Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report Fy 2016

PHILLIPS BROOKS HOUSE ASSOCIATION “E ve ANNUAL REPORT FY 2016 phillips brooks house association “Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.” -Robert F. Kennedy 2 | PBHA ANNUAL REPORT Dear PBHA Supporters, Phillips Brooks House Association’s 2015 was a truly remark- able year and one that illustrates, perhaps more than ever, the power and impact of what we can accomplish together. This year we were so proud to support the creation and opening of Y2Y (Youth to Youth) Harvard Square, a youth shelter which, thanks to the leadership of alumni Sam Green- berg and Sarah Rosenkrantz, is a powerful example of how we can address some of society’s greatest needs by building partnerships. Y2Y’s opening, which followed an extensive renovation of the space located at First Parish in Cambridge, Unitarian Universalist, united students, homeless youth, residents, business owners, elected officials, and donors in the shared mission of tripling the number of shelter beds dedicated to 18-24 year-olds in Greater Boston. HOPE, the Harvard Organization for Prison Education and Reform, built connections between the prison education programs that have been part of PBHA for more than 60 years and strengthened advocacy efforts addressing abuses in the criminal justice system. With the help of the 2015 Robert Coles Call of Service lecturer and honoree, Black Lives Matter co-founder Alicia Garza, Boston and Cambridge youth joined with Harvard student groups to show their commitment to the ideals of this critical movement. -

March 23, 2009 President Barack Obama President Dmitri Medvedev

March 23, 2009 President Barack Obama President Dmitri Medvedev The White House Ilinka Str, No 23 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW 103132, Moscow Washington, DC 20500 Russia Dear Presidents Obama and Medvedev: For more than 60 years the threat of nuclear annihilation has hung over humanity. We write to you now with great hope that you will seize the opportunity created by your recent elections to address definitively this gravest threat to human survival. The United States and Russia continue to possess enormous arsenals of nuclear weapons originally built to fight the Cold War. If these instruments of mass extermination ever had a purpose, that purpose ended 20 years ago. Yet the US and Russia still have more than 20,000 nuclear warheads. Most dangerously more than 2,300 of them are maintained on ready alert status, mounted on missiles that can be launched in a matter of minutes, destroying cities in each other’s countries a half hour later. A study published in 2002 showed that if only 300 of the weapons in the Russian arsenal attacked targets in American cities, 90 million people would die in the first half hour. A comparable US attack on Russia would produce similar devastation. Furthermore, these attacks would destroy the entire economic, communications, and transportation infrastructure on which the rest of the population depend for survival. In the ensuing months the vast majority of people who survived the initial attacks in both of your countries would die of disease, exposure, and starvation. But the destruction of Russia and the United States is only part of the story. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT FY 2014 who contribute their unique voices, visions, and values to improve PBHA’s services and challenge each other to approach service through different lenses. We further endeavor to build a supportive environment that shares power with our constituents through strong relationships built on mutual respect across identity lines. We are committed to diversity at all levels of PBHA because we genuinely believe that an inclusive organization makes us stronger and more effective in Our Core Values achieving our mission. Maria Dominguez Gray, Class of 1955 Executive Director Growth and Learning. As Jose Magaña ’15, President a student led organization, valuing growth and learning is and must be This year PBHA engaged 1500 ly, passing on the organization better second nature at PBHA. We honor volunteers, serving 10,000 con- than we found it. growth and learning as integral to stituents through 83 programs. The Justice. While the activities building collective leadership, life people and services represented in that take place in PBHA may change skills, and social justice awareness each of the 83 programs are diverse, across the years, they share the in current and future generations of yet there is a common thread that common vision of building a world change agents. We believe that reflec- weaves these experiences together. grounded in economic and social tion and training along with meaning- We are tied together by our mission justice. Justice means that all people ful service are essential to ensuring to build partnerships between student have equal opportunity and rights to both quality impact in our programs and community leaders that address resources, happiness and human dig- and responsible student development. -

Celebrating 40 Years of Rita Allen Foundation Scholars 1 PEOPLE Rita Allen Foundation Scholars: 1976–2016

TABLE OF CONTENTS ORIGINS From the President . 4 Exploration and Discovery: 40 Years of the Rita Allen Foundation Scholars Program . .5 Unexpected Connections: A Conversation with Arnold Levine . .6 SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE Pioneering Pain Researcher Invests in Next Generation of Scholars: A Conversation with Kathleen Foley (1978) . .10 Douglas Fearon: Attacking Disease with Insights . .12 Jeffrey Macklis (1991): Making and Mending the Brain’s Machinery . .15 Gregory Hannon (2000): Tools for Tough Questions . .18 Joan Steitz, Carl Nathan (1984) and Charles Gilbert (1986) . 21 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Robert Weinberg (1976): The Genesis of Cancer Genetics . .26 Thomas Jessell (1984): Linking Molecules to Perception and Motion . 29 Titia de Lange (1995): The Complex Puzzle of Chromosome Ends . .32 Andrew Fire (1989): The Resonance of Gene Silencing . 35 Yigong Shi (1999): Illuminating the Cell’s Critical Systems . .37 SCHOLAR PROFILES Tom Maniatis (1978): Mastering Methods and Exploring Molecular Mechanisms . 40 Bruce Stillman (1983): The Foundations of DNA Replication . .43 Luis Villarreal (1983): A Life in Viruses . .46 Gilbert Chu (1988): DNA Dreamer . .49 Jon Levine (1988): A Passion for Deciphering Pain . 52 Susan Dymecki (1999): Serotonin Circuit Master . 55 Hao Wu (2002): The Cellular Dimensions of Immunity . .58 Ajay Chawla (2003): Beyond Immunity . 61 Christopher Lima (2003): Structure Meets Function . 64 Laura Johnston (2004): How Life Shapes Up . .67 Senthil Muthuswamy (2004): Tackling Cancer in Three Dimensions . .70 David Sabatini (2004): Fueling Cell Growth . .73 David Tuveson (2004): Decoding a Cryptic Cancer . 76 Hilary Coller (2005): When Cells Sleep . .79 Diana Bautista (2010): An Itch for Knowledge . .82 David Prober (2010): Sleeping Like the Fishes . -

Download a Form, Sign It, and Submit It As a Scan Electronically, Or Mail It Back

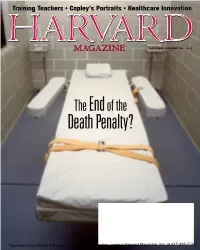

Training Teachers • Copley’s Portraits • Healthcare Innovation NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2016 • $4.95 The End of the Death Penalty? Reprinted from Harvard Magazine. For more information, contact Harvard Magazine, Inc. at 617-495-5746 Hammond Cambridge is now RE/MAX Leading Edge Two Brattle Square | Cambridge, MA 617•497•4400 | CambridgeRealEstate.us CAMBRIDGE—Harvard Square. Two-bedroom SOMERVILLE—Ball Square. Gorgeous, renovated, BELMONT—Belmont Hill. 1936 updated Colonial. corner unit with a wall of south facing windows. 3-bed, 2.5-bath, 3-level, 1,920-square-foot town Period architectural detail. 4 bedroom. 2.5 Private balcony with views of the Charles. 24-hour house. Granite, stainless steel kitchen, 2-zone central bathrooms. C/A, 2-car garage. Private yard with concierge.. .............................................................. $1,200,000 AC, gas heat, W&D in unit, 2-car parking. ...$699,000 mature plantings. ...........................................$1,100,000 BELMONT—Lovely 1920s 9-room Colonial. 4 beds, BELMONT—Oversized, 2000+ sq. ft. house, 5 CAMBRIDGE—Delightful Boston views from private 2 baths. 2011 kitchen and bath. Period details. bedrooms, 2 baths, expansive deeded yard, newer balcony! Sunny and sparkling, 1-bedroom, upgraded Lovely yard, 2-car garage. Near schools and public gas heat and roof, off street parking. Convenient condo. Luxury amenities including 24-hour concierge, transportation. ................................................ $925,000 to train, bus to Harvard, and shops. .....$675,000 gym, pool, garage. -

2016 Annual Report [PDF, 4

1 WHERE WE WORK 2 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 We go. We make house calls. We build health systems. We stay. dear friends, When Partners In Health first responded to the government’s invitation to go to Rwanda, we weren’t thinking much about cancer. We certainly weren’t thinking of Contents it as a disease that we could treat effectively with our most basic infrastructure still in its infancy, in a country without a single oncologist, without diagnostic pathology, and with no available chemotherapy. But from the moment we opened our doors there, in 2005, cancer patients flooded Together in from all over—many of them children with advanced disease. It was an unusual position for PIH to find itself: our organization had grown used to running toward the We . We make . We build . We . go house calls health systems stay 4 fire, and now the fire was running toward us. We had to find a way to treat cancer where few had before. Snapshot One of our early patients was a 7-year-old boy named Sibo Tuyishimire. He’d spent two years feeling hopelessly ill before his family was able to bring him to our A look at our work in Liberia. 14 hospital. PIH doctors soon diagnosed him with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and set him on course to a full, if difficult, recovery. CEO Dr. Gary Gottlieb visits Peru for the site’s 20th anniversary celebration. You + Sibo was kind enough to drop by our Boston office over the holidays. Now, nearly Photo by William Castro Rodríguez a decade in remission, he’s applying to high school here in the U.S. -

Signed, Dan Schwarz, MD MPH, Brigham and Women's Hospital C

Signed, Dan Schwarz, MD MPH, Brigham and Women's Hospital C. Lee, Cohen, MD MBA, Brigham and Women’s Hospital Elizabeth Donnelly, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Peggy Lai, MD MPH, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School Zeinabou Niame Daffe, Mass General Hospital Peter Olds, MD MPH, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School Rod Rahimi, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School Mwanasha Hamuza Merrill, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Mark C Poznansky, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School Ali Abdallah, BDS, Boston University Goldman School of Dental Medicine Yodeline Guillaume, MA, Mass General Hospital Kara Bischoff, MD, UCSF Gustavo E. Velasquez, MD, MPH, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School Inobert Pierre, Health Equity International Roger Shapiro, MD, MPH, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health Marcia B. Goldberg, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital & Harvard Medical School Harvey Simon, Mass General Hospital Asha Clarke, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School Jing Ren, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School Susan, McGirr, MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Kristen Giambusso, MPH, Massachusetts General Hospital Shahin Lockman, MD MSc, Brigham and Women's Hospital, HSPH Jocelyne Jezzini, BDS, CAGS Jessica Haberer, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital Zahir Kanjee, MD, MPH, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Harvard Medical School Nicky Joseph, MD, Candidate Harvard Medical School Ari Johnson, MD, University of California San Francisco | Muso Sriram Shamasunder, MD DTM&H, UCSF HEAL Initiative Vijai Bhola, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical center Andrew R. Lai, MD, MPH, University of California, San Francisco Caitlin Dugdale, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital Bradley Monash, MD, UCSF Sujatha Sankaran, MD , University of California San Francisco Ana Pacheco-Navarro, MD, Stanford University Hospital Madhavi Dandu, MD MPH, UCSF Megha Shankar, MD, Stanford University Sandra J. -

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Annual

COLD SPRING HARBOR LABORATORY ;44 ANNUAL REPORT 1975 Cover: Ruffling lamellipodium and several filopodia extending from a 3T3 mouse fibroblast 15 minutes after plating on a glass substratum. Scanning electron micros- copy; horizontal magnification, 31,500 x. (Photo by G. Albrecht-Buehler) ANNUAL REPORT 1975 COLD SPRING HARBOR LABORATORY COLD SPRING HARBOR, NEW YORK COLD SPRING HARBOR LABORATORY Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, New York OFFICERS OF THE CORPORATION Chairman: Dr. Harry Eagle Treasurer: Angus P. McIntyre Vice Chairman: Edward Pulling Assistant Secretary-Treasurer: Secretary: Mrs. George Lindsay William R. Udry Laboratory Director:Dr.James D. Watson Administrative Director: William R. Udry BOARD OF TRUSTEES INSTITUTIONAL TRUSTEES Albert Einstein College of Medicine Princeton University Dr. Harry Eagle Dr. Bruce Alberts Columbia University The Rockefeller University Dr. Sherman Beychok Dr. Rollin Hotchkiss Duke University Sloan-Kettering Institute Dr. Robert E. Webster Dr. Lewis Thomas Harvard University State University of New York, School of Public Health Stony Brook Dr. Howard Hiatt Dr. Joseph R. Kates Long Island Biological Association University of Wisconsin Edward Pulling Dr. William Dove Massachusetts Institute of Technology Wawepex Society Dr. Herman Eisen Townsend J. Knight New York University Medical Center Dr. Vittorio Defendi INDIVIDUAL TRUSTEES Clarence E. Galston Colton P. Wagner Dr. David P. Jacobus Mrs. Alex M. White Mrs. George N. Lindsay William A. Woodcock Angus P. McIntyre Dr. James D. Watson Walter H. Page Honorary Trustees: Charles Robertson Dr. Alexander Hollaender Arthur D. Trottenberg Dr. H. Bentley Glass Officers and Trustees listed are as of October 31, 1975. DIRECTOR’S REPORT No one can do first-rate science without possessing a deep sense of curiosity. -

What Mad Pursuit BOOKS in the ALFRED P

What Mad Pursuit BOOKS IN THE ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION SERIES Disturbing the Universe by Freeman Dyson Advice to a Young Scientist by Peter Medawar The Youngest Science by Lewis Thomas Haphazard Reality by Hendrik B. G. Casimir In Search of Mind by Jerome Bruner A Slot Machine, a Broken Test Tube by S. E. Luria Enigmas of Chance by Mark Kac Rabi: Scientist and Citizen by John Rigden Alvarez: Adventures of a Physicist by Luis W. Alvarez Making Weapons, Talking Peace by Herbert F. York The Statue Within by François Jacob In Praise of Imperfection by Rita Levi-Montalcini Memoirs of an Unregulated Economist by George J. Stigler Astronomer by Chance by Bernard Lovell THIS BOOK IS PUBLISHED AS PART OF AN ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION PROGRAM What Mad Pursuit A Personal View of Scientific Discovery FRANCIS CRICK Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Crick, Francis, 1916– What mad pursuit. (Alfred P. Sloan Foundation series) Includes index. 1. Crick, Francis, 1916– 2. Biologists—England—Biography. 3. Physicists—England—Biography. I. Title. II. Series. QH31.C85A3 1988 574.19’1’0924 [B] 88–47693 ISBN 0–465–09137–7 (cloth) ISBN-10: 0-465-09138-5 ISBN-13: 978-0-465-09138-6 (paper) eBook ISBN: 9780786725847 Published by BasicBooks, A Member of the Perseus Books Group Copyright © 1988 by Francis Crick Printed in the United States of America Designed by Vincent Torre Experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes. —OSCAR WILDE Preface to the Series THE ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION has for many years had an interest in encouraging public understanding of science. -

Brigham and Women's Hospital and Are Faculty of Harvard Medical School

BRIGHAM AND WOMEN’S HOSPITAL Introduction Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) has a long-standing commitment to improving the health status of Boston residents, with a focus on Boston neighborhoods with disproportionately poor health and social indicators, and documented need for comprehensive health and social services. In addition to being the regional leader in preeminent women's health services, BWH is also one of the nation's leading transplant centers, performing heart, lung, kidney, and heart-lung transplant surgery, as well as, bone marrow transplantation. BWH is nationally recognized for clinical excellence in cardiology and cardiovascular disease, immunology, arthritis and rheumatic disorders, joint replacement, and cancer care through the Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center. Locally, BWH works in collaboration with many community organizations and government agencies to identify and address social determinants of health and to mobilize community resources to improve health status. BWH and its licensed and affiliated health centers provide primary and specialty ambulatory services to culturally diverse groups of people. Through the BWH Center for Community Health and Health Equity, BWH and its health center partners provide a broad array of community service and community health programs, which are designed to have a measurable, positive effect on the health status of underserved populations. Mission Statement The BWH Board of Trustees approved the following community benefit mission statement: Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) is committed to serving the health care needs of persons from diverse communities. The hospital, however, makes a unique commitment to the neighboring residents of Jamaica Plain and Mission Hill, who have some of the most pressing health problems in the state. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The challenge of patient safety and the remaking of American medicine Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/38s4s7v9 Author Van Rite, Eric Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO The Challenge of Patient Safety and the Remaking of American Medicine A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Eric Van Rite Committee in charge: Professor Jeffrey Haydu, Chair Professor Steven Epstein Professor Edwin Hutchins Professor Andrew Lakoff Professor Charles Thorpe 2011 Copyright Eric Van Rite, 2011 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Eric Van Rite is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2011 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………… iii Table of Contents…………………………………………………………… iv List of Tables……………………………………………………………….. v Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….. vi Vita…………………………………………………………………………. ix Abstract…………………………………………………………………….. x CHAPTER 1 – Introduction: The Patient Safety Challenge………………………………… 1 CHAPTER 2 – From Risk to Reform: Changing the Concept of Medical Error…………… 42 CHAPTER 3 – From Tragedy to Advocacy: Patient Stories of Transformation……………. 91 CHAPTER 4 – Making the Case for Patient Safety: Organizational Leaders & Advocacy… -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT Letter from Dimock Leadership

Opening Doors for Generations 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Letter from Dimock Leadership Dear Dimock Family, Generations. Legacy. Family. Over the past year, these words took on great significance. Our physicians, nurses, teachers and clinicians increasingly supported generations of families– the great grandmother who brings her great grandbabies here. The mother whose children attended our Head Start program and who now works here as a teacher. Families come to Dimock because they receive outstanding, personalized care. They develop relationships with our staff that last decades. As much as our patients’ lives are improved by their Dimock care, our employees’ lives are enriched by these relationships. We are blessed to count patients, staff, board members, corporate partners, friends and community partners in our Dimock family. In the pages of our annual report, you will read stories about the generations of Dimock family members who have come through our doors and the dedicated partners whose generosity and vision make our work possible. FY17 (July 1, 2016-June 30, 2017) was a pivotal year for Dimock. We constructed the Dr. Lucy Sewall Center for Acute Treatment Services, which will open in the spring of The People. The Purpose. 2018. This expansion will provide life-saving inpatient detoxification to more than 4,000 men and women annually. We advanced our innovative model of integrated care, Dimock Makes a Difference Every Day providing hundreds of children and teens with behavioral health support within the walls of our health center. And we increased access to healthcare for more than 400 children from our educational programs and residential homes.