An Explanation of the Citizenship Policies of Estonia and Lithuania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minorities and Majorities in Estonia: Problems of Integration at the Threshold of the Eu

MINORITIES AND MAJORITIES IN ESTONIA: PROBLEMS OF INTEGRATION AT THE THRESHOLD OF THE EU FLENSBURG, GERMANY AND AABENRAA DENMARK 22 to 25 MAY 1998 ECMI Report #2 March 1999 Contents Preface 3 The Map of Estonia 4 Ethnic Composition of the Estonian Population as of 1 January 1998 4 Note on Terminology 5 Background 6 The Introduction of the Seminar 10 The Estonian government's integration strategy 11 The role of the educational system 16 The role of the media 19 Politics of integration 22 International standards and decision-making on the EU 28 Final Remarks by the General Rapporteur 32 Appendix 36 List of Participants 37 The Integration of Non-Estonians into Estonian Society 39 Table 1. Ethnic Composition of the Estonian Population 43 Table 2. Estonian Population by Ethnic Origin and Ethnic Language as Mother Tongue and Second Language (according to 1989 census) 44 Table 3. The Education of Teachers of Estonian Language Working in Russian Language Schools of Estonia 47 Table 4 (A;B). Teaching in the Estonian Language of Other Subjects at Russian Language Schools in 1996/97 48 Table 5. Language Used at Home of the First Grade Pupils of the Estonian Language Schools (school year of 1996/97) 51 Table 6. Number of Persons Passing the Language Proficiency Examination Required for Employment, as of 01 August 1997 52 Table 7. Number of Persons Taking the Estonian Language Examination for Citizenship Applicants under the New Citizenship Law (enacted 01 April 1995) as of 01 April 1997 53 2 Preface In 1997, ECMI initiated several series of regional seminars dealing with areas where inter-ethnic tension was a matter of international concern or where ethnopolitical conflicts had broken out. -

Download Download

Ajalooline Ajakiri, 2016, 3/4 (157/158), 477–511 Historical consciousness, personal life experiences and the orientation of Estonian foreign policy toward the West, 1988–1991 Kaarel Piirimäe and Pertti Grönholm ABSTRACT The years 1988 to 1991 were a critical juncture in the history of Estonia. Crucial steps were taken during this time to assure that Estonian foreign policy would not be directed toward the East but primarily toward the integration with the West. In times of uncertainty and institutional flux, strong individuals with ideational power matter the most. This article examines the influence of For- eign Minister Lennart Meri’s and Prime Minister Edgar Savisaar’s experienc- es and historical consciousness on their visions of Estonia’s future position in international affairs. Life stories help understand differences in their horizons of expectation, and their choices in conducting Estonian diplomacy. Keywords: historical imagination, critical junctures, foreign policy analysis, So- viet Union, Baltic states, Lennart Meri Much has been written about the Baltic states’ success in breaking away from Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and their decisive “return to the West”1 via radical economic, social and politi- Research for this article was supported by the “Reimagining Futures in the European North at the End of the Cold War” project which was financed by the Academy of Finland. Funding was also obtained from the “Estonia, the Baltic states and the Collapse of the Soviet Union: New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War” project, financed by the Estonian Research Council, and the “Myths, Cultural Tools and Functions – Historical Narratives in Constructing and Consolidating National Identity in 20th and 21st Century Estonia” project, which was financed by the Turku Institute for Advanced Studies (TIAS, University of Turku). -

Improving Healthcare Quality in Europe

Cover_WHO_nr52.qxp_Mise en page 1 20/08/2019 16:31 Page 1 51 THE ROLE OF PUBLIC HEALTH ORGANIZATIONS IN ADDRESSING PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEMS IN EUROPE PUBLIC HEALTH IN ADDRESSING ORGANIZATIONS PUBLIC HEALTH THE ROLE OF Quality improvement initiatives take many forms, from the creation of standards for health Improving healthcare 53 professionals, health technologies and health facilities, to audit and feedback, and from fostering a patient safety culture to public reporting and paying for quality. For policy- makers who struggle to decide which initiatives to prioritise for investment, understanding quality in Europe Series the potential of different quality strategies in their unique settings is key. This volume, developed by the Observatory together with OECD, provides an overall conceptual Health Policy Health Policy framework for understanding and applying strategies aimed at improving quality of care. Characteristics, effectiveness and Crucially, it summarizes available evidence on different quality strategies and provides implementation of different strategies recommendations for their implementation. This book is intended to help policy-makers to understand concepts of quality and to support them to evaluate single strategies and combinations of strategies. Edited by Quality of care is a political priority and an important contributor to population health. This Reinhard Busse book acknowledges that "quality of care" is a broadly defined concept, and that it is often Niek Klazinga unclear how quality improvement strategies fit within a health system, and what their particular contribution can be. This volume elucidates the concepts behind multiple elements Dimitra Panteli of quality in healthcare policy (including definitions of quality, its dimensions, related activities, Wilm Quentin and targets), quality measurement and governance and situates it all in the wider context of health systems research. -

Identity and Integration of Russian Speakers in the Baltic States: a Framework for Analysis

This is an author’s final draft. The article has been published by Ethnopolitics. (2015) 14:1, pp.72-93: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17449057.2014.933051#.U8EwofldWSo Identity and Integration of Russian Speakers in the Baltic States: A Framework for Analysis Dr Ammon Cheskin, Central and East European Studies, University of Glasgow [email protected] Abstract: Following a review of current scholarship on identity and integration patterns of Russian speakers in the Baltic states, this article proposes an analytical framework to help understand current trends. Rogers Brubaker’s widely-employed triadic nexus is expanded to demonstrate why a form of Russian-speaking identity has been emerging, but has failed to become fully consolidated, and why significant integration has occurred structurally but not identificationally. By enumerating the subfields of political, economic, and cultural ‘stances’ and ‘representations’ the model helps to understand the complicated integration processes of minority groups that possess complex relationships with ‘external homelands’, ‘nationalizing states’ and ‘international organizations’. Ultimately, it is argued that socio-economic factors largely reduce the capacity for a consolidated identity; political factors have a moderate tendency to reduce this capacity; while cultural factors generally increase the potential for a consolidated group identity. This article proceeds by reviewing the scholarly literature from 1992-2014 relating to Russians/Russian speakers in the Baltic states. -

Rethinking European Union Foreign Policy Prelims 7/6/04 9:46 Am Page Ii

prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page i rethinking european union foreign policy prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page ii EUROPE IN CHANGE T C and E K already published The formation of Croatian national identity A centuries old dream . Committee governance in the European Union ₍₎ Theory and reform in the European Union, 2nd edition . , . , German policy-making and eastern enlargement of the EU during the Kohl era Managing the agenda . The European Union and the Cyprus conflict Modern conflict, postmodern union The time of European governance An introduction to post-Communist Bulgaria Political, economic and social transformation The new Germany and migration in Europe Turkey: facing a new millennium Coping with intertwined conflicts The road to the European Union, volume 2 Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania () The road to the European Union, volume 1 The Czech and Slovak Republics () Europe and civil society Movement coalitions and European governance Two tiers or two speeds? The European security order and the enlargement of the European Union and NATO () Recasting the European order Security architectures and economic cooperation The emerging Euro-Mediterranean system . . prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page iii Ben Tonra and Thomas Christiansen editors rethinking european union foreign policy Modern conflict, postmodern union Security architectures and economic cooperation MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave prelims 7/6/04 9:46 am Page iv Copyright © Manchester University Press 2004 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors. -

Preoccupied by the Past

© Scandia 2010 http://www.tidskriftenscandia.se/ Preoccupied by the Past The Case of Estonian’s Museum of Occupations Stuart Burch & Ulf Zander The nation is born out of the resistance, ideally without external aid, of its nascent citizens against oppression […] An effective founding struggle should contain memorable massacres, atrocities, assassina- tions and the like, which serve to unite and strengthen resistance and render the resulting victory the more justified and the more fulfilling. They also can provide a focus for a ”remember the x atrocity” histori- cal narrative.1 That a ”foundation struggle mythology” can form a compelling element of national identity is eminently illustrated by the case of Estonia. Its path to independence in 98 followed by German and Soviet occupation in the Second World War and subsequent incorporation into the Soviet Union is officially presented as a period of continuous struggle, culminating in the resumption of autonomy in 99. A key institution for narrating Estonia’s particular ”foundation struggle mythology” is the Museum of Occupations – the subject of our article – which opened in Tallinn in 2003. It conforms to an observation made by Rhiannon Mason concerning the nature of national museums. These entities, she argues, play an important role in articulating, challenging and responding to public perceptions of a nation’s histories, identities, cultures and politics. At the same time, national museums are themselves shaped by the nations within which they are located.2 The privileged role of the museum plus the potency of a ”foundation struggle mythology” accounts for the rise of museums of occupation in Estonia and other Eastern European states since 989. -

UNIVERISTY of TARTU Faculty of Social Sciences and Education

UNIVERISTY OF TARTU Faculty of Social Sciences and Education Centre for Baltic Studies Mariana Semenyshyn ‘Towards A Common Identity? A Comparative Analysis of Estonian Integration Policy’ Master’s thesis for International Masters Programme in Russian, Central and East European Studies Supervisor: Dr. Eva-Clarita Pettai Tartu 2014 This thesis conforms to the requirements for a Master’s thesis ...................................................................(signature of the supervisor and date) Submitted for defence ........................... .. (date) The thesis is 22. 427 words in length excluding Bibliography. I have written this Master’s thesis independently. Any ideas or data taken from other authors or other sources have been fully referenced. I agree to publish my thesis on the DSpace at University of Tartu (digital archive) and on the webpage of the Centre for Baltic Studies, UT ............................................................ (signature of the author and date) 2 ABSTRACT This thesis looks into the Estonian policies towards its Russian-speaking population within the framework of ethno-political regimes. It engages into a meta-analysis of major integration documents, namely, the State Integration Programme ‘Integration in Estonian Society 2000-2007’, the Development Plan ‘Estonian Integration Strategy 2008-2013’, and the Strategy of Integration and Social Cohesion in Estonia ‘Integrating Estonia 2020’. By focusing on the development of the ‘state identity’ concept in these documents, it evaluates changes of the ethno-political regime in Estonia. A thorough analysis of the most recent integration Programme ‘Integrating Estonia 2020’ demonstrates that Estonia is slowly moving towards more liberal vision of state identity in particular and its policies towards Russian-speakers in general. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. -

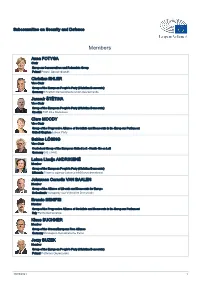

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government

London School of Economics and Political Science Department of Government Historical Culture, Conflicting Memories and Identities in post-Soviet Estonia Meike Wulf Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of London London 2005 UMI Number: U213073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U213073 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Ih c s e s . r. 3 5 o ^ . Library British Library of Political and Economic Science Abstract This study investigates the interplay of collective memories and national identity in Estonia, and uses life story interviews with members of the intellectual elite as the primary source. I view collective memory not as a monolithic homogenous unit, but as subdivided into various group memories that can be conflicting. The conflict line between ‘Estonian victims’ and ‘Russian perpetrators* figures prominently in the historical culture of post-Soviet Estonia. However, by setting an ethnic Estonian memory against a ‘Soviet Russian’ memory, the official historical narrative fails to account for the complexity of the various counter-histories and newly emerging identities activated in times of socio-political ‘transition’. -

Separatist Versus Centrist Forces in the Ussr, 1988-1991: Explaining the Collapse of the Soviet Internal Empire by a Strategic Alliance Approach

********************************************************* SEPARATIST VERSUS CENTRIST FORCES IN THE USSR, 1988-1991: EXPLAINING THE COLLAPSE OF THE SOVIET INTERNAL EMPIRE BY A STRATEGIC ALLIANCE APPROACH COMPARING THE BALTIC AND THE TRANSCAUCASIAN CASES: A PROGRESS REPORT By Caspar ten Dam ********************************************************* Seminar “Soviet Internal Empire: Establishment, Daily Working and Dissolution”, by Prof. Mette Skak ERASMUS, st.nr.923488 September 1993 Reproduced & proofread for publication: March 2015 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION: Determinism within Sovietology and Why a Strategic Alliance Approach is Chosen 4 CHAPTER 1: Aspects of Strategic Alliance 8 1.1. Alignments and Realignments among Centrist and Separatist Forces, and Types of Organization 8 1.2. Typologies of Political Groups, based on the Centrist-Separatist Divide 9 CHAPTER 2. The Baltics: Successful Separatism by Moderate Senior-Junior Partnership Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Republican Communist Parties 14 2.1. 1988: the establishments of the Popular Fronts - and Different Degrees of Cooperation with the Communist Parties 14 2.2. 1989: the Establishments of Moderate Alliances between the Popular Fronts and the Communist Parties, and the Rising Challenges of the Radical Congress Movements 17 2.3. 1990: the Moderate/Radical CP-PF Alliances fared Differently in each Republic, and the Radical Congress Alliances had Different Rates of Success 21 2.4. 1991: the Year of Allying Dangerously 25 2.5. Conclusion 30 CHAPTER 3. The Transcaucasus: Successful Ethnonationalism and Weak Separatism by Extremist Antagonistic Blocs 32 3.1. 1988: the Establishment of Nationalist Movements against the Wishes of Conservative-Reactionary Elites 32 3.2. 1989: the Rise of Extremist Nationalism, Superseding Statist Separatism, and the Failure to Establish Strategic Alliances among the Communist Parties and Opposition Movements 36 3.3. -

ABSTRACT Memory Wars and Metanarratives: the Historical

ABSTRACT Memory Wars and Metanarratives: the Historical Context of Linguistic Discrimination in Estonia Chanse E. Sonsalla Director: Adrienne Harris, Ph.D. In the 20th century, the country of Estonia was decimated, terrorized, and subjugated by the USSR. Estonians continue to redefine their national identity, but the process is complicated by the continued presence of ethnic Russians in Estonia. When 30% of a country's population speaks differently, thinks differently, and was once an enemy that instigated an era of terror, how does it rebuild? Language has been a polarizing issue between the ethnic Estonian and ethnic Russian populations as long as both have been present in Estonia. By investigating trends in language policy, this thesis explores the roots of tension between the two groups. The ultimate goal of the thesis is to provide insight into the pitfalls of post-conflict reintegration and the potential of language policy as a discriminatory instrument. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ____________________________________________ Dr. Adrienne Harris, Department of Modern Languages and Cultures APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ____________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE: _______________________ MEMORY WARS AND METANARRATIVES: THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF LINGUISTIC DISCRIMINATION IN ESTONIA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Chanse E. Sonsalla Waco, Texas May 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... -

Research Report: Selected Case-Law of the European Court of Human Rights on Young People

RESEARCH REPORT _______________________ Selected case-law of the European Court of Human Rights on young people Publishers or organisations wishing to reproduce this report (or a translation thereof) in print or online are asked to contact [email protected] for further instructions. © Council of Europe/European Court of Human Rights, 2012 The document is available for downloading at www.echr.coe.int (Case-law – Case-Law Analysis – Research Reports). This document has been prepared by the Research Division and does not bind the Court. The text was finalised in November 2012, and may be subject to editorial revision. 2 COMPILATION OF RELEVANT CASE-LAW OF THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS ON YOUNG PEOPLE Compilation of Relevant Case-law of the European Court of Human Rights on Young People between 18 and 35 Years This compilation summarises the relevant case-law of the European Court of Human Rights on specific areas of importance for young people between 18 and 35 years: - Access to a professional career (under A.) ………………………………………….. 4 Bigaeva v. Greece, no. 26713/05, 28 May 2009 - Conscientious objection (under B.) …………………………………………………. 5 Savda v. Turkey, no. 42730/05, 12 June 2012 Bayatyan v. Armenia [GC], no. 23459/03, ECHR 2011 Thlimmenos v. Greece [GC], no. 34369/97, ECHR 2000-IV Koppi v. Austria, no. 33001/03, 10 December 2009 Gütl v. Austria, no. 49686/99, 12 March 2009 Löffelmann v. Austria, no. 42967/98, 12 March 2009 Ülke v. Turkey, no. 39437/98, 24 January 2006 Autio v. Finland, no. 17086/90, Commission decision of 6.12.1991 Johansen v.