Theatre Fires and Disaster Sociology by Daniel F. Devlin Submitted to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supreme Court of the United States

1 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Monday, October 13, 1902. The court met pursuant to law. Present : The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice Brown, Mr. Justice Shiras, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham and Mr. Justice McKenna. Warren K. Snyder of Oklahoma City, Okla., Joseph A. Burkart of Washington, D. C, Robert H. Terrell of Washington, D. C, Robert Catherwood of Chicago, 111., Sardis Summerfield of Reno, Nev., J. Doug- las Wetmore of Jacksonville, Fla., George D. Leslie of San Francisco, Cal., William R. Striugfellow of New Orleans, La., P. P. Carroll of Seattle, Wash., P. H. Coney of Topeka, Kans., H. M. Rulison of Cin- cinnati, Ohio, W^illiam Velpeau Rooker of Indianapolis, Ind., Isaac N. Huntsberger of Toledo, Ohio, and Charles W. Mullan of Waterloo, Iowa, were admitted to practice. The Chief Justice announced that all motions noticed for to-day would be heard to-morrow, and that the court would commence the call of the docket to-morrow pursuant to the twenty-sixth rule. Adjourned until to-morrow at 12 o'clock. The day call for Tuesday, October 14, will be as follows: Nos. 306, 303, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 and 12. O 8753—02 1 2 SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. Tuesday, October 14, 1902. Present: The Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Harlan, Mr. Justice Brewer, Mr. Justice Brown, Mr. Justice Shiras, Mr. Justice White, Mr. Justice Peckham and Mr. Justice McKenna. E. Howard McCaleb, jr., of New Orleans, La., Judson S. Hall of New York City, Elbert Campbell Ferguson of Chicago, 111., John Leland Manning of Chicago, 111., Alden B. -

The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology's Symposium: Cybercrime February 1, 2013 10:30 A.M

The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology's Symposium: Cybercrime February 1, 2013 10:30 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. Free and open to the public Northwestern University School of Law 375 E. Chicago Ave. Chicago, IL 60611 Lincoln Hall, Levy Mayer 104 Technology is dramatically changing the landscape of the criminal law. In the hands of both criminals and law enforcement, computers challenge individuals’ privacy and security, create new obstacles in trial practice for prosecutors and defense attorneys, and test the limits of our Constitution. This Symposium explores how the criminal justice system is evolving in response to the increasing use of computers and other technology to both commit and fight crime. 10:30 AM: Opening Remarks 11:00 AM - 12:30 PM: A Balancing Act - Preventing Cybercrime While Protecting Individual Rights Moderator: Joshua Kleinfeld, Assistant Professor of Law, Northwestern University School of Law David Gray, Associate Professor of Law, University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law David Thaw, Visiting Assistant Professor of Law, University of Connecticut School of Law, Fellow of the Information Society Project, Yale Law School David Glockner, Managing Director, Stroz Friedberg LLC; Former Chief, Criminal Division, United State's Attorney's Office, Northern District of Illinois Kenneth Dort, Partner in Intellectual Property and Chair of Technology Committee, Drinker Biddle & Reath, LLP 12:30 PM - 1:00 PM: Lunch 1:00 PM - 2:30 PM: Cybercrime in the Courtroom - Investigation and Trial Practice in a Networked World -

Fire Escapes in Urban America: History and Preservation

FIRE ESCAPES IN URBAN AMERICA: HISTORY AND PRESERVATION A Thesis Presented by Elizabeth Mary André to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Specializing in Historic Preservation February, 2006 Abstract For roughly seventy years, iron balcony fire escapes played a major role in shaping urban areas in the United States. However, we continually take these features for granted. In their presence, we fail to care for them, they deteriorate, and become unsafe. When they disappear, we hardly miss them. Too often, building owners, developers, architects, and historic preservationists consider the fire escape a rusty iron eyesore obstructing beautiful building façades. Although the number is growing, not enough people have interest in saving these white elephants of urban America. Back in 1860, however, when the Department of Buildings first ordered the erection of fire escapes on tenement houses in New York City, these now-forgotten contrivances captivated public attention and fueled a debate that would rage well into the twentieth century. By the end of their seventy-year heyday, rarely a building in New York City, and many other major American cities, could be found that did not have at least one small fire escape. Arguably, no other form of emergency egress has impacted the architectural, social, and political context in metropolitan America more than the balcony fire escape. Lining building façades in urban streetscapes, the fire escape is still a predominant feature in major American cities, and one has difficulty strolling through historic city streets without spotting an entire neighborhood hidden behind these iron contraptions. -

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems

Fire Service Features of Buildings and Fire Protection Systems OSHA 3256-09R 2015 Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 “To assure safe and healthful working conditions for working men and women; by authorizing enforcement of the standards developed under the Act; by assisting and encouraging the States in their efforts to assure safe and healthful working conditions; by providing for research, information, education, and training in the field of occupational safety and health.” This publication provides a general overview of a particular standards- related topic. This publication does not alter or determine compliance responsibilities which are set forth in OSHA standards and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Moreover, because interpretations and enforcement policy may change over time, for additional guidance on OSHA compliance requirements the reader should consult current administrative interpretations and decisions by the Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission and the courts. Material contained in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced, fully or partially, without permission. Source credit is requested but not required. This information will be made available to sensory-impaired individuals upon request. Voice phone: (202) 693-1999; teletypewriter (TTY) number: 1-877-889-5627. This guidance document is not a standard or regulation, and it creates no new legal obligations. It contains recommendations as well as descriptions of mandatory safety and health standards. The recommendations are advisory in nature, informational in content, and are intended to assist employers in providing a safe and healthful workplace. The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to comply with safety and health standards and regulations promulgated by OSHA or by a state with an OSHA-approved state plan. -

My Wonderful World of Slapstick

THE THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF Georgia State Bo»r* of Education AN. PR,CLAun\;v eSupt of School* 150576 DECATUR -DeKALB LIBRARY REGIONAI SERVICE ROCKDALE COUNTY NEWTON COUNTY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from Media History Digital Library http://archive.org/details/mywonderfulworldOObust MY WONDERFUL WORLD OF SLAPSTICK MY WO/VDERFUL WORLD OF SLAPSTICK BUSTER KEATON WITH CHARLES SAMUELS 150576 DOVBLEW& COMPANY, lNC.,<k*D£H C(TYt HlW Yo*K DECATUR - DeKALB LIBRARY REGiOMA! $&KZ ROCKDALE COUNTY NEWTON COUNTY Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 60-5934 Copyright © i960 by Buster Keaton and Charles Samuels All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America First Edition J 6>o For Eleanor 1. THE THREE KEATONS 9 2. I BECOME A SOCIAL ISSUE 29 3. THE KEATONS INVADE ENGLAND 49 4. BACK HOME AGAIN IN GOD'S COUNTRY 65 5. ONE WAY TO GET INTO THE MOVIES 85 6. WHEN THE WORLD WAS OURS 107 7. BOFFOS BY MAN AND BEAST 123 8. THE DAY THE LAUGHTER STOPPED 145 9. MARRIAGE AND PROSPERITY SNEAK UP ON ME 163 10. MY $300,000 HOME AND SOME OTHER SEMI-TRIUMPHS 179 11. THE WORST MISTAKE OF MY LIFE 199 12. THE TALKIE REVOLUTION 217 13. THE CHAPTER I HATE TO WRITE 233 14. A PRATFALL CAN BE A BEAUTIFUL THING 249 15. ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL 267 THE THREE KeAtOnS Down through the years my face has been called a sour puss, a dead pan, a frozen face, The Great Stone Face, and, believe it or not, "a tragic mask." On the other hand that kindly critic, the late James Agee, described my face as ranking "almost with Lin- coln's as an early American archetype, it was haunting, handsome, almost beautiful." I cant imagine what the great rail splitter's reaction would have been to this, though I sure was pleased. -

Board Meeting Packet

Board of Directors Board Meeting Packet December 5, 2017 Clerk of the Board YOLANDE BARIAL KNIGHT (510) 544-2020 PH MEMO to the BOARD OF DIRECTORS (510) 569-1417 FAX EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT East Bay Regional Park District Board of Directors BEVERLY LANE The Regular Session of the December 5, 2017 President - Ward 6 Board Meeting is scheduled to commence at 1:00 p.m. at the EBRPD Administration Building, DENNIS WAESPI 2950 Peralta Oaks Court, Oakland Vice President - Ward 3 AYN WIESKAMP Treasurer - Ward 5 ELLEN CORBETT Secretary - Ward 4 Respectfully submitted, WHITNEY DOTSON Ward 1 DEE ROSARIO Ward 2 COLIN COFFEY ROBERT E. DOYLE Ward 7 General Manager ROBERT E. DOYLE General Manager P.O. Box 5381 2950 Peralta Oaks Court Oakland, CA 94605-0381 (888) 327-2757 MAIN (510) 633-0460 TDD (510) 635-5502 FAX www.ebparks.org AGENDA REGULAR MEETING OF DECEMBER 5, 2017 BOARD OF DIRECTORS EAST BAY REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT The Board of Directors of 11:30 a.m. ROLL CALL (Board Conference Room) the East Bay Regional Park District will hold a regular meeting at District’s PUBLIC COMMENTS Administration Building, 2950 Peralta Oaks Court, Oakland, CLOSED SESSION CA, commencing at 11:30 a.m. for Closed Session and 1:00 p.m. A. Conference with Labor Negotiator: Government Code Section 54957.6 for Open Session on Tuesday, December 5, 2017. 1. Agency Negotiator: Robert E. Doyle, Ana M. Alvarez Agenda for the meeting is Employee Organizations: AFSCME Local 2428, listed adjacent. Times for agenda Police Association items are approximate only and Unrepresented Employees: Managers and Confidentials are subject to change during the meeting. -

On and Off the Cliff

The Newsletter of The Cliff Dwellers ON AND OFF THE CLIFF Volume 39, Number 2 March-April 2017 International Women’s Day-2017: Be Confident in Your Power! By Mike Deines CD’03 International Women’s Day had its roots in the labor movements at the turn of the Twentieth Century in North America and across Europe. The United Nations began celebrating IWD on March 8 during International Women’s Year in 1975, and two years later the U.N. General Assembly proclaimed a United Nations Day for Women’s Rights and International Peace to be observed by Member States in accordance with their historical and national traditions. In essence, IWD is a time to reflect on progress made, to call for social change, and to celebrate acts of courage and determination by ordinary women who have played an extraordinary role in the history of their countries and communities. The Cliff Dwellers at the urging of then President Leslie Eve Moran introduced Recht CD’03 became part of IWD celebrations in 2011. The Club IWD keynote speaker Andrea Kramer. has focused on bringing together a host of interesting women to inspire and guide the next generation of young women in Chicago. To that end, again this year a group of 30 scholars from nearby high schools (Chicago Tech Academy, Jones High School, and Muchin High School) shared lunch and inspiring stories with nearly 70 women and Club members. Eve Moran CD’10 once again organized and hosted the March 8 program. The keynote address was given by Andrea Kramer, a partner in an international law firm where she was a founding member of the firm’s Diversity Committee. -

AMERICAN MANHOOD in the CIVIL WAR ERA a Dissertation Submitted

UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael E. DeGruccio _________________________________ Gail Bederman, Director Graduate Program in History Notre Dame, Indiana July 2007 UNMADE: AMERICAN MANHOOD IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA Abstract by Michael E. DeGruccio This dissertation is ultimately a story about men trying to tell stories about themselves. The central character driving the narrative is a relatively obscure officer, George W. Cole, who gained modest fame in central New York for leading a regiment of black soldiers under the controversial General Benjamin Butler, and, later, for killing his attorney after returning home from the war. By weaving Cole into overlapping micro-narratives about violence between white officers and black troops, hidden war injuries, the personal struggles of fellow officers, the unbounded ambition of his highest commander, Benjamin Butler, and the melancholy life of his wife Mary Barto Cole, this dissertation fleshes out the essence of the emergent myth of self-made manhood and its relationship to the war era. It also provides connective tissue between the top-down war histories of generals and epic battles and the many social histories about the “common soldier” that have been written consciously to push the historiography away from military brass and Lincoln’s administration. Throughout this dissertation, mediating figures like Cole and those who surrounded him—all of lesser ranks like major, colonel, sergeant, or captain—hem together what has previously seemed like the disconnected experiences of the Union military leaders, and lowly privates in the field, especially African American troops. -

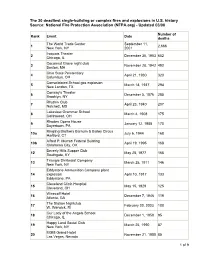

National Fire Protection Association (NFPA.Org) - Updated 03/08

The 20 deadliest single-building or complex fires and explosions in U.S. history Source: National Fire Protection Association (NFPA.org) - Updated 03/08 Number of Rank Event Date deaths The World Trade Center September 11, 1 2,666 New York, NY 2001 Iroquois Theater 2 December 30, 1903 602 Chicago, IL Cocoanut Grove night club 3 November 28, 1942 492 Boston, MA Ohio State Penitentiary 4 April 21, 1930 320 Columbus, OH Consolidated School gas explosion 5 March 18, 1937 294 New London, TX Conway's Theater 6 December 5, 1876 285 Brooklyn, NY Rhythm Club 7 April 23, 1940 207 Natchez, MS Lakeview Grammar School 8 March 4, 1908 175 Collinwood, OH Rhodes Opera House 9 January 12, 1908 170 Boyertown, PA Ringling Brothers Barnum & Bailey Circus 10a July 6, 1944 168 Hartford, CT Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building 10b April 19, 1995 168 Oklahoma City, OK Beverly Hills Supper Club 12 May 28, 1977 165 Southgate, KY Triangle Shirtwaist Company 13 March 25, 1911 146 New York, NY Eddystone Ammunition Company plant 14 explosion April 10, 1917 133 Eddystone, PA Cleveland Clinic Hospital 15 May 15, 1929 125 Cleveland, OH Winecoff Hotel 16 December 7, 1946 119 Atlanta, GA The Station Nightclub 17 February 20, 2003 100 W. Warwick, RI Our Lady of the Angels School 18 December 1, 1958 95 Chicago, IL Happy Land Social Club 19 March 25, 1990 87 New York, NY MGM Grand Hotel 20 November 21, 1980 85 Las Vegas, Nevada 1 of 9 Major Building Fires Source: Report on Large Building Fires and Subsequent Code Changes Jim Arnold, Assoc. -

Annual Report 2017 - 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 2018 Details Make a Difference www.historicrichmond.com 1 FROM OUR LEADERSHIP Details Make A Difference In our Spring Newsletter, we discussed stepping back to look at “The Big Picture” and how our Vision came into Focus with a shared set of Preservation Values. With that Big Picture now in focus, it is also clear that the Details Make All the Difference. The details are what connect us across generations to those that walked these streets before us. It is the details that connect us to the lives and struggles – both large and small – of those people in these places. For two centuries, an upturned torch at Monumental Church has reflected the lives extinguished too soon by the Richmond Theatre Fire. For more than a century, an eagle on the General Assembly Building’s 1912 façade stood sentinel watching over our Capitol. Several blocks away, another eagle, radiator grill in its grasp (and tongue in cheek), signaled the advent of the automobile. Exceptional craftsmanship has stood the test of time in Virginia Union University’s “nine noble” buildings of Virginia granite. This attention to detail said “We are strong. We are solid. And we will strive and succeed for centuries to come.” It is seemingly insignificant details such as these that help us to understand that our lives are significant – that our actions can - and do - make an impact on the world around us. We are excited to have rolled up our sleeves to focus on those details. In this report, we share with you an update on our work in 2017-2018, including: Preservation • Monumental Church • Masons’ Hall Revitalization • Neighborhood Revitalization Projects Rehabilitation • Westhampton School • Downtown Revitalization/ Blues Armory Advocacy & Education • Master Planning • Rehab Expo • Lecture Programs • Golden Hammer Awards Cover Photo: Painting the east stairwell of Monumental Church thanks to the Elmon B. -

1907 Journal of General Convention

Journal of the General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America 1907 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL OF THE GENERAL CONVENTION OF THE -roe~tant epizopal eburib IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Held in the City of Richmond From October Second to October Nineteenth, inclusive In the Year of Our Lord 1907 WITH APPENDIcES PRINTED FOR THE CONVENTION 1907 SECRETABY OF THE HOUSE OF DEPUTIES. THE REV. HENRY ANSTICE, D.D. Office, 281 FOURTH AVE., NEW YORK. aTo whom, as Secretary of the Convention, all communications relating to the general work of the Convention should be addressed; and to whom should be forwarded copies of the Journals of Diocesan Conventions or Convocations, together with Episcopal Charges, State- ments, Pastoral Letters, and other papers which may throw light upon the state of the Church in the Diocese or Missionary District, as re- quired by Canon 47, Section II. -

Read This Issue

Look to the rock from which you were hewn Vol. 28, No. 1, Winter 2004 chicago jewish historical society chicago jewish history IN THIS ISSUE Martin D. Kamen— Science & Politics in the Nuclear Age From the Archives: Synagogue Project Dr. Louis D. Boshes —Memorial Essay & Oral History Excerpts “The Man with the Golden Fingers” Report: Speaker Ruth M. Rothstein at CJHS Meeting Harold Fox measures Rabbi Morris Gutstein of Congregation Shaare Tikvah for a kosher suit. Courtesy of Harold Fox. African-American (Nate Duncan), and one Save the Date—Sunday, March 21 Mexican (Hilda Portillo)—who reminisce Author Carolyn Eastwood to Present about interactions in the old neighborhood and tell of their struggles to save it and the “Maxwell Street Kaleidoscope” Maxwell Street Market that was at its core. at Society Open Meeting Near West Side Stories is the winner of a Book Achievement Award from the Midwest Dr. Carolyn Eastwood will present “Maxwell Street Independent Publishers’ Association. Kaleidoscope,” at the Society’s next open meeting, Sunday, There will be a book-signing at the March 21 in the ninth floor classroom of Spertus Institute, 618 conclusion of the program. South Michigan Avenue. A social with refreshments will begin at Carolyn Eastwood is an adjunct professor 1:00 p.m. The program will begin at 2:00 p.m. Invite your of Anthropology at the College of DuPage friends—admission is free and open to the public. and at Roosevelt University. She is a member The slide lecture is based on Dr. Eastwood’s book, Near West of the CJHS Board of Directors and serves as Side Stories: Struggles for Community in Chicago’s Maxwell Street recording secretary.