Direct PDF Link for Archiving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

121 Residential Properties in Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire 1 Executive Summary Milton Keynes

121 RESIDENTIAL PROPERTIES IN BEDFORDSHIRE AND BUCKINGHAMSHIRE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MILTON KEYNES The portfolio comprises four modern freehold residential assets. Milton Keynes is a ‘new town’ built in the 1960s. The area Geographically, the properties are each connected to the major incorporates the existing towns of Bletchley, Wolverton and economic centres of Luton or Milton Keynes as well as being Stony Stratford. The population in the 2011 Census totalled commutable to Central London. 248,800. The government have pledged to double the population by 2026. Milton Keynes is one of the more successful (per capita) The current owners have invested heavily in the assets economies in the South East. It has a gross value added per during their ownership including a high specification rolling capita index 47% higher than the national average. The retail refurbishment of units, which is ongoing. sector is the largest contributor to employment. The portfolio offers an incoming investor the opportunity KEY FACTS: to acquire a quality portfolio of scale benefitting from • Britain’s fastest growing city by population. The population management efficiencies, low running costs, a low entry price has grown 18% between 2004 and 2013, the job base having point into the residential market, an attractive initial yield and expanded by 24,400 (16%) over the same period. excellent reversionary yield potential. • Milton Keynes is home to some of the largest concentrations PORTFOLIO SUMMARY AND PERFORMANCE of North American, German, Japanese and Taiwanese firms in the UK. No. of Assets 4 No. of Units 121 • Approximately 18% of the population can be found in the PRS, Floor area (sq m / sq ft) 5,068 / 54,556 with growth of 133% since 2001. -

LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills Landscape Character Type

Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills Landscape Character Type: LCT 10 Chalk Foothills B0404200/LAND/01 Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills (LCT 10) Key Characteristics Location An extensive area of land which surrounds the Ivinghoe Beacon including the chalk pit at Pitstone Hill to the west and the Hemel Hempstead • Chalk foothills Gap to the east. The eastern and western boundaries are determined by the • Steep sided dry valleys County boundary with Hertfordshire. • Chalk outliers • Large open arable fields Landscape character The LCA comprises chalk foothills including dry • Network of local roads valleys and lower slopes below the chalk scarp. Also included is part of the • Scattering of small former chalk pits at Pitstone and at Ivinghoe Aston. The landscape is one of parcels of scrub gently rounded chalk hills with scrub woodland on steeper slopes, and woodland predominantly pastoral use elsewhere with some arable on flatter slopes to • Long distance views the east. At Dagnall the A4146 follows the gap cut into the Chilterns scarp. over the vale The LCA is generally sparsely settled other than at the Dagnall Gap. The area is crossed by the Ridgeway long distance footpath (to the west). The • Smaller parcels of steep sided valley at Coombe Hole has been eroded by spring. grazing land adjacent to settlements Geology The foothills are made up of three layers of chalk. The west Melbury marly chalk overlain by a narrow layer of Melbourn Rock which in turn is overlain by Middle Chalk. -

Beyond the Compact City: a London Case Study – Spatial Impacts, Social Polarisation, Sustainable 1 Development and Social Justice

University of Westminster Duncan Bowie January 2017 Reflections, Issue 19 BEYOND THE COMPACT CITY: A LONDON CASE STUDY – SPATIAL IMPACTS, SOCIAL POLARISATION, SUSTAINABLE 1 DEVELOPMENT AND SOCIAL JUSTICE Duncan Bowie Senior Lecturer, Department of Planning and Transport, University of Westminster [email protected] Abstract: Many urbanists argue that the compact city approach to development of megacities is preferable to urban growth based on spatial expansion at low densities, which is generally given the negative description of ‘urban sprawl’. The argument is often pursued on economic grounds, supported by theories of agglomeration economics, and on environmental grounds, based on assumptions as to efficient land use, countryside preservation and reductions in transport costs, congestion and emissions. Using London as a case study, this paper critiques the continuing focus on higher density and hyper-density residential development in the city, and argues that development options beyond its core should be given more consideration. It critiques the compact city assumptions incorporated in strategic planning in London from the first London Plan of 2004, and examines how the both the plan and its implementation have failed to deliver the housing needed by Londoners and has led to the displacement of lower income households and an increase in spatial social polarisation. It reviews the alternative development options and argues that the social implications of alternative forms of growth and the role of planning in delivering spatial social justice need to be given much fuller consideration, in both planning policy and the delivery of development, if growth is to be sustainable in social terms and further spatial polarisation is to be avoided. -

Territorial Stigmatisation and Poor Housing at a London `Sink Estate'

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2020, Volume 8, Issue 1, Pages 20–33 DOI: 10.17645/si.v8i1.2395 Article Territorial Stigmatisation and Poor Housing at a London ‘Sink Estate’ Paul Watt Department of Geography, Birkbeck, University of London, London, WC1E 7HX, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 4 August 2019 | Accepted: 9 December 2019 | Published: 27 February 2020 Abstract This article offers a critical assessment of Loic Wacquant’s influential advanced marginality framework with reference to research undertaken on a London public/social housing estate. Following Wacquant, it has become the orthodoxy that one of the major vectors of advanced marginality is territorial stigmatisation and that this particularly affects social housing es- tates, for example via mass media deployment of the ‘sink estate’ label in the UK. This article is based upon a multi-method case study of the Aylesbury estate in south London—an archetypal stigmatised ‘sink estate.’ The article brings together three aspects of residents’ experiences of the Aylesbury estate: territorial stigmatisation and dissolution of place, both of which Wacquant focuses on, and housing conditions which he neglects. The article acknowledges the deprivation and various social problems the Aylesbury residents have faced. It argues, however, that rather than internalising the extensive and intensive media-fuelled territorial stigmatisation of their ‘notorious’ estate, as Wacquant’s analysis implies, residents have largely disregarded, rejected, or actively resisted the notion that they are living in an ‘estate from hell,’ while their sense of place belonging has not dissolved. By contrast, poor housing—in the form of heating breakdowns, leaks, infes- tation, inadequate repairs and maintenance—caused major distress and frustration and was a more important facet of their everyday lives than territorial stigmatisation. -

Aylesbury NDC Community Health Profile

Aylesbury NDC Community Health Profile July 2004 Prepared by Christian Castle and Philip Atkinson On behalf of the Public Health Department, Southwark Primary Care Trust Southwark Primary Care Trust: Aylesbury NDC Community Health Profile Executive Summary: Key Facts This report presents the findings of the Community Health Profile for the Aylesbury New Deal for Communities (NDC) Partnership. The partnership is aiming to regenerate the Aylesbury Estate situated in Southwark, south London, with some of the £56.2 million of NDC funds awarded to the partnership in 1999. Key findings for the following subjects were: Demography • There were approximately 8,345 people living on the Aylesbury Estate in 2001. • The population of Faraday Ward (which contains the Aylesbury Estate) has risen by 17% between 1991 (10,559) and 2001 (12,697). • Faraday Ward contains the fifth largest population in Southwark, yet occupies the fourth smallest area (87 hectares). • The Aylesbury Estate contains a younger population than the UK - 75% of Aylesbury Estate is under the age of 45 compared to 60% of the UK population. • Faraday Ward contains a larger proportion of ethnic minorities than both Southwark and the UK. In particular there are a large proportion of people of black (35%, especially African), and Chinese/other origins (5%). • The age distribution of all ethnic groups, including people of black and Chinese origin are similar to both Southwark and the UK. • Faraday Ward contains large numbers of both black and Chinese people, who tend to be young compared to the general population. This leads to a younger population overall compared to Southwark and the UK. -

Aylesbury Vale North Locality Profile

Aylesbury Vale North Locality Profile Prevention Matters Priorities The Community Links Officer (CLO) has identified a number of key Prevention Matters priorities for the locality that will form the focus of the work over the next few months. These priorities also help to determine the sort of services and projects where Prevention Matters grants can be targeted. The priorities have been identified using the data provided by the Community Practice Workers (CPW) in terms of successful referrals and unmet demand (gaps where there are no appropriate services available), consultation with district council officers, town and parish councils, other statutory and voluntary sector organisations and also through the in depth knowledge of the cohort and the locality that the CLO has gained. The CLO has also worked with the other CLOs across the county to identify some key countywide priorities which affect all localities. Countywide Priorities Befriending Community Transport Aylesbury Vale North Priorities Affordable Day Activities Gentle Exercise Low Cost Gardening Services Dementia Services Social Gardening Men in Sheds Outreach for Carers Background data Physical Area The Aylesbury Vale North locality (AV North) is just less than 200 square miles in terms of land area (500 square kilometres). It is a very rural locality in the north of Buckinghamshire. There are officially 63 civil parishes covering the area (approximately a third of the parishes in Bucks). There are 2 small market towns, Buckingham and Winslow, and approximately 70 villages or hamlets (as some of the parishes cover more than one village). Population The total population of the Aylesbury Vale North locality (AV North) is 49,974 based on the populations of the 63 civil parishes from the 2011 Census statistics. -

Core Strategy: Preferred Options Summary Document April 2009

Luton and South Bedfordshire Joint Committee Local Development Framework Core Strategy: Preferred Options Summary Document April 2009 …shape your future… Luton and South Bedfordshire Joint Committee Core Strategy Preferred Options Summary Document 1. INTRODUCTION In 2007, the Luton and South Bedfordshire Joint Committee sought views on the delivery of Document development, to help inform future planning. Options sought to respond to some of the challenges this area faces. The Joint Committee want your views on its preferred options. Summary 2. BACKGROUND Options The Government's growth agenda requires that significant new development is delivered in Luton and southern Bedfordshire. In total, we need to The Committee is planning for 43,000 new homes between referred 2001 and 2031, and 35,000 new jobs, together with significant new supporting infrastructure. P The Core Strategy is the first planning document to address this agenda. Earlier public consultation and over twenty technical studies have informed this document. Strategy This leaflet is seeking views on the document to help the Committee plan growth sustainably. The Core full document: The Luton and South Bedfordshire Joint Committee Core Strategy: Preferred Options April 2009, and associated questionnaire are available to viewonline at www.shapeyourfuture.org.uk. We encourage you to read this and complete the questionnaire. Committee 3. THE SPATIAL STRATEGY: A SUMMARY Joint A key matter for the document is where should development go. The resulting Spatial Development Principles and associated policy, taken from the full document, is set out below for your consideration. Bedfordshire A) A Framework of Strategic Transport Infrastructure South To deliver sustainable development, it is important to ensure as much as possible is accessible by and public transport and other alternatives to the private car as well as responsibly planning for car use. -

The Berkshire Echo 39

The Berkshire Echo Issue 39 l Missing historical document l New to the Archives l Cold death for baby boy l Local woman gets ducked! l Workhouse master misuses rations From the Editor Dates for Your Diary An historical introduction Welcome to the spring edition of I would like to take this opportunity Find out more about your family or The Berkshire Echo, although with this to publicly thank the BRO staff for local history with a visit to the BRO. year’s non-existent winter it feels as all their hard work and dedication to Why not put your name down for though spring has been in the air for making you happy. one of the free BRO introductory sometime! In this issue: read about the visits. Remaining dates for 2007 recent purchase of a long lost historical However there are no noticeable are: 9th July and 8th October. document; fi nd out what really went on changes to satisfaction since the Just call us on 0118 901 5132 or ask at the workhouse; read the sad story of previous survey in 2004. So although at Reception for details. a baby’s death; celebrate the abolition we are not doing any worse, equally we of the Slave Trade; fi nd out who gets have not done any better. The survey See you in Faringdon! ducked in water; and catch up on recent produces a ‘wish list’ from visitors, Come along and investigate your additions to the BRO archive. and we will be looking again at how family, house and/or local history we ensure our public research rooms at the Faringdon History Day. -

Royal Connections to Aylesbury

Royal AYLESBURY Connections William I demanded green geese and eels whenever he visited! At the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror took the manor of Aylesbury for himself, and it is listed as a royal manor in the Domesday Book of 1086. Some lands here were granted by the king to citizens upon the extraordinary tenure that the owners should provide straw for the monarch's bed, William the Conqueror sweet herbs for his chamber, and two green geese and three eels for his table, whenever he should visit Aylesbury The Kings Head, in Market Square, Aylesbury is an historic ancient coaching inn dating back to about 1450, though the cellars may be 13th century. It is one of the St Mary's Church, the oldest building in Aylesbury dates to the 13th century : Roger Marks oldest public houses with a coaching yard in the south of England. It is now owned by the National Trust and is open to the public. King Henry VI possibly stayed here in the 15th century while on a tour of the country with his new wife Margaret of Anjou. A stained glass panel was later inserted in the front window of the inn, depicting the king and queen's coats of arms. Henry VIII declared Aylesbury the new county town of Buckinghamshire in 1529. It is thought he did so to curry favour with Thomas Boleyn (father of Anne Boleyn) who owned Aylesbury Manor. According to local folklore, Henry subsequently wooed Anne in the Solar Room above the Great Hall in the Kings Head in 1533. -

Existing Leisure Facilities in and Around Dacorum Borough Council

Existing Leisure Facilities in and around Dacorum Borough Council Table 6.1 Leisure Centres in and around Dacorum Area Name Address Postcode Hertfordshire Moat House, London Road, Markyate Club Motivation Markyate AL3 8HH Hemel Jarman Centre, Old Crabtree Lane, Hemel Hempstead Leisureworld Hempstead, Hertfordshire HP2 4JW Hemel Hempstead Sports Centre Park Road, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire HP1 1JS Esporta Orchard Fields, Hemel Hempstead HP2 7DF Longdean Sports CentRumballs Road, Bennetts End HP3 8JB Shendish Manor Health Club London Road, Apsley HP3 0AA Marlowes Fitness Centre The Marlowes Centre, Hemel Hempstead HP1 1DX Spirit Health and Holiday Inn, Breakspear Way, Hemel Fitnesss Hempstead HP2 4UA Berkhamsted Sports Lagley Meadow, Douglas Gardens, Berkhamsted Centre Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, HP4 3QQ 172-176, High Street, Berkhamsted, Fitness First Hertfordshire HP4 3AP Tring Tring Sports Centre Mortimer Hill, Tring, Hertfordshire HP23 5JU Champneys Health Resort Champneys, Wigginton, Tring, Hertfordshire HP23 6HY Harveys 58-59 High Street, Tring HP23 5AG Exclusively Ladies 68 - 70 Mortimer Hill, Tring HP23 5EE Other The Chiltern Pools Chiltern Avenue, Amersham, Buckinghamshire HP6 5AH The Riviera Suite Ski Centre Lakeside, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, HP19 0FX Hartwell House, Oxford Road, Stone, Aylesbury, The Hartwell Spa Buckinghamshire HP17 8NL Body Flex Gym 113, Cambridge St, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire HP20 1BT Reflexions Health and Leisure Watermead, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire HP19 0FY Curves 61-63 High Street, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire -

Dacorum Feeling Unwell? Which NHS Service So Why Not Add Is Right for You? It to Your Basket When You Do Your Weekly Shop?

Add it to your shopping basket Healthy NHS Hertfordshire spends around £9 million each year on medicines for things like headaches, hayfever, indigestion, colds, help on the coughs, flu, constipation and diarrhoea. These medicines can be High Street bought easily and usually cheaply “over the counter” from your local pharmacy, supermarket or store. The money that the NHS spends on these medicines is money that cannot be used to help patients with more complex health problems. Dacorum Feeling unwell? Which NHS service So why not add is right for you? it to your basket when you do your weekly shop? Pharmacists are experts in medicines and minor illnesses. They can give you advice on lots of common health problems, for example emergency contraception and many can help you to give up smoking and can advise you on how to lead a healthier life. Most now have a private consultation room where you can speak to your pharmacist without other people hearing. In Hertfordshire we have more than 200 pharmacies and several open early (around 7am) and close late (around 11pm). You can find out where these are by visiting www.nhs.uk/find and selecting the If you would like a copy of this document in large print, Braille, on “find a service” option or you can phone NHS Direct on0845 46 47 CD or as an audio file, or if you would like this information explained who will help you find the one nearest to where you are. in another language please telephone 01707 369705. You don’t need to make an appointment to speak to the pharmacist. -

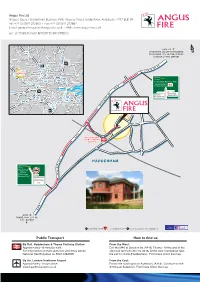

HADDENHAM Public Transport How to Find Us All

Angus Fire Limited Haddenham Business Park Angus Fire Ltd Pegasus Way, Haddenham Angus House, Haddenham Business Park, Pegasus Way, Haddenham, Aylesbury, HP17 8LB, UK Aylesbury HP17 8LB Tel: +44 (0)1844 293600 • Fax: +44 (0)1844 293664 Email: [email protected] • Web: www.angusfire.co.uk Tel: +44 (0) 1844 265000 Fax: +44 (0) 1844 265163 AllALL v VISITORSisitors pl PLEASEease rREPORTeport t TOo reception RECEPTION www.angusfire.co.uk A418 TO A508 10 AYLESBURY, LEIGHTON BUZZARD, M1 A1 N 14 A43 A5 A421 9 DUNSTABLE, M1, MILTON KEYNES, Milton A505 A422 13 10 A131 LONDON LUTON AIRPORT Keynes A6 M11 M40 9 A10 A43 STANSTED A421 A5 10 AIRPORT A4146 Stevenage Stevenage A120 A120 Braintree Luton 7 8a Bicester 8 9 Dunstable A5 D A602 Bishop’s R A41 A418 9 A131 A41 LUTON A1(M) Stortford R Y Aylesbury AIRPORT A130 B U A41 E S A418 A130 A12 AY L A41Hemel M1 4 8a HaddenHaddenhhaam A10 7 Oxford 3 Hatfield A414 Chelmsford 8 Hempstead A12 A4010 2121a 7 23 A413 20 6 25 27 Oxford High 19 Borehamwood M25 A12 A130 A418 A34 M40 5 A10 Thame Wycombe Watford M11 28 A355 M25 M1 A127 Haddenham Business Park A406 A12 4 29 3 2 C Basildon H Haddenham & 16 A40 U 1 A13 8 Thame Parkway Maidenhead A13 1 R Slough UxbridgUxbridgee LONDON 30 4 C 15 A H 8/9 M4 Dartford 1a W Reading A316 A2 1b Gravesend A A205 Y M4 10 13 HEATHROW A24 2 Chearsley Bracknell A2 1 D 11 AIRPORT A3 A23 A20 A2 Newbury 12 3 R Kingsey Cuddington A322 A232 A21 Y Haddenham 3 4 M20 A33 M25 Croydon M2 R U 4 3 4 10 A22 5 M26 B A339 Woking 9 A217 M20 M3 A3 S A331 E Basingstoke 7 M25 Sevenoaks 8 6 Maidstone L Guildford 8 A21 A26 Y 6 Dorking A22 A Farnham M23 A24 9 A26 A31 A3 GATWICK AIRPORT 10 A22 S T A N B R Y D E I R A D D E I G M W E P S E A H H G N 8 A T R 1 S Y C D U A W 4 S W R O A HADDENHAM & T U H THAME PARKWAY C STATION D R N TO S A O N S TAT I R D D R D E R M A HADDENHAM H Y T R Aylesbury A418 U Stone B Haddenham S E route for goods vehicles L Y 1 A Haddenham 1 4 miles Business Park Haddenham Haddenham & Thame Parkway 8 1 4 A A418 TO THAME, M40 JCT 8A, A40, OXFORD Give Way 2013 TM Tel: 0800 019 0027.