Library Expansion Project Cambridge, Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citicorp Center + Citigroup Center + 601 Lexington (Current)

http://www.601lexington.com/gallery/?pp_fID_1156=504 Ana Larranaga | Allie McGehee | Lisa Valdivia | Madison Van Pelt | Yiwen Zhang Location: 601 Lexington Avenue + 54th Street, New York NY 10022 Other Names: CitiCorp Center + CitiGroup Center + 601 Lexington (Current) Architects: Hugh Stubbins, William LeMessurier Chief Structural Engineer: William LeMessurier Years Built: 1974 - 1977 Year Opened: 1977 Cost: $195,000,000 http://adamkanemacchia.com/gallery/home/_akm0205-edit/ - CitiCorp Center is the first skyscraper in the U.S to be built with a tuned mass damper - The tower is the 6th highest building in NYC - The building was built for commercial office - Design for the building was drawn by William LeMessurier on his restaurant napkin - The office lobby was renovated in 1997 and a new lobby was built in 2010 - The structure was being fixed secretly at night Born: January 11th, 1912 - July 5th 2006 Birthplace: Birmingham, Alabama Education: Georgia Institute of Technology(Undergrad) Harvard University (Masters) Firm: Hugh Stubbins and Associates (won one of the 1st AIA Firm Awards) Projects: CitiCorp Center, Boston’s Federal Reserve Bank, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, Landmark tower in Yokohama Awards: Gold Medal (Tau Sigma Delta), Honor Award AIA 1979 Born: June 1926 - June 2007 Birthplace: Pontiac, Michigan Education: Harvard University(BA Mathematics), Harvard Graduate School of Design, MIT (Masters in Engineering) Firm: LeMessurier Consultants Projects: Mah - LeMessurier System, Staggered Truss System, Tuned Mass Damper, -

A Week at the Fair; Exhibits and Wonders of the World's Columbian

; V "S. T 67>0 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ""'""'"^ T 500.A2R18" '""''''^ "^"fliiiiWi'lLi£S;;S,A,.week..at the fair 3 1924 021 896 307 'RAND, McNALLY & GO'S A WEEK AT THE FAIR ILLUSTRATING THE EXHIBITS AND WONDERS World's Columbian Exposition WITH SPECIAL DESCRIPTIVE ARTICLES Mrs. Potter Palmer, The C6untess of Aberdeen, Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer, Mr. D. H. Burnh^m (Director of Works), Hon. W. E. Curtis, Messrs. Adler & Sullivan, S. S. Beman, W. W. Boyington, Henry Ives Cobb, W, J. Edbrooke, Frank W. Grogan, Miss Sophia G. Havden, Jarvis Hunt, W. L. B. Jenney, Henry Van Brunt, Francis Whitehouse, and other Architects OF State and Foreign Buildings MAPS, PLANS, AND ILLUSTRATIONS CHICAGO Rand, McNally & Company, Publishers 1893 T . sod- EXPLANATION OF REFERENCE MARKS. In the following pages all the buildings and noticeable features of the grounds are indexed in the following manner: The letters and figures following the names of buildings in heavy black type (like this) are placed there to ascertain their exact location on the map which appears in this guide. Take for example Administration Building (N i8): 18 N- -N 18 On each side of the map are the letters of the alphabet reading downward; and along the margin, top and bottom, are figures reading and increasing from i, on the left, to 27, on the right; N 18, therefore, implies that the Administration Building will be found at that point on the map where lines, if drawn from N to N east and west and from 18 to 18 north and south, would cross each other at right angles. -

Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp

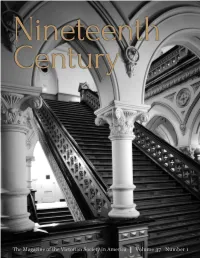

Nineteenth Ce ntury The Magazine of the Victorian Society in America Volume 37 Number 1 Nineteenth Century hhh THE MAGAZINE OF THE VICTORIAN SOCIETY IN AMERICA VOLuMe 37 • NuMBer 1 SPRING 2017 Editor Contents Warren Ashworth Consulting Editor Sara Chapman Bull’s Teakwood Rooms William Ayres A LOST LETTER REVEALS A CURIOUS COMMISSION Book Review Editor FOR LOCkwOOD DE FOREST 2 Karen Zukowski Roberta A. Mayer and Susan Condrick Managing Editor / Graphic Designer Wendy Midgett Frank Furness Printed by Official Offset Corp. PERPETUAL MOTION AND “THE CAPTAIN’S TROUSERS” 10 Amityville, New York Michael J. Lewis Committee on Publications Chair Warren Ashworth Hart’s Parish Churches William Ayres NOTES ON AN OVERLOOkED AUTHOR & ARCHITECT Anne-Taylor Cahill OF THE GOTHIC REVIVAL ERA 16 Christopher Forbes Sally Buchanan Kinsey John H. Carnahan and James F. O’Gorman Michael J. Lewis Barbara J. Mitnick Jaclyn Spainhour William Noland Karen Zukowski THE MAkING OF A VIRGINIA ARCHITECT 24 Christopher V. Novelli For information on The Victorian Society in America, contact the national office: 1636 Sansom Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 (215) 636-9872 Fax (215) 636-9873 [email protected] Departments www.victoriansociety.org 38 Preservation Diary THE REGILDING OF SAINT-GAUDENS’ DIANA Cynthia Haveson Veloric 42 The Bibliophilist 46 Editorial 49 Contributors Jo Anne Warren Richard Guy Wilson 47 Milestones Karen Zukowski A PENNY FOR YOUR THOUGHTS Anne-Taylor Cahill Cover: Interior of richmond City Hall, richmond, Virginia. Library of Congress. Lockwood de Forest’s showroom at 9 East Seventeenth Street, New York, c. 1885. (Photo is reversed to show correct signature and date on painting seen in the overmantel). -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural.Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL.HISTORIANS OCTOBER 1969 VOL . XIII, NO.5 PUBLISHED SIX TIMES A YEAR BY THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS 1700 WALNUT STREET, PHILADELPHIA, PA. 19103 HENRY A. MILLON, PRESIDENT EDITOR: JAMES C. MASSEY, 614 S. LEE STREFT, ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22314. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: MARIAN CARD DONNELLY, 2175 OLIVE STREET, EUGENE, OREGON 97405 PRESIDENT'S MEMORANDUM 1970 Foreign Tour. Bavarian Baroque, August 18 - Sep tember 1, 1970. Jurgen Paul, Kunsthistorisches Institut, There are several matters passed by the Board of Directors that I would like to call to your attention: University of Tiibingen, will be tour Chairman. Although the main emphasis will be on Baroque, some mediaeval 1. The vote of the Board to create a new class of mem towns and churches and nineteenth-century architecture bership requires a change in our Bylaws that will have to will be included. Announcement of the tour will be sent be ratified by the membership at the annual meeting. to the membership about November 1, 1969. Should you not plan to attend the meeting, please return the proxy that will accompany notice of the annual business Prize Contest. J . D. Forbes has generously offered $100 to any SAH member who can suggest a new and acceptable meeting. The new class of membership proposed is Joint stylistic term for United States domestic architecture of (husband-wife) with dues of $25.00 yearly. This class of membership will entitle the couple to full rights of member c . 1890 to c. 1910. Suggestions should be addressed to Executive Secretary, SAH, 1700 Walnut Street, Room 716, ship but only one copy of each issue of the Journal and Philadelphia, Pa. -

Hoch Cunningham Environmental Lectures Fall 2019

Hoch Cunningham Environmental Lectures Fall 2019 Fall 2019 - Hoch Cunningham Environmental Lectures INAUGURAL LECTURE – Coolidge Room, Ballou Hall Sep 5 Tamar Haspel The elephant in the room: Talking about Climate Change Sep 12 Eric Hines Offshore Wind and the Transition to Renewables Integrating Tropical Conservation and Civic Engagement to Create Sep 19 Jordan Karubian Change: a Case Study from Ecuador Can You Hear Me Here?: Sep 26 Leila Hatch Understanding and Protecting Underwater Soundscapes in US National Marine Sanctuaries Stephen Lester & Oct 3 Yankton Sioux Sacred Water Bundle Project * Kyle Monahan Oct 10 Jeff Dukes Ecosystem Responses to Climate Change Oct 17 Saya Ameli Habani Moral Disruption: Power of Youth to Make Lasting Change Oct 24 Nancy Selvage Sculpture Made in Response to Environmental Concerns Problems and Possibilities in Agroecology: Oct 31 Chris Conz an Historical Perspective from Lesotho, Southern Africa Nov 7 Anjuliee Mittelman Upstream Emissions from the Production and Transport of Fuels Nov 14 Keely Maxwell Disasters, Resilience, and the Environment Artist Talk: Nov 21 Georgie Friedman Metaphor, Meaning, Antarctica, and the Anthropocene (Oh my!) Dec 5 Kim Elena Ionescu Climate Change and Coffee: What Will We Be Drinking in Thirty Years? *This talk will be live-streamed but NOT recorded September 5, 2019 12:00-1:00pm | Coolidge Room, Ballou Hall INAUGURAL HOCH CUNNINGHAM ENVIRONMENTAL LECTURE Coolidge Room, Ballou Hall The Elephant in the Room: Talking about Climate Change Tamar Haspel, science journalist How did climate change become such a charged issue? It's gone from being an obscure field of study to a badge of identity, all in the last decade or so. -

The Urban and Architectural History of Denver, Colorado by Caitlin Anne Milligan

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Design Theses Fall 12-2015 Gold, Iron, and Stone: The rbU an and Architectural History of Denver, Colorado Caitlin A. Milligan Samfox School of Design and Visual Arts Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/samfox_arch_etds Part of the Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Milligan, Caitlin A., "Gold, Iron, and Stone: The rU ban and Architectural History of Denver, Colorado" (2015). Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design Theses. 2. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/samfox_arch_etds/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Design at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design Theses by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Architecture and Architectural History Thesis Examination Committee: Dr. Eric Mumford, Chair Dr. Robert Moore Gold, Iron, and Stone The Urban and Architectural History of Denver, Colorado by Caitlin Anne Milligan A thesis presented to the Graduate School of Design & Visual Arts of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architectural Studies (Concentration: the History -

Improving the Energy Efficiency and Environmental Impact of Historic Building

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation January 2008 Shades of Green: Improving the Energy Efficiency and Environmental Impact of Historic Building Anita M. Franchetti University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Franchetti, Anita M., "Shades of Green: Improving the Energy Efficiency and Environmental Impact of Historic Building" (2008). Theses (Historic Preservation). 105. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/105 A thesis in Historic Preservation Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Science in Historic Preservation 2008. Advisor: Michael C. Henry This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/105 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shades of Green: Improving the Energy Efficiency and Environmental Impact of Historic Building Abstract The recent dramatic increase in oil prices as well as a growing worldwide concern with climate change has brought renewed attention and interest in energy efficiency and consideration for the environment among all areas of industry, in particular the built environment. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, operational energy consumption in residential and commercial buildings accounted for 40% of total energy consumed in the United States in 2007, and produced nearly 48% of the country's greenhouse gas emissions. -

Annual Alumni Dinner: Reimagined

Northeastern University Civil Engineering Alumni Organization’s Annual Alumni Dinner: Reimagined Thursday, May 13, 2021 5:30 pm ET Online Content Page Content 2 Sponsors 3 Program 5 2020 Outstanding Alumna Award 8 2021 Outstanding Alumnus Award 11 Past Outstanding Alumnus/na Award Recipients 12 NUCEAO Communications 12 Office of Alumni Relations Communications Sponsors Thanks to all of our sponsors that help make the 2021 NUCEAO Annual Alumni Dinner: Reimagined possible. Platinum Gold Anonymous, in honor of retired Northeastern Vice President Jack Martin, DMSB’65, who developed the incredibly strong team culture of the Facilities department that led to so many successful projects even long after his retirement. Silver Special thank you to Short Path Distillery 2 Program Virtual Networking Reception Welcome Anna Dastgheib-Beheshti, E’15 President, NUCEAO Remarks from the Jerry Hajjar Department CDM Smith Professor and Chair, Civil and Environmental Engineering 2020 Outstanding Michael Tecci, E’03, MS’08 Alumna Award Recipient Maureen McDonough, E’82, Esq. 2021 Outstanding Michael Tecci, E’03, MS’08 Alumnus Award Recipient Peter Cheever, MS’80, PE NUCEAO Awards Michael Tecci, E’03, MS’08 Recipients Ryan Kloiber, E’21 Natasha Leipziger, E’21 Missy Muilenburg, E’21 Scholarship Introduction Anna Dastgheib-Beheshti, E’15 President, NUCEAO Leo F. Peters Scholarship Leo Peters, E’60, ME’66 in Civil Engineering Recipient Alice Ellis, E’21 3 Donald and Holly Pottle Donald Pottle, E’60, ME’66 Scholarship Recipients Peter Boticello, E’21 Regan Kelly, -

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947 Transcribed from the American Art Annual by Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director, Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Between 1897 and 1947 the American Art Annual and its successor volume Who's Who in American Art included brief obituaries of prominent American artists, sculptors, and architects. During this fifty-year period, the lives of more than twelve-hundred architects were summarized in anywhere from a few lines to several paragraphs. Recognizing the reference value of this information, I have carefully made verbatim transcriptions of these biographical notices, substituting full wording for abbreviations to provide for easier reading. After each entry, I have cited the volume in which the notice appeared and its date. The word "photo" after an architect's name indicates that a picture and copy negative of that individual is on file at the Maine Historic Preservation Commission. While the Art Annual and Who's Who contain few photographs of the architects, the Commission has gathered these from many sources and is pleased to make them available to researchers. The full text of these biographies are ordered alphabetically by surname: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z For further information, please contact: Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director Maine Historic Preservation Commission 55 Capitol Street, 65 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0065 Telephone: 207/287-2132 FAX: 207/287-2335 E-Mail: [email protected] AMERICAN ARCHITECTS' BIOGRAPHIES: ABELL, W. -

A Legacy of Leadership the Presidents of the American Institute of Architects 1857–2007

A Legacy of Leadership The Presidents of the American Institute of Architects 1857–2007 R. Randall Vosbeck, FAIA with Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA, and Andrew Brodie Smith THE AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS | WASHINGTON, D.C. The American Institute of Architects 1735 New York Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20006 www.aia.org ©2008 The American Institute of Architects All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-57165-021-4 Book Design: Zamore Design This book is printed on paper that contains recycled content to suppurt a sustainable world. Contents FOREWORD Marshall E. Purnell, FAIA . i 20. D. Everett Waid, FAIA . .58 21. Milton Bennett Medary Jr., FAIA . 60 PREFACE R. Randall Vosbeck, FAIA . .ii 22. Charles Herrick Hammond, FAIA . 63 INTRODUCTION Tony P. Wrenn, Hon. AIA . 1 23. Robert D. Kohn, FAIA . 65 1. Richard Upjohn, FAIA . .10 24. Ernest John Russell, FAIA . 67 2. Thomas U. Walter, FAIA . .13 25. Stephen Francis Voorhees, FAIA . 69 3. Richard Morris Hunt, FAIA . 16 26. Charles Donagh Maginnis, FAIA . 71 4. Edward H. Kendall, FAIA . 19 27. George Edwin Bergstrom, FAIA . .73 5. Daniel H. Burnham, FAIA . 20 28. Richmond H. Shreve, FAIA . 76 6. George Brown Post, FAIA . .24 29. Raymond J. Ashton, FAIA . .78 7. Henry Van Brunt, FAIA . 27 30. James R. Edmunds Jr., FAIA . 80 8. Robert S. Peabody, FAIA . 29 31. Douglas William Orr, FAIA . 82 9. Charles F. McKim, FAIA . .32 32. Ralph T. Walker, FAIA . .85 10. William S. Eames, FAIA . .35 33. A. Glenn Stanton, FAIA . 88 11. -

I. NAME of PROPERTY

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NTS Form l'~.<-9'~. USDI NTS KRHP Registration Foim illev. 8-861 UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD DEPOT Page 1 United States Department of the Interior. National Park Service______ National Register of Historic Places Resistration Form i. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Union Pacific Railroad Depot Other Name/Site Number: n/a 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 121 West 15rthm Street Not for publication: n/a City/Town: Cheyenne Vicinity: n/a State: Wyoming County: Laramie Code: 021 Zip Code: 82001 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: _ Building(s): _x Public-Local: _x_ District: Public-State: _ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 0 buildings 0 sites 0 structures 0 objects 0 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: J_ Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: n/a NTS Form lv-9"" USDI NTS XRHP Registration Foim illev. 8-861 UNION PACIFIC RAILROAD DEPOT Page 2 United States Department of (he Interior. National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. as amended. I hereby certify that this ___ nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ___ meets ___ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Amst 176 / Art 184: American Architecture 1860-Present

AmSt 176 / AH 191: American Architecture 1860-1940 Spring 2010 Professor Longstreth REFERENCE BIBLIOGRAPHY INDEX Surveys…………………………..................................................................................................................................3 Mid Nineteenth Century……………........................................................................................……………………….4 Late Nineteenth/Early Twentieth Centuries.......................................................................................…………………5 Interwar Decades.……...............................................................................................................……………………...7 Architects -- Nineteenth Century...................................................................................................……………………8 Architects -- Twentieth Century....................................................................................................…………………. 11 H. H. Richardson....................................................................................................................……………………….21 McKim, Mead & White............................................................................................................……………………...23 Louis Sullivan........................................................................................................................………………………..24 Frank Lloyd Wright…............................................................................................................…………………….…25 Local/Regional Studies….........................................................................................................……………………...30