 1958 10 Vic Hammett Where Flamingoes Fly 00:04:19 6-09-12 055 The Very Thought Of You 4-19 Compton Noterman, Dreamland [Crystal Stereo LP] Cinema, Margate; (8 Compton 11 Noterman) Installed 1935 11 Scott Foppiano Betty Boop Theme 00:01:42 6-09-12 055 Renaissance 4/27 Robert Morton - Arlington Theatre, Santa Barbara; ex 1929 1996 Loew's Jersey Theatre, Jersey City (4/23) 12 John Giacchi Theme from Blue Hills 00:04:36 6-09-12 055 Journey Into Melody 4/29 Hybrid, Capri Theatre, Goodwood, SA 2000 13 Johnny Seng La Danza 00:01:55 6-09-12 055 Johnny [Concert Recording 4/19 Wurlitzer, St. -

Two ~..-Eat ~Arnei in the Theatr-E Or-Aan Wor-Ld with Your Help, the Legend and the Organ Will Go on Forever!

Two ~..-eat ~arnei in the Theatr-e Or-aan Wor-ld With your help, the legend and the organ will go on forever! \\\11 11 .... ~ ,,,,\ nt - 1111111,Jfl'II ~ --- JESSECRAWFORD CHICAGO THEATREWURLITZER CONSOLE Since 1977 CATOE,with the help of the American Theatre Organ Society has been workingto save one of the mostfamous theatre pipe organs - At last we can truly say the Chicago Theatre is secure. Frankly speaking, CATOE needs your help! We want to The building is now owned by a group of people who do the Chicago Theatre Wurlitzer restoration absolutely understand its historical significance as well as the need as complete and perfectly as is possible. Your contribu tor preserving all of its entertainment capabili ties. CA TOE tions of funds to help raise the thousands of dollars neces and ATOS have played a major role in the success of the sary can help secure, tor you and tor ATOS, a place and campaign . an instrument of unparalled historical and musical impor It is no secret that the Chicago Theatre Wurlitzer is in tance . We feel confident that our "taking care of our need of a complete and thorough restoration . Now that own" in the course of the Chicago Theatre restoration will the future of the theatre is secured, that work can begin . insure that ATOS will always be welcomed there to enjoy As a first step CA TOE has made a firm agreement with the this magnificent instrument. new owner of the Chicago to insure that the Wurlitzer will Contributions to CATOE tor the Chicago Theatre Wurlit play a role in that future of the building and that CA TOE zer restoration fund are totally tax deductible and a// of will oversee the restoration and the maintenance of the the funds you designate tor that project will be spent en instrument. -

I051 Companion Card Affiliate List 07 2021

South Australia South Australia Companion Card Affiliates List Updated July 2021 Page 1 of 42 APC I051 | July 2021 South Australia Table of Contents (Affiliates listed alphabetically) A J S B K T C L U D M V E N W F O Y G P Z H Q National Affiliates I R Page 2 of 42 APC I051 | July 2021 South Australia We would like to acknowledge the generous support of the following venues and events that have agreed to accept the Companion Card. A A Day on the Green (National) ABC Collinswood Centre, Adelaide Aberfoyle Community Centre Adelaide 4WD and Adventure Show Adelaide Antique Fair Adelaide Aquatic Centre Adelaide Arena Adelaide Auto Expo and Hot Rod Show Adelaide Beer and Barbecue Festival Adelaide Boat Show Adelaide Chamber Singers Adelaide City Council (ACC) • Adelaide City Council (ACC) Adelaide Aquatic Centre • Adelaide City Council (ACC) Adelaide Golf Links • Adelaide City Council (ACC) Adelaide Town Hall Page 3 of 42 APC I051 | July 2021 South Australia Adelaide Convention Centre Adelaide Craft and Quilt Fair Adelaide Entertainment Centre Adelaide Fashion Festival Adelaide Festival Adelaide Festival Centre • Adelaide Festival Centre Dunstan Playhouse • Adelaide Festival Centre Festival Theatre • Adelaide Festival Centre Her Majesty’s Theatre • Adelaide Festival Centre Space Theatre Adelaide Festival of Ideas Adelaide Film Festival Adelaide Football Club Adelaide Fringe Inc. Adelaide Gaol Adelaide Gardening and Outdoor Living Show Adelaide Guitar Festival Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary Adelaide International Raceway Page 4 of 42 -

Pipe Organs and Organ Building in the Northern Territory of Australia

Pipe organs and organ building in the Northern Territory of Australia by D.B. Duncan Councillor, Organ Historical Trust of Australia June 2008 NT Organs St. Mary Star of the Sea Roman Catholic Cathedral, Smith Street, Darwin Residence of Michael Pfitzner Darwin Symphony Orchestra Introduction Organ building in the Northern Territory has been hampered by three major factors: the remoteness of the region, the smallness of its population; and the tropical climate that creates difficulties for the organ builder. Creating a pipe organ for climatic conditions has always taxed the skill of the organ builder and is often beyond the ability of builders more accustomed to milder climates. Quite apart from the extreme and prolonged heat and humidity of the tropics, there is also the devastating effect of cyclonic activity. This factor has been an important consideration in the supply of instruments to the northern regions of Australia. Nonetheless over a sixty year period from 1938 there have been three pipe organs in Darwin, two of which were in service and one installed but removed before it became playable. At the time of writing, there remains only one pipe organ in the Territory; the other two were removed in 1974. All of the central churches in Darwin city are serviced by electronic instruments, at least two of which are sophisticated modern organs of high calibre and quality. Only one of these churches has ever had a pipe organ. St. Mary Star of the Sea Roman Catholic Cathedral, Smith Street, Darwin 1938 E. F. Walcker & Cie, Ludwigsburg, Germany The organ and aboriginal choir c1960's The first St Mary’s Star of the Sea church was built by the Jesuits in the 1880s, and was destroyed within a few years by a cyclone. -

E-Tibia Jan-Feb 2020

PATRONS : Dr Robert Boughen OBE and David Gray Jan-Feb 2020 TOSAQ DIRECTORY COMING UP: President: Lance Hutchinson (07) 3355 0979 a/h DDaavviidd BBaaiilleeyy CCoonncceerrtt [email protected] Sunday 23 February at 2 pm Vice-President: Kelvin Grove State College Theatre Kevin Collins 3351 2322 [email protected] Treasurer: Kevin Purchase 3359 6016 [email protected] Executive Secretary: Brett Kavanagh 0412-879 678 [email protected] Tibia Editor: Mike Gillies (07) 3279 3930 [email protected] Committee Members: Come along to our first major concert event for David Bailey 2020. And who better to start off the new year Debbie Fitzsummons Robert Weismantel than our very own David Bailey! David will be John Rattray pulling out all stops (very apt on this occasion!) Murray Ries to present a full concert program of music on the Tim Larritt Christie cinema pipe organ plus two Laurel & Christie Maintenance: Hardy silent films we have not seen before. All Rick Whatson 0451-409 343 in air-conditioned comfort and it includes [email protected] afternoon tea. Bring your family and friends! Postal Address (all correspondence): See inside for more details. 51 Princess St, Mitchelton QLD 4053 TOSA QUEENSLAND was established on Club Day with Organ Access 26 Feb 1964 Sunday 1 March 2020 Bookings are essential for extended practice Unless otherwise noted, our daytime sessions from c. 10 am to 3 pm. Sessions meetings are held from 2 pm at Kelvin generally last an hour, but depending on Grove State College Theatre, corner of numbers, can be longer. Contact the Secretary Tank Street & Victoria Park Road, Kelvin Brett Kavanagh to nominate a time. -

Adelaide Fringe 15 February – 17 March 2019

1 AdelaIdE FringE 15 FebruArY – 17 March 2019 GUIDE FOR ARTISTS AND VENUES Presenting Partner Artwork based on poster design by Matthew Clarke 2 Adelaide. Designed for Life. cityofadelaide.com.au/explore 3 CONTENTS FringeWORKS: Your Home Away From Home 4 Fringe Awards 6 Fringe Club: By Night 7 Ticketing 10 Fringe In Rundle Mall 2019 12 Honey Pot: Adelaide's International Arts Marketplace 13 – Honey Pot Events 14 Getting Down To Business 17 Discovery Sessions 18 Connect 22 Hello Fringe artists and venues! I would like to extend a warm welcome to all the FringeWORKS Daytime Program 23 artists and venues of the 2019 Adelaide Fringe! It is hard to believe that our favourite time of year has come Beyond Fringe 27 around again! Thank you so much for all you do. You create Workshops 28 the magic and wonder that is Adelaide Fringe. Here’s to another unforgettable month of adventures. Fringe Fun! 30 This guide is full of incredibly useful information for Fringe Wellbeing 32 artists. This year the daytime program of events is bigger than ever! We have so many opportunities for you to make Flyering & Postering 33 the most of your Adelaide Fringe days – ranging from discovery Busking / Reviews / panels, workshops, info sessions and networking opportunities Accommodation 34 in the Fringe Club – you’re bound to discover something new, exciting and enlightening. There’s also wellbeing sessions and Getting Around 35 fun social events too. Cheap Eats 36 Check out the whole range of discounts around town that will help stretch your dollar further. Be sure you take advantage Beaches & Nature 39 of FringeWORKS in the Fringe Club; it’s open every day of the Artist Pass Discounts 40 festival! FringeWORKS is where you can get advice and support from the entire Artists & Venues team. -

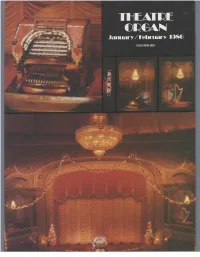

Theatre Organ Nevvs from Australia

are just off the Galeria. The Galeria is one of the most beautiful areas in the Biltmore with a coffered ceiling and three-dimensional sculptures as well as large surfaces covered with oil paintings set in a wheel mosaic and in terspersed with bronze filigrees. The Crystal Ballroom, which will be the scene of our banquet, has the most elaborate ceiling in the Biltmore. Mounted in its con cave, domed surface is a single canvas of great proportion decorated with goddesses, cupids, satyrs and other mythical figures. Two mam moth crystal lighting fixtures, imported from Europe, are suspended from the ceiling to add a truly glittering effect. Although these public spaces are designed after the palaces and cathedrals of Europe, the more than 700 guest rooms are newly dec orated in bright colors with plants and hang ing artwork (many by Jim Dine who is famous for his stylized depictions of hearts). Yes, "LA's the Place," and the Biltmore is the perfect setting for the headquarters of our 1987 Convention. D Sussex, U.K., and migrated to Australia in the 1970s. The acquisition follows the death Theatre Organ Nevvs of the former owner who was a TOSA mem ber. Organist Tony Fenelon travelled from his From Australia home in Melbourne to Adelaide recently to give two theatre organ concerts in two days to by appreciative audiences. The first took place on the 2/12 Wurlitzer (ex-Plaza Melbourne) Bruce installed in Wyatt Hall, Adelaide. The organ Ardley was in top condition, and it gave many of the audience great pleasure to hear it again. -

February 2014

The Friends Of Urrbrae House - Page 1 - Newsletter February 2014 The Friends of Urrbrae House Urrbrae House, University of Adelaide, Waite Campus, PMB#1 GLEN OSMOND, SA 5064. Tel 8313 7497 Editor Vicki Cheshire An exciting year ahead at Urrbrae House Whilst Urrbrae House is closed for repairs at the moment work is still going on in the background. University Staff are hard at work in their offices and The Friends of Urrbrae House Committee is actively planning the year’s events and fundraising programs. We are liaising with the management at Urrbrae House, other Friends groups and Vivente Music to present you with a full and varied year ahead. Please keep an eye out for some interesting opportunities to support Urrbrae House and have some fun and entertainment with us this year. 2014 Membership forms are included with this newsletter, we hope you will continue as Friends of Urrbrae House and make your contribution promptly. We endeavour to keep the costs of functions as low as possible but expenses increasingly eat into our profits. Should you have friends or family who would like to also become members please ask for a form at the next event or they can be found online at: https://waite.adelaide.edu.au/urrbraehouse/friends/FOUH_Membership_Application_Form.pdf Apart from fulfilling our obligations to members and the interests of Urrbrae House, the FOUH committee is always looking to expand its membership. More members mean more people with an interest and love for this magnificent mansion that was built in 1891, the Waite Family’s legacy to the university of Adelaide and Dates for your diary Agricultural Science in Australia. -

Maree Ackehurst

Rosanne Hosking Actor, Musical Theatre, Singer – E3 to E6, Dancer E: [email protected] M: 0417 873 713 W: www.aaa-talent.com.au Height: Hair colour: Eye colour: Dress/suit size: Age Range Ethnicity 177cm Brown Brown 32 - 42 Australian Education/Training 1991-94 BMus (Perf) Elder Conservatorium, Adelaide SA Vocal Training 2014-15 Naomi Eyers Adelaide SA 2011-12 Helen Tiller Adelaide SA 2001-02 Jennifer Caron United Kingdom 1999-2000 Amanda Colliver Sydney, NSW 1998-97 Kate Sadler Melbourne, VIC 1996 Valerie Collins-Varga Sydney, NSW 1995-96 Christa Leahmann Sydney, NSW 1998 Louise Malloy Auckland, NZ 1991-94 Rae Cocking Adelaide, SA Acting Tuition 1994-96 Drop in Classes The Actors Centre, Sydney Dance Tuition 1994-98 Casual Ballet Classes with Pauline Allison 1994 Private Ballet Tuition with Sheree da Costa Educational Experience 2013-Present Music/Singing Lecturer at Adelaide College of the Arts 2012-Present Singing Teacher at Concordia College 2012-Present Singing Teacher/Lecturer at Tabor College 2006-Present Private Voice Teacher/Coach 2006-Present Vocal Tutor Music Theatre Camp SA, Presented by Pelican Productions 2012 Vocal/Choir Director for the Sing!OZ Community Choir project 2012 Presented “Stage Presence and Song Interpretation” workshop to SA Primary Schools Festival Choir 2011-12 Presented “Vocal Technique” workshop to Pelican Production’s Winter Camp 2009-11 Presented workshops to SA Primary Schools Music Festival soloists “Stage Presence and Song Interpretation” 2009 Presented “Teaching Vocal Technique” workshop to -

Download Adelaide Festival Guide

03 Contents Welcomes (pg 04) Late Night in the Cathedral: The Lola’s Pergola (pg 08) Complete Motets of JS Bach (pg 54) Sound Introversion Radio (pg 55) Theatre WOMADelaide (pg 70) Roman Tragedies (pg 10) Dance Green Porno (pg 20) Needles and Opium (pg 22) Sadeh21 (pg 18) AM I (pg 38) An Iliad (pg 24) Blackout (pg 40) The Shadow King (pg 26) The Curious Scrapbook Adelaide Writers' Week of Josephine Bean (pg 28) Adelaide Writers’ Week (pg 56) Windmill Theatre Trilogy (pg 29) Kids’ Days (pg 60) Girl Asleep, Fugitive, School Dance Comics Can Do Anything (pg 61) Fight Night (pg 32) Visual Arts Kiss of the Chicken King (pg 34) BigMouth (pg 35) Adelaide International: This Filthy World Vol. 2 (pg 36) Worlds in Collision (pg 62) The Seagull (pg 37) Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Dark Heart (pg 64) Music Four Rooms (pg 66) Free Opening Night Party (pg 06) Artists’ Week (pg 68) Zorn in Oz (pg 12) Film Masada Marathon, Triple Bill (Zorn & Laswell Duo, Essential Cinema, Cobra), River of Fundament (pg 16) Classical Marathon, Zorn@60 DocWeek (pg 71) Tectonics Adelaide (pg 41) More Unsound Adelaide (pg 44) Snowtown: Live, Stars of the Lid, Dig It @ The Museum (pg 72) Morton Subotnick, Bookings (pg 73) Nurse With Wound, The Haxan Cloak, Access (pg 74) Moritz von Oswald Trio, Emptyset, Gardland Map (pg 75) Rime of the Ancient Mariner (pg 48) Staff and supporters (pg 76) dirtsong (pg 50) Join us online (pg 77) Continuum (pg 52) Kelemen Quartet (pg 53) Adelaide Festival 2014 Welcome 05 Jay Weatherill David Sefton Premier of South Australia Artistic Director Welcome to the 2014 Adelaide Festival.