Short-Term Difference in Mood with Sibutramine Versus Placebo in Obese Patients with and Without Depression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DART-MS/MS Screening for the Determination of 1,3- Dimethylamylamine and Undeclared Stimulants in Seized Dietary Supplements from Brazil

Forensic Chemistry 8 (2018) 134–145 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forensic Chemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/forc DART-MS/MS screening for the determination of 1,3- dimethylamylamine and undeclared stimulants in seized dietary supplements from Brazil Maíra Kerpel dos Santos a, Emily Gleco b, J. Tyler Davidson b, Glen P. Jackson b, Renata Pereira Limberger a, ⇑ Luis E. Arroyo b, a Graduate Program of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil b Department of Forensic & Investigative Science, West Virginia University, USA article info abstract Article history: 1,3-dimethylamylamine (DMAA) is an alkylamine with stimulating properties that has been used pre- Received 15 December 2017 dominantly as an additive in dietary supplements. DMAA is mostly consumed by professional athletes, Received in revised form 14 March 2018 and several doping cases reported since 2008 led to its prohibition by the World Anti-Doping Agency Accepted 18 March 2018 (WADA) in 2010. Adverse effects have indicated DMAA toxicity, and there is few data regarding its safety, Available online 22 March 2018 so it was banned by regulatory agencies from Brazil and the United States. Ambient ionization methods such as Direct Analysis in Real Time Tandem Mass Spectrometry (DART-MS/MS) are an alternative for Keywords: dietary supplements analysis, because they enable the analysis of samples at atmospheric pressure in 1,3-dimethylamylamine a very short time and with only minimal sample preparation. Therefore, the aim of this work was to DART-MS/MS Dietary supplements develop a methodology by DART-MS/MS to detect the presence of DMAA, ephedrine, synephrine, caffeine, Stimulants sibutramine, and methylphenidate in 108 dietary supplements seized by the Brazilian Federal Police Adulterants (BFP). -

Sibutramine Hydrochloride Monohydrate) Capsule CS-IV

MERIDIA - sibutramine hydrochloride capsule ---------- MERIDIA® (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) Capsule CS-IV DESCRIPTION MERIDIA® (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) is an orally administered agent for the treatment of obesity. Chemically, the active ingredient is a racemic mixture of the (+) and (-) enantiomers of cyclobutanemethanamine, 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-N,N-dimethyl-α-(2-methylpropyl)-, hydrochloride, monohydrate, and has an empirical formula of C17H29Cl2NO. Its molecular weight is 334.33. The structural formula is shown below: Sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate is a white to cream crystalline powder with a solubility of 2.9 mg/mL in pH 5.2 water. Its octanol: water partition coefficient is 30.9 at pH 5.0. Each MERIDIA capsule contains 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg of sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate. It also contains as inactive ingredients: lactose monohydrate, NF; microcrystalline cellulose, NF; colloidal silicon dioxide, NF; and magnesium stearate, NF in a hard-gelatin capsule [which contains titanium dioxide, USP; gelatin; FD&C Blue No. 2 (5- and 10-mg capsules only); D&C Yellow No. 10 (5- and 15-mg capsules only), and other inactive ingredients]. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mode of Action Sibutramine produces its therapeutic effects by norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine reuptake inhibition. Sibutramine and its major pharmacologically active metabolites (M1 and M2) do not act via release of monoamines. Pharmacodynamics Sibutramine exerts its pharmacological actions predominantly via its secondary (M1) and primary (M2) amine metabolites. The parent compound, sibutramine, is a potent inhibitor of serotonin (5- hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) and norepinephrine reuptake in vivo, but not in vitro. However, metabolites M1 and M2 inhibit the reuptake of these neurotransmitters both in vitro and in vivo. -

Phenylmorpholines and Analogues Thereof Phenylmorpholine Und Analoge Davon Phenylmorpholines Et Analogues De Celles-Ci

(19) TZZ __T (11) EP 2 571 858 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: C07D 265/30 (2006.01) A61K 31/5375 (2006.01) 20.06.2018 Bulletin 2018/25 A61P 25/24 (2006.01) A61P 25/16 (2006.01) A61P 25/18 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 11723158.9 (86) International application number: (22) Date of filing: 20.05.2011 PCT/US2011/037361 (87) International publication number: WO 2011/146850 (24.11.2011 Gazette 2011/47) (54) PHENYLMORPHOLINES AND ANALOGUES THEREOF PHENYLMORPHOLINE UND ANALOGE DAVON PHENYLMORPHOLINES ET ANALOGUES DE CELLES-CI (84) Designated Contracting States: • DECKER, Ann Marie AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB Durham, North Carolina 27713 (US) GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR (74) Representative: Hoeger, Stellrecht & Partner Patentanwälte mbB (30) Priority: 21.05.2010 US 347259 P Uhlandstrasse 14c 70182 Stuttgart (DE) (43) Date of publication of application: 27.03.2013 Bulletin 2013/13 (56) References cited: WO-A1-2004/052372 WO-A1-2008/026046 (73) Proprietors: WO-A1-2008/087512 DE-B- 1 135 464 • Research Triangle Institute FR-A- 1 397 563 GB-A- 883 220 Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 GB-A- 899 386 US-A1- 2005 267 096 (US) • United States of America, as represented by • R.A. GLENNON ET AL.: "Beta-Oxygenated The Secretary, Department of Health and Human Analogues of the 5-HT2A Serotonin Receptor Services Agonist Bethesda, Maryland 20892-7660 (US) 1-(4-Bromo-2,5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-aminopro pane", JOURNAL OF MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY, (72) Inventors: vol. -

124.210 Schedule IV — Substances Included. 1

1 CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES, §124.210 124.210 Schedule IV — substances included. 1. Schedule IV shall consist of the drugs and other substances, by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or brand name designated, listed in this section. 2. Narcotic drugs. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation containing any of the following narcotic drugs, or their salts calculated as the free anhydrous base or alkaloid, in limited quantities as set forth below: a. Not more than one milligram of difenoxin and not less than twenty-five micrograms of atropine sulfate per dosage unit. b. Dextropropoxyphene (alpha-(+)-4-dimethylamino-1,2-diphenyl-3-methyl-2- propionoxybutane). c. 2-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol, its salts, optical and geometric isomers and salts of these isomers (including tramadol). 3. Depressants. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances, including its salts, isomers, and salts of isomers whenever the existence of such salts, isomers, and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation: a. Alprazolam. b. Barbital. c. Bromazepam. d. Camazepam. e. Carisoprodol. f. Chloral betaine. g. Chloral hydrate. h. Chlordiazepoxide. i. Clobazam. j. Clonazepam. k. Clorazepate. l. Clotiazepam. m. Cloxazolam. n. Delorazepam. o. Diazepam. p. Dichloralphenazone. q. Estazolam. r. Ethchlorvynol. s. Ethinamate. t. Ethyl Loflazepate. u. Fludiazepam. v. Flunitrazepam. w. Flurazepam. x. Halazepam. y. Haloxazolam. z. Ketazolam. aa. Loprazolam. ab. Lorazepam. ac. Lormetazepam. ad. Mebutamate. ae. Medazepam. af. Meprobamate. ag. Methohexital. ah. Methylphenobarbital (mephobarbital). -

Weight Loss Products Adulterated with Sibutramine: a Focused Review of Associated Risks

Central Journal of Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity Review Article *Corresponding author Oberholzer HM, Department of Anatomy, University Weight Loss Products of Pretoria, South Africa, Tel: +27123192533; Email: Submitted: 24 October 2014 Adulterated with Sibutramine: Accepted: 18 November 2014 Published: 20 November 2014 ISSN: 2333-6692 A Focused Review of Associated Copyright © 2014 Oberholzer et al. Risks OPEN ACCESS HM Oberholzer*, MJ Bester, C van der Schoor and C Venter Keywords Department of Anatomy, University of Pretoria, South Africa • Sibutramine • Weight loss • Adverse effects Abstract • Herbal medicine Obesity has been classified as a major worldwide epidemic and associated co- morbidities are Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and several inflammatory disorders. Weight loss drugs in conjunction with diet modification and exercise can reduce co-morbidity risk. Weight loss herbal medicine (WLHM) is perceived by obese and overweight patients as well as those that are not overweight as a natural safe way to lose weight. The wide availability of WLHM, especially through the internet, is of concern as it has been found that many of these products are adulterated with weight loss drugs. Sibutramine is the most commonly found adulterant in WLHM. This paper reviews the literature on the pharmacological and adverse effects of sibutramine, as well as the risk associated with the undisclosed adulteration of WLHM with sibutramine. Sibutramine is a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor that was found to effectively reduce weight but due to reported adverse effects and the death of several patients it was banned. Non-disclosure of this drug as a WLHM ingredient has resulted in an increase in reported serious adverse events. -

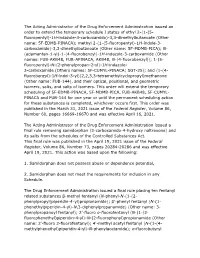

Removing Samidorphan from Schedule II

The Acting Administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration issued an order to extend the temporary schedule I status of ethyl 2-(1-(5- fluoropentyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamido)-3,3-dimethylbutanoate (Other name: 5F-EDMB-PINACA); methyl 2-(1-(5-fluoropentyl)-1H-indole-3- carboxamido)-3,3-dimethylbutanoate (Other name: 5F-MDMB-PICA); N- (adamantan-1-yl)-1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-1H-indazole-3-carboxamide (Other names: FUB-AKB48, FUB-APINACA, AKB48, N-(4-fluorobenzyl)); 1-(5- fluoropentyl)-N-(2-phenylpropan-2-yl)-1H-indazole- 3-carboxamide (Others names: 5F-CUMYL-PINACA; SGT-25); and (1-(4- fluorobenzyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)(2,2,3,3-tetramethylcyclopropyl)methanone (Other name: FUB-144), and their optical, positional, and geometric isomers, salts, and salts of isomers. This order will extend the temporary scheduling of 5F-EDMB-PINACA, 5F-MDMB-PICA, FUB-AKB48, 5F-CUMYL- PINACA and FUB-144 for one year or until the permanent scheduling action for these substances is completed, whichever occurs first. This order was published in the March 31, 2021 issue of the Federal Register, Volume 86, Number 60, pages 16669-16670 and was effective April 16, 2021. The Acting Administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration issued a final rule removing samidorphan (3-carboxamido-4-hydroxy naltrexone) and its salts from the schedules of the Controlled Substances Act. This final rule was published in the April 19, 2021 issue of the Federal Register, Volume 86, Number 73, pages 20284-20286 and was effective April 19, 2021. This action was based upon the following: 1. Samidorphan does not possess abuse or dependence potential, 2. -

Desvenlafaxine Drug Assessment Pristiq® in Major Depressive Report Disorder in Adults @DTB Navarre.Es More Cost for Less

03 2015 DESVENLAFAXINE DRUG ASSESSMENT Pristiq® in major depressive REPORT www.dtb.navarra.es disorder in adults @DTB_Navarre.es More cost for less... ABSTRACT Desvenlafaxine is an active me- tabolite of venlafaxine. Indications1 In the study against escitalopram4 flexible Treatment of major depressive disorder doses of desvenlafaxine were used (100 and In three placebo-controlled 200 mg daily) in postmenopausal women. No trials, the results on the reduc- 1 Mechanism of action advantage of desvenlafaxine over escitalopram tion in HAM-D17 score were not This is an active metabolite of venlafaxine, that was found. consistent. inhibits the reuptake of serotonine and nora- There is only one long-term study16 that eva- dernaline. Its bioavailability reaches up to 80% luated relapse prevention. Patients responding The most common adverse while elimination occurs without alteration after 8 weeks of treatment with desvenlafaxine effects are of gastrointestinal through the urine (45%) and metabolism by 50 mg daily and with a stable response up to origin or sleep disorders. There glucurono conjugation (19%). week 20 were randomized either to placebo or are no available long-term safe- desvenlafaxine 50 mg daily for 6 months. The ty data. Dosage and administration1 endpoint was time to relapse (defined as HAM- The recommended dose is 50 mg daily. The ta- D17 score ≥16), treatment withdrawal due to In the only head-to-head trial blets are swallowed wholly, with liquid with or unsatisfactory response, hospital admission carried out in post-menopause without food and at the same time. The increa- due to depression, suicide attempt or suicide. women, desvenlafaxine at high se in doses should be gradual and up to a maxi- Time to relapse was significantly lower in the doses did not show superiority mum of 200 mg daily and at intervals of at least case of placebo compared to desvenlafaxine versus escitalopram. -

Prescription Medications: Misuse, Abuse, Dependence, and Addiction

Substance Abuse Treatment May 2006 Volume 5 Issue 2 ADVISORYNews for the Treatment Field Prescription Medications: Misuse, Abuse, Dependence, and Addiction How serious are prescription Older adults are particularly vulnerable to misuse and medication use problems? abuse of prescription medications. Persons ages 65 and older make up only 13 percent of the population but Development and increased availability of prescription account for one-third of all medications prescribed,3 drugs have significantly improved treatment of pain, and many of these prescriptions are for psychoactive mental disorders, anxiety, and other conditions. Millions medications with high abuse and addiction liability.4 of Americans use prescription medications safely and Data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health responsibly. However, increased availability and vari- indicate that nonmedical use of prescription medications ety of medications with psychoactive effects (see Table was the second most common form of substance abuse 1) have contributed to prescription misuse, abuse, among adults older than 55.5 dependence, and addiction. In 2004,1 the number of Americans reporting abuse2 of prescription medications Use of prescription medications in ways other than was higher than the combined total of those reporting prescribed can have a variety of adverse health conse- abuse of cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, and heroin. quences, including overdose, toxic reactions, and serious More than 14.5 million persons reported having used drug interactions leading to life-threatening conditions, prescription medications nonmedically within the past such as respiratory depression, hypertension or hypoten- year. Of this 14.5 million, more than 2 million were sion, seizures, cardiovascular collapse, and death.6 between ages 12 and 17. -

Sibutramine Hydrochloride Monohydrate Capsule ------MERIDIA® (Sibutramine Hydrochloride Monohydrate) Capsules CS-IV

MERIDIA - sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate capsule ---------- MERIDIA® (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) Capsules CS-IV DESCRIPTION MERIDIA® (sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate) is an orally administered agent for the treatment of obesity. Chemically, the active ingredient is a racemic mixture of the (+) and (-) enantiomers of cyclobutanemethanamine, 1-(4-chlorophenyl)-N,N-dimethyl-α (2-methylpropyl)-, hydrochloride, monohydrate, and has an empirical formula of C17H29Cl2NO. Its molecular weight is 334.33. The structural formula is shown below: Sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate is a white to cream crystalline powder with a solubility of 2.9 mg/mL in pH 5.2 water. Its octanol: water partition coefficient is 30.9 at pH 5.0. Each MERIDIA capsule contains 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg of sibutramine hydrochloride monohydrate. It also contains as inactive ingredients: lactose monohydrate, NF; microcrystalline cellulose, NF; colloidal silicon dioxide, NF; and magnesium stearate, NF in a hard-gelatin capsule [which contains titanium dioxide, USP; gelatin; FD&C Blue No. 2 (5- and 10-mg capsules only); D&C Yellow No. 10 (5- and 15-mg capsules only), and other inactive ingredients]. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Mode of Action Sibutramine produces its therapeutic effects by norepinephrine, serotonin and dopamine reuptake inhibition. Sibutramine and its major pharmacologically active metabolites (M1 and M2) do not act via release of monoamines. Pharmacodynamics Sibutramine exerts its pharmacological actions predominantly via its secondary (M1) and primary (M2) amine metabolites. The parent compound, sibutramine, is a potent inhibitor of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) and norepinephrine reuptake in vivo, but not in vitro. However, metabolites M1 and M2 inhibit the reuptake of these neurotransmitters both in vitro and in vivo. -

A Weighted and Integrated Drug-Target Interactome

Huang et al. BMC Systems Biology 2015, 9(Suppl 4):S2 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1752-0509/9/S4/S2 RESEARCH Open Access A weighted and integrated drug-target interactome: drug repurposing for schizophrenia as a use case Liang-Chin Huang1, Ergin Soysal1, W Jim Zheng1, Zhongming Zhao2, Hua Xu1*, Jingchun Sun1* From The International Conference on Intelligent Biology and Medicine (ICIBM) 2014 San Antonio, TX, USA. 04-06 December 2014 Abstract Background: Computational pharmacology can uniquely address some issues in the process of drug development by providing a macroscopic view and a deeper understanding of drug action. Specifically, network-assisted approach is promising for the inference of drug repurposing. However, the drug-target associations coming from different sources and various assays have much noise, leading to an inflation of the inference errors. To reduce the inference errors, it is necessary and critical to create a comprehensive and weighted data set of drug-target associations. Results: In this study, we created a weighted and integrated drug-target interactome (WinDTome) to provide a comprehensive resource of drug-target associations for computational pharmacology. We first collected drug-target interactions from six commonly used drug-target centered data sources including DrugBank, KEGG, TTD, MATADOR, PDSP Ki Database, and BindingDB. Then, we employed the record linkage method to normalize drugs and targets to the unique identifiers by utilizing the public data sources including PubChem, Entrez Gene, and UniProt. To assess the reliability of the drug-target associations, we assigned two scores (Score_S and Score_R) to each drug-target association based on their data sources and publication references. -

DRUGS POTENTIALLY AFFECTING MIBG UPTAKE Rev. 26 Oct 2009

DRUGS POTENTIALLY AFFECTING MIBG UPTAKE rev. 26 Oct 2009 EXCLUDED MEDICATIONS DUE TO DRUG INTERACTIONS WITH ULTRATRACE I-131-MIBG Drug Class Generic Drug Name Within Class Branded Name Checked Cocaine Cocaine □ Dexmethylphenidate Focalin, Focalin XR □ CNS Stimulants (Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor) Methylphenidate Concerta, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Methylin ER, Ritalin, Ritalin LA, □ Ritalin-SR, Daytrana benzphetamine Didrex □ Diethylpropion Tenuate, Tenuate Dospan □ Phendimetrazine Adipost, Anorex-SR, Appecon, Bontril PDM, Bontril Slow Release, Melfiat, Obezine, CNS Stimulants (Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor) □ Phendiet, Plegine, Prelu-2, Statobex Phenteramine Adipex-P, Ionamin, Obenix, Oby-Cap, Teramine, Zantryl □ Sibutramine Meridia □ Isocarboxazid Marplan □ Linezolid Zyvox □ Phenelzine Nardil □ Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors selegiline (MAOa at doses > 15 mg qd) Eldepryl, Zelapar, Carbex, Atapryl, Jumex, Selgene, Emsam □ Tranylcypromine Parnate □ Reserpine Generic only. No brands available. Central Monoamine Depleting Agent □ labetolol Non-select Beta Adrenergic Blocking Agents Normodyne, Trandate □ Opiod Analagesic Tramadol Ultram, Ultram ER □ Pseudoephedrine Chlor Trimeton Nasal Decongestant, Contac Cold, Drixoral Decongestant Non- Drowsy, Elixsure Decongestant, Entex, Genaphed, Kid Kare Drops, Nasofed, Sympathomimetics : Direct Alpha 1 Agonist (found in cough/cold preps) Seudotabs, Silfedrine, Sudafed, Sudodrin, SudoGest, Suphedrin, Triaminic Softchews □ Allergy Congestion, Unifed amphetamine (various -

PAPER How Does Sibutramine Work?

International Journal of Obesity (2001) 25, Suppl 4, S8–S11 ß 2001 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0307–0565/01 $15.00 www.nature.com/ijo PAPER How does sibutramine work? MEJ Lean1* 1Department of Human Nutrition, University of Glasgow, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, Glasgow, UK Sibutramine offers three types of benefit in weight management: by enhancing weight loss, by improving weight maintenance and by reducing the comorbidities of obesity. The clinical effects of sibutramine are explained through its known mode of action as a serotonin (5-HT) and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). This dual mechanism of action results in two synergistic physiological effects — a reduction in energy intake and an increase in energy expenditure, which combine to promote and maintain weight loss. International Journal of Obesity (2001) 25, Suppl 4, S8 – S11. Keywords: sibutramine; serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI); energy intake; energy expenditure; weight loss Introduction a 1 y, family practitioner study reported that daily sibutra- Sibutramine is a novel compound which establishes a new mine treatment was associated with significant enhance- class of drug for weight management. When administered ment of satiety (P < 0.01), a reduction in hunger scores daily as part of a weight management programme that (P < 0.001), and reduced cravings for sweet foodstuffs includes diet and exercise, sibutramine allows patients to (P < 0.05) and for carbohydrates (P < 0.01).2 lose weight and to maintain energy balance at a lower body A study by Chapelot et al designed to assess energy intake weight. over a 24 h period found that sibutramine treatment could The weight loss induced by sibutramine is achieved by significantly (P < 0.001) reduce total daily energy intake two complementary physiological effects.