Rap Gets Political Letters by K.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'expression Musicale De Musulmans Européens. Création De Sonorités Et

Revue européenne des migrations internationales vol. 25 - n°2 | 2009 Créations en migrations L’expression musicale de musulmans européens. Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse The Musical Expression of European Muslims. Creation of Tones in the Event of the Religious Norms La expresión musical de musulmanes europeos. Creación de sonoridades a la luz de las normas religiosas Farid El Asri Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/remi/4946 DOI : 10.4000/remi.4946 ISSN : 1777-5418 Éditeur Université de Poitiers Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 octobre 2009 Pagination : 35-50 ISBN : 978-2-911627-52-1 ISSN : 0765-0752 Référence électronique Farid El Asri, « L’expression musicale de musulmans européens. Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse », Revue européenne des migrations internationales [En ligne], vol. 25 - n°2 | 2009, mis en ligne le 01 octobre 2012, consulté le 17 mars 2021. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/remi/4946 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.4946 © Université de Poitiers Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales, 2009 (25) 2 pp. 35-50 35 L’expression musicale de musulmans européens Création de sonorités et normativité religieuse Farid EL ASRI* La présence musulmane en Europe est, pour une grande partie, originellement issue de l’immigration (Göle, 2005 ; Modood, Triandafyllidou, Zapata-Barrero, 2006 ; Nielsen, 1984 ; Nielsen, 1995 ; Parsons et Smeeding, 2006). Cette présence est également alimentée par des conversions à l’islam1 (Alliévi, 1998 ; Alliévi, 1999 ; Alliévi and Robert Schuman Centre, 2000 ; Minet, 2007 ; Rocher et Cherqaoui, 1986). Ses origines ne sont certainement pas monolithiques. Elle est originaire de nombreuses aires culturelles musul- manes. -

Blacko • 22H15 - 23H30 : Nemo

Dossier de presse Orléans, le mardi 16 juin 2015 Mairie d’Orléans - Festival Hip Hop Orléans 2015 Programme de la soirée du 27 juin Jardin de l’Evêché 18h-minuit Programme de la soirée du samedi 27 juin au Jardin de l'Evêché : • 18h30 - 19h : Black Jack • 19h15 - 19h45 : Nemo • 20h - 20h45 : Radikal MC • 21h - 22h : Blacko • 22h15 - 23h30 : Nemo 18h30 - 19h : Black Jack Artiste de rap orléanais, ancien membre du groupe Democrates D. 19h15 - 19h45 : Nemo (DJ orléanais) Le Captain Nemo a toujours été actif sur la scène rap d'Orléans. Animateur d'une émission spécialisée pendant 10 ans, il est aussi à l'origine du label Nautilus Recordz et membre du groupe Antipode. En produisant des disques et organisant de nombreux concerts et soirées, il a aidé à développer ce style musical dans la région orléanaise depuis la fin des années 90. Maintenant journaliste et DJ pour l’Abcdr du Son, le webzine rap de référence en France, Nemo continue de défricher la musique actuelle, toujours friand de nouveautés et d'innovations multimédia. Il proposera donc une sélection pointue mais dansante, un mix liant toutes ses influences, une recette pour tous les goûts." 20h - 20h45 : Radikal MC Radikal MC a tout juste dix ans quand il découvre le rap en 1997, à travers des artistes comme Kery James, IAM, Diam's ou encore le Saïan Supa Crew. L'évidence est flagrante, son amour pour le rap est né. Il crée alors son premier groupe avec deux amis d'enfance et écrit son premier texte. Entre 2001 et 2005, il enchaine ses premières séances d'enregistrement au sein du studio de la mythique association "Mouvement Authentique" (New Generation MC, Les Littles, EJM, Saliha...) et se succèdent les premiers concerts et premières parties d'artistes tels que Sinik ou encore le 113. -

Quarante Ans De Rap En France

Quarante ans de rap français : identités en crescendo Karim Hammou, Cresppa-CSU, 20201 « La pensée de Négritude, aux écrits d'Aimé Césaire / La langue de Kateb Yacine dépassant celle de Molière / Installant dans les chaumières des mots révolutionnaires / Enrichissant une langue chère à nombreux damnés d'la terre / L'avancée d'Olympe de Gouges, dans une lutte sans récompense / Tous ces êtres dont la réplique remplaça un long silence / Tous ces esprits dont la fronde a embelli l'existence / Leur renommée planétaire aura servi à la France2 » Le hip-hop, musique d’initiés tributaire des circulations culturelles de l’Atlantique noir Trois dates principales marquent l’ancrage du rap en France : 1979, 1982 et 1984. Distribué fin 1979 en France par la maison de disque Vogue, le 45 tours Rappers’ Delight du groupe Sugarhill Gang devient un tube de discothèque vendu à près de 600 000 exemplaires. Puis, dès 1982, une poignée de Français résidant à New York dont le journaliste et producteur de disques Bernard Zekri initie la première tournée hip hop en France, le New York City Rap Tour et invite le Rocksteady Crew, Grandmaster DST et Afrika Bambaataa pour une série de performances à Paris, Londres, mais aussi Lyon, Strasbourg et Mulhouse. Enfin, en 1984, le musicien, DJ et animateur radio Sidney lance l’émission hebdomadaire « H.I.P. H.O.P. » sur la première chaîne de télévision du pays. Pendant un an, il fait découvrir les danses hip hop et les musiques qui les accompagnent à un public plus large encore, et massivement composé d’enfants et d’adolescents. -

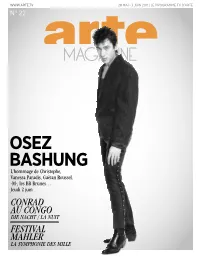

Osez Bashung

WWW.Arte.tv 28 MAI › 3 JUIN 2011 | LE PROGRAMME TV D’ARTE N° 22 OSEZ BASHUNG L’hommage de Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, Gaëtan Roussel, -M-, les BB Brunes… Jeudi 2 juin CONRAD AU CONGO DIE NacHT / LA NUIT FESTIVAL MAHLER LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE ARTE LIVE WEB ARTE LIVE WEB PARTENAIRE DU FESTIVAL DE FÈS MUSIQUES SaCRÉES DU MONDE DU 3 AU 12 JUIN 2011 Ben Harper, Youssou Ndour, Abd Al Malik, Maria Bethânia... Retrouvez les concerts sur arteliveweb.com LES GRANDS RENDEZ-VOUS SAMEDI 28 MAI › VENDREDI 3 JUIN 2011 “Ainsi pénétrions- nous plus avant chaque jour au cœur des ténèbres.” Joseph Conrad dans Die Nacht / La Nuit, mardi 31 mai à 0.50 Lire pages 6-7 et 19 SOULOY / GAMMA BASHUNG Une évocation inspirée du chanteur de “La nuit je mens”, à travers les voix de l’album hommage Tels - Alain Bashung : Christophe, Vanessa Paradis, -M-, Gaëtan Roussel, les BB Brunes... Jeudi 2 juin à 22.20 Lire pages 4-5 et 23 LA SYMPHONIE DES MILLE DIRIGÉE PAR RICCARDO CHAILLY Pour le concert de clôture du Festival Mahler de Leipzig, Riccardo Chailly ILS SE MARIÈRENT dirige la Symphonie n° 8 du composi- PATHÉ teur disparu il y a tout juste cent ans. ET EURENT BEAUCOUP Dimanche 29 mai à 18.15 Lire page 12 D’ENFANTS La crise de la quarantaine perturbe le quotidien de Vin- cent et Gabrielle, tout comme celui de leurs amis. Une comédie d’Yvan Attal drôle et touchante qui vous cueille sans prévenir. Avec Charlotte Gainsbourg, lumineuse. Jeudi 2 juin à 20.40 Lire page 22 N° 22 – Semaine du 28 mai au 3 juin 2011 – ARTE Magazine 3 EN COUVErtURE ARÈME C UDOVIC L BASHUNG PAR LES BB BRUNES C’est l’une des plus belles promesses de la scène rock française. -

Vol. 13.05 / June 2013

Vol. 13.05 News From France June 2013 A free monthly review of French news & trends France and Germany Co-Host EU Open House; Part of “Franco-German Year” © SDG/RP/ST © SDG/RP/ST © SDG/RP/ST © SDG © SDG/RP/ST © SDG/RP/ST © SDG/RP/ST The Embassy of France welcomed some 4,500 visitors to its grounds on May 11. As part of the EU Open House, nearly 30 embassies of member countries belong- ing to the European Union joined in sharing European culture and diplomacy in Washington. The French and German embassies co-hosted this year. Story, p. 2 From the Ambassador’s Desk: A Monthly Message From François Delattre The past month has showcased an exceptionally centered on this year’s “Euro-American Celebration,” diverse set of French-American partnerships. In fields as part of the European Month of Culture all through May. broad as medicine, culture, and manufacturing, we’ve In the security arena, Jean-Yves Le Drian, France’s inside been proud to work with our American friends. Minister of Defense, made a successful visit to Washing- Leading medical organizations in France and the ton on May 17 for meetings with, among many others, Current Events 2 U.S. joined together on May 7 to sign with me a Memo- U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel. The trip allowed May as European Month of Culture randum of Intent aimed at deepening for very close dialogue on global security Interview with the Expert 3 research on addiction. France’s National challenges, including Mali, Syria, Iran, and Amb. -

Hip Hop in Relation to Minority Youth Culture in France Amanda

Hip Hop in Relation to Minority Youth Culture in France Amanda Cottingham In 1991, the French Minister of Culture, Jack Lang, invited three rap groups to perform at the prime minister’s garden party at the Matignon palace for members of the National Assembly 1. French rappers today are not all on such amicable terms with politicians but are widely popular among the younger generations, a fact that was noted when riots broke out in 2005. Many of these rappers embrace immigrant communities, bringing their issues to the forefront because several are of foreign descent themselves, particularly Arabic North Africans. While the government might want to preserve a traditional view of French culture, modern musicians are celebrating the cultural diversity immigrants bring to the nation. The rap genre has grown in popularity in France to such an extent that despite degenerating relationships with the government, rappers are able to show support for minority groups while maintaining a broad base of popular support from the youths. Unlike other popular forms of music that act simply as a form of entertainment, developments of rap in France show that it is closely linked to social issues facing minority youths. Hip hop is not, however, native to France but rather an imported style which originated in the United States, the South Bronx of New York in particular. In the early 1970s, a former gang member, Afrika Bambaataa organized a group called The Zulu Nation to draw disaffected youths away from gang fighting and instead towards music, dance, and graffiti in order to introduce them to the various elements of hip hop culture. -

Perspectives from French West Indian Literature

ON BEING WEST INDIAN IN POST-WAR METROPOLITAN FRANCE: PERSPECTIVES FROM FRENCH WEST INDIAN LITERATURE by ROSALIE DEMPSY MARSHALL A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of French Studies University of Birmingham 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. In memory of Gloria, Luddy, Dorcas and Harry Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Professor Jennifer Birkett, for her patience, encouragement, and good advice when these were sorely needed; and also Dr Conrad James, who helped to ease me into French West Indian writing at the beginning of my studies, and who supervised my research in Jennifer’s absence. I am grateful to my dear parents, who kept faith with me over several years, and gave me the time and space to pursue this piece of scholarship. Abstract Most research into contemporary French West Indian literature focuses on writing that stresses the significance of the plantation and urban cultures of the islands in the early to mid-twentieth century or, more recently, on the desire of some writers to explore broader trans-national influences or environments. -

Hip Hop Symphonique #3 Avec Dosseh, Sniper, Sofiane, S.Pri Noir Et Wallen

Paris, le 24 septembre 2018, Hip Hop Symphonique #3 Avec Dosseh, Sniper, Sofiane, S.Pri Noir et Wallen Le 31 octobre 2018 à l’Auditorium de Radio France Mouv’, l’Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France et l’Adami présentent la troisième création de HIP HOP SYMPHONIQUE. Cinq artistes emblématiques de la scène française sont réunis pour un concert unique mêlant hip-hop et musique symphonique, qui se tiendra le mercredi 31 octobre à 20h30 à l’Auditorium de Radio France, avec l'Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France placé sous la direction de Dylan Corlay, le live band The Ice Kream, sous la direction artistique d’Issam Krimi. Hip Hop Symphonique, c’est : l’Auditorium de Radio France complet en moins de trois minutes, plus de soixante musiciens sur scène, une représentation au festival Jazz à Vienne ou encore une version télévisée diffusée sur France Télévision. Les deux premières éditions ont rencontré un vif succès auprès d’un large public. Cette très attendue troisième création s’appuiera de nouveau sur la collaboration de musiciens de formation classique, jazz et gospel et d’artistes de hip-hop français. Mouv', la Direction de la Musique et de la Création de Radio France et l'Adami poursuivent leur volonté de faire de Hip Hop Symphonique un symbole de la mixité des genres rap et classique à travers ce vivier d'artistes exceptionnels. © MarOne Les artistes de la troisième édition Dosseh, activiste du rap français depuis 15 ans, son album VIDALO$$A, sorti en juillet dernier, porté par le titre Habitué a rythmé l’été des Français. -

Hip-Hop Is My Passport! Using Hip-Hop and Digital Literacies to Understand Global Citizenship Education

HIP-HOP IS MY PASSPORT! USING HIP-HOP AND DIGITAL LITERACIES TO UNDERSTAND GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP EDUCATION By Akesha Monique Horton A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Curriculum, Teaching and Educational Policy – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT HIP-HOP IS MY PASSPORT! USING HIP-HOP AND DIGITAL LITERACIES TO UNDERSTAND GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP EDUCATION By Akesha Monique Horton Hip-hop has exploded around the world among youth. It is not simply an American source of entertainment; it is a global cultural movement that provides a voice for youth worldwide who have not been able to express their “cultural world” through mainstream media. The emerging field of critical hip-hop pedagogy has produced little empirical research on how youth understand global citizenship. In this increasingly globalized world, this gap in the research is a serious lacuna. My research examines the intersection of hip-hop, global citizenship education and digital literacies in an effort to increase our understanding of how urban youth from two very different urban areas, (Detroit, Michigan, United States and Sydney, New South Wales, Australia) make sense of and construct identities as global citizens. This study is based on the view that engaging urban and marginalized youth with hip-hop and digital literacies is a way to help them develop the practices of critical global citizenship. Using principled assemblage of qualitative methods, I analyze interviews and classroom observations - as well as digital artifacts produced in workshops - to determine how youth define global citizenship, and how socially conscious, global hip-hop contributes to their definition Copyright by AKESHA MONIQUE HORTON 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely grateful for the wisdom and diligence of my dissertation committee: Michigan State University Drs. -

Banlieue Violence in French Rap

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-03-22 Je vis, donc je vois, donc je dis: Banlieue Violence in French Rap Schyler B. Chennault Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons, and the Italian Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Chennault, Schyler B., "Je vis, donc je vois, donc je dis: Banlieue Violence in French Rap" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 834. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/834 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. "JE VIS, DONC JE VOIS, DONC JE DIS." BANLIEUE VIOLENCE IN FRENCH RAP by Schyler Chennault A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MA in French Studies Department of French and Italian Brigham Young University April 2007 ABSTRACT "JE VIS, DONC JE VOIS, DONC JE DIS." BANLIEUE VIOLENCE IN FRENCH RAP Schyler Chennault Department of French and Italian Master's Since its creation over two decades ago, French rap music has evolved to become both wildly popular and highly controversial. It has been the subject of legal debate because of its violent content, and accused of encouraging violent behavior. This thesis explores the French M.C.'s role as representative and reporter of the France's suburbs, la Banlieue, and contains analyses of French rap lyrics to determine the rappers' perception of Banlieue violence. -

Terrorist and Insurgent Teleoperated Sniper Rifles and Machine Guns Robert J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Faculty Publications and Research CGU Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2016 Terrorist and Insurgent Teleoperated Sniper Rifles and Machine Guns Robert J. Bunker Claremont Graduate University Alma Keshavarz Claremont Graduate University Recommended Citation Bunker, R. J. (2016). Terrorist and Insurgent Teleoperated Sniper Rifles and Machine Guns. Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO), 1-40. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WL KNO EDGE NCE ISM SA ER IS E A TE N K N O K C E N N T N I S E S J E N A 3 V H A A N H Z И O E P W O I T E D N E Z I A M I C O N O C C I O T N S H O E L C A I N M Z E N O T Terrorist and Insurgent Teleoperated Sniper Rifles and Machine Guns ROBERT J. BUNKER and ALMA KESHAVARZ August 2016 Open Source, Foreign Perspective, Underconsidered/Understudied Topics The Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is an open source research organization of the U.S. Army. It was founded in 1986 as an innovative program that brought together military specialists and civilian academics to focus on military and security topics derived from unclassified, foreign media. Today FMSO maintains this research tradition of special insight and highly collaborative work by conducting unclassified research on foreign perspectives of defense and security issues that are understudied or unconsidered. -

“FRENCH” CULTURE by David Spieser Maîtrise

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt THE POLITICS OF AESTHETICS: NATION, REGION AND IMMIGRATION IN CONTEMPORARY “FRENCH” CULTURE by David Spieser Maîtrise, English Literature and American Civilization, Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2004 M.A., French Literature, University of Pittsburgh, 2011 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THE KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by David Spieser It was defended on May 26, 2015 and approved by Dr. Giuseppina Mecchia, Associate Professor of French, Department of French and Italian Dr. Neil Doshi, Assistant Professor of French, Department of French and Italian Dr. David Pettersen, Assistant Professor of French, Department of French and Italian Dr. Susan Andrade, Associate Professor of English, Department of English ii THE POLITICS OF AESTHETICS: NATION, REGION AND IMMIGRATION IN CONTEMPORARY “FRENCH” CULTURE David Spieser, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 This dissertation examines the tensions at work in contemporary French cultural politics between, on the one hand, homogenizing/assimilating hegemonic tendencies and, on the other hand, performances of heterogeneity/disharmony especially in literature but also in other artistic forms such as music. “Regional literature/culture” and “banlieue (ghetto) literature/culture” are studied as two major phenomena that performatively go against France’s “state monolingualism,” here understood as much as a “one-language policy” as the enforcement of “one discourse about Frenchness” (mono-logos).