Aphids and Their Control on Orchids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aphis Fabae Scop.) to Field Beans ( Vicia Faba L.

ANALYSIS OF THE DAMAGE CAUSED BY THE BLACK BEAN APHID ( APHIS FABAE SCOP.) TO FIELD BEANS ( VICIA FABA L.) BY JESUS ANTONIO SALAZAR, ING. AGR. ( VENEZUELA ) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LONDON OCTOBER 1976 IMPERIAL COLLEGE FIELD STATION, SILWOOD PARK, SUNNINGHILL, ASCOT, BERKSHIRE. 2 ABSTRACT The concept of the economic threshold and its importance in pest management programmes is analysed in Chapter I. The significance of plant responses or compensation in the insect-injury-yield relationship is also discussed. The amount of damage in terms of yield loss that results from aphid attack, is analysed by comparing the different components of yield in infested and uninfested plants. In the former, plants were infested at different stages of plant development. The results showed that seed weights, pod numbers and seed numbers in plants infested before the flowering period were significantly less than in plants infested during or after the period of flower setting. The growth pattern and growth analysis in infested and uninfested plants have shown that the rate of leaf production and dry matter production were also more affected when the infestations occurred at early stages of plant development. When field beans were infested during the flowering period and afterwards, the aphid feeding did not affect the rate of leaf and dry matter production. There is some evidence that the rate of leaf area production may increase following moderate aphid attack during this period. The relationship between timing of aphid migration from the wintering host and the stage of plant development are shown to be of considerable significance in determining the economic threshold for A. -

(Pentatomidae) DISSERTATION Presented

Genome Evolution During Development of Symbiosis in Extracellular Mutualists of Stink Bugs (Pentatomidae) DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alejandro Otero-Bravo Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee: Zakee L. Sabree, Advisor Rachelle Adams Norman Johnson Laura Kubatko Copyrighted by Alejandro Otero-Bravo 2020 Abstract Nutritional symbioses between bacteria and insects are prevalent, diverse, and have allowed insects to expand their feeding strategies and niches. It has been well characterized that long-term insect-bacterial mutualisms cause genome reduction resulting in extremely small genomes, some even approaching sizes more similar to organelles than bacteria. While several symbioses have been described, each provides a limited view of a single or few stages of the process of reduction and the minority of these are of extracellular symbionts. This dissertation aims to address the knowledge gap in the genome evolution of extracellular insect symbionts using the stink bug – Pantoea system. Specifically, how do these symbionts genomes evolve and differ from their free- living or intracellular counterparts? In the introduction, we review the literature on extracellular symbionts of stink bugs and explore the characteristics of this system that make it valuable for the study of symbiosis. We find that stink bug symbiont genomes are very valuable for the study of genome evolution due not only to their biphasic lifestyle, but also to the degree of coevolution with their hosts. i In Chapter 1 we investigate one of the traits associated with genome reduction, high mutation rates, for Candidatus ‘Pantoea carbekii’ the symbiont of the economically important pest insect Halyomorpha halys, the brown marmorated stink bug, and evaluate its potential for elucidating host distribution, an analysis which has been successfully used with other intracellular symbionts. -

Correlation of Stylet Activities by the Glassy-Winged Sharpshooter, Homalodisca Coagulata (Say), with Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG) Waveforms

ARTICLE IN PRESS Journal of Insect Physiology 52 (2006) 327–337 www.elsevier.com/locate/jinsphys Correlation of stylet activities by the glassy-winged sharpshooter, Homalodisca coagulata (Say), with electrical penetration graph (EPG) waveforms P. Houston Joosta, Elaine A. Backusb,Ã, David Morganc, Fengming Yand aDepartment of Entomology, University of Riverside, Riverside, CA 92521, USA bUSDA-ARS Crop Diseases, Pests and Genetics Research Unit, San Joaquin Valley Agricultural Sciences Center, 9611 South Riverbend Ave, Parlier, CA 93648, USA cCalifornia Department of Food and Agriculture, Mt. Rubidoux Field Station, 4500 Glenwood Dr., Bldg. E, Riverside, CA 92501, USA dCollege of Life Sciences, Peking Univerisity, Beijing, China Received 5 May 2005; received in revised form 29 November 2005; accepted 29 November 2005 Abstract Glassy-winged sharpshooter, Homalodisca coagulata (Say), is an efficient vector of Xylella fastidiosa (Xf), the causal bacterium of Pierce’s disease, and leaf scorch in almond and oleander. Acquisition and inoculation of Xf occur sometime during the process of stylet penetration into the plant. That process is most rigorously studied via electrical penetration graph (EPG) monitoring of insect feeding. This study provides part of the crucial biological meanings that define the waveforms of each new insect species recorded by EPG. By synchronizing AC EPG waveforms with high-magnification video of H. coagulata stylet penetration in artifical diet, we correlated stylet activities with three previously described EPG pathway waveforms, A1, B1 and B2, as well as one ingestion waveform, C. Waveform A1 occured at the beginning of stylet penetration. This waveform was correlated with salivary sheath trunk formation, repetitive stylet movements involving retraction of both maxillary stylets and one mandibular stylet, extension of the stylet fascicle, and the fluttering-like movements of the maxillary stylet tips. -

Twenty-Five Pests You Don't Want in Your Garden

Twenty-five Pests You Don’t Want in Your Garden Prepared by the PA IPM Program J. Kenneth Long, Jr. PA IPM Program Assistant (717) 772-5227 [email protected] Pest Pest Sheet Aphid 1 Asparagus Beetle 2 Bean Leaf Beetle 3 Cabbage Looper 4 Cabbage Maggot 5 Colorado Potato Beetle 6 Corn Earworm (Tomato Fruitworm) 7 Cutworm 8 Diamondback Moth 9 European Corn Borer 10 Flea Beetle 11 Imported Cabbageworm 12 Japanese Beetle 13 Mexican Bean Beetle 14 Northern Corn Rootworm 15 Potato Leafhopper 16 Slug 17 Spotted Cucumber Beetle (Southern Corn Rootworm) 18 Squash Bug 19 Squash Vine Borer 20 Stink Bug 21 Striped Cucumber Beetle 22 Tarnished Plant Bug 23 Tomato Hornworm 24 Wireworm 25 PA IPM Program Pest Sheet 1 Aphids Many species (Homoptera: Aphididae) (Origin: Native) Insect Description: 1 Adults: About /8” long; soft-bodied; light to dark green; may be winged or wingless. Cornicles, paired tubular structures on abdomen, are helpful in identification. Nymph: Daughters are born alive contain- ing partly formed daughters inside their bodies. (See life history below). Soybean Aphids Eggs: Laid in protected places only near the end of the growing season. Primary Host: Many vegetable crops. Life History: Females lay eggs near the end Damage: Adults and immatures suck sap from of the growing season in protected places on plants, reducing vigor and growth of plant. host plants. In spring, plump “stem Produce “honeydew” (sticky liquid) on which a mothers” emerge from these eggs, and give black fungus can grow. live birth to daughters, and theygive birth Management: Hide under leaves. -

PRA Cerataphis Lataniae

CSL Pest Risk Analysis for Cerataphis lataniae CSL copyright, 2005 Pest Risk Analysis for Cerataphis lataniae Boisduval STAGE 1: PRA INITIATION 1. What is the name of the pest? Cerataphis lataniae (Boisduval) Hemiptera Aphididae the Latania aphid Synonyms: Ceratovacuna palmae (Baehr) Aphis palmae (Baehr) Boisduvalia lataniae (Boisduval) Note: In the past C. lataniae has been confused with both C. brasiliensis and C. orchidearum (Howard, 2001). As a result it is not always clear which of the older records for host plants and distribution refer to which species. BAYER CODES: CEATLA 2. What is the reason for the PRA? This PRA was initiated following a second interception of this species. Cerataphis lataniae was first intercepted in the UK in 1999 on a consignment of Archontophoenix alexandra and Brahea drandegai, from South Africa. Since then it has been intercepted twice more; on 30/05/02 on Cocos spp. and then again on 13/06/02 on Cocos nucifera. Both the findings in 2002 were at the same botanic garden and there is some suggestion the Coco plants were supplied by the nursery where the first interception was made in 1999. 3. What is the PRA area? As C. lataniae is present within the EU (Germany, Italy, Spain) (See point 11.) this PRA only considers the UK. STAGE 2: PEST RISK ASSESSMENT 4. Does the pest occur in the PRA area or does it arrive regularly as a natural migrant? No. Although Cerataphis lataniae is included on the British checklist this is likely to be an invalid record as there is no evidence to suggest it is established in the UK (R. -

Melon Aphid Or Cotton Aphid, Aphis Gossypii Glover (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphididae)1 John L

EENY-173 Melon Aphid or Cotton Aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphididae)1 John L. Capinera2 Distribution generation can be completed parthenogenetically in about seven days. Melon aphid occurs in tropical and temperate regions throughout the world except northernmost areas. In the In the south, and at least as far north as Arkansas, sexual United States, it is regularly a pest in the southeast and forms are not important. Females continue to produce southwest, but is occasionally damaging everywhere. Be- offspring without mating so long as weather allows feeding cause melon aphid sometimes overwinters in greenhouses, and growth. Unlike many aphid species, melon aphid is and may be introduced into the field with transplants in the not adversely affected by hot weather. Melon aphid can spring, it has potential to be damaging almost anywhere. complete its development and reproduce in as little as a week, so numerous generations are possible under suitable Life Cycle and Description environmental conditions. The life cycle differs greatly between north and south. In the north, female nymphs hatch from eggs in the spring on Egg the primary hosts. They may feed, mature, and reproduce When first deposited, the eggs are yellow, but they soon parthenogenetically (viviparously) on this host all summer, become shiny black in color. As noted previously, the eggs or they may produce winged females that disperse to normally are deposited on catalpa and rose of sharon. secondary hosts and form new colonies. The dispersants typically select new growth to feed upon, and may produce Nymph both winged (alate) and wingless (apterous) female The nymphs vary in color from tan to gray or green, and offspring. -

Influence of Plant Parameters on Occurrence and Abundance Of

HORTICULTURAL ENTOMOLOGY Influence of Plant Parameters on Occurrence and Abundance of Arthropods in Residential Turfgrass 1 S. V. JOSEPH AND S. K. BRAMAN Department of Entomology, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, University of Georgia, 1109 Experiment Street, GrifÞn, GA 30223-1797 J. Econ. Entomol. 102(3): 1116Ð1122 (2009) ABSTRACT The effect of taxa [common Bermuda grass, Cynodon dactylon (L.); centipedegrass, Eremochloa ophiuroides Munro Hack; St. Augustinegrass, Stenotaphrum secundatum [Walt.] Kuntze; and zoysiagrass, Zoysia spp.], density, height, and weed density on abundance of natural enemies, and their potential prey were evaluated in residential turf. Total predatory Heteroptera were most abundant in St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass and included Anthocoridae, Lasiochilidae, Geocoridae, and Miridae. Anthocoridae and Lasiochilidae were most common in St. Augustinegrass, and their abundance correlated positively with species of Blissidae and Delphacidae. Chinch bugs were present in all turf taxa, but were 23Ð47 times more abundant in St. Augustinegrass. Anthocorids/lasiochilids were more numerous on taller grasses, as were Blissidae, Delphacidae, Cicadellidae, and Cercopidae. Geocoridae and Miridae were most common in zoysiagrass and were collected in higher numbers with increasing weed density. However, no predatory Heteroptera were affected by grass density. Other beneÞcial insects such as staphylinids and parasitic Hymenoptera were captured most often in St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass. These differences in abundance could be in response to primary or alternate prey, or reßect the inßuence of turf microenvironmental characteristics. In this study, SimpsonÕs diversity index for predatory Heteroptera showed the greatest diversity and evenness in centipedegrass, whereas the herbivores and detritivores were most diverse in St. Augustinegrass lawns. These results demonstrate the complex role of plant taxa in structuring arthropod communities in turf. -

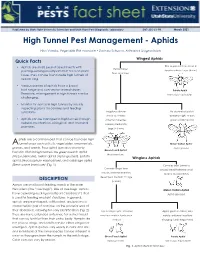

High Tunnel Pest Management - Aphids

Published by Utah State University Extension and Utah Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory ENT-225-21-PR March 2021 High Tunnel Pest Management - Aphids Nick Volesky, Vegetable IPM Associate • Zachary Schumm, Arthropod Diagnostician Winged Aphids Quick Facts • Aphids are small, pear-shaped insects with Thorax green; no abdominal Thorax darker piercing-sucking mouthparts that feed on plant dorsal markings; large (4 mm) than abdomen tissue. They can be found inside high tunnels all season long. • Various species of aphids have a broad host range and can vector several viruses. Potato Aphid Therefore, management in high tunnels can be Macrosipu euphorbiae challenging. • Monitor for aphids in high tunnels by visually inspecting plants for colonies and feeding symptoms. Irregular patch on No abdominal patch; dorsal abdomen; abdomen light to dark • Aphids can be managed in high tunnels through antennal tubercles green; small (<2 mm) cultural, mechanical, biological, and chemical swollen; medium to practices. large (> 3 mm) phids are a common pest that can be found on high Atunnel crops such as fruits, vegetables, ornamentals, Melon Cotton Aphid grasses, and weeds. Four aphid species commonly Aphis gossypii Green Peach Aphid found in Utah in high tunnels are green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Myzus persicae), melon aphid (Aphis gossypii), potato Wingless Aphids aphid (Macrosiphum euphorbiae), and cabbage aphid (Brevicoryne brassicae) (Fig. 1). Cornicles short (same as Cornicles longer than cauda); head flattened; small cauda; antennal insertions (2 mm), rounded body DESCRIPTION developed; medium to large (> 3mm) Aphids are small plant feeding insects in the order Hemiptera (the “true bugs”). Like all true bugs, aphids Melon Cotton Aphid have a piercing-sucking mouthpart (“proboscis”) that Aphis gossypii is used for feeding on plant structures. -

Alfalfa Aphid and Leafhopper Management for the Low Deserts

ALFALFA APHID AND LEAFHOPPER MANAGEMENT FOR THE LOW DESERTS Eric T. Natwick U.C. Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor, Imperial County, California APHIDS Spotted Alfalfa ~ The spotted alfalfa aphid (Therioaphis maculata) was introduced into New Mexico in 1953 and by 1954 had spread westward into California. This aphid is small pale yellow or grayish in color with 4 to 6 rows of black spots bearing small spines on its back. The adults mayor may not have wings. Spotted alfalfa aphid is smaller than blue alfalfa aphid or pea aphid arid will readily drop from plants when disturbed. The aphids are common on the underside of leaves where colonies start on the lower part of the plants, but also infest stems and leaves ~s colonies expand. These aphids produce great Quantities of honeydew. Severe infestations can develop on non-resistant varieties of alfalfa and reduce yield, stunt growth and even kill plants. Feed Quality and palatability are also reduced by sooty molds which grow on the honeydew excrement. In most desert growing areas introduction of resistant varieties (e.g., CUF101) along with the activity of predacious bugs, lady beetles, lacewings, syrphid fly larvae and introduced parasites has reduced this aphid to the status of a minor pest. If susceptible varieties are planted and beneficial insect populations are disrupted, then severe infestations can occur from late July through September. Because spotted alfalfa aphid has developed resistance to organophosphorus compounds, the best way to avoid aphid problems is the planting of a resistant variety. In fields where a susceptible variety is planted the field should be checked 2 to 3 times per week during July through September. -

A Contribution to the Aphid Fauna of Greece

Bulletin of Insectology 60 (1): 31-38, 2007 ISSN 1721-8861 A contribution to the aphid fauna of Greece 1,5 2 1,6 3 John A. TSITSIPIS , Nikos I. KATIS , John T. MARGARITOPOULOS , Dionyssios P. LYKOURESSIS , 4 1,7 1 3 Apostolos D. AVGELIS , Ioanna GARGALIANOU , Kostas D. ZARPAS , Dionyssios Ch. PERDIKIS , 2 Aristides PAPAPANAYOTOU 1Laboratory of Entomology and Agricultural Zoology, Department of Agriculture Crop Production and Rural Environment, University of Thessaly, Nea Ionia, Magnesia, Greece 2Laboratory of Plant Pathology, Department of Agriculture, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece 3Laboratory of Agricultural Zoology and Entomology, Agricultural University of Athens, Greece 4Plant Virology Laboratory, Plant Protection Institute of Heraklion, National Agricultural Research Foundation (N.AG.RE.F.), Heraklion, Crete, Greece 5Present address: Amfikleia, Fthiotida, Greece 6Present address: Institute of Technology and Management of Agricultural Ecosystems, Center for Research and Technology, Technology Park of Thessaly, Volos, Magnesia, Greece 7Present address: Department of Biology-Biotechnology, University of Thessaly, Larissa, Greece Abstract In the present study a list of the aphid species recorded in Greece is provided. The list includes records before 1992, which have been published in previous papers, as well as data from an almost ten-year survey using Rothamsted suction traps and Moericke traps. The recorded aphidofauna consisted of 301 species. The family Aphididae is represented by 13 subfamilies and 120 genera (300 species), while only one genus (1 species) belongs to Phylloxeridae. The aphid fauna is dominated by the subfamily Aphidi- nae (57.1 and 68.4 % of the total number of genera and species, respectively), especially the tribe Macrosiphini, and to a lesser extent the subfamily Eriosomatinae (12.6 and 8.3 % of the total number of genera and species, respectively). -

The Semiaquatic Hemiptera of Minnesota (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) Donald V

The Semiaquatic Hemiptera of Minnesota (Hemiptera: Heteroptera) Donald V. Bennett Edwin F. Cook Technical Bulletin 332-1981 Agricultural Experiment Station University of Minnesota St. Paul, Minnesota 55108 CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ...................................3 Key to Adults of Nearctic Families of Semiaquatic Hemiptera ................... 6 Family Saldidae-Shore Bugs ............... 7 Family Mesoveliidae-Water Treaders .......18 Family Hebridae-Velvet Water Bugs .......20 Family Hydrometridae-Marsh Treaders, Water Measurers ...22 Family Veliidae-Small Water striders, Rime bugs ................24 Family Gerridae-Water striders, Pond skaters, Wherry men .....29 Family Ochteridae-Velvety Shore Bugs ....35 Family Gelastocoridae-Toad Bugs ..........36 Literature Cited ..............................37 Figures ......................................44 Maps .........................................55 Index to Scientific Names ....................59 Acknowledgement Sincere appreciation is expressed to the following individuals: R. T. Schuh, for being extremely helpful in reviewing the section on Saldidae, lending specimens, and allowing use of his illustrations of Saldidae; C. L. Smith for reading the section on Veliidae, checking identifications, and advising on problems in the taxon omy ofthe Veliidae; D. M. Calabrese, for reviewing the section on the Gerridae and making helpful sugges tions; J. T. Polhemus, for advising on taxonomic prob lems and checking identifications for several families; C. W. Schaefer, for providing advice and editorial com ment; Y. A. Popov, for sending a copy ofhis book on the Nepomorpha; and M. C. Parsons, for supplying its English translation. The University of Minnesota, including the Agricultural Experi ment Station, is committed to the policy that all persons shall have equal access to its programs, facilities, and employment without regard to race, creed, color, sex, national origin, or handicap. The information given in this publication is for educational purposes only. -

Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal BioRisk 4(1): 435–474 (2010) Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae). Chapter 9.2 435 doi: 10.3897/biorisk.4.57 RESEARCH ARTICLE BioRisk www.pensoftonline.net/biorisk Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae) Chapter 9.2 Armelle Cœur d’acier1, Nicolas Pérez Hidalgo2, Olivera Petrović-Obradović3 1 INRA, UMR CBGP (INRA / IRD / Cirad / Montpellier SupAgro), Campus International de Baillarguet, CS 30016, F-34988 Montferrier-sur-Lez, France 2 Universidad de León, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas y Ambientales, Universidad de León, 24071 – León, Spain 3 University of Belgrade, Faculty of Agriculture, Nemanjina 6, SER-11000, Belgrade, Serbia Corresponding authors: Armelle Cœur d’acier ([email protected]), Nicolas Pérez Hidalgo (nperh@unile- on.es), Olivera Petrović-Obradović ([email protected]) Academic editor: David Roy | Received 1 March 2010 | Accepted 24 May 2010 | Published 6 July 2010 Citation: Cœur d’acier A (2010) Aphids (Hemiptera, Aphididae). Chapter 9.2. In: Roques A et al. (Eds) Alien terrestrial arthropods of Europe. BioRisk 4(1): 435–474. doi: 10.3897/biorisk.4.57 Abstract Our study aimed at providing a comprehensive list of Aphididae alien to Europe. A total of 98 species originating from other continents have established so far in Europe, to which we add 4 cosmopolitan spe- cies of uncertain origin (cryptogenic). Th e 102 alien species of Aphididae established in Europe belong to 12 diff erent subfamilies, fi ve of them contributing by more than 5 species to the alien fauna. Most alien aphids originate from temperate regions of the world. Th ere was no signifi cant variation in the geographic origin of the alien aphids over time.