COUNTERFEIT MEDICINE: Is It Curing China?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

Ufc 259 Headlined by Three Thrilling World Championship Bouts

UFC 259 HEADLINED BY THREE THRILLING WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP BOUTS Las Vegas – UFC® delivers its most stacked Pay-Per-View event of 2021 so far, headlined by a trio of world championship bouts. Newly crowned UFC light heavyweight championJan Blachowicz makes his first title defense against UFC middleweight champion Israel Adesanya, who aims to become only the fifth fighter to simultaneously hold belts in two UFC weight classes. Two-division titleholder Amanda Nunes puts her UFC featherweight championship on the line against talented striker Megan Anderson. Plus, UFC bantamweight champion Petr Yan looks to take out surging No. 1 contenderAljamain Sterling. UFC® 259: B?ACHOWICZ vs. ADESANYA will take place Saturday, March 6 at UFC APEX in Las Vegas and will stream live on Pay- Per-View, exclusively through ESPN+ in the U.S. at 10 p.m. ET/7 p.m. PT in both English and Spanish. ESPN+ is the exclusive provider of all UFC Pay-Per-View events to fans in the U.S. as part of an agreement announced in 2019. Fans will be able to purchaseUFC ® 259: B?ACHOWICZ vs. ADESANYAonline at ESPNPlus.com/PPV or on the ESPN App on mobile and connected-TV devices. ESPN+ is available as an integrated part of the ESPN App on all major mobile and connected TV devices and platforms, including Amazon Fire, Apple, Android, Chromecast, PS4, Roku, Samsung Smart TVs, X Box One and more. Preliminary fights will air nationally in English on ESPN and in Spanish on ESPN Deportes, as well as being simulcast in both languages on ESPN+ starting at 8 p.m. -

JC Took 3Rd in 1996 Contest

Saturday, August 7, 2021 The Commercial Review Portland, Indiana 47371 www.thecr.com $1 Court asked Fiery fourth to block vaccine mandate IU requires Jay County High COVID shots School band director Kelly Smeltzer (left) for all and percussion students, instructor Mitch Snyder employees (right) celebrate together after the Marching Patriots’ By JESSICA GRESKO Associated Press performance during the WASHINGTON — The preliminaries at Supreme Court is being Friday’s Indiana State asked to block a plan by Fair Band Day contest. Indiana University to JCHS repeated as the require students and Class 3A percussion employees to get vaccinat - champions — it has ed against COVID-19. It's won the award three the first time the high court has been asked to times in the last six weigh in on a vaccine man - contests. The date and comes as some Marching Patriots corporations, states and advanced to the finals cities are also contemplat - and finished fourth, ing or have adopted vac - just 0.013 points cine requirements for behind third place workers or even to dine Winchester. JCHS had indoors. The case is not the first finished third in each time a coronavirus-related of the last four state issue has been before the fair competitions. court. In rulings over the past year the conservative- dominated high court has largely backed religious groups who have chal - lenged restrictions on indoor services during the cononavirus pandemic. The Commercial Review/Ray Cooney In the current case, how - ever, a three-judge federal appeals court panel, Jay County percussion repeats caption victory including two judges appointed by former Presi - dent Donald Trump, was as Marching Patriots finish fourth at state fair one of two lower courts to By RAY COONEY side with Indiana Univer - The Commercial Review sity and allow it to require Everyone knew the Band Day the vaccinations. -

UMBC UGC New Course Request: HIST 386: Hindus, Muslims, and Their Others: Identities in India & Pakistan Amy Froide Froide@U

UMBC UGC New Course Request: HIST 386: Hindus, Muslims, and their Others: Identities in India & Pakistan Date Submitted: 9/4/19 Proposed Effective Date: Spring 2020 Name Email Phone Dept Dept Chair Amy Froide [email protected] 410-455- History or UPD 2033 Other Contact COURSE INFORMATION: Course Number(s) Hindus, Muslims, and their Others: The Construction of Identities in India and Formal Title Pakistan Transcript Title (≤30c) India and Pakistan from 1857-Present Recommended Course Preparation Lower level SS course Prerequisite NOTE: Unless otherwise indicated, a prerequisite is N/A assumed to be passed with a “D” or better. # of Credits Must adhere to the UMBC Credit Hour 3.0 Policy Repeatable for Yes X No additional credit? Max. Total Credits 3.0 This should be equal to the number of credits for courses that cannot be repeated for credit. For courses that may be repeated for credit, enter the maximum total number of credits a student can receive from this course. E.g., enter 6 credits for a 3 credit course that may be taken a second time for credit, but not for a third time. Please note that this does NOT refer to how many times a class may be retaken for a higher grade. Grading Method(s) X Reg (A-F) Audit Pass-Fail PROPOSED CATALOG DESCRIPTION (Approximately 75 words in length. Please use full sentences.): This course explores the complexities of the categories of Hindus, Muslims, and their Others from the mid- 19th century to the present in South Asia (the regions that would become India, Pakistan, and Kashmir). -

Awards Dinner to Honor Reporting in a Year of Crisis

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • March-April 2016 Awards Dinner to Honor Reporting in a Year of Crisis EVENT PREVIEW: April 28 By Chad Bouchard Europe’s refugee crisis and deadly terrorist attacks are in focus in this year’s Dateline magazine, which will be shared at the OPC’s Annual Awards Dinner on April 28. The issue – and the gala event – honors the work of international journalists covering up- Christopher Michel Jonas Fredwall Karlsson Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images heaval in the face of growing threats, Left to right: Kai Ryssdal of Marketplace, David Fanning of PBS FRONTLINE which OPC President Marcus Mabry and Jason Rezaian of The Washington Post. said makes the work of correspon- President’s Award. In a message to press freedom candle in memory of dents harder and ever more essential. Fanning offering the award, Mabry journalists who have died in the line Kai Ryssdal, host and senior edi- praised FRONTLINE and Fanning’s of duty in the past year and in honor of tor of American Public Media’s Mar- “extraordinary, defining” work since those injured, missing and abducted. ketplace, will be our presenter. Rys- the show’s first season in 1983. Fan- The dinner will be held at the Man- sdal joined Marketplace in 2005, and ning retired as executive producer last darin Oriental Hotel on Columbus has hosted the show from China, the year after 33 seasons, and still serves Circle, and begins with a reception at Middle East and across the United States. This year’s 22 award winners at the series’ executive producer at 6:00 p.m., sponsored by multinational were selected from more than 480 large. -

Division of India; Indian and Pakistan Independent Dimensions

© 2020 IJRAR April 2020, Volume 7, Issue 2 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) Division of India; Indian and Pakistan Independent Dimensions – An overview *Nagaratna.B.Tamminal, Asst Professor of History, Govt First Grade Womens’s College, Koppal. Abstract Present paper takes a broad overview of independence on Indian subcontinent particularly India and Pakistan in their subsequent post independence dimensions. In August, 1947, when, after three hundred years in India, the British finally left, the subcontinent was partitioned into two independent nation states: Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan. Immediately, there began one of the greatest migrations in human history, as millions of Muslims trekked to West and East Pakistan (the latter now known as Bangladesh) while millions of Hindus and Sikhs headed in the opposite direction. Many hundreds of thousands never made it.Across the Indian subcontinent, communities that had coexisted for almost a millennium attacked each other in a terrifying outbreak of sectarian violence, with Hindus and Sikhs on one side and Muslims on the other—a mutual genocide as unexpected as it was unprecedented. In Punjab and Bengal—provinces abutting India’s borders with West and East Pakistan, respectively—the carnage was especially intense, with massacres, arson, forced conversions, mass abductions, and savage sexual violence. Some seventy-five thousand women were raped, and many of them were then disfigured or dismembered. Nisid Hajari, in “Midnight’s Furies” (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), his fast-paced new narrative history of Partition and its aftermath, writes, “Gangs of killers set whole villages aflame, hacking to death men and children and the aged while carrying off young women to be raped. -

Hardware-Enabled Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Security

Hardware-Enabled Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Security KUN YANG, HAOTING SHEN, DOMENIC FORTE, SWARUP BHUNIA, and MARK TEHRANIPOOR, University of Florida The pharmaceutical supply chain is the pathway through which prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs are delivered from manufacturing sites to patients. Technological innovations, price fluctuations of raw materials, as well as tax, regulatory, and market demands are driving change and making the phar- maceutical supply chain more complex. Traditional supply chain management methods struggle to protect the pharmaceutical supply chain, maintain its integrity, enhance customer confidence, and aid regulators in tracking medicines. To develop effective measures that secure the pharmaceutical supply chain, it is impor- tant that the community is aware of the state-of-the-art capabilities available to the supply chain owners 23 and participants. In this article, we will be presenting a survey of existing hardware-enabled pharmaceutical supply chain security schemes and their limitations. We also highlight the current challenges and point out future research directions. This survey should be of interest to government agencies, pharmaceutical compa- nies, hospitals and pharmacies, and all others involved in the provenance and authenticity of medicines and the integrity of the pharmaceutical supply chain. CCS Concepts: • Security and privacy → Hardware security implementation; Additional Key Words and Phrases: Pharmaceutical supply chain, security, privacy, traceability, authentica- tion ACM Reference format: Kun Yang, Haoting Shen, Domenic Forte, Swarup Bhunia, and Mark Tehranipoor. 2017. Hardware-Enabled Pharmaceutical Supply Chain Security. ACM Trans. Des. Autom. Electron. Syst. 23, 2, Article 23 (December 2017), 26 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3144532 1 INTRODUCTION The pharmaceutical supply chain, which spans many geographical regions and involves numer- ous parties, is the pathway through which prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) drugs are delivered from manufacturing sites to patients. -

Pill Presses: an Overlooked Threat to American Patients

ILLEGAL PILL PRESSES: AN OVERLOOKED THREAT TO AMERICAN PATIENTS A Joint Project by: national association of Boards of pharmacy, National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators, and THE PARTNERSHIP FOR SAFE MEDICINES March 2019 Executive Summary For less than $500, an individual with ill intent can purchase a pill press and a counterfeit pill mold that allows them to turn cheap, readily available, unregulated ingredients into a six-fi g- ure profi t. Criminals rely upon these pill presses to create dangerous counterfeit medications with toxic substances such as cheaply imported fentanyl (analogues). Their deadly home- made products have reached 46 states in the United States. Of grave concern is the signifi - cant lack of manufacturing control utilized in the making of these counterfeit products. The inexperience of these “garage manufacturers” has killed unsuspecting Americans in 30 states. Counterfeit medications that can kill someone with a single pill are a reality that is increas- ing at an alarming rate. This is a critical health issue that all three of our organizations are urgently striving to stay on top of. How do these criminals get their hands on pill presses? How are they evading customs in- spections? Is possession of these presses illegal and if so, why are more people not charged with it? Recently, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators and The Partnership for Safe Medicines joined together to research the extent of the pill press challenge for law enforcement and other fi rst responders. Key fi ndings include: © March 2019 NABP, NADDI, and PSM ● 2 Illegal Pill Presses: An Overlooked Threat 1. -

Indonesia's Transformation and the Stability of Southeast Asia

INDONESIA’S TRANSFORMATION and the Stability of Southeast Asia Angel Rabasa • Peter Chalk Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited ProjectR AIR FORCE The research reported here was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. Further information may be obtained from the Strategic Planning Division, Directorate of Plans, Hq USAF. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rabasa, Angel. Indonesia’s transformation and the stability of Southeast Asia / Angel Rabasa, Peter Chalk. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. “MR-1344.” ISBN 0-8330-3006-X 1. National security—Indonesia. 2. Indonesia—Strategic aspects. 3. Indonesia— Politics and government—1998– 4. Asia, Southeastern—Strategic aspects. 5. National security—Asia, Southeastern. I. Chalk, Peter. II. Title. UA853.I5 R33 2001 959.804—dc21 2001031904 Cover Photograph: Moslem Indonesians shout “Allahu Akbar” (God is Great) as they demonstrate in front of the National Commission of Human Rights in Jakarta, 10 January 2000. Courtesy of AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE (AFP) PHOTO/Dimas. RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND® is a registered trademark. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of its research sponsors. Cover design by Maritta Tapanainen © Copyright 2001 RAND All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, -

Unit-Of-Use Versus Traditional Bulk Packaging

Student Projects PHARMACY PRACTICE Unit-of-Use Versus Traditional Bulk Packaging Tiffany So¹ and Albert Wertheimer, Ph.D.¹: ¹Department of Pharmacy Practice, Temple University School of Pharmacy, Philadelphia, PA Keywords: Unit-of-Use, Bulk Packaging, Adherence, Economic Analysis Abstract Background: The choice between unit-of-use versus traditional bulk packaging in the US has long been a continuous debate for drug manufacturers and pharmacies in order to have the most efficient and safest practices. Understanding the benefits of using unit-of- use packaging over bulk packaging by US drug manufacturers in terms of workflow efficiency, economical costs and medication safety in the pharmacy is sometimes challenging. Methods: A time-saving study comparing the time saved using unit-of-use packaging versus bulk packaging, was examined. Prices between unit-of-use versus bulk packages were compared by using the Red Book: Pharmacy’s Fundamental Reference. Other articles were reviewed on the topics of counterfeiting, safe labeling, and implementation of unit-of-use packaging. Lastly, a cost-saving study was reviewed showing how medication adherence, due to improved packaging, could be cost-effective for patients. Results: When examining time, costs, medication adherence, and counterfeiting arguments, unit-of-use packaging proved to be beneficial for patients in all these terms. Introduction often geared towards hospitals. Therefore, the difference Whether to use unit-of-use versus traditional bulk packaging between these two types of packaging is that unit-of-use is a continuous debate for drug manufacturers and packaging contains multiple doses while unit dose packaging pharmacies in order to have the most efficient and safest contains one dose.5 Bulk packaging contains one type of practices. -

Fake Pills Look Nearly Identical to the Real Prescription Pills and the Buyers/Users Are Often Unaware of How Deadly They Might Be

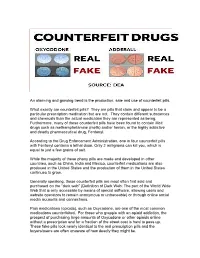

An alarming and growing trend is the production, sale and use of counterfeit pills. What exactly are counterfeit pills? They are pills that claim and appear to be a particular prescription medication but are not. They contain different substances and chemicals than the actual medication they are represented as being. Furthermore, many of these counterfeit pills have been found to contain illicit drugs such as methamphetamine (meth) and/or heroin, or the highly addictive and deadly pharmaceutical drug, Fentanyl. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration, one in four counterfeit pills with Fentanyl contains a lethal dose. Only 2 milligrams can kill you, which is equal to just a few grains of salt. While the majority of these phony pills are made and developed in other countries, such as China, India and Mexico, counterfeit medications are also produced in the United States and the production of them in the United States continues to grow. Generally speaking, these counterfeit pills are most often first sold and purchased on the “dark web” (Definition of Dark Web: The part of the World Wide Web that is only accessible by means of special software, allowing users and website operators to remain anonymous or untraceable) or through online social media accounts and connections. Pain medications (opioids), such as Oxycodone, are one of the most common medications counterfeited. For those who grapple with an opioid addiction, the prospect of purchasing large amounts of Oxycodone or other opioids online without a prescription and for a fraction of the street cost is hard to pass up. These fake pills look nearly identical to the real prescription pills and the buyers/users are often unaware of how deadly they might be. -

Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

The Global Return of the Wu Xia Pian (Chinese Sword-Fighting Movie): Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon by Kenneth Chan Abstract: In examining the way Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon grapples with cultural identity and Chineseness, this essay considers Lee’s construction of an image of “China” in the film, as well as its feminist possibilities. These readings reveal Lee’s conflicted critique of traditional Chinese cultural centrism and patri- archal hegemony. The wu xia pian, or Chinese sword-fighting movie, occupies a special place in the cultural memory of my childhood.1 Growing up in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Singapore, I remember with great fondness escaping from the British-based education system I attended and from the blazing heat of the tropical sun to the air-conditioned coolness of the neighborhood cinema. (This was long before cineplexes became fashionable.) Inevitably, a sword-fighting or kung fu flick from Hong Kong would be screening. The exoticism of one-armed swordsmen, fighting Shaolin monks, and women warriors careening weightlessly across the screen in- formed my sense and (mis)understanding of Chinese culture, values, and notions of “Chineseness” more radically than any Chinese-language lessons in school could have. The ideological impact of this genre should clearly not be underestimated, as cinematic fantasy is sutured into the cultural and political imaginary of China, particularly for the Chinese in diaspora.2 Like many moviegoers of Chinese ethnicity, I responded to Ang Lee’s cin- ematic epic Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) with genuine enthusiasm and anticipation.