Drug Education and Its Publics in 1980S Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE WESTF1ELD LEADER the UADING AMP HOST WIDELY Chtlulated WEEKLY NEWSPAPE* in UNION COUNTY

THE WESTF1ELD LEADER THE UADING AMP HOST WIDELY CHtlULATED WEEKLY NEWSPAPE* IN UNION COUNTY .. la* Second Class Matter -NINTH VEAI-No. 51 Post Office. Weetfleld. N. 1. Published WE8TFIEU), NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBEB 1, 1949 Every Thursday. Boro School Bus 11 New Teachers Join Faculty Warns Against Jiina to be Topic Schedule Ready Of Iest6eld Public Schools Polio Scare Doerr To Head The Westfield public schools will open with a full staff on To Start Thursday Wednesday under the direction of Dr. S. N. Ewan Jr., supervising In Westfield _4t Adult School principal. There have been 11 new teachers, one new nurse and one new secretary employed for this school year. Seven of these are in United Campaign Two BUM* to the elementary field, one in the junior high school and three in the Carney Reports 3 China Institute Director Leader of Transport Pupils senior high school, Two former More Infantile Budget Committee For October Drive Special Count, All Chineae Faculty On Four Routes teachers will return from leave of 2500 Dividend absence. Miss Melissa Fouratte Cases This Week Appointed by Samuel Kinney Dr. Chih Menu, director of China Institute in America, baa or- Two buses, each to maintain two returns to Roosevejt Junior High nniwd «special courie tot tbe Westfield Adult School under the title School after a year in Scotland as Two more Westfield familes were Charles A. Doerr, 26 Fair Hill road has been elected general routes, will be provided by the affected by poliomyelitis this week, chairman of Weetfleld's 1949 United Campaign. Announcement of oj "CMna "> Tr»n»ition." It will be presented by eight Chinese lec- Somerset Bus Co. -

July 12, 2021

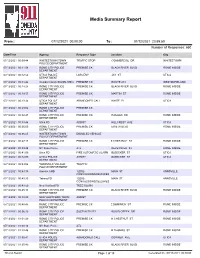

Media Summary Report From : 07/12/2021 00:00:00 To : 07/12/2021 23:59:59 Number of Responses: 660 Date/Time Agency Response Type Location City 07/12/2021 00:09:44 WHITESTOWN TOWN TRAFFIC STOP COMMERCIAL DR WHITESTOWN POLICE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:11:58 ROME CITY POLICE PREMISE CK BLACK RIVER BLVD ROME INSIDE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:12:52 UTICA POLICE LARCENY JAY ST UTICA DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:13:42 Oneida County Sheriffs Office PREMISE CK ROUTE 233 WESTMORELAND 07/12/2021 00:14:24 ROME CITY POLICE PREMISE CK BLACK RIVER BLVD ROME INSIDE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:19:57 ROME CITY POLICE PREMISE CK MARTIN ST ROME INSIDE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:23:34 UTICA POLICE ABANDONED CALL WHITE PL UTICA DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:29:02 ROME CITY POLICE PREMISE CK DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:32:47 ROME CITY POLICE PREMISE CK HANGAR RD ROME INSIDE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:33:46 Utica FD ASSIST HILLCREST AVE UTICA 07/12/2021 00:36:00 ROME CITY POLICE PREMISE CK ERIE W BLVD ROME INSIDE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:36:25 WHITESTOWN TOWN DISABLED VEHICLE POLICE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:37:17 ROME CITY POLICE PREMISE CK E CHESTNUT ST ROME INSIDE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:39:46 NY State Police ATL DEPEYSTER ST ROME INSIDE 07/12/2021 00:41:00 Utica FD FIRE AUTOMATIC ALARM BLEECKER ST UTICA 07/12/2021 00:42:00 UTICA POLICE ASSIST BLEECKER ST UTICA DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:43:06 YORKVILLE VILLAGE TRAFFIC POLICE DEPARTMENT 07/12/2021 00:43:35 Amcare AMB 12D02- MAIN ST ANNSVILLE CONVULSIONS/SEIZURES 07/12/2021 00:43:35 Taberg FD 12D02- MAIN ST ANNSVILLE CONVULSIONS/SEIZURES -

Buses from Grange Hill

Buses from Grange Hill 462 FR Limes Farm Estate O Copperfield GH D A LL L Hail & Ride MANOR ROA section AN E Manor Road C St. Winifred’s Church D Grange Hill M AN W A AR MANOR ROAD FO REN Grange Hill C RD T. LONG B WAY G R Manford Way G E Manford Primary School CRE RANGE E N SCEN Brocket Way T Manford Way Hainault Health Centre Destination finder Destination Bus routes Bus stops Destination Bus routes Bus stops B L Barkingside High Street 462 ,a ,c Limes Farm Estate Copperfield 462 ,b ,d Hainault Waverley Gardens Longwood Gardens 462 ,a ,c The Lowe Beehive Lane 462 ,a ,c M Brocket Way 362 ,c Manford Way 462 ,a ,c C Hainault Health Centre Chadwell Heath o High Road 362 ,c Manford Way 462 ,a ,c Manford Primary School Chadwell Heath Lane 362 ,c Manor Road St. Winifred's Church 462 ,b ,d Elmbridge Road New North Road Cranbrook Road for Valentines Park 462 ,a ,c Harbourer Road Marks Gate Billet Road 362 ,c E Eastern Avenue 462 ,a ,c N New North Road Harbourer Road 362 ,c Elmbridge Road 462 ,a ,c New North Road Yellow Pine Way 362 ,c F Buses from Grange Hill Fairlop 462 ,a ,c BusesR from Grange Hill Romford Road 362 ,c Forest Road New North Road Fremantle Road 462 ,a ,c Hainault Forest Golf Club for Fairlop Waters Yellow Pine Way Barkingside High Street Boulder Park Rose Lane Estate 362 ,c Forest Road 462 ,a ,c 462 for Fairlop Waters Boulder Park FR Limes Farm Estate W Copperfield O D Fullwell Cross for Leisure Centre 462 ,a ,c WhaleboneGH Lane North 362 ,c A Romford RoadLL L Hail & Ride G MANOR ROA section WhaleboneAN Lane North 362 ,c Gants Hill 462 ,a ,c Fairlop Romford Road Whalebone GroveE Manor Road Hainault Forest Golf Club H Woodford Avenue C 462 ,a ,c St. -

Directed by Nancy Carlin by George Bernard Shaw

CENTER REPERTORY COMPANY OF WALNUT CREEK Michael Butler, Artistic Director Scott Denison, Managing Director presents By George Bernard Shaw Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Kelly James Tighe Victoria Livingston-Hall Kurt Landisman Sound Designer Stage Manager Prop Master Lyle Barrere Gregg Rehrig* Christopher Kesel Wig Designer Judy Disbrow Cast Andy Gardner Maggie Mason Kendra Lee Oberhauser Gabriel Marin* Aaron Murphy Lisa Anne Porter* Craig Marker* Michael Ray Wisely* Directed by Nancy Carlin Margaret Lesher Theatre January 27 - February 25, 2012 Lesher Center for the Arts Season Season Partner Season Media Sponsor Foundation Sponsor Sponsor *Member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States The Lighting Designer is a member of United Scenic Artists Union The Director is a member of the Stage Directors and Choreographers Society Center REP is a member of Theatre Bay Area and Theatre Communications Group (TCG), The National Organization for the American Theatre CAST (in order of appearance) Craig Marker* (Captain Kendra Lee Oberhauser Bluntschli) has appeared at (Louka) is delighted to Catherine Petkoff ........................... Lisa Anne Porter* Center REP in The Mousetrap return to the Center REP Raina Petkoff .........................................Maggie Mason and The Marriage of Figaro. stage where she was last Louka .....................................Kendra Lee Oberhauser His Bay Area theater credits seen in Dracula (Mina Captain Bluntschli .................................Craig Marker* include The Glass Menagerie, Murray), Noises Off (Poppy) Russian Officer ............................ Andy Ryan Gardner Seagull, 9 Circles, Equivocation and The Women (various). Nicola ....................................................... Aaron Murphy and Bus Stop at Marin Theatre Company; The Circle Recent credits include: Reduction in Force and Major Petkoff ............................. -

Future First

Your Alumni Community An Alumni Community for Every School and College INTRODUCTION The Potential Future First’s vision is that every state Among the alumni of every school and college, school and college should be supported there is a whole range of inspiring career and education role models, volunteers, work by a thriving, engaged alumni experience providers, governors, donors, mentors community. and e-mentors. For generations, private schools and universities have effectively harnessed the talent, time and support that former students can share. Now, Future First is making it easy and inexpensive for state schools and colleges to do the same. Role Models Future First is a UK-registered charity that started when a group of former state school students began volunteering at their old school, helping CV give careers talks to young people who didn’t always have access to people in jobs at home. Volunteers Work Experience Governors Donors Mentors 2 Future First Your Alumni Community HOW IT WORKS Sign up Future First helps schools and colleges build alumni networks by offering the infrastructure and expertise that make it quick and easy to do so. We combine expert support in building, engaging and making the most of your network with an intelligent database platform that sits at the heart of the programme. We know how busy school and college life is, so our team of Networks Officers will work with you to make it as easy as possible. Future First schools and colleges have access to the following: Future First helps you sign up current leavers A secure, online database which allows you to filter and search alumni records and see how they’re keen to support; and former students who have left over the years. -

Project 3 Unit 3 Mock Test3

Put the verbs in the brackets into the correct tense. Use the past simple or past continuous tense. My friends saw me when I was waiting for my girlfriend. (see, wait) ________________________________________ 1. The teacher ____________ into the classroom when we _____________ football. (come, play) ________________________________________ 2. I ___________ my girlfriend while I ________________________________________ ___________ at university. (meet, study) 3. Mark ______________ home when it ___________ to rain. (walk, start) /6 . A detective is asking questions. Write the questions. What were you doing at 6 o´clock? ________________________________________ I was walking my dog at 6 o´clock. ________________________________________ 1. _____________________________________? ________________________________________ We were sitting on a bench. /6 2. ______________________________________? . Complete the sentences with the words from the box. I saw a beautiful girl. 3._____________________________________? wind water snow volcano A short skirt and a yellow Tshirt. lightning earthquake 4. ____________________________________? 1. It rained a lot but there was no ___________. She went into the restaurant. 2. The ____________________ destroyed a lot of 5. ____________________________________? houses. She was short and slim. 3. The _______________ exploded and there /5 came out a lot of stones and lava from the . These are pictures from yesterday. Write what mountain. happened. 4. Tornado is a kind of a strong ________________ which goes very quickly. 5. A flood is a lot of _________________. 6. During an avalanche a lot of _____________ goes down a mountain and destroys everything. /6 When the boy was playing football, he fell and he broke his leg. Correct the sentences. Change only 1 word in 1. When did Grange Hill start? ___________________________________ each sentence. -

Oklahoma Eastern Redcedar Registry - Landowners with Cedar Available

OKLAHOMA EASTERN REDCEDAR REGISTRY - LANDOWNERS WITH CEDAR AVAILABLE County First Last Street Address Address Line 2 City State Zip Code Phone Email Address Acres of cedar trees % cedar coverage average size Alfalfa Jim Early 820 N. Front St. Medford Oklahoma 73759 (580 ) 395-2753 [email protected] 2000 up to 25% 4 ft to 10 ft Beaver Arlene Broadie PO box 3096 Shawnee Oklahoma 74802 (405) 517-7311 [email protected] 800 over 75% 4 ft to 10 ft Blaine Tommy Anderson Rt 1 Box 89A Thomas Oklahoma 73669 (580) 819-0122 [email protected] 160 25 to 50% Over 10 ft Blaine Rick Payne 8890 N 2445 Rd Thomas Oklahoma 73669 (580) 614-1750 [email protected] 250 25 to 50% Over 10 ft Blaine R. B. Rosier 21210 N Council Rd Edmond Oklahoma 7.012 (405) 596-0777 [email protected] 160 25 to 50% 4 ft to 10 ft Blaine Dustin Kurtz 10901 San Lorenzo Dr Oklahoma City Oklahoma 73173 (405) 388-5630 [email protected] 320 25 to 50% 4 ft to 10 ft Bryan Laura Hider 711 3rd St Caddo Oklahoma 74729 (580) 920-3803 [email protected] 30 50 to 75% Over 10 ft Bryan Ronald Marshall 760 Lakeshore Durant Oklahoma 74701 (580) 924-0337 [email protected] 50-60 25 to 50% Over 10 ft Caddo Paul Buzbee 22126 County Road 1240 Gracemont Oklahoma 73042 (405) 933-2108 [email protected] 30 50 to 75% Over 10 ft Caddo Derek Cocheran P.O. BOX 812 CYRIL Oklahoma 73029 ((405)) 574--6606 [email protected] 120 25 to 50% Over 10 ft Caddo Curtis Constien 360 red Fork Clinton Oklahoma 73601 (580) 331-7299 [email protected] 40 over 75% Over 10 ft caddo Shirley Cornett 1847 Promenade Lane Xenia Ohio 45385 (937) 372-8800 [email protected] 10 50 to 75% 4 ft to 10 ft Caddo David Giesbrecht Rt 1 Box 2351 Lookeba Oklahoma 73053 (405) 542-7229 [email protected] 100 over 75% Over 10 ft Caddo Susan Granger 2617 Country Club Dt. -

Scott & Bailey 2 Wylie Interviews

Written by Sally Wainwright 2 PRODUCTION NOTES Introduction .........................................................................................Page 3 Regular characters .............................................................................Page 4 Interview with writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright ...................Page 5 Interview with co-creator Diane Taylor .............................................Page 8 Suranne Jones is D.C. Rachel Bailey ................................................Page 11 Lesley Sharp is D.C. Janet Scott .......................................................Page 14 Amelia Bullmore is D.C.I. Gill Murray ................................................Page 17 Nicholas Gleaves is D.S. Andy Roper ...............................................Page 20 Sean Maguire is P.C. Sean McCartney ..............................................Page 23 Lisa Riley is Nadia Hicks ....................................................................Page 26 Kevin Doyle is Geoff Hastings ...........................................................Page 28 3 INTRODUCTION Suranne Jones and Lesley Sharp resume their partnership in eight new compelling episodes of the northern-based crime drama Scott & Bailey. Acclaimed writer and co-creator Sally Wainwright has written the second series after once again joining forces with Consultancy Producer Diane Taylor, a retired Detective from Greater Manchester Police. Their unique partnership allows viewers and authentic look at the realities and responsibilities of working within -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

1 an AGE of KINGS (BBC TV, 1960) Things Have Moved on in Fifty Years

1 AN AGE OF KINGS (BBC TV, 1960) BBC VIDEO 5 disc set; ISBN 1-4198-7901-4, Region 1 only Tom Fleming, Robert Hardy Things have moved on in fifty years. In 1960 (I was sixteen), we didn’t have a television, and I had to prevail upon my school-friends to let me cycle round to their houses every alternate Thursday to watch this series. 1 Now, I can sit in my armchair and watch it straight through on my computer on DVD, with sound coming through the headphones. I count An Age of Kings as the single most important cultural event in my entire life, more important even than being in Trevor Nunn’s first-ever Shakespeare production ( Hamlet ) the previous year. It taught me what Shakespeare was about, and I’ve never forgotten it. Over ten years ago, seeing that it was on at the NFT, I went down to see some odd bits. Approaching Michael Hayes, the director, I said, “What you did here provided me with the single most important cultural event of my life”. He looked at me suspiciously: “You seem a bit young to say that”, he said, and turned away. I went up to Peter Dews, the producer: “What you did here provided me with the single most important cultural event of my life” – “Good!” he grunted, and turned away. So much for the creative team. Were they really as boring as that in 1960? (In fact Dews died shortly after our brief chat.) Paul Daneman said in an accompanying NFT lecture that the cast spent every morning talking, and didn’t start rehearsals till after lunch. -

Armchair Treasure Hunt 2014 Solution Compiled by BRUCE HINDSIGHT

Armchair Treasure Hunt 2014 Solution compiled by BRUCE HINDSIGHT Summary The puzzle has five principal parts: a genetic code, a quiz, a picture quiz, four sets of boxes establishing locations (‘bases’), and a jigsaw. The genetic code explains what to do with the solutions to the quiz questions: each answer (apart from the missing Q42) provides a letter pair and a fivecharacter sequence. The fivecharacter sequences yield a message explaining how to find the treasure site by intersecting two lines joining pairs of the ‘bases’. The letter pairs spell out acrostics confirming details of the four ‘bases’. In combination with the chromosome diagram on p.12, they also yield the final steps to the treasure. Pictures in circular vignettes, when identified, yield a oneone correspondence with the answers to the questions. Jigsaw pieces on the reverse of these vignettes can be assembled to discover a discouraging message (‘this is not the correct solution’), with one piece missing. The jigsaw can be resolved by putting the vignettes in order, boustrophedonstyle, using the numbering of the corresponding questions. The missing piece (corresponding to the treasure) is now in the shape of an X in location 42. Four of the vignettes, which also relate to the four ‘bases’, now line up in the jigsaw, creating lines which intersect at the missing piece. The puzzle is themed around deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas [Noel] Adams (whose initials are also DNA). The number 42 (the answer to “the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything”) variously represents the centromere of a chromosome and the location of the treasure. -

Harry Attacks the Press As Meghan Sues Mail on Sunday

Veteran newsman Sissons dead at 77 - page 3 California’s British Accent ™ - Since 1984 Saturday, October 5, 2019 • Number 1803 Always Free Harry attacks the press as Meghan sues Mail On Sunday n Prince says he can no longer be a “silent witness to her private suffering” THE TENSE relationship between Harry, Meghan and the British media took a turn for the worse this week, as it emerged that the Duchess plans to sue the Mail on Sunday. The legal action is acceptable, at any level. We individual. Pursuing legal a consequence of the won’t and can’t believe in action on this narrow basis newspaper’s decision to a world where there is no also gives the royals a publish a handwritten accountability for this. greater chance of success letter Meghan had sent to “Though this action may against DMG Media, her estranged father. not be the safe one, it is the formerly Associated The decision came right one … I’ve seen what Newspapers, which also as Prince Harry launched happens when someone owns the Daily Mail and an extraordinary and I love is commoditized to MailOnline – both of which highly personal attack on the point that they are no have run a substantial the British tabloid press and longer treated or seen as a number of stories about its treatment of his wife, real person. Meghan. PRINCE HARRY: “I’ve seen what happens when someone I love is commoditized saying he could no longer The Mail on Sunday has to the point that they are no longer treated or seen as a real person.” be a “silent witness to her embarrassing stories run multiple embarrassing private suffering”.