NZ Airports Association Submission On... Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatial Land Use Strategy - North West Kumeū-Huapai, Riverhead, Redhills North

Spatial Land Use Strategy - North West Kumeū-Huapai, Riverhead, Redhills North Adopted May 2021 Strategic Land Use Framework - North West 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 4 1 Purpose ......................................................................................................................... 7 2 Background ................................................................................................................... 9 3 Strategic context.......................................................................................................... 18 4 Consultation ................................................................................................................ 20 5 Spatial Land Use Strategy for Kumeū-Huapai, Riverhead, and Redhills North ........... 23 6 Next steps ................................................................................................................... 43 Appendix 1 – Unitary Plan legend ...................................................................................... 44 Appendix 2 – Response to feedback report on the draft North West Spatial Land Use Strategy ............................................................................................................................. 46 Appendix 3 – Business land needs assessment ................................................................ 47 Appendix 4 – Constraints maps ........................................................................................ -

Historic Heritage Evaluation Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) Hobsonville Headquarters and Parade Ground (Former)

Historic Heritage Evaluation Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) Hobsonville Headquarters and Parade Ground (former) 135 and 214 Buckley Avenue, Hobsonville Figure 1: RNZAF Headquarters (5 July 2017; Auckland Council) Prepared by Auckland Council Heritage Unit July 2017 1.0 Purpose The purpose of this document is to consider the place located at 135 and 214 Buckley Road, Hobsonville against the criteria for evaluation of historic heritage in the Auckland Unitary Plan (Operative in Part) (AUP). The document has been prepared by Emma Rush, Senior Advisor Special Projects – Heritage; and Rebecca Freeman – Senior Specialist Historic Heritage, Heritage Unit, Auckland Council. It is solely for the use of Auckland Council for the purpose it is intended in accordance with the agreed scope of work. 2.0 Identification 135 Buckley Avenue, Hobsonville (Parade Ground) and 214 Buckley Avenue, Hobsonville (former Site address Headquarters) Legal description 135 Buckley Ave - LOT 11 DP 484575 and Certificate of 214 Buckley Ave - Section 1 SO 490900 Title identifier Road reserve – Lot 15 DP 484575 NZTM grid Headquarters – Northing: 5927369; Easting: reference 1748686 Parade Ground – Northing: 5927360; Easting: 1748666 Ownership 135 Buckley Avenue – Auckland Council 214 Buckley Avenue – Auckland Council Road reserve – Auckland Transport Auckland Unitary 135 Buckley Avenue (Parade Ground) Plan zoning Open Space – Informal Recreation Zone 214 Buckley Avenue (former Headquarters) Residential - Mixed Housing Urban Zone Existing scheduled Hobsonville RNZAF -

AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE February 2017

AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE February 2017 ABOUT THE NEW ZEALAND AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION 2 FOREWORD 3 PART A: AIRPORT MASTER PLAN GUIDE 5 1 INTRODUCTION 6 2 IMPORTANCE OF AIRPORTS 7 3 PURPOSE OF AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING 9 4 REFERENCE DOCUMENTS 13 5 BASIC PLANNING PROCESS 15 6 REGULATORY AND POLICY CONTEXT 20 7 CRITICAL AIRPORT PLANNING PARAMETERS 27 8 STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION AND ENGAGEMENT 46 9 KEY ELEMENTS OF THE PLAN 50 10 CONCLUSION 56 PART B: AIRPORT MASTER PLAN TEMPLATE 57 1 INTRODUCTION 58 2 BACKGROUND INFORMATION 59 C O N T E S 3 AIRPORT MASTER PLAN 64 AIRPORT MASTER PLANNING GOOD PRACTICE GUIDE New Zealand Airports Association | February 2017 ABOUT THE NZ AIRPORTS ASSOCIATION The New Zealand Airports Association (NZ Airports) is the national industry voice for airports in New Zealand. It is a not-for-profit organisation whose members operate 37 airports that span the country and enable the essential air transport links between each region of New Zealand and between New Zealand and the world. NZ Airports purpose is to: Facilitate co-operation, mutual assistance, information exchange and educational opportunities for Members Promote and advise Members on legislation, regulation and associated matters Provide timely information and analysis of all New Zealand and relevant international aviation developments and issues Provide a forum for discussion and decision on matters affecting the ownership and operation of airports and the aviation industry Disseminate advice in relation to the operation and maintenance of airport facilities Act as an advocate for airports and safe efficient aviation. Airport members1 range in size from a few thousand to 17 million passengers per year. -

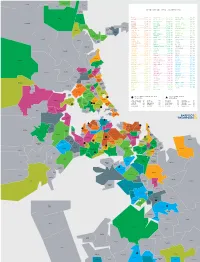

TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach

Warkworth Makarau Waiwera Puhoi TOP MEDIAN SALE PRICE (OCT19—SEP20) Hatfields Beach Wainui EPSOM .............. $1,791,000 HILLSBOROUGH ....... $1,100,000 WATTLE DOWNS ......... $856,750 Orewa PONSONBY ........... $1,775,000 ONE TREE HILL ...... $1,100,000 WARKWORTH ............ $852,500 REMUERA ............ $1,730,000 BLOCKHOUSE BAY ..... $1,097,250 BAYVIEW .............. $850,000 Kaukapakapa GLENDOWIE .......... $1,700,000 GLEN INNES ......... $1,082,500 TE ATATŪ SOUTH ....... $850,000 WESTMERE ........... $1,700,000 EAST TĀMAKI ........ $1,080,000 UNSWORTH HEIGHTS ..... $850,000 Red Beach Army Bay PINEHILL ........... $1,694,000 LYNFIELD ........... $1,050,000 TITIRANGI ............ $843,000 KOHIMARAMA ......... $1,645,500 OREWA .............. $1,050,000 MOUNT WELLINGTON ..... $830,000 Tindalls Silverdale Beach SAINT HELIERS ...... $1,640,000 BIRKENHEAD ......... $1,045,500 HENDERSON ............ $828,000 Gulf Harbour DEVONPORT .......... $1,575,000 WAINUI ............. $1,030,000 BIRKDALE ............. $823,694 Matakatia GREY LYNN .......... $1,492,000 MOUNT ROSKILL ...... $1,015,000 STANMORE BAY ......... $817,500 Stanmore Bay MISSION BAY ........ $1,455,000 PAKURANGA .......... $1,010,000 PAPATOETOE ........... $815,000 Manly SCHNAPPER ROCK ..... $1,453,100 TORBAY ............. $1,001,000 MASSEY ............... $795,000 Waitoki Wade HAURAKI ............ $1,450,000 BOTANY DOWNS ....... $1,000,000 CONIFER GROVE ........ $783,500 Stillwater Heads Arkles MAIRANGI BAY ....... $1,450,000 KARAKA ............. $1,000,000 ALBANY ............... $782,000 Bay POINT CHEVALIER .... $1,450,000 OTEHA .............. $1,000,000 GLENDENE ............. $780,000 GREENLANE .......... $1,429,000 ONEHUNGA ............. $999,000 NEW LYNN ............. $780,000 Okura Bush GREENHITHE ......... $1,425,000 PAKURANGA HEIGHTS .... $985,350 TAKANINI ............. $780,000 SANDRINGHAM ........ $1,385,000 HELENSVILLE .......... $985,000 GULF HARBOUR ......... $778,000 TAKAPUNA ........... $1,356,000 SUNNYNOOK ............ $978,000 MĀNGERE ............. -

North and North-West Auckland Rural Urban Boundary Project

REPORT Auckland Council Geotechnical Desk Study North and North-West Auckland Rural Urban Boundary Project Report prepared for: Auckland Council Report prepared by: Tonkin & Taylor Ltd Distribution: Auckland Council 3 copies Tonkin & Taylor Ltd (FILE) 1 copy August 2013 – Draft V2 T&T Ref: 29129.001 Table of contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 General 1 1.2 Project background 1 1.3 Scope 2 2 Site Descriptions 3 2.1 Kumeu-Whenuapai Investigation Areas 3 2.1.1 Kumeu Huapai 3 2.1.2 Red Hills and Red Hills North 3 2.1.3 Future Business 3 2.1.4 Scott Point 4 2.1.5 Greenfield Investigation Areas 4 2.1.6 Riverhead 4 2.1.7 Brigham Creek 4 2.2 Warkworth Investigation Areas 5 2.2.1 Warkworth North and East 5 2.2.2 Warkworth, Warkworth South and Future Business 5 2.2.3 Hepburn Creek 5 2.3 Silverdale Investigation Areas 6 2.3.1 Wainui East 6 2.3.2 Silverdale West and Silverdale West Business 6 2.3.3 Dairy Flat 6 2.3.4 Okura/Weiti 6 3 Geological Overview 7 3.1 Published geology 7 3.2 Geological units 9 3.2.1 General 9 3.2.2 Alluvium (Holocene) 9 3.2.3 Puketoka Formation and Undifferentiated Tauranga Group Alluvium (Pleistocene) 9 3.2.4 Waitemata Group (Miocene) 9 3.2.5 Undifferentiated Northland Allochthon (Miocene) 10 3.3 Stratigraphy 10 3.3.1 General 10 3.3.2 Kumeu-Whenuapai Investigation Area 11 3.3.3 Warkworth Investigation Area 11 3.3.4 Silverdale Investigation Area 12 3.4 Groundwater 12 3.5 Seismic Subsoil Class 13 3.5.1 Peak ground accelerations 13 4 Geotechnical Hazards 15 4.1 General 15 4.2 Hazard Potential 15 4.3 Slope Instability Potential 15 4.3.1 General 15 4.3.2 Low Slope Instability Potential 16 4.3.3 Medium Slope Instability Potential 17 4.3.4 High Slope Instability Potential 17 4.4 Liquefaction Potential 18 Geotechnical Desk Study North and North-West Auckland Rural Urban Boundary Project Job no. -

Findings of the EPA National Investigation Into Firefighting Foams Containing PFOS

Findings of the EPA national investigation into firefighting foams containing PFOS 4 APRIL 2019 Contents Executive Summary 5 Background 9 PFOS: International and New Zealand regulation 11 Strategy for the investigation 12 Resources 12 Scope of our role 12 Identifying where to investigate 14 Definition of the ‘use’ of foam 15 Definition of compliance 15 Our compliance approach 16 Enforcement actions available to us 16 Carrying out the investigation 18 Collection of evidence 18 Sites where the PFOS in firefighting foam was discovered 18 Observations 19 Compliance and enforcement 21 Outcome 22 Next steps 24 Compliance and enforcement 24 Review of regulatory tools 24 On prosecution 25 Conclusions 25 Appendix 1 Public interest and communications 27 Appendix 2 Sites included in the investigation 29 3 Investigation into firefighting foams containing PFOS | April 2019 4 Investigation into firefighting foams containing PFOS | April 2019 Executive Summary In December 2017, the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) began a national investigation into whether certain firefighting foams were present at airports and other locations in New Zealand. The foams under investigation contain a banned chemical, perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS). This report describes the outcome of this initiative. PFOS foams were restricted in New Zealand in 2006 when they were excluded from the Firefighting Chemicals Group Standard1, meaning PFOS-containing foams could no longer be imported into New Zealand, or be manufactured here. In 2011, an international decision that had recognised PFOS as a persistent organic pollutant2 was written into New Zealand domestic law3. This meant, in addition to the 2006 restriction, any existing products containing PFOS could no longer be used in New Zealand, and strict controls were set to manage their storage and disposal. -

Friday 9 January 1998

10 JANUARY 2008 New Zealand national climate summary – the year 2007 2007: much drier than average in many places, but disastrous floods in Northland. Drought, destructive tornadoes, windstorms, variable temperatures New Zealand’s climate for 2007 was marked by too little rain in many places, and record low rainfalls in some locations. Rainfall during the year was less than 60 percent of normal in parts of Marlborough, Canterbury and Central Otago, with some places recording their driest year on record. Parts of the south and east, and Wellington, recorded one of their sunniest years on record too. The national average temperature was of 12.7°C during 2007 was close to normal. This was a result of some warm months (May being the warmest on record) offset by some cooler months. “Notable climate features in various parts of the country were disastrous floods in Northland with very dry conditions, and drought in the east of the North Island”, says NIWA Principal Scientist Dr Jim Salinger. “As well there was an unprecedented swarm of tornadoes in Taranaki, destructive windstorms in Northland and in eastern New Zealand in October and hot spells. Of the main centres Dunedin was extremely sunny and dry, and it was dry in the other centres.” “The year saw a swing from an El Niño to a La Niña climate pattern. The start of the year was dominated by a weakening El Niño in the equatorial Pacific. From September onwards La Niña conditions had developed in the tropical Pacific, with a noticeable increase in the frequency and strength of the westerlies over New Zealand in October and then a significant drop in windiness from November. -

Part C.10 Landscapes for List of Outstanding Landscapes and the Planning Maps)

APPENDIX 3 Operative Kāpiti Coast District Plan Objectives and Policies Proposed Kāpiti Coast District Plan Objectives and Policies S149(G)3 Key Issues Report – Kāpiti Coast District Council C.1: RESIDENTIAL ZONE C.1 RESIDENTIAL ZONE Over 90% of the district's population live on less than 4% of the land. This land comprises the residential environment. To accommodate this population there has been considerable investment made in buildings, services (water, gas, wastewater disposal) roading and amenity facilities (shops and schools). This represents a significant physical resource which needs to be managed to enable people and communities to meet their needs and to minimise any adverse effects of activities on both the natural and physical environment. The management of this resource can be achieved within the District Plan through controls in the design of subdivision, use and development. The objectives and policies set out below in C.1.1 are intended to address the significant resource management issues identified in B.2. The related subdivision and development issues in B.8 are addressed in C.7. C.1.1 Objectives & Policies OBJECTIVE 1.0 - GENERAL ENSURE THAT THE LOW DENSITY, QUIET CHARACTER OF THE DISTRICT’S RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTS IS MAINTAINED AND THAT ADVERSE EFFECTS ON THE AMENITY VALUES THAT CONSTITUTE THIS CHARACTER AND MAKE THE RESIDENTIAL ENVIRONMENTS SAFE, PLEASANT AND HEALTHY PLACES FOR RESIDENTS ARE AVOIDED, REMEDIED OR MITIGATED. The residential environments within the Kapiti Coast District generally have a low density character, typified by low building heights and density and a high proportion of public and private open space. -

Submission to the Productivity Commission on the Draft Report on Better Urban Planning

SUBMISSION TO THE PRODUCTIVITY COMMISSION ON THE DRAFT REPORT ON BETTER URBAN PLANNING 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 The New Zealand Airports Association ("NZ Airports") welcomes the opportunity to comment on the Productivity Commission's Draft Report on Better Urban Planning ("Draft Report"). 1.2 NZ Airports has submitted on the Resource Legislation Amendment Bill ("RLAB") and presented to the Select Committee on the RLAB, and has also submitted on the Proposed National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity ("NPS-UDC"). Our members have also been closely involved in extensive plan review processes in Auckland and Christchurch. Such participation is costly and time consuming - but necessary, given the important role the planning framework plays in our operations. 1.3 As discussed in our previous submissions, it is fundamental to the development of productive urban centres that residential and business growth does not hinder the effective current or future operation of New Zealand's airports. 1.4 In our view, the Draft Report does not adequately acknowledge the importance of significant infrastructure like airports in the context of urban planning and the need to effectively manage reverse sensitivity effects on such infrastructure. This is reflected in some of the Commission's recommendations which seek to limit notification and appeal rights and introduce the ability to amend zoning without using the Schedule 1 process in the Resource Management Act 1991 ("RMA"). NZ Airports has major concerns with such recommendations as they stand to significantly curtail the ability of infrastructure providers to be involved in planning processes and have their key concerns, such as reverse sensitivity effects, taken into account. -

Regional Brand Toolkit

New Zealand New / 2019 The stories of VERSION 3.0 VERSION Regional Brand Toolkit VERSION 3.0 / 2019 Regional Brand Toolkit The stories of New Zealand Welcome to the third edition of the Regional Brand Toolkit At Air New Zealand I’m pleased to share with you the revised version our core purpose of the Regional Brand Toolkit featuring a number of updates to regions which have undergone a is to supercharge brand refresh, or which have made substantial New Zealand’s success changes to their brand proposition, positioning or right across our great direction over the last year. country – socially, environmentally and We play a key role in stimulating visitor demand, growing visitation to New Zealand year-round economically. This is and encouraging visitors to travel throughout the about making a positive country. It’s therefore important we communicate AIR NEW ZEALAND impact, creating each region’s brand consistently across all our sustainable growth communications channels. and contributing This toolkit has proven to be a valuable tool for to the success of – Air New Zealand’s marketing teams, providing TOOLKIT BRAND REGIONAL New Zealand’s goals. inspiring content and imagery which we use to highlight all the regions which make our beautiful country exceptional. We’re committed to showcasing the diversity of our regions and helping to share each region’s unique story. And we believe we’re well placed to do this through our international schedule timed to connect visitors onto our network of 20 domestic destinations. Thank you to the Regional Tourism Organisations for the content you have provided and for the ongoing work you’re doing to develop strong and distinctive brands for your regions. -

Cape Kidnappers, Hawkes Bay Newzealand.Com

Cape Kidnappers, Hawkes Bay newzealand.com Introduction to New Zealand golf New Zealand is a compact country of two main islands stretching 1600 km/ 990 mi (north to south) and up to 400 km / 250 mi (east to west). With a relatively small population of just over 4.5 million people, there’s plenty of room in this green and spectacular land for fairways and greens. All told, New Zealand has just over work of world-class architects 400 golf courses, spread evenly such as Tom Doak, Robert Trent from one end of the country to Jones Jnr, Jack Nicklaus and the other, and the second highest David Harman who have designed number of courses per capita in at least 12 courses (complete the world. with five-star accommodation and cuisine). The thin coastal topography of the land coupled with its hilly Strategically located near either interior has produced a rich snow capped mountains or legacy of varied courses from isolated coastal stretches (and classical seaside links, to the in some cases both) these more traditional parkland courses locations provide not only further inland. superb natural backdrops for playing golf but the added Over the past 20 years, the bonus of breathtaking scenery. New Zealand golfing landscape has been greatly enhanced by the 2 Lydia Ko Lydia Ko is a New Zealand golfer. She was the world’s top amateur when she turned professional in 2013, and is the youngest ever winner of a professional golf event. “ New Zealand is simply an amazing golf destination. It has some of the best golf courses I have ever played. -

Aog Car Rental Guide.Indd

HERTZ RENTAL CAR CHARGES University of Auckland Note: All insurance claims regardless of excess are subject to Hertz Rental Agreement Terms and Conditions. DAILY RENTAL RATES EXCLUDING GST - SELF INSURED DAYS VEHICLE GROUP 1-3 4-6 7-13 14-20 21-27 28+ Economy B $40.00 $38.00 $37.20 $36.00 $35.20 $34.00 Compact Manual C $44.00 $41.80 $40.92 $39.60 $38.72 $37.40 Compact Auto D $44.00 $41.80 $40.92 $39.60 $38.72 $37.40 Intermediate Auto E $53.00 $50.35 $49.29 $47.70 $46.64 $45.05 Full size Sedan F $59.00 $56.05 $54.87 $53.10 $51.92 $50.15 Premium AWD H $67.00 $63.65 $62.31 $60.30 $58.96 $56.95 Intermediate 4WD J $60.00 $57.00 $55.80 $54.00 $52.80 $51.00 Premium 8 Seater K $82.00 $77.90 $76.26 $73.80 $72.16 $69.70 Premium 4WD M $90.00 $85.50 $83.70 $81.00 $79.20 $76.50 Prestige Auto P $120.00 $114.00 $111.60 $108.00 $105.60 $102.00 12 Seater Van I, X $98.00 $93.10 $91.14 $88.20 $86.24 $83.30 2WD Ute U $80.00 $76.00 $74.40 $72.00 $70.40 $68.00 4WD Ute U4 $90.00 $85.50 $83.70 $81.00 $79.20 $76.50 NEW ZEALAND FLEET GUIDE Passengers Small Suitcase Large Suitcase ECONOMY 4 1 COMPACT MANUAL 4 1 1 Holden Barina Spark Toyota Yaris Toyota Corolla Mazda 3 Manual - EDMR Group B Manual - CDMR Group C COMPACT AUTO 4 1 1 Toyota Corolla Mazda 3 Ford Focus Holden Trax Auto - CDAR Group D INTERMEDIATE 5 1 2 Toyota Camry Ford Mondeo Holden Malibu Auto - IDAR Group E FULL SIZE 5 2 2 PRESTIGE 5 1 2 Holden Commodore VF Ford Falcon XR6 BMW 320i Lexus Hybrid ES300h Auto - FDAR Group F Auto - GDAV Group P Auto - GDAH Group L INTERMEDIATE 4WD 5 2 2 PREMIUM WAGON AWD 5 2 2 Toyota RAV4 Ford Kuga Toyota Highlander Auto - IFAR Group J Auto - PWAR Group H Vehicle models may differ and specifications may vary by location.