Song of the Exile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DP Une Vie Simple

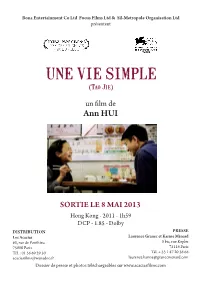

Bona Entertainment Co Ltd Focus Films Ltd & Sil-Metropole Organisation Ltd présentent UNE VIE SIMPLE (Tao Jie) un film de Ann HUI SORTIE LE 8 MAI 2013 Hong Kong - 2011 - 1h59 DCP - 1.85 - Dolby DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Les Acacias Laurence Granec et Karine Ménard 63, rue de Ponthieu 5 bis, rue Kepler 75008 Paris 75116 Paris Tél. : 01 56 69 29 30 Tél. + 33 1 47 20 36 66 [email protected] [email protected] Dossier de presse et photos téléchargeables sur www.acaciasfilms.com SYNOPSIS Au service d’une famille bourgeoise depuis quatre générations, la domestique Ah Tao vit seule avec Roger, le dernier héritier. Producteur de cinéma, il dispose de peu de temps pour elle, qui, toujours aux petits soins, continue de le materner... Le jour où elle tombe malade, les rôles s’inversent... ENTRETIEN AVEC ANN HUI Votre film s'inspire de la vie de Roger Lee, un célèbre producteur de cinéma à Hong Kong. Comment avez-vous eu l’idée de faire un film sur lui ? Roger Lee est le producteur du film. On s'est rencontré et il m'a raconté son histoire qui m'a beaucoup plu, et à partir de là, nous avons commencé à rechercher des finan - cements. Je voulais faire un film autour d'une histoire simple concernant les relations de travail entre une domestique et son patron dans le Hong Kong des années 60-70. À quelle occasion avez-vous rencontré Roger Lee pour la première fois ? Roger était co-producteur sur Neige d'été , un film que j'ai réalisé et qui est sorti en 1995. -

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(S): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol

The New Hong Kong Cinema and the "Déjà Disparu" Author(s): Ackbar Abbas Source: Discourse, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring 1994), pp. 65-77 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41389334 Accessed: 22-12-2015 11:50 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Discourse. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 142.157.160.248 on Tue, 22 Dec 2015 11:50:37 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The New Hong Kong Cinema and the Déjà Disparu Ackbar Abbas I For about a decade now, it has become increasinglyapparent that a new Hong Kong cinema has been emerging.It is both a popular cinema and a cinema of auteurs,with directors like Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Allen Fong, John Woo, Stanley Kwan, and Wong Rar-wei gaining not only local acclaim but a certain measure of interna- tional recognitionas well in the formof awards at international filmfestivals. The emergence of this new cinema can be roughly dated; twodates are significant,though in verydifferent ways. -

Narrative Space in the Cinema of King Hu 127

interstate laws directed against the telegraph, the telephone, and the railway, see Questions of Chinese Aesthetics: Film Form and Ferguson and McHenry, American Federal Government, 364, and Harrison, "'Weak- ened Spring,'" 70. Narrative Space in the Cinema of King Hu 127. Mosse, Nationalism and Sexuality. by Hector Rodnguez 128. Goldberg, Racist Culture. Much of the concern over the Johnson fight films was directed at the effects they would have on race relations (e.g., the possibility of black people becoming filled with "race pride" at the sight ofjohnson's victories). This imperialistic notion of reform effectively positioned black audiences as need- In memory of King Hu (1931-1997) ing moral direction. 129. Orrin Cocks, "Motion Pictures," Studies in Social Christianity (March 1916): 34. The concept of Chinese aesthetics, when carefully defined and circumscribed, illu- minates the relationship between narrative space and cultural tradition in the films of King Hu. Chinese aesthetics is largely based on three ethical concerns that muy be termed nonattachment, antirationalism, and perspectivism. This essay addresses the representation of "Chineseness" in the films of King Hu, a director based in Hong Kong and Taiwan whose cinema draws on themes and norms derived from Chinese painting, theater, and literature. Critical discussions of his work have often addressed the question of the ability of the cinema, a for- eign medium rooted in a mechanical age, to express the salient traits of Chinas longstanding artistic traditions. At stake is the relationship between film form and the national culture, embodied in the concept of a Chinese aesthetic. Film scholars tend to define the main features of Chinese aesthetics selec- lively, emphasizing a few stylistic norms out of a broad repertoire of available his- tones and traditions, and the main criterion for this selection is the sharp difference between those norms and the presumed realism of European art before modern- ism. -

Zz027 Bd 45 Stanley Kwan 001-124 AK2.Indd

Statt eines Vorworts – eine Einordnung. Stanley Kwan und das Hongkong-Kino Wenn wir vom Hongkong-Kino sprechen, dann haben wir bestimmte Bilder im Kopf: auf der einen Seite Jacky Chan, Bruce Lee und John Woo, einsame Detektive im Kampf gegen das Böse, viel Filmblut und die Skyline der rasantesten Stadt des Universums im Hintergrund. Dem ge- genüber stehen die ruhigen Zeitlupenfahrten eines Wong Kar-wai, der, um es mit Gilles Deleuze zu sagen, seine Filme nicht mehr als Bewe- gungs-Bild, sondern als Zeit-Bild inszeniert: Ebenso träge wie präzise erfährt und erschwenkt und ertastet die Kamera Hotelzimmer, Leucht- reklamen, Jukeboxen und Kioske. Er dehnt Raum und Zeit, Aktion in- teressiert ihn nicht sonderlich, eher das Atmosphärische. Wong Kar-wai gehört zu einer Gruppe von Regisseuren, die zur New Wave oder auch Second Wave des Hongkong-Kinos zu zählen sind. Ihr gehören auch Stanley Kwan, Fruit Chan, Ann Hui, Patrick Tam und Tsui Hark an, deren Filme auf internationalen Festivals laufen und liefen. Im Westen sind ihre Filme in der Literatur kaum rezipiert worden – und das will der vorliegende Band ändern. Neben Wong Kar-wai ist Stanley Kwan einer der wichtigsten Vertreter der New Wave, jener Nouvelle Vague des Hongkong-Kinos, die ihren künstlerischen und politischen Anspruch aus den Wirren der 1980er und 1990er Jahre zieht, als klar wurde, dass die Kronkolonie im Jahr 1997 von Großbritannien an die Volksrepublik China zurückgehen würde. Beschäftigen wir uns deshalb kurz mit der historischen Dimension. China hatte den Status der Kolonie nie akzeptiert, sprach von Hong- kong immer als unter »britischer Verwaltung« stehend. -

Entire Dissertation Noviachen Aug2021.Pages

Documentary as Alternative Practice: Situating Contemporary Female Filmmakers in Sinophone Cinemas by Novia Shih-Shan Chen M.F.A., Ohio University, 2008 B.F.A., National Taiwan University, 2003 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Novia Shih-Shan Chen 2021 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY SUMMER 2021 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Declaration of Committee Name: Novia Shih-Shan Chen Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Thesis title: Documentary as Alternative Practice: Situating Contemporary Female Filmmakers in Sinophone Cinemas Committee: Chair: Jen Marchbank Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Helen Hok-Sze Leung Supervisor Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Zoë Druick Committee Member Professor, School of Communication Lara Campbell Committee Member Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Christine Kim Examiner Associate Professor, Department of English The University of British Columbia Gina Marchetti External Examiner Professor, Department of Comparative Literature The University of Hong Kong ii Abstract Women’s documentary filmmaking in Sinophone cinemas has been marginalized in the film industry and understudied in film studies scholarship. The convergence of neoliberalism, institutionalization of pan-Chinese documentary films and the historical marginalization of women’s filmmaking in Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the People’s Republic of China (PRC), respectively, have further perpetuated the marginalization of documentary films by local female filmmakers. -

Sesiones ESPECIALES 8 1/2 WOMAN

SEsIONES ESPECIALES 8 1/2 WOMAN 8 1/2 WOMAN Producción: Kees Kasander, para Delux Productions, Continent Films, Movie Master, Woodline Productions. Nacionalidad: Netherlands/United Kingdom/ Luxembourg/Germany 1999. Directed: Peter Greenaway. Guión: Peter Greenaway. Fotografía. Sacha Vierny. Color. Vestuario: Emi Wada. Montaje: Elmer Leupen. Intérpretes: John Standing, Matthew Delamere, Vivian Wo, Annie Shizuka Inoh, Barbara Sarafian, Kirina Mano, Toni Collette, Amanda Plummer, Natacha Amal, Manna Fujiwara, Polly Walker, Elizabeth Berrington , Myriam Muller, Don Warrington, Claire Johnston. Duración: 120 min. V.O.S.E. 8 1/2 Woman es un penetrante e innovador estudio sobre el sexo, el poder, las clases sociales, las culturas, la mujer... Peter Greenaway explora las relaciones entre hombres y mujeres y el sexo en uno de sus films más logrados de los últimos años, en el que retoma su obsesión por las simetrías, los números y las estructuras artificiales, aunque en favor de una trama más accesible y hasta divertida. Un adinerado hombre de unos 55 años pierde a su esposa de toda la vida. Queda desolado por la tristeza. Su hijo intenta consolarlo, le propone reunir a un grupo de mujeres en un castillo y descubrir una sexualidad aún latente. Mujeres con las que ambos experimentarán libremente. 8 y 1/2 mujeres, de distintas procedencias culturales y sociales, son llamadas a integrar el harén. Todas lo hacen a cambio de algo. Con el tiempo, no mucho, padre e hijo se darán cuenta que las mujeres empiezan a desafiar su poder y que son criaturas más complejas que simples pedazos de carne. Una a una se alejan casi hastiadas de la presencia masculina. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

1 “Ann Hui's Allegorical Cinema” Jessica Siu-Yin Yeung to Cite This

This is the version of the chapter accepted for publication in Cultural Conflict in Hong Kong: Angles on a Coherent Imaginary published by Palgrave Macmillan https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-7766-1_6 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/34754 “Ann Hui’s Allegorical Cinema” Jessica Siu-yin Yeung To cite this article: By Jessica Siu-yin Yeung (2018) “Ann Hui’s Allegorical Cinema”, Cultural Conflict in Hong Kong: Angles on a Coherent Imaginary, ed. Jason S. Polley, Vinton Poon, and Lian-Hee Wee, 87-104, Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018. Allegorical cinema as a rhetorical approach in Hong Kong new cinema studies1 becomes more urgent and apt when, in 2004, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) begins financing mainland Chinese-Hong Kong co-produced films.2 Ackbar Abbas’s discussion on “allegories of 1997” (1997, 24 and 16–62) stimulates studies on Happy Together (1997) (Tambling 2003), the Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002–2003) (Marchetti 2007), Fu Bo (2003), and Isabella (2006) (Lee 2009). While the “allegories of 1997” are well- discussed, post-handover allegories remain underexamined. In this essay, I focus on allegorical strategies in Ann Hui’s post-CEPA oeuvre and interpret them as an auteurish shift from examinations of local Hong Kong issues (2008–2011) to a more allegorical mode of narration. This, however, does not mean Hui’s pre-CEPA films are not allegorical or that Hui is the only Hong Kong filmmaker making allegorical films after CEPA. Critics have interpreted Hui’s films as allegorical critiques of local geopolitics since the beginning of her career, around the time of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984 (Stokes and Hoover 1999, 181 and 347 note 25), when 1997 came and went (Yau 2007, 133), and when the Umbrella Movement took place in 2014 (Ho 2017). -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

A Man of Many Parts Musician, Actor, Director, Producer — Teddy Robin Remembers the Milestones of His Illustrious Showbiz Career Spanning More Than 50 Years

CHINA DAILY | HONG KONG EDITION Friday, July 5, 2019 | 9 Culture profi le A man of many parts Musician, actor, director, producer — Teddy Robin remembers the milestones of his illustrious showbiz career spanning more than 50 years. Mathew Scott listened in. eddy Robin carries with him an it,” says Robin. “I think it was because of want to see them. Some directors make air of enthusiasm that can lift Beatle-mania. I don’t think I handled the fi lms that are too arty. If people don’t see Teddy Robin earned fame as a rock your mood. fame very well. I was shocked.” your fi lms, what’s the use of them?” star but always knew his path would It has you smiling, before you lead him to films. ROY LIU / CHINA DAILY knowT it, almost as broadly as Robin him- A life in the movies Seeking out the best self does when asked fi rst-up if he’s ever Much of the attention, as always in the It’s a point that leads us directly to why thought about the reason behind his run music world, was focused on the lead sing- Robin has come to HKAC. He had a hand of success in the world of Asian entertain- er with the light, bright voice and the fi lm in around 50 fi lms across his career, from ment for more than 50 years. industry in Hong Kong was quick to notice early box-o ce hits such as his debut in “Fate!” is the initial, rapid-fi re response, how the fans fl ocked to Robin. -

An Interview with Ann Hui Visible Secrets: Hong Kong's Women

An Interview with Ann Hui Visible Secrets: Hong Kong’s Women Filmmakers Your 21st century films are quite eclectic. What has driven your choice of projects in recent times? I shot Visible Secrets after two years' teaching and I thought, first, I'd better do a film that was marketable. My first film is also a thriller and I thought it was fun to revisit old grounds. Then followed a film which I was really interested in making (July Rhapsody ), I thought I would never be able to raise funds for it but surprisingly it was accepted by the investor, so I made it. And so forth and so on... alternately, making films I really want to make and some I could just make so as to survive in the industry. Could you talk a little about The Way We Are and Night and Fog? These films seem quite different stylistically; one very much informed by social realism and the other more melodramatic, yet each seems perfect for its subject matter. What made you select these different approaches to the setting of Tin Shui Wai? The Way We Are was initially planned as a D.V. affair since I couldn’t find the money for Night and Fog . It's also initially not about Tin Shui Wai but I decided to transport the whole setting to Tin Shui Wai. The script was already written 7 or 8 years ago about another housing estate but since I knew Tin Shui Wai well, and the lifestyle of all these housing areas are about the same, I thought it would be okay to transpose the whole story to the newest housing estate. -

Speaking in Tongues by Stephanie Han English Standards Are Falling! If You Concur and Believe That the City Is Facing a Linguistic Crisis, You Are in the Majority

Speaking in Tongues by Stephanie Han English standards are falling! If you concur and believe that the city is facing a linguistic crisis, you are in the majority. What you might be surprised to hear is that in 2001, 40% of the population identified themselves as bilingual. Language skills all around have improved. If you’re a typical Hong Konger there’s a good chance your grandmother, like 78% of the women in 1931, couldn’t read or write in any language. Perhaps the illusion of halcyon days of Hong Kong when everyone was speaking “good English” offer sanctuary in difficult times. Prof. Kingsley Bolton of the University of Hong Kong’s Department of English, editor of Hong Kong English: Autonomy and Creativity says, “People need to take a broad view. They have this idea of a mythical golden age they thought existed, when everyone spoke perfect English, maybe in the 1960s when Anson Chan and Martin Lee were at the University of Hong Kong. But I highly suspect that the English they used wasn’t different than the English that Hong Kong students speak today.” Part of the problem is Hong Kong’s increased expectations is that its base has switched from manufacturing to technology and financial services; more people are speaking multiple languages than ever before, but there’s also a demand for a high level of fluency. Fulfilling the government mandate of a trilingual (English, Cantonese and Mandarin) bi-literate (Chinese and English) society in order to keep step with the changing times is impossible without fully examining questions of nationalism and facing the reality of globalized business.