Hardware-Enabled Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COUNTERFEIT MEDICINE: Is It Curing China?

COUNTERFEIT MEDICINE: Is It Curing China? NATASHA WONG, ESQ.* I. INTRODUCTION II. OVERVIEW OF CHINA’S PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY III. WHAT IS THE REALITY? A. Lack of Reported Cases B. Sophistication of Counterfeiters IV. SOLVING THE DILEMMA—CHINA’S LEGISLATIVE SOLUTIONS A. Pharmaceutical Administration Law B. Civil and Administrative Penalties C. Criminal Penalties D. Enforcement—Has the Solution Worked? 1. Entry of Organized Crime 2. Military and Police Corruption V. WHY IS THERE A MARKET FOR COUNTERFEIT MEDICATIONS? A. Lack of Consumer Education B. Unaffordable Medication 1. Looking for Alternatives 2. The Added Costs of Manufacturing Medicine 3. Is Social Insurance to Provide Healthcare to More Chinese? 4. Changes to China’s Healthcare System C. Black Market Provides Jobs VI. IMPACT OF COUNTERFEIT MEDICATIONS IN CHINA A. Population Development B. Danger to AIDS Treatments C. Easily Accessible—The Example of Viagra VII. IMPACT OF COUNTERFEIT MEDICINE OUTSIDE OF CHINA A. Presence in Developed Countries 1. Smuggling through Mexico 2. At the Canadian Border B. Internet Facilitates Distribution VIII. CONCLUSION * Natasha Wong is a lawyer from San Diego, California. She is the Executive Director of Chinese Professional Services. She is also serving on the Board of Directors of the Chinese Social Service Center of San Diego and the vice principal of the Chinese School of San Diego. She received her B.A. from the University of California at Berkeley, J.D. from Whittier Law School, and LL.M. from the University of San Diego. Her education includes studies at Shi-Da University, Taiwan, and at Oxford University, England. She would like to thank her husband and parents for their endless patience and support. -

Pill Presses: an Overlooked Threat to American Patients

ILLEGAL PILL PRESSES: AN OVERLOOKED THREAT TO AMERICAN PATIENTS A Joint Project by: national association of Boards of pharmacy, National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators, and THE PARTNERSHIP FOR SAFE MEDICINES March 2019 Executive Summary For less than $500, an individual with ill intent can purchase a pill press and a counterfeit pill mold that allows them to turn cheap, readily available, unregulated ingredients into a six-fi g- ure profi t. Criminals rely upon these pill presses to create dangerous counterfeit medications with toxic substances such as cheaply imported fentanyl (analogues). Their deadly home- made products have reached 46 states in the United States. Of grave concern is the signifi - cant lack of manufacturing control utilized in the making of these counterfeit products. The inexperience of these “garage manufacturers” has killed unsuspecting Americans in 30 states. Counterfeit medications that can kill someone with a single pill are a reality that is increas- ing at an alarming rate. This is a critical health issue that all three of our organizations are urgently striving to stay on top of. How do these criminals get their hands on pill presses? How are they evading customs in- spections? Is possession of these presses illegal and if so, why are more people not charged with it? Recently, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators and The Partnership for Safe Medicines joined together to research the extent of the pill press challenge for law enforcement and other fi rst responders. Key fi ndings include: © March 2019 NABP, NADDI, and PSM ● 2 Illegal Pill Presses: An Overlooked Threat 1. -

Unit-Of-Use Versus Traditional Bulk Packaging

Student Projects PHARMACY PRACTICE Unit-of-Use Versus Traditional Bulk Packaging Tiffany So¹ and Albert Wertheimer, Ph.D.¹: ¹Department of Pharmacy Practice, Temple University School of Pharmacy, Philadelphia, PA Keywords: Unit-of-Use, Bulk Packaging, Adherence, Economic Analysis Abstract Background: The choice between unit-of-use versus traditional bulk packaging in the US has long been a continuous debate for drug manufacturers and pharmacies in order to have the most efficient and safest practices. Understanding the benefits of using unit-of- use packaging over bulk packaging by US drug manufacturers in terms of workflow efficiency, economical costs and medication safety in the pharmacy is sometimes challenging. Methods: A time-saving study comparing the time saved using unit-of-use packaging versus bulk packaging, was examined. Prices between unit-of-use versus bulk packages were compared by using the Red Book: Pharmacy’s Fundamental Reference. Other articles were reviewed on the topics of counterfeiting, safe labeling, and implementation of unit-of-use packaging. Lastly, a cost-saving study was reviewed showing how medication adherence, due to improved packaging, could be cost-effective for patients. Results: When examining time, costs, medication adherence, and counterfeiting arguments, unit-of-use packaging proved to be beneficial for patients in all these terms. Introduction often geared towards hospitals. Therefore, the difference Whether to use unit-of-use versus traditional bulk packaging between these two types of packaging is that unit-of-use is a continuous debate for drug manufacturers and packaging contains multiple doses while unit dose packaging pharmacies in order to have the most efficient and safest contains one dose.5 Bulk packaging contains one type of practices. -

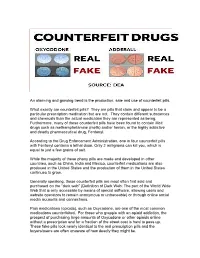

Fake Pills Look Nearly Identical to the Real Prescription Pills and the Buyers/Users Are Often Unaware of How Deadly They Might Be

An alarming and growing trend is the production, sale and use of counterfeit pills. What exactly are counterfeit pills? They are pills that claim and appear to be a particular prescription medication but are not. They contain different substances and chemicals than the actual medication they are represented as being. Furthermore, many of these counterfeit pills have been found to contain illicit drugs such as methamphetamine (meth) and/or heroin, or the highly addictive and deadly pharmaceutical drug, Fentanyl. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, one in four counterfeit pills with Fentanyl contains a lethal dose. Only 2 milligrams can kill you, which is equal to just a few grains of salt. While the majority of these phony pills are made and developed in other countries, such as China, India and Mexico, counterfeit medications are also produced in the United States and the production of them in the United States continues to grow. Generally speaking, these counterfeit pills are most often first sold and purchased on the “dark web” (Definition of Dark Web: The part of the World Wide Web that is only accessible by means of special software, allowing users and website operators to remain anonymous or untraceable) or through online social media accounts and connections. Pain medications (opioids), such as Oxycodone, are one of the most common medications counterfeited. For those who grapple with an opioid addiction, the prospect of purchasing large amounts of Oxycodone or other opioids online without a prescription and for a fraction of the street cost is hard to pass up. These fake pills look nearly identical to the real prescription pills and the buyers/users are often unaware of how deadly they might be. -

Public Awareness and Attitude Towards Counterfeit Medicines in Sudan: a Cross-Sectional Study Wala W

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.20201400; this version posted September 30, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Public Awareness and Attitude towards Counterfeit Medicines in Sudan: A cross-sectional study Wala W. Wagiella1, Shaza W. Shantier2*, Elrasheed A. Gadkariem2 1Department of Pharmacy Practice, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Khartoum, Sudan 2Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Khartoum, Sudan *Correspondance email: [email protected] Abstract Background: Counterfeit medicines (CFMs) are a global problem with significant and well- documented consequences for global health and patient safety, including drug resistance and patient deaths. Reports of counterfeit pharmaceuticals in Africa indicate a wide variety of detrimental effects. Objectives: The aim of the present study was to assess the extent, awareness and attitude of public in Sudan towards CFMs. Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted applying pretested and structured questionnaire. The awareness and attitude were assessed statistically and the association between those and different demographic characteristics was calculated using Fisher exact test and Spearman correlation. Results: A total of 386 participants have enrolled in the study. The majority of the respondents (58%) were found to be aware about the term CFMs with social media mentioned to be the main source. 73% of the respondents considered CFMs of worse quality suggesting getting the medicine from a trustworthy pharmacist in order to avoid buying CFMs. -

Healthtech Report Prevalence of Counterfeit Or Substandard

HealthTech Report April 2014 Prevalence of counterfeit or substandard antibiotics in developing countries Literature review MAILING ADDRESS PO Box 900922 Seattle, WA 98109 USA ADDRESS 2201 Westlake Avenue Suite 200 Seattle, WA, USA TEL: 206.285.3500 FAX: 206.285.6619 www.path.org Support for this project is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of the HealthTech Cooperative Agreement # AID-OAA-A-11-00051. The contents are the responsibility of PATH and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government. ii Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 Objective ......................................................................................................................................... 1 Search methodology ....................................................................................................................... 1 Results ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Limitations ................................................................................................................................... 2 Systematic literature reviews of counterfeit/substandard drugs ............................................... 2 Single‐country and multi‐country studies of counterfeit/substandard -

Role of the Pharmacist in Preventing Distribution of Counterfeit Medications Walter G

Preventing Distribution of Counterfeit Medications (printer-friendly) Page 1 of 6 www.medscape.com Role of the Pharmacist in Preventing Distribution of Counterfeit Medications Walter G. Chambliss, PhD; Wesley A. Carroll, BSPharm; Daniel Kennedy, BSPharm; Donald Levine, DPh; Michael A. Moné, BSPharm, JD; L. Douglas Ried, PhD; Marv Shepherd, PhD; Mukund Yelvigi, MS Posted: 03/06/2012; J Am Pharm Assoc. 2012;52(2):195-199. © 2012 American Pharmacists Association Abstract and Introduction Abstract Objective: To provide an overview of the counterfeit medication problem and recommendations of a joint American Pharmacists Association (APhA) Academy of Pharmaceutical Research and Science and APhA Academy of Pharmacy Practice and Management taskforce. Date sources: SciFinder and PubMed were searched from 1980 to March 2011 using the following keywords: counterfeit drug product, counterfeit medications, drug product authentication, drug product verification, and track-and-trace. Publications, presentations, and websites of organizations that research the counterfeit medication problem in the United States and other countries were reviewed. A representative from the security division of a pharmaceutical manufacturer and a representative from a supplier of anticounterfeiting technologies gave presentations to the taskforce. Summary: The taskforce recommends that pharmacists (1) purchase medications from known, reliable sources; (2) warn patients of the dangers of purchasing medications over the Internet; (3) confirm with distributors that products -

Counterfeit Drugs: Fighting Illegal Supply Chains

COUNTERFEIT DRUGS: FIGHTING ILLEGAL SUPPLY CHAINS HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 27, 2014 Serial No. 113–120 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce energycommerce.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 88–828 WASHINGTON : 2015 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 12:01 Aug 14, 2015 Jkt 037690 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\MY DOCS\HEARINGS 113\113-120 CHRIS COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE FRED UPTON, Michigan Chairman RALPH M. HALL, Texas HENRY A. WAXMAN, California JOE BARTON, Texas Ranking Member Chairman Emeritus JOHN D. DINGELL, Michigan ED WHITFIELD, Kentucky Chairman Emeritus JOHN SHIMKUS, Illinois FRANK PALLONE, JR., New Jersey JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania BOBBY L. RUSH, Illinois GREG WALDEN, Oregon ANNA G. ESHOO, California LEE TERRY, Nebraska ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York MIKE ROGERS, Michigan GENE GREEN, Texas TIM MURPHY, Pennsylvania DIANA DEGETTE, Colorado MICHAEL C. BURGESS, Texas LOIS CAPPS, California MARSHA BLACKBURN, Tennessee MICHAEL F. DOYLE, Pennsylvania Vice Chairman JANICE D. SCHAKOWSKY, Illinois PHIL GINGREY, Georgia JIM MATHESON, Utah STEVE SCALISE, Louisiana G.K. BUTTERFIELD, North Carolina ROBERT E. LATTA, Ohio JOHN BARROW, Georgia CATHY MCMORRIS RODGERS, Washington DORIS O. MATSUI, California GREGG HARPER, Mississippi DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, Virgin Islands LEONARD LANCE, New Jersey KATHY CASTOR, Florida BILL CASSIDY, Louisiana JOHN P. -

Sick Crime: Counterfeit Drugs in the United States

SICK CRIME: COUNTERFEIT DRUGS IN THE UNITED STATES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON CRIMINAL JUSTICE, DRUG POLICY, AND HUMAN RESOURCES OF THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 1, 2005 Serial No. 109–194 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 30–672 PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:41 Dec 15, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\DOCS\30672.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM TOM DAVIS, Virginia, Chairman CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut HENRY A. WAXMAN, California DAN BURTON, Indiana TOM LANTOS, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida MAJOR R. OWENS, New York JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York JOHN L. MICA, Florida PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, Pennsylvania DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois CHRIS CANNON, Utah WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee DIANE E. WATSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland DARRELL E. ISSA, California LINDA T. -

The Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA)

Student Project POLICY Combating Substandard and Counterfeit Medicines by Securing the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain: The Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) of 2013 Phuong Le, PharmD Candidate; Laurie Grund, PharmD Candidate; John Marwa, PharmD Candidate; Wuraola Ojo, MSc, PharmD Candidate; John Otts Jr., PharmD Candidate; and Farhia Arab, PharmD Candidate College of Pharmacy, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN Abstract On November 27, 2013, President Obama signed into law the Drug Quality Security Act (DQSA). Title II of the DQSA, the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), replaces all existing or future state-wide drug track or trace systems with a new federal drug tracing program that uses pedigrees and product identifiers for verification of the drugs being accepted by the buyer. While the full implementation of the DSCSA is projected to take about ten years from its enactment, both the implementation framework and milestones of the new federal tracing program have been carefully laid out. In this essay, we will explore the current state of the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain and the imperatives behind the DSCSA. At the crux of this essay is an analysis of the DSCSA implementation plan, its challenges according to feedback from stakeholders, and its potential effectiveness against the entrance of substandard and counterfeit drugs into the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain. Keywords: Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) Introduction I. Why Now? The Current State of the U.S. Pharmaceutical Since the enactment of the Prescription Drug Marketing Act Supply Chain and the Imperatives to Track and Trace (PDMA) of 1987, the federal and state governments have tried Counterfeit5 and Substandard6 Medicines to combat counterfeit drugs from entering the United States In 2007, U.S. -

Final Report

FINAL REPORT Addressing the Barriers to Effective Monitoring, Reporting and Containment of Spurious/Substandard/Falsely-labelled/ Falsified/Counterfeit Medical Products through Sustainable Multi-stakeholder Collaboration and Community/Consumer-based Interventions A report prepared for the Medicines Transparency Alliance, Philippines Yolanda R. Robles, RPh, PhD Jean Flor C. Casauay, RPh, MS Bryan Paul I. Bulatao, RPh, MS Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................................ 4 GLOSSARY OF ACRONYMS ......................................................................................................................... 5 I. BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................ 7 A. The Global Problem of Counterfeit Medicines ....................................................................................... 8 B. Gaps in the Pharmaceutical Supply Chain ............................................................................................... 9 C. Public Health and Trade Consequences of SSFFC Medicinal Products ..................................... 12 II. RATIONALE / SIGNIFICANCE OF THE STUDY ........................................................................ -

The Crisis in Intellectual Property Protection and China's Role in That Crisis

THE CRISIS IN INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION AND CHINA'S ROLE IN THAT CRISIS Trade Lawyers Advisory Group Terence P. Stewart, Esq. Elizabeth A. Argenti, Esq. Philip A. Butler, Esq. Stewart and Stewart May 2007 Acknowledgements: Section III (An Overview of Enforcement Measures in China and China’s Efforts to Improve Intellectual Property Enforcement) co-authored by David J. Ohrenstein of Trade Lawyers Advisory Group Associate Member, Fontheim International, LLC. Appendix 2 (U.S.- China Trade Flow Statistics) was prepared by Charles W. McMillion, Ph.D. of Trade Lawyers Advisory Group Associate Mem- ber, MBG Information Services Appendix 13 (The Global Publication of U.S. Patent Applications & Select Patent Reform Proposals) was prepared by Pat Choate of Trade Lawyers Advisory Group Associate Member, The Manufacturing Policy Project Additional research and assistance provided by Mirko Czechleba, Patrick J. McDonough, Esq., and Nobutami Shimomoto of Stewart and Stewart Copyright © 2007 by The Trade Lawyers Advisory Group LLC This project is funded by a grant from the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA). SBA’s funding should not be construed as an endorsement of any products, opinions or services. All SBA-funded projects are extended to the public on a nondiscriminatory basis. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. THE CRISIS IN PROTECTING INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS ............................ 1 A. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 B. THE NATURE OF THE CRISIS.............................................................................