Constructions of the Fat Child in British Juvenile Fiction (1960-2010)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE WESTF1ELD LEADER the UADING AMP HOST WIDELY Chtlulated WEEKLY NEWSPAPE* in UNION COUNTY

THE WESTF1ELD LEADER THE UADING AMP HOST WIDELY CHtlULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPE* IN UNION COUNTY .. la* Second Class Matter -NINTH VEAI-No. 51 Post Office. Weetfleld. N. 1. Published WE8TFIEU), NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBEB 1, 1949 Every Thursday. Boro School Bus 11 New Teachers Join Faculty Warns Against Jiina to be Topic Schedule Ready Of Iest6eld Public Schools Polio Scare Doerr To Head The Westfield public schools will open with a full staff on To Start Thursday Wednesday under the direction of Dr. S. N. Ewan Jr., supervising In Westfield _4t Adult School principal. There have been 11 new teachers, one new nurse and one new secretary employed for this school year. Seven of these are in United Campaign Two BUM* to the elementary field, one in the junior high school and three in the Carney Reports 3 China Institute Director Leader of Transport Pupils senior high school, Two former More Infantile Budget Committee For October Drive Special Count, All Chineae Faculty On Four Routes teachers will return from leave of 2500 Dividend absence. Miss Melissa Fouratte Cases This Week Appointed by Samuel Kinney Dr. Chih Menu, director of China Institute in America, baa or- Two buses, each to maintain two returns to Roosevejt Junior High nniwd «special courie tot tbe Westfield Adult School under the title School after a year in Scotland as Two more Westfield familes were Charles A. Doerr, 26 Fair Hill road has been elected general routes, will be provided by the affected by poliomyelitis this week, chairman of Weetfleld's 1949 United Campaign. Announcement of oj "CMna "> Tr»n»ition." It will be presented by eight Chinese lec- Somerset Bus Co. -

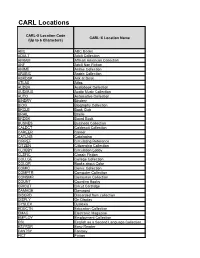

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Springfield College and DAY SEARCH ENGINES? Rte

Mailed free to requesting homes in Webster, Dudley and the Oxfords 508-764-4325 COMPLIMENTARY HOME DELIVERY/75¢ ON NEWSSTANDS ONLINE: WWW.WEBSTERTIMES.NET “Wherever you go, no matter what the weather, always bring your own sunshine.” Friday, December 19, 2008 DiDonato praised for historical preservation BY PATRICK SKAHILL ments laid untouched in “This stuff from a historical TIMES STAFF WRITER DiDonato’s house, but point of view is pure gold,” DUDLEY — More than during a cleaning some- Historical Commission member 60 years ago, Tony time in the 1970s the Michael Branniff told selectmen DiDonato happened longtime selectmen Monday, Dec. 15. “We have to say upon a innocuous bag of decided to haul the doc- bravo Tony, well done — we’re glad documents as he worked uments out of storage. you didn’t let that bag go.” at a construction site on He marched the mate- Last month, restoration of the West Main Street. rials down to Town Hall late 18th and 19th century docu- “Up on the beam I saw and officials were over- ments was completed at the this brown bag and I joyed at what they saw Northeast Document Conservation pulled it down and there —DiDonato was holding Center — a move town officials was all this stuff in there a bag of full of praised as a step in the right direc- [that] looked important,” untouched documents, tion for ensuring this priceless por- DiDonato recalled. DiDonato some of which dated For years, the docu- back to the 1780s. Turn To DUDLEY, page 17 Slota resigns from search committee Teresa A. -

VERBAL BEHAVIOR by B. F. Skinner William James Lectures Harvard

VERBAL BEHAVIOR by B. F. Skinner William James Lectures Harvard University 1948 To be published by Harvard University Press. Reproduced by permission of B. F. Skinner† Preface In 1930, the Harvard departments of psychology and philosophy began sponsoring an endowed lecture series in honor of William James and continued to do so at irregular intervals for nearly 60 years. By the time Skinner was invited to give the lectures in 1947, the prestige of the engagement had been established by such illustrious speakers as John Dewey, Wolfgang Köhler, Edward Thorndike, and Bertrand Russell, and there can be no doubt that Skinner was aware that his reputation would rest upon his performance. His lectures were evidently effective, for he was soon invited to join the faculty at Harvard, where he was to remain for the rest of his career. The text of those lectures, possibly somewhat edited and modified by Skinner after their delivery, was preserved as an unpublished manuscript, dated 1948, and is reproduced here. Skinner worked on his analysis of verbal behavior for 23 years, from 1934, when Alfred North Whitehead announced his doubt that behaviorism could account for verbal behavior, to 1957, when the book Verbal Behavior was finally published, but there are two extant documents that reveal intermediate stages of his analysis. In the first decade of this period, Skinner taught several courses on language, literature, and behavior at Clark University, the University of Minnesota, and elsewhere. According to his autobiography, he used notes from these classes as the foundation for a class he taught on verbal behavior in the summer of 1947 at Columbia University. -

Drug Education and Its Publics in 1980S Britain

International Journal of Drug Policy 88 (2021) 103029 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Drug Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugpo Policy Analysis Just say know: Drug education and its publics in 1980s Britain Alex Mold Centre for History in Public Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 15-17 Tavistock Place, London, WC1H 9SH, United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Until the 1980s, anti-drug education campaigns in the UK were rare. This article examines the reasons behind a Heroin policy shift that led to the introduction of mass media drug education in the mid 1980s. It focuses on two Drug education campaigns. ‘Heroin Screws You Up’ ran in England, and ‘Choose Life Not Drugs’ ran in Scotland. The campaigns Health education were different in tone, with ‘Heroin Screws You Up’ making use of fear and ‘shock horror’ tactics, whereas History of drug use ‘Choose Life Not Drugs’ attempted to deliver a more positive health message. ‘Heroin Screws You Up’ was criticised by many experts for its stigmatising approach. ‘Choose Life Not Drugs’ was more favourably received, but both campaigns ran into difficulties with the wider public. The messages of these campaigns were appro priated and deliberately subverted by some audiences. This historical policy analysis points towards a complex and nuanced relationship between drug education campaigns and their audiences, which raises wider questions about health education and its ‘publics’. In April 1986, the cast of teen TV soap, Grange Hill, released a song wanted to be seen to take action on drugs, leading to the introduction of titled ‘Just say no’. -

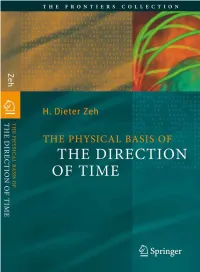

The Physical Basis of the Direction of Time (The Frontiers Collection), 5Th

the frontiers collection the frontiers collection Series Editors: A.C. Elitzur M.P. Silverman J. Tuszynski R. Vaas H.D. Zeh The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active scientists in all areas to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, consciousness and complex systems – the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. InformationandItsRoleinNature The Thermodynamic By J. G. Roederer Machinery of Life By M. Kurzynski Relativity and the Nature of Spacetime By V. Petkov The Emerging Physics of Consciousness Quo Vadis Quantum Mechanics? Edited by J. A. Tuszynski Edited by A. C. Elitzur, S. Dolev, N. Kolenda Weak Links Life – As a Matter of Fat Stabilizers of Complex Systems The Emerging Science of Lipidomics from Proteins to Social Networks By O. G. Mouritsen By P. Csermely Quantum–Classical Analogies Mind, Matter and the Implicate Order By D. Dragoman and M. Dragoman By P.T.I. Pylkkänen Knowledge and the World Quantum Mechanics at the Crossroads Challenges Beyond the Science Wars New Perspectives from History, Edited by M. -

2017 Producers Book Finalists

PRODUCERS BOOK & PRINT SOURCE LIST Pre-Festival Edition THE 2017 PRODUCERS BOOK A LETTER FROM THE SCREENPLAY & FILM COMPETITION DIRECTORS Hello! Each year, we prepare our annual Producers Book which contains loglines and contact information for the year’s top scripts in our various Script Competitions. Please feel free to reach out to any of the writers listed here to request a copy of their scripts. Also included is our Print Source List containing information for all films selected for the 2017 Festival. This year’s Semifinalists and Finalists were chosen from a field of 9,487 scripts entered in our Screenplay, Digital Series, Playwriting, and Fiction Podcast Competitions. Each year we are amazed by the professional quality and talent that we receive and this year wasn’t any different. The Competition is open to feature-length scripts in the genres of drama, comedy, sci-fi, and horror; teleplay pilots and specs, short scripts, stage plays, fiction podcast scripts, and digital series scripts. Year after year, our strive in programming the Austin Film Festival film slate is to discover and champion the writers and those who can translate amazing stories to the screen. We received over 5,000 film submissions this year and had the task of whittling it down to 182 films that embody our mission and passion for storytelling. It was a harrowing task, but it led to our strongest year of film yet. We’re so proud of this year’s diverse group of filmmakers and unique voices and can’t wait for these works to be seen, shared, and loved. -

0.GEMATRIA DATABASE.Pages

GEMATRIA - DATABASE ! Bavarian Illuminati Est. May 1st, 1776} 5/01/1776 ! Scottish Rite Est. May 31, 1801 } 5/31/1801 Knights Templar ARRESTED on Oct. 13, 1307 } 10/12/1307 ! Knights Templar FOUNDED in Jerusalem, Israel: 1119 ! Skull & Bones 322 FOUNDED in 1832 at Yale University) (Russell Trust Association - Parent Organization) 322 references 322 BC ! Vatican City Est. February 11, 1929 (109 acres) ! One legend is that the numbers in the society's emblem ("322") represent "founded in '32, 2nd corps", referring to a first Corps in an unknown German university.[22][23] ! Convocation founded in 1539 (3rd Papal Bull) Jesuits founded in 1541 Copernicus of 1543 (Ball Earth) The Council of Trent founded in 1545 ! (Christopher Columbus) America discovered in 1492 (2 Papal Bulls) 1912 = Titanic sank 1913 = Federal Reserve Established 1914 = First World War 1917 = Bolshevik Communist Invasion ! Jewish Bolshevism, also known as Judeo-Bolshevism, is an antisemitic and anti-communist canard [citation needed] which alleges that the Jews were at the origin of the Russian Revolution and held the primary power among Bolsheviks. Similarly, the Jewish Communism theory implies that Jews have been dominating the Communist movements in the world. It is similar to the ZOG conspiracy theory, which asserts that Jews control world politics. The expressions have been used as a catchword for the assertion that Communism is a Jewish conspiracy. ! Hexagram = Star of David ! Pythagoras the Samian or Pythagoras of Samos (570-495 BC) was a mathematician, Ionian Greek -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Buses from Grange Hill

Buses from Grange Hill 462 FR Limes Farm Estate O Copperfield GH D A LL L Hail & Ride MANOR ROA section AN E Manor Road C St. Winifred’s Church D Grange Hill M AN W A AR MANOR ROAD FO REN Grange Hill C RD T. LONG B WAY G R Manford Way G E Manford Primary School CRE RANGE E N SCEN Brocket Way T Manford Way Hainault Health Centre Destination finder Destination Bus routes Bus stops Destination Bus routes Bus stops B L Barkingside High Street 462 ,a ,c Limes Farm Estate Copperfield 462 ,b ,d Hainault Waverley Gardens Longwood Gardens 462 ,a ,c The Lowe Beehive Lane 462 ,a ,c M Brocket Way 362 ,c Manford Way 462 ,a ,c C Hainault Health Centre Chadwell Heath o High Road 362 ,c Manford Way 462 ,a ,c Manford Primary School Chadwell Heath Lane 362 ,c Manor Road St. Winifred's Church 462 ,b ,d Elmbridge Road New North Road Cranbrook Road for Valentines Park 462 ,a ,c Harbourer Road Marks Gate Billet Road 362 ,c E Eastern Avenue 462 ,a ,c N New North Road Harbourer Road 362 ,c Elmbridge Road 462 ,a ,c New North Road Yellow Pine Way 362 ,c F Buses from Grange Hill Fairlop 462 ,a ,c BusesR from Grange Hill Romford Road 362 ,c Forest Road New North Road Fremantle Road 462 ,a ,c Hainault Forest Golf Club for Fairlop Waters Yellow Pine Way Barkingside High Street Boulder Park Rose Lane Estate 362 ,c Forest Road 462 ,a ,c 462 for Fairlop Waters Boulder Park FR Limes Farm Estate W Copperfield O D Fullwell Cross for Leisure Centre 462 ,a ,c WhaleboneGH Lane North 362 ,c A Romford RoadLL L Hail & Ride G MANOR ROA section WhaleboneAN Lane North 362 ,c Gants Hill 462 ,a ,c Fairlop Romford Road Whalebone GroveE Manor Road Hainault Forest Golf Club H Woodford Avenue C 462 ,a ,c St. -

NOFX: Popular Punks Sellout

MAnCH 7,2001 • THE ORION C!& ((Well you're all a bunch o/posers because this is OU1'fitst time playing in Chico. JJ - FAT MIKE, NOFX ;., NOFX: Popular punks sellout sho ~The BrickWorks hosts hugely It was that kind of sarcasm that remained "Straight Edgc" and their reggac tunc "Eat the drummer Cecil Lossy. constant throughout the night us the band interacted Meek," He also blew his trumpet on a few songs. The band preceding NOFX showed that getting popular NOFX, which sold out with the crowd after each and every song. Guitarist Eric Melvin sported his usual nappy plastcred seemed to be the theme of the night. "I think I'm having a good ·time here in Chico," dreadlocks and cven traded his guitar for an ·~Hi. We're thc Mad Caddies, and we're drunk," the show a month in advance said Fat Mike. "I'm having a lot more fun tonight accordion on their closing song. Melvin continued s:tid singer Chuck (the b:tnd members don't go by because I'm drunk." to stand on the stngc and squeeze the accordion their last namcs). MATT BROWN NOFX's show had something to offer for all after thc rest of the band hnd exited. Thc Mad Caddies can be described as :tn S~',O'l' WI<ll'lll< typcs of fnns, as they plnyed songs Eric Ghent's galloping dnnnbeals bat insane circus gone punk. A seven-piece frolll th·at ranged from their oldest ulbum to tered The Brick Works' sOllnd system. Sanla Barbara, the ska band forccd The Briek . -

4/2011 • TEOLOGIAN YLIOPPILAIDEN TIEDEKUNTAYHDISTYKSEN JULKAISU VUODESTA 1853 KYYHKYNEN Kyyhkynen 4/2011

4/2011 • TEOLOGIAN YLIOPPILAIDEN TIEDEKUNTAYHDISTYKSEN JULKAISU VUODESTA 1853 KYYHKYNEN Kyyhkynen 4/2011 3 PÄÄKIRJOITUS 15 RASVAKUDOKSESTA, SEN PUUTTUMISESTA JA 4 PUHEENJOHTAJISTON AVAUTUMINEN EMPAATISESTA KIRJOITUSKÄYTÖKSESTÄ 5 HYY:STÄ PÄIVÄÄ 17 VIERASMAA: HENGELLISET LÄSKIT 6 SUURI HUIPUTUSYKSIKKÖ? 18 GRASSO QUATTRO STAGIONI 7 MÄSSÄILIJÄN OPAS JERUSALEMIIN 19 OIKOTIE ONNEEN 9 SUPERFOOD = SUPERNOOB?! 20 MIETTEITÄ VIRVOITUSJUOMATEOLLISUUDESTA 10 LÄSKI ON SYNTIÄ 21 RETROPELIKORNERI X2 12 ATLETICO LÄSKI 23 SARJAKUVAT 14 MUSAPLEKSIT Tilaa nyt Kotimaa-lehti opiskelijahintaan -50%! HALUATKO perehtyä kirkon ja seurakuntien tilanteeseen? Hyödynnä TAHDOTKO pysyä ajan tasalla kirkkopolitiikan kiemu- etusi! roista, päivän polttavista puheenaiheista ja vallitsevasta mielipideilmastosta? KAIPAATKO tietoa alasi avoimista työpaikoista? Kotimaa on jokaisen teologian opiskelijan tuore 12 kk ja monipuolinen tietolähde. Se kertoo kirkon ja seurakuntien asiat laajemmin kuin mikään muu € lehti. Se herättää keskustelua arvoista, jotka tämän 59 € päivän Suomessa vallitsevat. (norm. 118 ) TILAUKSET Soita p. 020 754 2333 Lähetä sähköpostia Kotimaa-yhtiöt asiakaspalvelu ma–pe klo 8–16 tilauspalvelut@kotimaa.fi Lankaverkosta: 8,21 senttiä/puhelu + 6,9 senttiä/minuutti, Mainitse viestissä tarjoustunnus KY11 Matkapuhelimesta: 8,21 senttiä/puhelu + 14,9 senttiä/minuutti 2 PÄÄKIRJOITUS: RAKKAILLE LÄSKIPÄILLE Vuoden kierto lähenee epäluonnollisuudessaan loppuaan ja samaa rohkenen sanoa myös kansakuntamme terveysintoilujen aaltoiluista. Ikiaikainen pyrkimyksemme yllä-