Redalyc.THE PORTUGUESE TAX SYSTEM: COMPLEXITY and ENFORCEABILITY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note on Taxation System

Note on Taxation system Introduction Today an important problem against each government is that how to get income temporarily by debt also, but they have to return it after some time. Some government income is received from government enterprises, administrative and judicial tasks and other such sources, but a big part of government income is received from taxation. Taxes: - Taxes are those compulsory payments which are used without any such hope towards government by tax payers that they will get direct benefit in return of them. According to Prof. Seligman, ‘’ Tax is that compulsory contribution given to Government by individuals which is paid in the payment of expenses in all general favours and no special benefit is given in lieu of that.’’ According to Trussing, ‘’The special thing is that in regard of tax in comparison to all amounts taken by government, quid pro quo is not found directly between taxpayer and government administration in it.’’ Characteristics of a Tax It is clear by above mentioned definitions that some specialties are found in tax which are as follows: - (1) Compulsory Contribution—Tax is a contribution given to state by people living within the premises of country due to residence and property etc. or by citizens and this contribution is given for general use only. Though it is a compulsory contribution, therefore, no individual can deny from the payment of tax. For example, no person can say that he is not getting benefit from some services provided by that state or he didn’t get the right to vote, therefore, he is not bound to pay tax. -

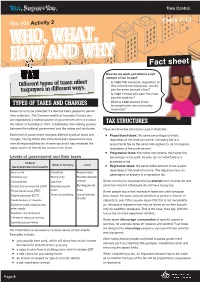

WHO, WHAT, HOW and WHY Fact Sheet

Ta x , Super+You. Take Control. Years 7-12 Tax 101 Activity 2 WHO, WHAT, HOW AND WHY Fact sheet How do we work out what is a fair amount of tax to pay? • Is it fair that everyone, regardless of Different types of taxes affect their income and expenses, should taxpayers in different ways. pay the same amount of tax? • Is it fair if those who earn the most pay the most tax? • What is a fair amount of tax TYPES OF TAXES AND CHARGES for people who use community resources? Taxes can only be collected if a law has been passed to permit their collection. The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act established a federal system of government when it created TAX STRUCTURES the nation of Australia in 1901. It distributes law-making powers between the national government and the states and territories. There are three tax structures used in Australia: Each level of government imposes different types of taxes and Proportional taxes: the same percentage is levied, charges. During World War II the Australian Government took regardless of the level of income. Company tax is a over all responsibilities for income tax and it has remained the proportional tax as the same rate applies for all companies, major source of federal tax revenue ever since. regardless of the profit earned. Progressive taxes: the higher the income, the higher the Levels of government and their taxes percentage of tax paid. Income tax for individuals is a Federal progressive tax. State or territory Local (Australian/Commonwealth) Regressive taxes: the same dollar amount of tax is paid, regardless of the level of income. -

Charging Drivers by the Pound: the Effects of the UK Vehicle Tax System

Charging Drivers by the Pound The Effects of the UK Vehicle Tax System Davide Cerruti, Anna Alberini, and Joshua Linn MAY 2017 Charging Drivers by the Pound: The Effects of the UK Vehicle Tax System Davide Cerruti, Anna Alberini, and Joshua Linn Abstract Policymakers have been considering vehicle and fuel taxes to reduce transportation greenhouse gas emissions, but there is little evidence on the relative efficacy of these approaches. We examine an annual vehicle registration tax, the Vehicle Excise Duty (VED), which is based on carbon emissions rates. The United Kingdom first adopted the system in 2001 and made substantial changes to it in the following years. Using a highly disaggregated dataset of UK monthly registrations and characteristics of new cars, we estimate the effect of the VED on new vehicle registrations and carbon emissions. The VED increased the adoption of low-emissions vehicles and discouraged the purchase of very polluting vehicles, but it had a small effect on aggregate emissions. Using the empirical estimates, we compare the VED with hypothetical taxes that are proportional either to carbon emissions rates or to carbon emissions. The VED reduces total emissions twice as much as the emissions rate tax but by half as much as the emissions tax. Much of the advantage of the emissions tax arises from adjustments in miles driven, rather than the composition of new car sales. Key Words: CO2 emissions, vehicle registration fees, carbon taxes, vehicle excise duty, UK JEL Codes: H23, Q48, Q54, R48 Contact: [email protected]. Cerruti: postdoctoral researcher, Center for Energy Policy and Economics, ETH Zurich; Alberini: professor, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of Maryland; Linn: senior fellow, Resources for the Future. -

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide

Worldwide Estate and Inheritance Tax Guide 2021 Preface he Worldwide Estate and Inheritance trusts and foundations, settlements, Tax Guide 2021 (WEITG) is succession, statutory and forced heirship, published by the EY Private Client matrimonial regimes, testamentary Services network, which comprises documents and intestacy rules, and estate Tprofessionals from EY member tax treaty partners. The “Inheritance and firms. gift taxes at a glance” table on page 490 The 2021 edition summarizes the gift, highlights inheritance and gift taxes in all estate and inheritance tax systems 44 jurisdictions and territories. and describes wealth transfer planning For the reader’s reference, the names and considerations in 44 jurisdictions and symbols of the foreign currencies that are territories. It is relevant to the owners of mentioned in the guide are listed at the end family businesses and private companies, of the publication. managers of private capital enterprises, This publication should not be regarded executives of multinational companies and as offering a complete explanation of the other entrepreneurial and internationally tax matters referred to and is subject to mobile high-net-worth individuals. changes in the law and other applicable The content is based on information current rules. Local publications of a more detailed as of February 2021, unless otherwise nature are frequently available. Readers indicated in the text of the chapter. are advised to consult their local EY professionals for further information. Tax information The WEITG is published alongside three The chapters in the WEITG provide companion guides on broad-based taxes: information on the taxation of the the Worldwide Corporate Tax Guide, the accumulation and transfer of wealth (e.g., Worldwide Personal Tax and Immigration by gift, trust, bequest or inheritance) in Guide and the Worldwide VAT, GST and each jurisdiction, including sections on Sales Tax Guide. -

Taxes and Government Spending 14 SECTION 1 WHAT ARE TAXES? TEXT SUMMARY Taxes Are Payments That People Are Subject to a Tax

CHAPTER Taxes and Government Spending 14 SECTION 1 WHAT ARE TAXES? TEXT SUMMARY Taxes are payments that people are subject to a tax. It also decides how to required to pay to a local, state, or national structure the tax. The three basic kinds of government. Taxes supply revenue, or tax structures are proportional, progres- income, to provide the goods sive, and regressive. A proportional tax THE BIG IDEA and services that people expect is a tax in which the percentage of income Government collects from government. paid in taxes remains the same for all money to run its The Constitution grants income levels. A progressive tax is one programs through Congress the power to tax and in which the percentage increases at different types also limits the kinds of taxes higher income levels. An example is the of taxes. Congress can impose. Federal individual income tax, a tax on a per- taxes must be for the “common son’s income, which requires people defense and general welfare,” with higher incomes to pay a higher per- must be the same in all states, and may not centage of their incomes in taxes. In a be placed on exports. The Sixteenth regressive tax, the percentage increases Amendment, ratified in 1913, gave Con- at lower income levels. A sales tax, a tax gress the power to levy an income tax. on the value of a good or service being When government creates a tax, it sold, is regressive because higher-income decides on the type of tax base—the people pay a lower proportion of their income, property, good, or service that is incomes on goods and services. -

International Tax Policy for the 21St Century

NFTC1a Volume1_part2Chap1-5.qxd 12/17/01 4:23 PM Page 147 The NFTC Foreign Income Project: International Tax Policy for the 21st Century Part Two Relief of International Double Taxation NFTC1a Volume1_part2Chap1-5.qxd 12/17/01 4:23 PM Page 148 NFTC1a Volume1_part2Chap1-5.qxd 12/17/01 4:23 PM Page 149 Origins of the Foreign Tax Credit Chapter 1 Origins of the Foreign Tax Credit I. Introduction The United States’ current system for taxing international income was creat- ed during the period from 1918 through 1928.1 From the introduction of 149 the income tax (in 1913 for individuals and in 1909 for corporations) until 1918, foreign taxes were deducted in the same way as any other business expense.2 In 1918, the United States enacted the foreign tax credit,3 a unilat- eral step taken fundamentally to redress the unfairness of “double taxation” of foreign-source income. By way of contrast, until the 1940s, the United Kingdom allowed a credit only for foreign taxes paid within the British 1 For further description and analysis of this formative period of U.S. international income tax policy, see Michael J. Graetz & Michael M. O’Hear, The ‘Original Intent’ of U.S. International Taxation, 46 DUKE L.J. 1021, 1026 (1997) [hereinafter “Graetz & O’Hear”]. The material in this chapter is largely taken from this source. 2 The reasoning behind the international tax aspects of the 1913 Act is difficult to discern from the historical sources. One scholar has concluded “it is quite likely that Congress gave little or no thought to the effect of the Revenue Act of 1913 on the foreign income of U.S. -

TAXES and TAX POLICY Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin Et Al.)

Chapter 12 TAXES AND TAX POLICY Principles of Economics in Context (Goodwin et al.) Chapter Summary This chapter starts out with a theory of taxes using the supply-and-demand model. Referring back to the chapter on welfare analysis (Chapter 6), it shows how economists may easily deduce the inefficiency of most taxes, based solely on economic efficiency. Moving then to discuss taxation specifically in the United States, data are presented on the structure of various federal taxes, and their impacts. International tax data are then presented to provide context to the U.S. data. The chapter concludes with a discussion of current tax policy issues. Objectives After reading and reviewing this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Illustrate the impacts of an excise tax on a supply-and-demand graph. 2. Illustrate the welfare impacts of an excise tax, also on a supply-and-demand graph. 3. Explain what is meant by tax progressivity. 4. Discuss the structure of the federal income tax in the United States. 5. Discuss the structure of social insurance taxes in the United States. 6. Briefly discuss the structure of other U.S. taxes (e.g., corporate taxes, state and local taxes). 7. Define recent trends in U.S. tax data. 8. Compare tax data from the United States to data from other countries. 9. Discuss the relationship between taxes and economic growth. 10. Define tax incidence analysis. 11. Discuss the distribution of the U.S. tax burden. Key Term Review excise tax progressive tax regressive tax proportional tax marginal propensity to consume total income taxable income marginal tax rate effective tax rate social insurance taxes estate taxes gift taxes supply-side economics tax incidence analysis Chapter 12 – Taxes and Tax Policy 1 Active Review Questions Fill in the Blank 1. -

Dual Progressive Income Tax (Dpit)

DUAL PROGRESSIVE INCOME TAX (DPIT) IV LAC Tax Policy Forum 3-4 July 2014 Mexico City, Mexico Bert Brys, Senior Tax Economist OECD Centre for Tax Policy and Administration Countries have moved away from (semi-) comprehensive income tax systems…… Comprehensive income tax system – taxes all or most income less deductions (net income) under the same rate schedule. Wage and capital income are taxed at the same rates, usually according to a progressive rate schedule; the value to the taxpayers of the tax allowances increases with income. Typically no integration between corporate and personal level capital income taxes No country implements a full comprehensive income tax system: • Very difficult to tax changes in wealth on accrual (the recent proposal in Chile is very interesting) • Imputed income from owner-occupied housing in often taxed at lower rates • Fringe benefits are typically taxed at lower rates than other labour income • Particular form of savings are usually tax-favoured (e.g. pension savings) Typically results in a very high tax burden on labour and capital income, leading reduced work incentives and saving. Tax-arbitrage behaviour as a result of the many tax expenditures Are comprehensive income tax systems compatible with individual taxation (individual as tax unit) or rather imply that the family is the tax unit? 2 …..towards (semi-) dual income tax systems Dual income tax system – levies a proportional tax rate on all net income (capital, wage and pension income less deductions) combined with progressive rates on gross labour and pension income. This implies that labour income is taxed at higher rates than capital income, and that the value of the tax allowances is independent of the income level. -

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Double Taxation Herwig J

Vanderbilt University Law School Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2003 How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Double Taxation Herwig J. Schlunk Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Herwig J. Schlunk, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Double Taxation, 79 Notre Dame Law Review. 127 (2003) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/441 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law School Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE DOUBLE TAXATION HerwigJ Schlunk* INTRODUCTION In the current U.S. federal income tax regime, some of the in- come generated by economic activity conducted in corporate form is taxed twice: first when it is earned by the corporation and again when it is distributed to the owner of an interest in such corporation. This "double taxation" has long been the subject of scorn, and numerous proposals have been put forward to end it.' Most recently, President George W. Bush loudly joined the chorus of double taxation's detrac- tors. He proclaimed that such taxation is "unfair" and "doesn't make any sense," and proposed legislation-centered on an exclusion of dividends from individual income taxation-that would have been its death knell. 2 I have no particular quarrel with the President's assessment of double taxation as such taxation is currently practiced in the United States. -

Land Value Taxation

Land Value Taxation Standard Note: SN6558 Last updated: 17 November 2014 Author: Antony Seely Business & Transport Section The prospects for introducing a Land Value Tax (LVT) – an annual levy on the ownership of land – have been discussed from time to time over the last few years. Proponents have argued that, in addition to raising funds for the Exchequer, an LVT could also be used to stabilise house prices or to reform local government finance by replacing council tax. A further argument in favour of LVT is that taxing gains from increases in land values would be unlikely to distort incentives and should be economically efficient. First, imposing a charge on land values should not affect the availability of land since land is in fixed supply. Second, increases in land values usually come from external developments – such as the construction of infrastructure (roads, tunnels, rail networks, etc) – which require no effort or expenditure on the part of the land’s owner. Arguably landowners would face a windfall loss as soon as the tax was announced, but the tax should not create any disincentives to buy, develop or use the land in question. However, there are significant difficulties to implementing the tax in practice – principally the need to value land separately from buildings, when most market transactions are for plots of land and the property situated on it. There are also concerns that a tax of this nature would penalise home owners on low incomes, particularly if trends in house prices have meant the value of someone’s home has grown significantly faster than their income.1 To date there have not been any serious attempt to introduce an LVT, although recently there has been a good deal of discussion of the case for an abridged form of this charge: a ‘mansions tax’, charged annually on the value of housing, though only assessed on the most expensive homes. -

Taxing Farmland in the United States (AER-679)

States nent of Agriculture Taxing Farmland in Economic Research Service the United States Agricultural Economic Gene Wunderlich Report Number 679 John Blackledge It's Easy To Order Another Copy! Just dial 1-800-999-6779. Toll free in the United States and Canada. Other areas, please call 1-7Û3-834-0125« Ask for Taxing Farmland in the United States (AER-679). The cost is $9.00 per copy. For non-U.S. addresses (including Canada), add 25 per- cent. Ciiarge your purchase to your Visa or MasterCard. Or send a check (made payable to ERS-NASS) to: ERS-NASS 341 Victory Drive Herndon, VA 22070 We'll fill your order by first-class mail. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) proJiibits dis- crimination in its programs onthe basis of race, color^ national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, and mafital or familial status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Personswith disabilities who require alternative means for communication of pro- gram information (braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact the USDA Office of Communications at (202) 720-5881 (voice) or (202) 720-7808 (TDD). To file a complaint, write the Secretary of Agricurture, U.S. Depart- ment of Agriculture, Washington, DC 20250, or call (202) 720-7327 (voice) or (202) 720-1127 (TDD). USDA is an equal employment op- portunity employer. Taxing Farmland in the United States. By Gene Wunderlich, Resources and Technology Division, Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; and John Blackledge, Bureau of the Census, Agriculture Division. Agricultural Economic Report No. 679. Abstract Conceptually, the ad valorem real property tax should be directly proportional to the value of the real property being taxed. -

CHAPTER ONE Tax Fairness Fundamentals

ONE: TAX FAIRNESS FUNDAMENTALS 1 CHAPTER ONE TAX FAIRNESS FUNDAMENTALS he subjects of every state ought to contribute toward the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities; that is, in proportion to the revenue which they respectively enjoy under the protection of the state . [As Henry Home (Lord Kames) has written, a goal of taxation should be to] ‘remedy inequality of riches as much as possible, by relieving the poor and burdening the rich.’ ” 1 “T — Adam Smith, An Inquiry Into The Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) A fair tax system asks citizens to contribute to the cost of ■ A regressive tax makes middle- and low-income families government services based on their ability to pay. This is a pay a larger share of their incomes in taxes than the rich. venerable idea, as old as the biblical notion that a few pennies ■ A proportional tax takes the same percentage of income from a poor woman’s purse cost her more than many pieces of from everyone, regardless of how much or how little they gold from a rich man’s hoard. In discussing tax fairness, we use earn. the terms regressive, proportional and progressive. As the chart ■ A progressive tax is one in which upper-income families below illustrates: pay a larger share of their incomes in tax than do those with lower incomes. REGRESSIVE TAXES PROPORTIONAL TAXES PROGRESSIVE TAXES POOR u u RICH POOR u tRICH POOR u u RICH 2 THE ITEP GUIDE TO FAIR STATE AND LOCAL TAXES Few people would consider a tax system to be fair if the middle- and low-income families to pay a much greater share poorer you are, the more of your income you pay in taxes.