Architecture and Phenomenology Brendan O’Byrne, Patrick Healy, Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aesthetica Issue 100 Celebrations

Aesthetica Magazine commemorates 100 issues, launching the milestone edition at the Future Now Symposium, with a dedicated day of innovative masterclasses. Aesthetica Magazine reaches a significant milestone in 2021, publishing the 100th issue of the magazine, and marking 18 years of independent publishing. This special edition will be launched with a full day of virtual talks at the Future Now Symposium (28 April), celebrating one of the UK’s leading art and culture publications, founded in York, UK. Kicking the day off, between 09.30 and 10.30, audiences can hear from both of Aesthetica’s founders, Cherie Federico and Dale Donley, to learn more about the journey of starting Aesthetica Magazine as a project and developing the publication into one of the world’s leading voices for art and design, with a reach of 500,000, as well as a platform for creativity across the Art Prize, Creative Writing Award and Film Festival. A series of talks bring the 100th issue of Aesthetica to life, including an examination of international lighting design with Sarah Schleuning, Dallas Museum of Art; and Cindi Strauss, Museum of Fine Arts Houston. From the invention of the first electric light by Humphry Davy in 1808 to Phillips’ development of the “ultraefficient” lightbulb in 2011, lighting technology has fascinated engineers, scientists and designers worldwide. This session brings the last century of into focus. Hear from some of our favourite photographers over the years, including Ellie Davies, Kevin Cooley, Ryan Schude, Yannis Davy Guibinga and Brooke DiDonato. In this creative panel discussion, we ask: how do you take a photograph in a new way? How far can you push the ideas in order to create something that is captivating and also contributes to wider discourse on image-making? Closing the first day of the festival, at 18.30-19.30, 100th issue cover photographer Kriss Munsya considers the power of images to reclaim identities and tackle internalised structures. -

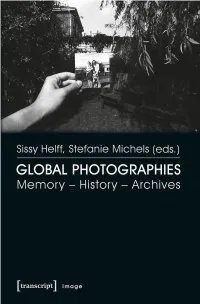

Global Photographies

Sissy Helff, Stefanie Michels (eds.) Global Photographies Image | Volume 76 Sissy Helff, Stefanie Michels (eds.) Global Photographies Memory – History – Archives An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3006-4. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non- commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contac- ting [email protected] © 2018 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Cover concept: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Cover illustration: Sally Waterman, PastPresent No. 6, 2005, courtesy of the artist Proofread and typeset by Yagmur Karakis Printed by docupoint GmbH, Magdeburg Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-3006-0 PDF-ISBN -

One Month to Go Until the Aesthetica

One Month to Go until BAFTA Qualifying Aesthetica Short Film Festival 2016 In one month’s time, the BAFTA Qualifying Aesthetica Short Film Festival (ASFF) 2016 will open its doors to filmmakers, audiences, and industry professionals, brought together in celebration of independent film, and in championing and supporting emerging and established practitioners. Screenings The sixth edition of the festival presents the largest programme to date with 400 films, offering festival-goers an unprecedented opportunity to explore the diversity of short film in genres such as drama, animation, documentary, fashion, experimental, comedy, thriller and music video. The Official Selection unites artists from across the world, showcasing filmmaking talent from a total of 40 countries worldwide. Audiences can shape their festival experience according to their own preferences, choosing from Single Screening Tickets to catch a short snippet of what’s on offer to a full Four Day Unlimited Pass – permitting access to all screenings including Special Showcases from the UK’s leading cultural institutions including Creative England, London College of Fashion, Plymouth College of Art, Northern Ireland Screen, University of York and more. Committed to bringing unique and timely films to audiences, ASFF 2016 also presents a special screening of Battle of the Somme to mark the film’s Centenary, in partnership with The Imperial War Museum, London. The film presented a pivotal moment in World War One history to audiences across Britain in 1916, and will be shown at York Army Museum every day of the festival. Venues ASFF is a festival of discovery, not only inviting its attendees to experience something new in short film from its innovative Official Selection filmmakers, but also encouraging them to explore the city of York. -

Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020

Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 phaidon.com Phaidon New Titles Winter/Spring 2020 Art Fashion Art = Discovering Infinite Connections in Art History 6 The Fashion Book, revised & updated edition 74 Yoshitomo Nara 10 Peter Saul: Crime and Punishment 12 Video/Art: The First Fifty Years 14 General interest Korean Art from 1953: Collision, Innovation, Interaction 16 Adrián Villar Rojas, Contemporary Artists Series 18 Map: Exploring the World, midi format 76 Bernar Venet, Contemporary Artists Series 20 Grow Fruit & Vegetables in Pots: Planting Advice Phaidon Colour Library: Dalí, Klimt, Monet, Picasso, & Recipes from Great Dixter 78 and Van Gogh 22 The Gardener’s Garden, 2020 edition, midi format 80 Photography Travel Robert Mapplethorpe 24 Wallpaper* City Guides 82 Stephen Shore: American Surfaces, revised & expanded edition 26 Steve McCurry: India 28 Children’s Books Our World: A First Book of Geography 88 Food & Cooking My Art Book of Happiness 90 Yayoi Kusama Covered Everything in Dots Around the World with Phaidon’s Bestselling and Wasn’t Sorry. 92 Global Culinary Bibles 30 Animals in the Sky 94 The Irish Cookbook 32 First Concepts with Fine Artists: Cooking in Marfa: Welcome, We’ve Been A Collection of Five Books 96 Expecting You 34 Ages & Stages 98 Ana Roš: Sun and Rain 36 The Vegetarian Silver Spoon 38 The Silver Spoon: Recipes for Babies 40 Phaidon Collections What is Cooking 42 Phaidon Collections 104 Architecture Recently Published Where Architects Sleep: The Most Stylish Hotels in the World -

As the Former In-House Art Director for Photographer Annie Leibovitz, Tim Helped Ms

TIM HOSSLER The University of Kansas, School of Architecture, Design & Planning, Department of Design 1465 Jayhawk Blvd., Marvin Studios, Room 136, Lawrence, KS 66045 305.205.3097, [email protected], timhosslerdesign.tumblr.com BIO As the former in-house art director for photographer Annie Leibovitz, Tim helped Ms. Leibovitz create her most memorable images, books and exhibitions of the late 90’s through the early 2000’s. Tim holds a degree in Architecture from Kansas State University, 1993, and a MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art, 2005. He has held the positions of Director of Design at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MoCA) and Art Director of The Wolfsonian-Florida International University in Miami Beach. He currently teaches design history, photo culture and visual communications at the University of Kansas. His academic research focuses on working with photographers, artists and cultural institutions to produce experimental forms of visual narratives. He is currently focused on the research and development of Looking for Havana, the first book in an ongoing series which will serve as a time capsule to a changing city. These guides will explore how visual culture defines our ideas of place. 1/37 CV TIM HOSSLER The University of Kansas, School of Architecture, Design & Planning, Department of Design 1465 Jayhawk Blvd., Marvin Studios, Room 136, Lawrence, KS 66045 305.205.3097, [email protected], timhosslerdesign.tumblr.com EDUCATION 2005 Master of Fine Arts (MFA), 2D Design Cranbrook Academy of Art, Bloomfield Hills, Michigan -

Future Now 2021

The Future Now Symposium finds a new home in an online space for 2021, bringing together 100 speakers, 30 events and 4 days of live events. The Future Now Symposium returns for its sixth edition, doubling its length as a four-day arts festival exploring the mechanisms of art and culture with a significantly expanded programme of panel discussions, expert masterclasses, portfolio reviews and advice sessions, running live 28 April – 1 May, and is then available On Demand 2-31 May. This momentous four-day event brings together global institutions, galleries, publications and artists for discussion on the most pressing issues in today’s creative industries, from inclusivity and diverse programming to understanding the art market in a rapidly changing industry. This year, the sessions are available to stream from the comfort of your home. We’re also presenting an expansive programme of 100 ground-breaking films across the genres of Dance, Experimental, Documentary and Artists’ Film. The Future Now platform can be accessed on computers, smart TVs, smart phones and all tablet devices, with tickets starting from £20. Key topics for 2021 include Environmental Photography: How Can Images Save Us?; Curating During a Time of Change; Documentary & Ethics: When is it Your Story to Tell?; Digital Ecologies: Three-Dimensional Storytelling; The Business of Art: The Future of Collecting; Women Street Photographers: Reshaping the Canon; Arts Opportunities: What’s Available Post-Pandemic; Fine Art, Hip Hop, Pop Culture; and Deep Fakes: Control and Subversion in Art. Speakers include representatives from MoMA, New York; High Museum, Atlanta, Fondazione Prada, Milan; Tate, London; Gagosian, New York; International Center of Photography, New York; Leica Galleries; ICA Boston; MASS MoCA, Massachusetts; and British Council, as well as individual artists such as Fahamu Pecou, George Byrne, Athi- Patra Ruga, Bieke Depoorter, Shirin Neshat, Jane & Louise Wilson, and more. -

ALEC SOTH Bibliography Selected Publications

ALEC SOTH Bibliography Selected Publications 2019 Soth, Alec. I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating. London: MACK, 2019. 2018 Soth, Alec. Alec Soth: Niagara. London: MACK, 2018. 2015 Penhall, Michele M. Stories from the Camera: Reflections on the Photograph. Albuquerque: University of Mexico, 2015. Schuman, Aaron and Kate Bush. Gathered Leaves, London: MACK, 2015. 2014 Fraenkel, Jeffrey ed. The Plot Thickens. San Francisco: Fraenkel Gallery, 2014. Knight, Robert. In Context: The Portrait in Contemporary Photographic Practice. Clinton, New York: Ruth and Elmer Wellin Museum of Art, 2014. Soth, Alec. Songbook. Minnesota: Little Brown Mushroom, 2014. “The Secret Lives of Museum Guards,” The New Yorker, September 26, 2015. “Voyages: Visual Journeys by six photographers,” The New York Times Magazine, September 26, 2015. 2013 Dyer, Geoff and Pico Iyer. Ping Pong. St. Paul, Minnesota: Little Brown Mushroom, September 2013. Soth, Alec and Brad Zellar. Three Valleys. St. Paul, Minnesota: Little Brown Mushroom, March 2013. 2012 Soth, Alec. Looking for Love 1996. Berlin: Kominek Books, 2012. Soth, Alec and Brad Zellar. Ohio. St. Paul, Minnesota: Little Brown Mushroom, May 2012. Soth, Alec and Brad Zellar. Upstate. St. Paul, Minnesota: Little Brown Mushroom, August 2012. Soth, Alec and Brad Zellar. Michigan. St. Paul, Minnesota: Little Brown Mushroom, November 2012. 2011 Alec Soth: Mostly Women. Portland, Oregon: Nazraeli Press, 2011. Soth, Alec. Alec Soth: La Belle Dame Sans Merci. 2011. Soth, Alec. Lonley Boy Mag (No. A-1: Alec Soth’s Midwestern Exotica). St. Paul, Minnesota: Little Brown Mushroom Books, March 2011. 2010 Rodarte, Catherine Opie, Alec Soth. Zurich: JRP Ringier, 2010. Soth, Alec. -

Art & Architecture Source

Art & Architecture Source Database Coverage List "Core" coverage refers to sources which are indexed and abstracted in their entirety (i.e. cover to cover), while "Priority" coverage refers to sources which include only those articles which are relevant to the field. This title list does not represent the Selective content found in this database. The Selective content is chosen from thousands of titles containing articles that are relevant to this subject. *Titles with 'Coming Soon' in the Availability column indicate that this publication was recently added to the database and therefore few or no articles are currently available. If the ‡ symbol is present, it indicates that 10% or more of the articles from this publication may not contain full text because the publisher is not the rights holder. Please Note: Publications included on this database are subject to change without notice due to contractual agreements with publishers. Coverage dates shown are the intended dates only and may not yet match those on the product. All coverage is cumulative. Due to third party ownership of full text, EBSCO Information Services is dependent on publisher publication schedules (and in some cases embargo periods) in order to produce full text on its products. Coverage Policy Source Type ISSN Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Full Text Start Full Text Stop Full Text Peer- PDF Image Abstracting Start Abstracting Stop Delay Review Images QuickVie (Months) ed (full w page) Core Magazine #3 Collection Journal 3 02/01/2013 02/01/2013 Core Book / Monograph 97807136 300 Years of Industrial Design A&C Black Publishers Ltd. -

7.10 Nov 2019 Grand Palais

PRESS KIT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST, YANCEY RICHARDSON, NEW YORK, AND STEVENSON CAPE TOWN/JOHANNESBURG CAPE AND STEVENSON NEW YORK, RICHARDSON, YANCEY OF THE ARTIST, COURTESY © ZANELE MUHOLI. © ZANELE 7.10 NOV 2019 GRAND PALAIS Official Partners With the patronage of the Ministry of Culture Under the High Patronage of Mr Emmanuel MACRON President of the French Republic [email protected] - London: Katie Campbell +44 (0) 7392 871272 - Paris: Pierre-Édouard MOUTIN +33 (0)6 26 25 51 57 Marina DAVID +33 (0)6 86 72 24 21 Andréa AZÉMA +33 (0)7 76 80 75 03 Reed Expositions France 52-54 quai de Dion-Bouton 92806 Puteaux cedex [email protected] / www.parisphoto.com - Tel. +33 (0)1 47 56 64 69 www.parisphoto.com Press information of images available to the press are regularly updated at press.parisphoto.com Press kit – Paris Photo 2019 – 31.10.2019 INTRODUCTION - FAIR DIRECTORS FLORENCE BOURGEOIS, DIRECTOR CHRISTOPH WIESNER, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR - OFFICIAL FAIR IMAGE EXHIBITORS - GALERIES (SECTORS PRINCIPAL/PRISMES/CURIOSA/FILM) - PUBLISHERS/ART BOOK DEALERS (BOOK SECTOR) - KEY FIGURES EXHIBITOR PROJECTS - PRINCIPAL SECTOR - SOLO & DUO SHOWS - GROUP SHOWS - PRISMES SECTOR - CURIOSA SECTOR - FILM SECTEUR - BOOK SECTOR : BOOK SIGNING PROGRAM PUBLIC PROGRAMMING – EXHIBITIONS / AWARDS FONDATION A STICHTING – BRUSSELS – PRIVATE COLLECTION EXHIBITION PARIS PHOTO – APERTURE FOUNDATION PHOTOBOOKS AWARDS CARTE BLANCHE STUDENTS 2019 – A PLATFORM FOR EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHY IN EUROPE ROBERT FRANK TRIBUTE JPMORGAN CHASE ART COLLECTION - COLLECTIVE IDENTITY -

Review of Pop Art Design at Barbican Centre, London

8/9/2018 Aesthetica Magazine - Review of Pop Art Design at Barbican Centre, London Magazine Shop Awards Directory Advertise Review of Pop Art Design at Barbican Centre, London Aesthetic Intelligent, be informative, A of the leading art, design an Sign up to the newsletter: Your email S With the Barbican hosting its finale, this comprehensive review of the relationship between Pop Art and design from Vitra Design Museum has just gone up a notch: its European tour finishing on a high with the addition of works from leading British institutions such as the V&A, Tate and many private collectors. These 200 works are housed within a curvaceous set designed by AOC Architecture and Village Green Studio, immediately transporting visitors into the bold and mischievous world of Pop Art. Pop Art may often be disregarded as gaudy, garish and indulgent, however this exhibition reveals its deeply historical nature: a post-war phenomenon, reacting to the effects of mass-production, mass-media and mass-culture, with a focus on the American Dream, celebrity and the seductive femme fatale. Although the exhibition is vast, it is divided thematically – Barbican’s Lower Level a playful combination of art and design pieces, which miraculously manage to portray around 30 years of art history in one fell swoop; and the Upper Level a sleek selection of design pieces, acting as a break-out space after the near- information-overload of the floor below. The fine art dimension of the exhibition is not just a collection of Warhols, Hamiltons and Lichtensteins (although the key names are well represented), but also ventures into Pop Art film – William Klein’s dark take on the psychedelic city spectacle particularly memorable. -

Concept 2017-06

June 2017 conceptabstraction image conceptualisation notion thought impression theory view conception idea hypothesis e-newsletter Hi folks, I am very pleased to be presenting my first edition of Concept and it is particularly good to be working with our former editor, Christine, who In this Issue will continue to manage the layout of the newsletter. I am a very keen amateur photographer and a member of the RPS North East Contemporary North-east Contemporary Group, the Travel Group, and the North-east Group Meeting March 2017 Documentary Group. As you can see, my interests are wide ranging and I love a challenge, which is probably as well given the new role I Magnum SWAPS have taken on! South West Contemporary I am still working my way into the role and I look forward in the next Group Meeting June 2017 few months to getting to know people within the larger group. The East Anglia Group one thing I believe passionately is that our e newsletter is a brilliant Update vehicle for keeping all the Contemporary Group members in touch wherever we come from. Contemporary Group Questionnaire Results The newsletter can only ever be as good as the content we receive from you, the members, so please do send me any news, future events, Neil Wittman at the reports, exhibitions in your area, images, or interesting projects you are Kunsthuis working on. I am planning to produce Concept every two months and in our next edition I am introducing a Gallery Page which I do hope North East Contemporary Group Meeting May 2017 everybody will feel able to contribute to. -

Remnants of Existence: Discovering Value in Loss Andrea Hardin Garland Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2019 Remnants of Existence: Discovering Value in Loss Andrea Hardin Garland Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Garland, Andrea Hardin, "Remnants of Existence: Discovering Value in Loss" (2019). All Theses. 3068. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3068 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMNANTS OF EXISTENCE: DISCOVERING VALUE IN LOSS A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Fine Arts Visual Art by Andrea Hardin Garland May 2019 Accepted by: Professor Kathleen Thum, Committee Chair Professor David Detrich Dr. Beth Lauritis ABSTRACT Those who precede us in the continuum of humanity may affect our lives even if we are unaware of their influence. To illustrate the residue of previous generations, I emboss textiles inherited from my Southern American family. Formerly useful and distinctly decorative, these embroidered handkerchiefs, crocheted doilies, lace nightgowns and dress gloves are now antiquated curiosities. Using the force of a printing press, I form shadowy impressions of the articles on paper to communicate presence in absence, then manipulate the images with various media. I literally rinse, wring and dry many of these works in an effort to elevate the accepted understanding of domestic labor usually undertaken by women. Subverting the act of washing, I then apply smudges, streaks and line drawings to deepen the surface texture.