Orthodontically Assisted Restorative Dentistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two-Year Clinical Evaluation of Nonvital Tooth Whitening and Resin Composite Restorations

Two-Year Clinical Evaluation of Nonvital Tooth Whitening and Resin Composite Restorations SIMONE DELIPERI, DDS* DAVID N. BARDWELL, DDS, MS† ABSTRACT Background: Adhesive systems, resin composites, and light curing systems underwent continuous improvement in the past decade. The number of patients asking for ultraconservative treatments is increasing; clinicians are starting to reevaluate the dogma of traditional restorative dentistry and look for alternative methods to build up severely destroyed teeth. Purpose: The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of nonvital tooth whitening and the clinical performance of direct composite restorations used to reconstruct extensive restora- tions on endodontically bleached teeth. Materials and Methods: Twenty-one patients 18 years or older were included in this clinical trial, and 26 endodontically treated and bleached maxillary and mandibular teeth were restored using a microhybrid resin composite. Patients with severe internal (tetracycline stains) and external dis- coloration (fluorosis), smokers, and pregnant and nursing women were excluded from the study. Only patients with A3 or darker shades were included. Teeth having endodontic access opening only to be restored were excluded; conversely, teeth having a combination of endodontic access and Class III/IV cavities were included in the study. A Vita shade guide (Vita Zahnfabrik, Bad Säckingen, Germany) arranged by value order was used to record the shade for each patient. Temporary or existing restorations were removed, along with a 1 mm gutta-percha below the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), and a resin-modified glass ionomer barrier was placed at the CEJ. Bleaching treatment was performed using a combination of in-office (OpalescenceXtra, Ultradent Products, South Jordan, UT, USA) and at-home (Opalescence 10% PF, Ultradent Prod- ucts) applications. -

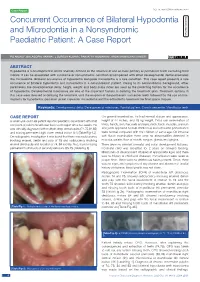

Concurrent Occurrence of Bilateral Hypodontia and Microdontia in a Nonsyndromic Paediatric Patient: a Case Report

Case Report DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2020/43540.14083 Concurrent Occurrence of Bilateral Hypodontia Dentistry Section and Microdontia in a Nonsyndromic Paediatric Patient: A Case Report PG ANJALI1, BALAGOpaL VARMA2, J SURESH KUMAR3, paRVATHY KUMARAN4, ARUN MAMACHAN XAVIER5 ABSTRACT Hypodontia is a developmental dental anomaly defined as the absence of one or more primary or permanent teeth excluding third molars. It can be associated with syndrome or nonsyndromic condition accompanied with other developmental dental anomalies like microdontia. Bilateral occurrence of hypodontia alongside microdontia is a rare condition. This case report presents a rare occurrence of bilateral hypodontia and microdontia in a nonsyndromic patient. Owing to its nonsyndromic background, other parameters like developmental delay, height, weight and body mass index are used as the predicting factors for the occurrence of hypodontia. Developmental milestones are one of the important factors in deriving the treatment plan. Treatment options in this case were directed at delaying the treatment until the eruption of the permanent successor teeth followed by the use of mini- implants for hypodontia, porcelain jacket crown for microdontia and the orthodontic treatment for final space closure. Keywords: Developmental delay, Developmental milestones, Familial pattern, Growth percentile, Mandibular teeth CASE REPORT On general examination, he had normal stature and appearance, A seven-year-old male patient reported paediatric department with chief height of 44 inches, and 18 kg weight. Extra oral examination of complaint of pain in the left lower back tooth region since two weeks. He limbs, hands, skin, hair, nails and eyes, neck, back, muscles, cranium was clinically diagnosed with multiple deep dental caries (74,75,84,85) and joints appeared normal. -

The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry

The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry COPYRIGHT © 2002 BY QUINTESSENCE PUBLISHING CO, INC. PRINTING OF THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED TO PERSONAL USE ONLY.NO PART OF THIS ARTICLE MAY BE REPRO- DUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER. 451 DUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER. WRITTEN PERMISSION FROM WITHOUT TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM DUCED OR THI OF PART PERSONAL USE ONLY.NO INC.TO PUBLISHING CO, COPYRIGHT © 2002 BY QUINTESSENCE THIS DOCUMENT IS RESTRICTED PRINTING OF Immediate Loading of Osseotite Implants: A Case Report and Histologic Analysis After 4 Months of Occlusal Loading Tiziano Testori, MD, DDS*/Serge Szmukler-Moncler, DDS**/ The original Brånemark protocol rec- Luca Francetti, MD, DDS***/Massimo Del Fabbro, BSc, PhD****/ ommended long stress-free healing Antonio Scarano, DDS*****/Adriano Piattelli, MD, DDS******/ periods to achieve the osseointe- Roberto L. Weinstein, MD, DDS******* gration of dental implants.1–4 However, a growing number of A growing number of clinical reports show that early and immediate loading of 5–11 endosseous implants may lead to predictable osseointegration; however, these experimental and clinical stud- studies provide mostly short- to mid-term results based only on clinical mobility and ies12–19 are now showing that early radiographic observation. Other methods are needed to detect the possible pres- and immediate loading may lead to ence of a thin fibrous interposition of tissue that could increase in the course of time predictable osseointegration. A and lead to clinical mobility. A histologic evaluation was performed on two immedi- review of the experimental9 and clin- ately loaded Osseotite implants retrieved after 4 months of function from one ical19 literature discussing early load- patient. -

The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry

Celletti.qxd 3/14/08 3:41 PM Page 144 The International Journal of Periodontics & Restorative Dentistry Celletti.qxd 3/14/08 3:41 PM Page 145 145 Bone Contact Around Osseointegrated Implants: Histologic Analysis of a Dual–Acid-Etched Surface Implant in a Diabetic Patient Calogero Bugea, DDS* The clinical applicability and pre- Roberto Luongo, DDS** dictability of osseointegrated implants Donato Di Iorio, DDS* placed in healthy patients have been *** Roberto Cocchetto, MD, DDS studied extensively. Long-term suc- **** Renato Celletti, MD, DDS cess has been shown in both com- pletely and partially edentulous patients.1–6 Although replacement of teeth with dental implants has become The clinical applicability and predictability of osseointegrated implants in healthy an effective modality, the implants’ pre- patients have been studied extensively. Although successful treatment of patients dictability relies on successful osseoin- with medical conditions including diabetes, arthritis, and cardiovascular disease tegration during the healing period.7 has been described, insufficient information is available to determine the effects of diabetes on the process of osseointegration. An implant placed and intended Patient selection criteria are to support an overdenture in a 65-year-old diabetic woman was prosthetically important. The impact of systemic unfavorable and was retrieved after 2 months. It was then analyzed histologically. pathologies on implant-to-tissue inte- No symptoms of implant failure were detected, and histomorphometric evaluation gration is currently unclear. The liter- showed the bone-to-implant contact percentage to be 80%. Osseointegration can ature cites the inability of a patient to be obtained when implants with a dual–acid-etched surface are placed in properly undergo an elective surgical proce- selected diabetic patients. -

Job Description Template

NHS HIGHLAND 1 JOB DESCRIPTION 1. JOB IDENTIFICATION Job Title: Dental Nurse in Restorative Dentistry Locations: Inverness Dental Centre CfHS and Raigmore Hospital, Inverness Department: Restorative Dentistry Service Operational Unit/Corporate Department: Raigmore, Surgical Division Job Reference: SSSARAIGDENT13 No of Job Holders: 1 Last Update: August 2015 2 3 2. JOB PURPOSE To carry out Dental Nursing and administrative duties in support of the Restorative Dentistry Service delivered by the Consultant in Restorative Dentistry in NHS Highland and trainees allocated to this service. This post has specific duties and responsibilities related to the care of patients affected by head and neck cancer, dental implants and complex restorative treatment including endodontics, prosthodontics and periodontics. To work as part of a team of Dental Nurses, giving clinical & administrative assistance as required to Clinicians (Consultant and NES trainees). The post will include all duties normally expected of a Qualified Dental Nurse required to provide high quality patient care. To participate in all programmes arranged for the training of Dental Nurses in order to meet agreed quality standards, to maintain awareness of any changes in dentistry and to participate in continuing personal and professional development. To Participate in Audit and research programmes as required. Maintain a high standard of infection control. 3. DIMENSIONS Provision of routine and emergency dental care to a range of adults who are referred to secondary care NHS HIGHLAND Restorative Service in Raigmore. The consultant works multiple sites, including Raigmore Hospital, Inverness Dental Centre, Stornoway and Elgin. The post holder will be required to work flexibly across a variety of services including; Hospital, Public dental services, General Anaesthetic, Relative Analgesia and IV Sedation. -

General& Restorative Dentistry

General& Restorative Dentistry Fillings 1. Amalgam restorations ( for small, medium large restorations) 2. Direct composite restorations (for small – medium restorations) 3. Glass ionomer restorations (for small restorations) 4. CEREC all ceramic restorations ( for medium – large restorations) Amalgam restorations: Every dental material used to rebuild teeth has advantages and disadvantages. Dental amalgam or silver fillings have been around for over 150 years. Amalgam is composed of silver, tin, copper, mercury and zinc. Amalgam fillings are relatively inexpensive, durable and time-tested. Amalgam fillings are considered un-aesthetic because they blacken over time and can give teeth a grey appearance, and they do not strengthen the tooth. Some people worry about the potential for mercury in dental amalgam to leak out and cause a wide variety of ailments. At this stage such allegations are unsubstantiated in the wider community and the NHMRC still considers amalgam restorations as a safe material to use in the adult patient. Composite restorations: Composite fillings are composed of a tooth-coloured plastic mixture filled with glass (silicon dioxide). Introduced in the 1960s, dental composites were confined to the front teeth because they were not strong enough to withstand the pressure and wear generated by the back teeth. Since then, composites have been significantly improved and can be successfully placed in the back teeth as well. Composite fillings are the material of choice for repairing the front teeth. Aesthetics are the main advantage, since dentists can blend shades to create a colour nearly identical to that of the actual tooth. Composites bond to the tooth to support the remaining tooth structure, which helps to prevent breakage and insulate the tooth from excessive temperature changes. -

Fusobacteria Bacteremia Post Full Mouth Disinfection Therapy: a Case Report

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 14, Issue 7 Ver. VI (July. 2015), PP 77-81 www.iosrjournals.org Fusobacteria Bacteremia Post Full Mouth Disinfection Therapy: A Case Report Parth, Purwar1, Vaibhav Sheel1, Manisha Dixit1, Jaya Dixit1 1 Department of Periodontology, Faculty of Dental Sciences, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. Abstract: Oral bacteria under certain circumstances can enter the systemic circulation and can lead to adverse systemic effects. Fusobacteria species are numerically dominant species in dental plaque biofilms and are also associated with negative systemic outcomes. In the present case report, full mouth disinfection (FMD) was performed in a systemically healthy chronic periodontitis patient and the incidence of fusobateria species bacteremia in peripheral blood was evaluated before, during and after FMD. The results showed a significant increase in fusobacterium sp. bacteremia post FMD and the levels remained higher even after 30 minutes. In the light of the results it can be proposed that single visit FMD may result in transient bacteraemia. Keywords: Chronic Periodontitis, Non surgical periodontal therapy, Fusobacterium species, Full mouth disinfection Therapy I. Introduction After scaling and root planing (SRP), bacteremia has been analyzed predominately in aerobic and gram-positive bacteria. Fusobaterium is a potential periopathogen which upon migration to extra-oral sites may provide a significant and persistent gram negative challenge to the host and may enhance the risk of adverse cardiovascular and pregnancy complications [1].To the authors knowledge this is a seminal case report which gauges the occurrence and magnitude of fusobactrium sp. -

A Brief History of Osseointegration: a Review

IP Annals of Prosthodontics and Restorative Dentistry 2021;7(1):29–36 Content available at: https://www.ipinnovative.com/open-access-journals IP Annals of Prosthodontics and Restorative Dentistry Journal homepage: https://www.ipinnovative.com/journals/APRD Review Article A brief history of osseointegration: A review Myla Ramakrishna1,*, Sudheer Arunachalam1, Y Ramesh Babu1, Lalitha Srivalli2, L Srikanth1, Sudeepti Soni3 1Dept. of Prosthodontics, Crown and Bridge, Sree Sai Dental College & Research Institute, Srikakulam, Andhra Pradesh, India 2National Institute for Mentally Handicapped, NIEPID, Secunderbad, Telangana, India 3Dept. of Prosthodontic, Crown and Bridge, New Horizon Dental College and Research Institute, Bilaspur, Chhattisgarh, India ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Article history: Background: osseointegration of dental implants refers to direct structural and functional link between Received 11-01-2021 living bone and the surface of non-natural implants. It follows bonding up of an implant into jaw bone Accepted 22-02-2021 when bone cells fasten themselves directly onto the titanium surface.it is the most investigated area in Available online 26-02-2021 implantology in recent times. Evidence based data revels that osseointegrated implants are predictable and highly successful. This process is relatively complex and is influenced by various factors in formation of bone neighbouring implant surface. Keywords: Osseointegration © This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Implant License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and Bone reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. 1. Introduction 1.1. History Missing teeth and there various attempts to replace them has An investigational work was carried out in Sweden by presented a treatment challenge throughout human history. -

Section I the Patient BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38

BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38 Section I The Patient BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38 “I’m ready when you are.” 2 BLUK133-Jacobsen December 7, 2007 16:38 Chapter 1 The Patient – His Limitations and Expectations Section I The provision of high-quality restorative dentistry depends upon the dentist: Making an accurate diagnosis Devising a comprehensive and realistic treatment plan Executing the treatment plan to a high technical standard Providing subsequent continuing care There is a very strong tendency, particularly in the and here re-education is often necessary to bring him field of fixed prosthodontics, for the dentist to become down to the practical and feasible. over-interested in the technical execution of treat- It might be that the dentist has the skills and tech- ment. There is a vast range of materials and equip- nical facilities to perform advanced procedures, but ment to stimulate this interest and compete for his before he puts bur to tooth, he must stop and ask attention. It is perhaps inevitable that dentists can be- whether this is really what this patient needs and come obsessive about types of bur or root canal file, wants. If the answer is no, then to proceed is an act the pros and cons of various materials and the precise of pure selfishness that might also be regarded as techniques of restoration. negligent! This is not to decry such interest because a high Certainly the dentist may have certain treatment standard of technical execution is essential for the goals for all his patients – no pain or caries, healthy longevity of restorations. -

The Management of Developmentally Absent Maxillary Lateral Incisors–A

RESEARCH IN BRIEF • Orthodontists work in two distinct practice organisations: one with limited access to a restorative opinion and one with ready access to restorative opinions. • The type of practice environment influences the type of treatment offered. • Orthodontists working with limited or no access to restorative dentists evaluate the space for implants from the inter-crown distance. • Orthodontists who work regularly with restorative colleagues evaluate the distance between the roots of adjacent teeth from an intra-oral radiograph. • Orthodontists who work in isolation are recommended to evaluate the space for implants and hence the need for orthodontics from intra-oral radiographs. • There is a need to promote clearer guidelines and protocols for practitioners involved in the management of hypodontia. The management of developmentally absent maxillary lateral incisors – a survey of orthodontists in the UK J. D. Louw,1 B. J. Smith,2 F. McDonald3 and R. M. Palmer4 Objective To investigate the orthodontic management of patients restorative dentistry advice. The influence of these factors was greater with developmentally absent maxillary lateral incisors. for the treatment options of space closure or replacement via resin Materials and methods A questionnaire was mailed to all orthodon retained bridges but less so for implant treatment. This reinforces the tists on the specialist list held by the British Orthodontic Society. need for multidisciplinary involvement. Results The questionnaires (57.3% response) were analysed in two groups: Group 1 consisted of orthodontists who worked only in an INTRODUCTION orthodontic practice environment; Group 2 consisted of orthodontists Approximately 2% of the UK population have developmentally who worked full-time or part-time in an environment where there were absent maxillary lateral incisors.1 The prevalence is higher restorative dentists available for advice. -

Periodontics Restorative Dentistry

10Successfullyth INTERNATIONAL Integrating QUINTESSENCE the Best of Traditional SYMPOSIUM & Digital on Dentistry PERIODONTICS Up to RESTORATIVE & 28 DENTISTRY CPD Hours New Frontiers of Aesthetic Excellence Successfully Integrating the Best of Traditional & Digital Dentistry including an extra Pre-Symposium in-depth day on 11 October 2018 HILTON HOTEL, SYDNEY AUSTRALIA OCTOBER 11-14 2018 Proudly sponsored by Henry Schein Halas guarantees the courses advertised are fully compliant with the current Dental Board of Australia Guidelines on Continuing Professional Development. New Frontiers of Aesthetic Excellence Successfully New Integrating Frontiers the of Best Aesthetic of Traditional Exce & llenceDigital Dentistry Meet the Presenters Successfully Integrating the Best of Traditional & Digital Dentistry Dr Deborah Bomfim Scientific Chairman BDS, MSc, MJDF, FDSRCS Professor Laurence London, UK Walsh Deborah is a Consultant and Clinical Lecturer in Restorative Dentistry BDSc, PhD, DDSc, GCEd, FRACDS, at UCLH Eastman Dental Hospital FFOP(RCPA), AO in the units of Periodontology and Brisbane, Australia Prosthodontics. She completed her dental training at King's College London Laurence completed his undergraduate Dental Institute, and worked at four major London teaching training at University of Queensland in 1983 and his PhD in hospitals, before undertaking her specialist training at the 1987, then undertook postdoctoral studies at the University Eastman Dental Institute in the field of Restorative Dentistry, of Pennsylvania and at Stanford University. He is a board- covering Prosthodontics, Periodontology, Endodontics and registered specialist in special needs dentistry, and immediate Implant Dentistry. Deborah works in leading multi-specialist past president of the ANZ Academy of Special Needs Dentistry. practices in London, providing complex prosthodontic, Laurence holds a personal chair in dental science at the periodontology and implant dentistry. -

Gracis S. a Simplified Method to Develop An

CLINICAL RESEARCH A simplified method to develop an interdisciplinary treatment plan: an esthetically and functionally driven approach in three steps Stefano Gracis, DMD, MSD Private Practice, Milan, Italy Correspondence to: Dr Stefano Gracis Via Brera 28/a, 20121 Milan, Italy; Tel: +39 02 72094471; Email: [email protected] 76 | The International Journal of Esthetic Dentistry | Volume 16 | Number 1 | Spring 2021 GRACIS Abstract typically required. This article provides a practical step- by-step approach to planning comprehensive interdis- Many clinicians are unsure of how to develop a com- ciplinary treatment focused primarily on the teeth as prehensive plan of treatment for patients who present they relate to each other and to the structures that with multiple problems and pathologies. In order to surround them. The approach is based on the answers efficiently plan appropriate treatment for such com- to six questions that are grouped into three steps: 1) plex patient cases, the clinician needs to either have or evaluation of the teeth relative to the face and lips; develop the necessary knowledge of evidence-based 2) assessment of anterior tooth dimensions; and 3) information on the predictability of available clinical analysis of the anteroposterior and maxillomandibular procedures. The clinician also needs to understand relationships. The information obtained must then be the correct sequence in which such treatment is ap- related to the patient’s skeletal framework, periodontal plied, and perfect the skills required for carrying out status, caries susceptibility, and biomechanical risk as- that treatment. Since most clinicians have not ac- sessment in order to formulate a clear and complete quired all the knowledge and skills necessary for this plan of treatment.