Rebirth, Resounding, Recreation: Making Seventies Rock in the 21St Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

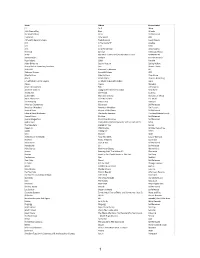

Pandoras Box CD-List 06-2006 Short

Pandoras Box CD-list 06-2006 short.xls Form ARTIST TITLE year No Label price CD 2066 & THEN Reflections !! 1971 SB 025 Second Battle 15,00 € CD 3 HUEREL 3 HUEREL 1970-75 WPC6 8462 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3 HUEREL Huerel Arisivi 1970-75 WPC6 8463 World Psychedelic 17,00 € CD 3SPEED AUTOMATIC no man's land 2004 SA 333 Nasoni 15,00 € CD 49 th PARALLELL 49 th PARALLELL 1969 Flashback 008 Flashback 11,90 € CD 49TH PARALLEL 49TH PARALLEL 1969 PACELN 48 Lion / Pacemaker 17,90 € CD 50 FOOT HOSE Cauldron 1968 RRCD 141 Radioactive 14,90 € CD 7 th TEMPLE Under the burning sun 1978 RRCD 084 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A - AUSTR Music from holy Ground 1970 KSG 014 Kissing Spell 19,95 € CD A BREATH OF FRESH AIR A BREATH OF FRESH AIR 196 RRCD 076 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A CID SYMPHONY FISCHBACH AND EWING - (21966CD) -67 GF-135 Gear Fab 14,90 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER A Foot in coldwater 1972 AGEK-2158 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER All around us 1973 AGEK-2160 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 1 1973 BEBBD 25 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - Vol. 2 1973 BEBBD 26 Bei 9,95 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER The second foot in coldwater 1973 AGEK-2159 Unidisc 15,00 € CD A FOOT IN COLDWATER best of - (2CD) 1972-73 AGEK2-2161 Unidisc 17,90 € CD A JOINT EFFORT FINAL EFFORT 1968 RRCD 153 Radioactive 14,90 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy 1968 FB 11 Flashback 15,00 € CD A PASSING FANCY A Passing Fancy - (Digip.) 1968 PACE-034 Pacemaker 15,90 € CD AARDVARK Aardvark 1970 SRMC 0056 Si-Wan 19,95 € CD AARDVARK AARDVARK - (lim. -

Som Musikprojekt Har Dungen Pågått Sedan 1998. Det Startades Av Gustav Ejstes Som Sedan Dess Skriver Och Arrangerar Musiken

Dungen Tio Bitar (SUBCD24) Som musikprojekt har Dungen pågått sedan 1998. Det startades av Gustav Ejstes som sedan dess skriver och arrangerar musiken. På så vis är Dungen en persons verk; det är en person som skapar låtarna. Men Dungen hade inte varit det det är om det inte vore för musikaliska möten. Ett av de möten som fått en central betydelse för hur Dungen låter är det med gitarristen Reine Fiske. Gustav och Reine träffades redan ett par år efter projektets födelse och sedan dess har gitarristens påverkan på låtarna bara blivit större. ”Reine Fiske har ett säreget tonspråk och uttryck”, säger Gustav. ”Han har ett sätt att traktera elgitarren som inte många har.” Det sättet ligger mycket nära Gustavs ljudmässiga vision och det har satt sina avtryck. Allra helst i den nya skivan. Om Gustav spelade mer själv på de förra albumen (Dungen, Stadsvandringar, Ta det lugnt) - gitarr, bas, trummor, flöjt, blev det i skapelseprocessen av den senaste plattan än mer av Reines bas och gitarr. Grunden till låtarna lägger de tillsammans. Gustav spelar en del och instruerar, Reine spelar. Efter det bjuder Gustav in andra musiker för, som han säger, ”resultatets bästa”. Det sättet jobbar han helst på, med en person i taget. ”Det fungerar i någon mening som i hip-hopen. En producent ligger ofta bakom allt och i det här fallet är jag producenten.” Inför arbetet med den nya skivan gjorde Gustav som med det förra albumet. Han isolerade sig några månader i ett hus i Småland i södra Sverige; för att kunna fokusera, ”för att hålla influenserna på avstånd”. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

2015 Year in Review

Ar#st Album Record Label !!! As If Warp 11th Dream Day Beet Atlan5c The 4onthefloor All In Self-Released 7 Seconds New Wind BYO A Place To Bury StranGers Transfixia5on Dead Oceans A.F.I. A Fire Inside EP Adeline A.F.I. A.F.I. Nitro A.F.I. Sing The Sorrow Dreamworks The Acid Liminal Infec5ous Music ACTN My Flesh is Weakness/So God Damn Cold Self-Released Tarmac Adam In Place Onesize Records Ryan Adams 1989 Pax AM Adler & Hearne Second Nature SprinG Hollow Aesop Rock & Homeboy Sandman Lice Stones Throw AL 35510 Presence In Absence BC Alabama Shakes Sound & Colour ATO Alberta Cross Alberta Cross Dine Alone Alex G Beach Music Domino Recording Jim Alfredson's Dirty FinGers A Tribute to Big John Pa^on Big O Algiers Algiers Matador Alison Wonderland Run Astralwerks All Them Witches DyinG Surfer Meets His Maker New West All We Are Self Titled Domino Jackie Allen My Favorite Color Hans Strum Music AM & Shawn Lee Celes5al Electric ESL Music The AmazinG Picture You Par5san American Scarecrows Yesteryear Self Released American Wrestlers American Wrestlers Fat Possum Ancient River Keeper of the Dawn Self-Released Edward David Anderson The Loxley Sessions The Roayl Potato Family Animal Hours Do Over Self-Released Animal Magne5sm Black River Rainbow Self Released Aphex Twin Computer Controlled Acous5c Instruments Part 2 Warp The Aquadolls Stoked On You BurGer Aqueduct Wild KniGhts Wichita RecordinGs Aquilo CallinG Me B3SCI Arca Mutant Mute Architecture In Helsinki Now And 4EVA Casual Workout The Arcs Yours, Dreamily Nonesuch Arise Roots Love & War Self-Released Astrobeard S/T Self-Relesed Atlas Genius Inanimate Objects Warner Bros. -

New Blood’: a Contemporary GIM Programme Svein Fuglestad

Approaches: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Music Therapy | Special Issue 9 (2) 2017 SPECIAL ISSUE Guided Imagery and Music: Contemporary European perspectives and developments Article ‘New Blood’: A contemporary GIM programme Svein Fuglestad ABSTRACT This article is a presentation of a new contemporary Guided Imagery and Music (GIM) program based on orchestral re-recordings of various tracks by the English pop and rock musician Peter Gabriel. The intention is to share with the GIM community the author’s own experiences and perspectives using this music from the popular music genre with individual clients. The different pieces in the music programme are presented and described using the MIA intensity profile, Hevner’s Mood Wheel and the taxonomy of music. Whether the use of non-classical music is consistent with the individual form of the Bonny Method of GIM will be discussed, together with the potential advantages of repetitions and recognitions due to simplicity in structure, form and harmonies in building safety for clients within a therapeutic setting. KEYWORDS Guided Imagery and Music, new GIM programme, non-classical music in GIM, receptive music therapy, music and imagery, Peter Gabriel Svein Fuglestad is an Associate Professor at Oslo and Akershus University of Applied Sciences, Faculty of Social Sciences, Child Welfare programme. He is an AMI-Fellow/BMGIM therapist (2006) and cand. philol. in musicology (1996), and has been practising GIM with people affected by HIV/AIDS, sexually abused men, and female victims of incest. Fuglestad was GIM therapist in the Norwegian Research Council project Music, Motion, and Emotion. He is a singer and a musician. -

Myspace.Com - - 43 - Male - PHILAD

MySpace.com - WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM - 43 - Male - PHILAD... http://www.myspace.com/recordcastle Sponsored Links Gear Ink JazznBlues Tees Largest selection of jazz and blues t-shirts available. Over 100 styles www.gearink.com WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM is in your extended "it's an abomination that we are in an network. obama nation ... ron view more paul 2012 ... balance the budget and bring back tube WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Latest Blog Entry [ Subscribe to this Blog ] amps" [View All Blog Entries ] Male 43 years old PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Blurbs United States About me: I have been an avid music collector since I was a kid. I ran a store for 20 years and now trade online. Last Login: 4/24/2009 I BUY PHONOGRAPH RECORDS ( 33 lp albums / 45 rpms / 78s ), COMPACT DISCS, DVD'S, CONCERT MEMORABILIA, VINTAGE POSTERS, BEATLES ITEMS, KISS ITEMS & More Mood: electric View My: Pics | Videos | Playlists Especially seeking Private Pressings / Psychedelic / Rockabilly / Be Bop & Avant Garde Jazz / Punk / Obscure '60s Funk & Soul Records / Original Contacting WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM concert posters 1950's & 1960's era / Original Beatles memorabilia I Offer A Professional Buying Service Of Music Items * LPs 45s 78s CDS DVDS Posters Beatles Etc.. Private Collections ** Industry Contacts ** Estates Large Collections / Warehouse finds ***** PAYMENT IN CASH ***** Over 20 Years experience buying collections MySpace URL: www.myspace.com/recordcastle I pay more for High Quality Collections In Excellent condition Let's Discuss What You May Have For Sale Call Or Email - 717 209 0797 Will Pick Up in Bucks County / Delaware County / Montgomery County / Philadelphia / South Jersey / Lancaster County / Berks County I travel the country for huge collections Print This Page - When You Are Ready To Sell Let Me Make An Offer ----------------------------------------------------------- Who I'd like to meet: WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM's Friend Space (Top 4) WWW.RECORDCASTLE.COM has 57 friends. -

Ane Brun Mit Neuen Songs Auf Tournee

Ane Brun mit neuen Songs auf Tournee mn. Die Liedermacherin Ane Brun wurde 1976 als Ane Brunvoll in Norwegen geboren. Mit 21 Jahren endeckte sie die Gitarre und versuchte sich als Stras- senmusikerin in Spanien. Danach beschloss sie das Musikmachen ernsthaft zu betreiben. Seit ihrem Umzug nach Schweden im Jahr 2000, arbeitete sie sich musikalisch hoch, von den Gigs in kleinen Pubs bis hinein in die grossen Stadien. Bereits 2005 stand sie im Wembley Stadion. 2010 spielte Ane Brun im Vorprogramm von Peter Gabriels New-Blood-Tour. Sie war auch als Backgroundsängerin tätig und übernahm bei „Don’t Give Up“ den Gesangspart von Kate Bush. Im September 2011 veröffentlichte Ane Brun das Album „It All Starts with One“. Derzeit lebt sie im schwedischen Stockholm und betreibt ihr eigenes Plattenlabel DetErMi- ne Records (= das sind meine Platten). Das alles tönt wunderbar, ist es auch. Doch Ane Brun zahlt einen hohen Preis. Ihr Immun- system dreht seit 1998 völlig durch. Lupus heisst diese tückische Krankheit. Brun muss mit Schmerzen leben. Hautveränderungen, Haarausfall, Sonnenallergie, Fieber, Arthritis sind ihre täglichen Begleiter. Und Angst. Es gibt kein Heilmittel, bei jeder betroffenen Person verläuft diese Krankheit anders. Linderung bringt allenfalls Kortison - mit beträchtlichen Nebenwirkungen. Ane Brun verbrachte viel Zeit im Spital, lag monatelang arbeitsunfähig zuhause. Eine wei- tere Tour 2012 mit Peter Gabriel musste sie absagen. Doch die Krankheit hat sie nicht besiegt, ihre Kreativität nicht vernichtet. Seit ihrem Debutalbum „Spending time with Morgan“ veröffentlichte sie bereits sechs Studioalben, ein Live-Album und eine Best of Collection. Was bei Ane Brun besticht, ist ihre Stimme, diese filigrane, intensive und klare Stimme. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Order Form Full

JAZZ ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL ADDERLEY, CANNONBALL SOMETHIN' ELSE BLUE NOTE RM112.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS LOUIS ARMSTRONG PLAYS W.C. HANDY PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 ARMSTRONG, LOUIS & DUKE ELLINGTON THE GREAT REUNION (180 GR) PARLOPHONE RM124.00 AYLER, ALBERT LIVE IN FRANCE JULY 25, 1970 B13 RM136.00 BAKER, CHET DAYBREAK (180 GR) STEEPLECHASE RM139.00 BAKER, CHET IT COULD HAPPEN TO YOU RIVERSIDE RM119.00 BAKER, CHET SINGS & STRINGS VINYL PASSION RM146.00 BAKER, CHET THE LYRICAL TRUMPET OF CHET JAZZ WAX RM134.00 BAKER, CHET WITH STRINGS (180 GR) MUSIC ON VINYL RM155.00 BERRY, OVERTON T.O.B.E. + LIVE AT THE DOUBLET LIGHT 1/T ATTIC RM124.00 BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY BIG BAD VOODOO DADDY (PURPLE VINYL) LONESTAR RECORDS RM115.00 BLAKEY, ART 3 BLIND MICE UNITED ARTISTS RM95.00 BROETZMANN, PETER FULL BLAST JAZZWERKSTATT RM95.00 BRUBECK, DAVE THE ESSENTIAL DAVE BRUBECK COLUMBIA RM146.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - OCTET DAVE BRUBECK OCTET FANTASY RM119.00 BRUBECK, DAVE - QUARTET BRUBECK TIME DOXY RM125.00 BRUUT! MAD PACK (180 GR WHITE) MUSIC ON VINYL RM149.00 BUCKSHOT LEFONQUE MUSIC EVOLUTION MUSIC ON VINYL RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY MIDNIGHT BLUE (MONO) (200 GR) CLASSIC RECORDS RM147.00 BURRELL, KENNY WEAVER OF DREAMS (180 GR) WAX TIME RM138.00 BYRD, DONALD BLACK BYRD BLUE NOTE RM112.00 CHERRY, DON MU (FIRST PART) (180 GR) BYG ACTUEL RM95.00 CLAYTON, BUCK HOW HI THE FI PURE PLEASURE RM188.00 COLE, NAT KING PENTHOUSE SERENADE PURE PLEASURE RM157.00 COLEMAN, ORNETTE AT THE TOWN HALL, DECEMBER 1962 WAX LOVE RM107.00 COLTRANE, ALICE JOURNEY IN SATCHIDANANDA (180 GR) IMPULSE -

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists

Music Globally Protected Marks List (GPML) Music Brands & Music Artists © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document cannot be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. 1 Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in established music trade publications. Please provide DotMusic with evidence that such criteria is met at [email protected] if you would like your artist name of brand name to be included in the DotMusic GPML. GLOBALLY PROTECTED MARKS LIST (GPML) - MUSIC ARTISTS DOTMUSIC (.MUSIC) ? and the Mysterians 10 Years 10,000 Maniacs © 2012 - DotMusic Limited (.MUSIC™). All Rights Reserved. DotMusic reserves the right to modify this Document .This Document 10cc can not be distributed, modified or reproduced in whole or in part 12 Stones without the prior expressed permission of DotMusic. Visit 13th Floor Elevators www.music.us 1910 Fruitgum Co. 2 Unlimited Disclaimer: This GPML Document is subject to change. Only artists exceeding 1 million units in sales of global digital and physical units are eligible for inclusion in the GPML. 3 Doors Down Brands are eligible if they are globally-recognized and have been mentioned in 30 Seconds to Mars established music trade publications. Please -

Am. Singer/Songwriter,Flott.Covret Av Bl.A Spooky.Tooth,J.Driscoll. Utgitt I 1993

ARTIST / BANDNAVN ALBUM TITTEL UTG.ÅR LABEL/ KATAL.NR. LAND LP A ATCO REC7567- AC/DC BACK IN BLACK 1995 EUR CD 92418-2 ACKLES, DAVID FIVE & DIME 2004 RAVENREC. AUST. CD Am. singer/songwriter,flott.Covret av bl.a Spooky.Tooth,J.Driscoll. Utgitt i 1993. Cd utg. fra 2004 XL RECORDINGS ADELE 21 2011 EUR CD XLLP 520 ADELE 25 2015 XLCD 740 EUR CD ADIEMUS SONGS OF SANCTUARY 1995 CDVE 925 HOL CD Prosjektet til ex Soft Machine medlem Karl Jenkins. Middelalderstemnig og mye flott koring. AEROSMITH PUMP 1989 GEFFEN RECORDS USA CD Med Linda Hoyle på flott vocal, Mo Foster, Mike Jupp.Cover av Keef. Høy verdi på original vinyl AFFINITY AFFINITY 1970 VERTIGO UK CD Vertigo swirl. AFTER CRYING OVERGROUND MUSIC 1990 ROCK SYMPHONY EUR CD Bulgarsk progband, veldig bra. Tysk eksperimentell /elektronisk /prog musikk. Østen insirert album etter Egyptbesøk. Lp utgitt AGITATION FREE MALESCH 2008 SPV 42782 GER CD 1972. AIR MOON SAFARI 1998 CDV 2848 EUR CD Frank duo, mye keyboard og synthes. VIRGIN 72435 966002 AIR TALKIE WALKIE 2004 EUR CD 8 ALBION BAND ALBION SUNRISE 1994-1999 2004 CASTLE MUSIC UK CDX2 Britisk folkrock med bl.a A.Hutchings,S.Nicol ex.Fairport Convention ALBION BAND M/ S.COLLINS NO ROSES 2004 CASTLE MUSIC UK CD Britisk folk rock. Opprinnelig på Pegasus Rec. I 1971. CD utg fra 2004. Shirley Collins på vocal. ALICE IN CHAINS DIRT 1992 COLOMBIA USA CD Godt album, flere gode låter, bl.a Down in a hole. ALICE IN CHAINS SAP 1992 COLOMBIA USA CD Ep utgivelse med 4 sterke låter, Brother, Got me wrong, Right turn og I am inside ALICE IN CHAINS ALICE IN CHAINS 1995 COLOMBIA USA CD Tungt, smådystert og bra. -

Psicodelia-1.Pdf

CÍRCULO DE BELLAS ARTES EXPOSICIÓN presidente comisario Juan Miguel Hernández León Zdenek Primus director área de Artes Plásticas del CBA Juan Barja Laura Manzano subdirectora coordinación Lidija Šircelj Virginia Gómez directora de proyectos y relaciones externas producción gráfica Pilar García Velasco SAR directora de programación montaje Laura Manzano Méndez Área de Mantenimiento del CBA directora de publicaciones seguro Carolina del Olmo Vadok Arte directora económico-financiera transporte Isabel Pozo Dobel Art CATÁLOGO CENTRO CHECO área de edición del CBA director Carolina del Olmo Stanislav Škoda Elena Iglesias Serna Hara Hernández subdirectora Iveta Gonzalezová proyecto gráfico y diseño de cubierta Estudio Joaquín Gallego impresión Brizzolis, arte en gráficas © Círculo de Bellas Artes, 2018 Alcalá, 42. 28014 Madrid www.circulobellasartes.com © de los textos: sus autores © de las fotografías y digitalización: Hana Hamplová y Marcel Rozhon Zdenek Primus, comisario de la exposición, quiere agradecer de corazón a todos aquellos que le han ayudado: Jaroslav Bezdeˇ k, Jaroslav Fajgl, Jaroslav Foršt, Karel Habal, Pavel Jasanský, Eric King, Ivo Marek, Ray Mortenson, Aleš Novák, Jaroslav Novotný, Jan Oravec, Jan Placák, Václav Prošek, Pavel Rajcˇ an, Jirˇ í Rybárˇ , Tomáš Sanetrník, Ota Semotán, Jaroslav Šteˇ drý, Pavel Váneˇ , David Webr y Vladimír Zelenka. También a la Biblioteca Nacional de la República Checa y, por supuesto, al PopMuseum de Praga, en concreto, a Radek Diestler. ISBN: 978-84-947752-8-4 Depósito Legal: M-31906-2018 [COLECCIÓN DE ZDENEK PRIMUS] Si pensamos en contracultura juvenil, las primeras imágenes que se nos vienen a la mente seguramente incluyen grupos de jóvenes melenudos, marihuana, LSD y música, mucha música.