Arrack, Toddy and Ceylonese Nationalism: Some Observations on the Temperance L'v1ovement, 19 J 2 - 1921

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facets-Of-Modern-Ceylon-History-Through-The-Letters-Of-Jeronis-Pieris.Pdf

FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS BY MICHAEL ROBERT Hannadige Jeronis Pieris (1829-1894) was educated at the Colombo Academy and thereafter joined his in-laws, the brothers Jeronis and Susew de Soysa, as a manager of their ventures in the Kandyan highlands. Arrack-renter, trader, plantation owner, philanthro- pist and man of letters, his career pro- vides fascinating sidelights on the social and economic history of British Ceylon. Using Jeronis Pieris's letters as a point of departure and assisted by the stock of knowledge he has gather- ed during his researches into the is- land's history, the author analyses several facets of colonial history: the foundations of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the nineteenth century; the process of Wes- ternisation and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance no. 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land bet- ween coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan dis- tricts. This analysis is threaded by in- formation on the Hannadige- Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families and by attention to the various sources available to the historians of nineteenth century Ceylon. FACETS OF MODERN CEYLON HISTORY THROUGH THE LETTERS OF JERONIS PIERIS MICHAEL ROBERTS HANSA PUBLISHERS LIMITED COLOMBO - 3, SKI LANKA (CEYLON) 4975 FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1975 This book is copyright. -

Baila and Sydney Sri Lankans

Public Postures, Private Positions: Baila and Sydney Sri Lankans Gina Ismene Shenaz Chitty A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Contemporary Music Studies Division of Humanities Macquarie University Sydney, Australia November 2005 © Copyright TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF F IG U R E S.......................................................................................................................................................................... II SU M M A R Y ......................................................................................................................................................................................Ill CER TIFIC ATIO N ...........................................................................................................................................................................IV A CK NO W LED GEM EN TS............................................................................................................................................................V PERSON AL PR EFA C E................................................................................................................................................................ VI INTRODUCTION: SOCIAL HISTORY OF BAILA 8 Anglicisation of the Sri Lankan elite .................... ............. 21 The English Gaze ..................................................................... 24 Miscegenation and Baila............................................................ -

Cardinal Refuses to Meet Ministers

www.themorning.lk Late City VOL 01 | NO 21 | Rs. 30.00 { MONDAY } MONDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 2021 LEADING NAMES ‘NOTEWORTHY’ DROPPED FOR WITH FITNESS ISSUES DR. LALANATH DE SILVA AYURVEDIC ‘OUR COVID RESPONSE CENTRES OPENING HAS LACKED PROPER OVERSEAS DECISION MAKING’ »SEE PAGE 16 »SEE PAGE 7 »SEE PAGE 6 »SEE PAGE 11 Madrasa Schools Cardinal refuses to be regulated to meet Ministers z To come under State Ministry of Dhamma z Aimed at promoting z z Schools and Bhikkhu Education religious coexistence No meeting until receipt Govt. delegation hoped BY HIRANYADA DEWASIRI under separate departments Religious and Cultural Affairs, of report: Cardinal to reassure Cardinal that fall under the umbrella of and Education. BY DINITHA RATHNAYAKE to see it at the beginning of All religious schools in the the Ministry of Buddhasasana, “This decision has been taken February. country, including Madrasas, are Religious, and Cultural Affairs. to provide religious education The Archbishop of Colombo, Malcolm Cardinal Ranjith State Minister of Coconut, to be registered and regulated Speaking to The Morning on whilst promoting religious has refused a request for a meeting by the Catholic Kithul and Palmyrah Cultivation under the State Ministry of Thursday (18), State Minister co-existence. Nobody wants Ministers and members of Parliament representing the Promotion and Related Industrial Dhamma Schools, Bhikkhu of Dhamma Schools, Bhikkhu extremism. Plans to develop Government, The Morning learnt yesterday (21). Product Manufacturing, and Education, Pirivenas, and -

Sri Lanka's Human Rights Crisis

SRI LANKA’S HUMAN RIGHTS CRISIS Asia Report N°135 – 14 June 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................ i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. HOW NOT TO FIGHT AN INSURGENCY ............................................................... 2 III. A SHORT HISTORY OF IMPUNITY......................................................................... 4 A. THE FAILURE OF THE JUDICIAL SYSTEM...................................................................................4 B. COMMISSIONS OF INQUIRY......................................................................................................5 C. THE CEASEFIRE AND HUMAN RIGHTS......................................................................................6 IV. HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE NEW WAR............................................................... 7 A. CIVILIANS AND WARFARE ......................................................................................................7 B. MASSACRES...........................................................................................................................8 C. EXTRAJUDICIAL KILLINGS ......................................................................................................9 D. THE DISAPPEARED ...............................................................................................................10 E. ABDUCTIONS FOR RANSOM...................................................................................................11 -

PDF995, Job 2

MONITORING FACTORS AFFECTING THE SRI LANKAN PEACE PROCESS CLUSTER REPORT FIRST QUARTERLY FEBRUARY 2006 œ APRIL 2006 CENTRE FOR POLICY ALTERNATIVES 0 TABLE OF CONTENTS CLUSTER Page Number PEACE TALKS AND NEGOTIATIONS CLUSTER.................................................... 2 POLITICAL ENVIRONM ENT CLUSTER.....................................................................13 SECURITY CLUSTER.............................................................................................................23 LEGAL & CONSTIIUTIONAL CLUSTER......................................................................46 ECONOM ICS CLUSTER.........................................................................................................51 RELIEF, REHABILITATION & RECONSTRUCTION CLUSTER......................61 PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS & SOCIAL ATTITUDES CLUSTER................................70 M EDIA CLUSTER.......................................................................................................................76. ENDNOTES.....… … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … … ..84 M ETHODOLOGY The Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA) has conducted the project “Monitoring the Factors Affecting the Peace Process” since 2005. The output of this project is a series of Quarterly Reports. This is the fifth of such reports. It should be noted that this Quarterly Report covers the months of February, March and April. Having identified a number of key factors that impact the peace process, they have been monitored observing change or stasis through -

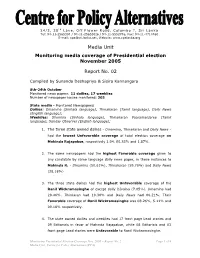

Monitoring Media Coverage of Presidential Election November 2005

24/2, 28t h La n e , Off Flowe r Roa d , Colom bo 7, Sri La n ka Tel: 94-11-2565304 / 94-11-256530z6 / 94-11-5552746, Fax: 94-11-4714460 E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.cpalanka.org Media Unit Monitoring media coverage of Presidential election November 2005 Report No. 02 Compiled by Sunanda Deshapriya & Sisira Kannangara 8th-24th October Monitored news papers: 11 dailies, 17 weeklies Number of newspaper issues monitored: 205 State media - Monitored Newspapers: Dailies: Dinamina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran (Tamil language), Daily News (English language); W eeklies: Silumina (Sinhala language), Thinakaran Vaaramanjaree (Tamil language), Sunday Observer (English language); 1. The three state owned dailies - Dinamina, Thinakaran and Daily News - had the lowest Unfavorable coverage of total election coverage on Mahinda Rajapakse, respectively 1.04. 00.33% and 1.87%. 2. The same newspapers had the highest Favorable coverage given to any candidate by same language daily news paper, in these instances to Mahinda R. - Dinamina (50.61%), Thinakaran (59.70%) and Daily News (38.18%) 3. The three state dailies had the highest Unfavorable coverage of the Ranil W ickramasinghe of except daily DIvaina (7.05%). Dinamina had 29.46%. Thinkaran had 10.30% and Daily News had 06.21%. Their Favorable coverage of Ranil W ickramasinghe was 08.26%, 5.11% and 09.18% respectively. 4. The state owned dailies and weeklies had 17 front page Lead stories and 09 Editorials in favor of Mahinda Rajapakse, while 08 Editorials and 03 front page Lead stories were Unfavorable to Ranil Wickramasinghe. Monitoring Presidential Election Coverage Nov. -

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times

Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert PhD 2016 Chatting Sri Lanka: Powerful Communications in Colonial Times Justin Siefert A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, Politics and Philosophy Manchester Metropolitan University 2016 Abstract: The thesis argues that the telephone had a significant impact upon colonial society in Sri Lanka. In the emergence and expansion of a telephone network two phases can be distinguished: in the first phase (1880-1914), the government began to construct telephone networks in Colombo and other major towns, and built trunk lines between them. Simultaneously, planters began to establish and run local telephone networks in the planting districts. In this initial period, Sri Lanka’s emerging telephone network owed its construction, financing and running mostly to the planting community. The telephone was a ‘tool of the Empire’ only in the sense that the government eventually joined forces with the influential planting and commercial communities, including many members of the indigenous elite, who had demanded telephone services for their own purposes. However, during the second phase (1919-1939), as more and more telephone networks emerged in the planting districts, government became more proactive in the construction of an island-wide telephone network, which then reflected colonial hierarchies and power structures. Finally in 1935, Sri Lanka was connected to the Empire’s international telephone network. One of the core challenges for this pioneer work is of methodological nature: a telephone call leaves no written or oral source behind. -

Media Freedom in Post War Sri Lanka and Its Impact on the Reconciliation Process

Reuters Institute Fellowship Paper University of Oxford MEDIA FREEDOM IN POST WAR SRI LANKA AND ITS IMPACT ON THE RECONCILIATION PROCESS By Swaminathan Natarajan Trinity Term 2012 Sponsor: BBC Media Action Page 1 of 41 Page 2 of 41 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I would like to thank James Painter, Head of the Journalism Programme and the entire staff of the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism for their help and support. I am grateful to BBC New Media Action for sponsoring me, and to its former Programme Officer Tirthankar Bandyopadhyay, for letting me know about this wonderful opportunity and encouraging me all the way. My supervisor Dr Sujit Sivasundaram of Cambridge University provided academic insights which were very valuable for my research paper. I place on record my appreciation to all those who participated in the survey and interviews. I would like to thank my colleagues in the BBC, Chandana Keerthi Bandara, Charles Haviland, Wimalasena Hewage, Saroj Pathirana, Poopalaratnam Seevagan, Ponniah Manickavasagam and my good friend Karunakaran (former Colombo correspondent of the BBC Tamil Service) for their help. Special thanks to my parents and sisters and all my fellow journalist fellows. Finally to Marianne Landzettel (BBC World Service News) for helping me by patiently proof reading and revising this paper. Page 3 of 41 Table of Contents 1 Overview ......................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Challenges to Press Freedom -

South Asian Studies | Subject Catalog (PDF)

South Asian Studies Catalog of Microform (Research Collections, Serials, and Dissertations) http://www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/collections/rc-search.shtml [email protected] 800.521.0600 ext. 2793 or 734.761.4700 ext. 2793 USC027 -03 updated October 2009 Table of Contents About This Catalog ............................................................................................... 3 The Advantages of Microform ........................................................................... 4 Research Collections............................................................................................. 5 Annual Reports of the World‘s Central Banks ..............................................................................................6 Asia: ―E‖ Reports for Asia from the United Society for the Propagation of the Gospel* ........................6 Asian Studies Conference Papers....................................................................................................................6 Great Britain Board of Trade/Overseas Department Economic Surveys..................................................7 Hakluyt Society, Extra Series, Vols. 1-12* .......................................................................................................7 Human Rights Watch Publications .................................................................................................................7 HRAF: Human Relations Area Files ...............................................................................................................8 -

The Old Order Changeth': the Aborted Evolution

‗THE OLD ORDER CHANGETH‘: THE ABORTED EVOLUTION OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE, 1917-1931 A Dissertation by SEAN PATRICK KELLY Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, R.J.Q. Adams Committee Members, Troy Bickham Rebecca Hartkopf Schloss Anthony Stranges Peter Hugill Head of Department, David Vaught August 2014 Major Subject: History Copyright 2014 Sean Patrick Kelly ABSTRACT In the aftermath of the Great War (1914-18), Britons could, arguably for the first time since 1763, look to the immediate future without worrying about the rise of an anti- British coalition of European states hungry for colonial spoils. Yet the shadow cast by the apparent ease with which the United States rose to global dominance after 1940 has masked the complexity and uncertainty inherent in what turned out to be the last decades of the British Empire. Historians of British international history have long recognised that the 1920s were a period of adjustment to a new world, not simply the precursor to the disastrous (in hindsight) 1930s. As late as the eve of the Second World War, prominent colonial nationalists lamented that the end of Empire remained impossible to foresee. Britons, nevertheless, recognised that the Great War had laid bare the need to modernise the archaic, Victorian-style imperialism denounced by The Times, amongst others. Part I details the attempts to create a ‗New Way of Empire‘ before examining two congruent efforts to integrate Britain‘s self-governing Dominions into the very heart of British political life. -

A Case Study of Sri Lankan Media

C olonials, bourgeoisies and media dynasties: A case study of Sri Lankan media. Abstract: Despite enjoying nearly two centuries of news media, Sri Lanka has been slow to adopt western liberalist concepts of free media, and the print medium which has been the dominant format of news has remained largely in the hands of a select few – essentially three major newspaper groups related to each other by blood or marriage. However the arrival of television and the change in electronic media ownership laws have enabled a number of ‘independent’ actors to enter the Sri Lankan media scene. The newcomers have thus been able to challenge the traditional and incestuous bourgeois hold on media control and agenda setting. This paper outlines the development of news media in Sri Lanka, and attempts to trace the changes in the media ownership and audience. It follows the development of media from the establishment of the first state-sanctioned newspaper to the budding FM radio stations that appear to have achieved the seemingly impossible – namely snatching media control from the Wijewardene, Senanayake, Jayawardene, Wickremasinghe, Bandaranaike bourgeoisie family nexus. Linda Brady Central Queensland University ejournalist.au.com©2005 Central Queensland University 1 Introduction: Media as an imprint on the tapestry of Ceylonese political evolution. The former British colony of Ceylon has a long history of media, dating back to the publication of the first Dutch Prayer Book in 1737 - under the patronage of Ceylon’s Dutch governor Gustaaf Willem Baron van Imhoff (1736-39), and the advent of the ‘newspaper’ by the British in 1833. By the 1920’s the island nation was finding strength as a pioneer in Asian radio but subsequently became a relative latecomer to television by the time it was introduced to the island in the late1970’s. -

January 8, 2012 Statement by Sonali Samarasinghe Journalist in Exile and Widow of Sri Lankan Editor Lasantha Wickrematunge on Hi

January 8, 2012 Statement by Sonali Samarasinghe Journalist in Exile and Widow of Sri Lankan editor Lasantha Wickrematunge on his third death anniversary Sri Lanka’s democratic institutions have metastasized into something dangerous Today (January 8) marks the third death anniversary of Lasantha Wickrematunge a human rights journalist from Sri Lanka who fought fearlessly for the freedom of the press and relentlessly pursued what he believed was right. On January 8, 2009 he was brutally murdered by the Sri Lankan authorities for his journalism. Three years after Lasantha’s brutal murder despite the vapid assurances of the Rajapakse regime to the international community, Sri Lanka has turned into a lawless state of abductions, rape and murder with at least two of these incidents taking place in the New Year. Concentration of power and finances Even as there is an overwhelming concentration of power and finances in the ruling family, every one of Sri Lanka’s democratic institutions has metastasized into something dangerous and poisonous. Christmas day was marred by the brutal murder in the South of Sri Lanka, of a British tourist Kuram Shaikah Zaman – a prosthetics expert who had worked for the ICRC in the Gaza strip. His friend a 23- year-old Russian woman was raped with one witness telling the local media that four men ―stripped and raped her mercilessly although she was bleeding from her head.‖ The main suspect in the case is ruling party politician and well-known thug Sampath Vidanapathirana a close friend of the Rajapakse family. Refuge for criminals and rapscallions Clearly the ruling regime has become a refuge for criminals and rapscallions as the Sri Lankan government fails to maintain law and order and encourages lawlessness and criminal behaviour instead.