Constitutional Amendment in Palau: Democracy and Federalism at Collision Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 16 STATES

The 16 STATES Pristine Paradise. 2 Palau is an archipelago of diverse terrain, flora and fauna. There is the largest island of volcanic origin, called Babeldaob, the outer atoll and limestone islands, the Southern Lagoon and islands of Koror, and the southwest islands, which are located about 250 miles southwest of Palau. These regions are divided into sixteen states, each with their own distinct features and attractions. Transportation to these states is mainly by road, boat, or small aircraft. Koror is a group of islands connected by bridges and causeways, and is joined to Babeldaob Island by the Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge. Once in Babeldaob, driving the circumference of the island on the highway can be done in a half day or full day, depending on the number of stops you would like. The outer islands of Angaur and Peleliu are at the southern region of the archipelago, and are accessable by small aircraft or boat, and there is a regularly scheduled state ferry that stops at both islands. Kayangel, to the north of Babeldaob, can also be visited by boat or helicopter. The Southwest Islands, due to their remote location, are only accessible by large ocean-going vessels, but are a glimpse into Palau’s simplicity and beauty. When visiting these pristine areas, it is necessary to contact the State Offices in order to be introduced to these cultural treasures through a knowledgeable guide. While some fees may apply, your contribution will be used for the preservation of these sites. Please see page 19 for a list of the state offices. -

Helen Reef 2008: an Overview

Helen Reef 2008: an Overview by Patrick L. Colin, Lori J. Bell and Sharon Patris Coral Reef Research Foundation P.O. Box 1765 Koror, Palau 96940 [email protected] Technical Report 2008 © Coral Reef Research Foundation Suggested citation: Colin, P.L., L.J. Bell and S. Patris. 2008. Helen Reef 2008: An Overview. Technical Report, Coral Reef Research Foundation, 31pp. www.coralreefpalau.org CORAL REEF RESEARCH FOUNDATION Report to Helen Reef Project SW Islands Collecting Trip, Sept 2008 INTRODUCTION In September 2008 the Coral Reef Research Foundation (CRRF) participated in a 3 week trip to Sonsorol and Hatohobei States for the purpose of marine invertebrate collections for the US National Cancer Institute (NCI). In addition to the NCI collections we were able to make a considerable number of general observations about marine conditions as well as gather a variety of data on tides, currents and temperatures at Helen Reef. The trip was a shared charter aboard the live-aboard dive boat Pacific Explorer II, in conjunction with fish biologists Rick Winterbottom (Royal Ontario Museum, Canada) and Mark Westneat (Field Museum, Chicago), from 10 – 29 September 2008. This report is intended to summarize the observations and collections made by CRRF. Two previous small collections were made in the Southwest Islands by CRRF, July 1995 to Sonsorol State, and December 1996 to Hatohobei State. Some of those results are summarized here for continuity in data. The Southwest Islands of Palau represent an area which is intermediate between the ultra diverse "Coral Triangle" (Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, Malaysia, Solomon Islands, Philippines) and the less (but still very high) diverse Micronesian islands. -

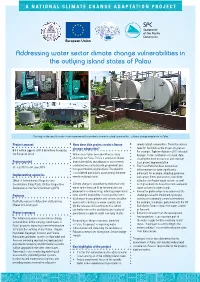

Addressing Water Sector Climate Change Vulnerabilities in the Outlying Island States of Palau

A NATIONAL CLIMATE CHANGE ADAPTATION PROJECT Global Climate Change Alliance Addressing water sector climate change vulnerabilities in the outlying island states of Palau Focusing on the specific water issues experienced by residents in remote island communities – climate change adaptation in Palau. Project amount How does this project assist climate remote island communities. There has been a change adaptation? need for flexibility as the project progresses. € 0.5 million (approx. USD 0.66 million) funded by For example, Typhoon Haiyan in 2013 affected the European Union Water security has been identified as a key Kyangel, Palau’s northernmost island state, challenge for Palau. This is a conclusion drawn creating the need to reassess and redesign Project period from vulnerability and adaptation assessments local project implementation. conducted in-country by both government and 31 July 2013 to 30 June 2015 • The Palau Public Utilities Corporation non-governmental organisations. The problem infrastructure has been significantly is considered particularly acute among the more enhanced. For example, a backup generator Implementing agencies remote outlying islands. and carbon filters and aerators have been Office of Environmental Response and added to the Angaur water system, as well Coordination; Palau Public Utilities Corporation Climate change is exacerbating problems in the as improvements to household and communal Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) water sector because (i) air temperatures are water systems in other islands. projected to continue rising, affecting evaporation • Innovative partnerships have addressed the Partners rates and the availability of good quality water; challenges faced in implementing project (ii) changes in precipitation and extreme weather activities in extremely remote communities. -

“There Is No Place Like Home”

stephanie walda-mandel “There is no place Migration and Cultural Identity like home” of the Sonsorolese, Micronesia HEIDELBERG STUDIES IN PACIFIC ANTHROPOLOGY 5 heidelberg studies in pacific anthropology Volume 5 Edited by jürg wassmann stephanie walda-mandel “T here is no place like home” Migration and Cultural Identity of the Sonsorolese, Micronesia Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Diese Veröffentlichung wurde als Dissertation im Jahr 2014 unter dem Titel “There’s No Place Like Home”: Auswirkungen von Migration auf die kulturelle Identität von Sonsorolesen im Fach Ethnologie an der Fakultät für Verhaltens- und Empirische Kulturwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg angenommen. cover: Father and son on the way to Sonsorol © S. Walda-Mandel 2004 isbn 978-3-8253-6692-6 Dieses Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt ins- besondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. © 2016 Universitätsverlag Winter GmbH Heidelberg Imprimé en Allemagne · Printed in Germany Umschlaggestaltung: Klaus Brecht GmbH, Heidelberg Druck: Memminger MedienCentrum, -

A Guide to Palau's Conservation and Protected Areas 2017

A Guide to Palau’s Conservation and Protected Areas The Culture of Pristine Paradise Palau Table of Context • The Republic of Palau • Biodiversity • Kayangel • Ngarchelong • Ngaraard • Ngardmau • Aimeliik • Ngchesar • Airai • Koror • Peliliu • Hatohobei • PAN map Introduction The Republic of Palau Is located in the Northwest Pacific just North of Indonesia and West of the Philippines. The land area which is comprised of more 700 islands covers 189 sq. miles of land area including the rock islands and has an exclusive economic zone extending over 237,850 sq miles. The island is home to 20,000 inhabitants and a vibrant marine and terrestrial environment. With over 7,000 terrestrials and 10,000 marine species known to exist in the country. Biodiversity Palau has the most terrestrial biodiversity in the Micronesia region, and one of the most biologically diverse underwater environments globally. Approximately 1,000 endemic species are found in Palau. It has approximately 200 endemic plant species including 60 species of orchids. Palau also has around 300 terrestrial gastropods, 500 types of insects and 16 species of birds and 2 species of bats. It is also home to 12 species of amphibians, reptiles, freshwater fish and the endangered Palau Megapode. Palau is also home to more than 350 species of hard corals, 200 species of soft corals, over 300 species of sponges and more than 1,300 species of fish. Its waters are also home to endangered and vulnerable species such as the dugong, saltwater crocodile, hawksbill and green turtles, and giant clams. There are also over 60 marine lakes, five of them being home to the jellyfish. -

Wikipedia on Palau

Palau From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the country. For other uses, see Palau (disambiguation). Republic of Palau Beluu ęr a Belau Flag Seal Anthem: Belau loba klisiich er a kelulul Palau is circled in green. Melekeok[1] Capital 7°21′N 134°28′E Largest city Koror Official language(s) English Palauan Japanese (in Angaur) Recognised regional languages Sonsorolese (in Sonsoral) Tobian (in Hatohobei) Demonym Palauan Government Unitary presidential democratic republic - President Johnson Toribiong - Vice President Kerai Mariur Legislature National Congress Independence 2 Compact of Free - Association with United October 1, 1994 States Area 2 - Total 459 km (196th) 177 sq mi - Water (%) negligible Population - 2011 estimate 20,956 (218th) 2 - Density 28.4/km 45.5/sq mi GDP (PPP) 2008 estimate [2] - Total $164 million (2008 est.) (not ranked) - Per capita $8,100[2] (119th) HDI (2011) 0.782[3] (high) (49th) Currency United States dollar (USD) Time zone (UTC+9) Drives on the right ISO 3166 code PW Internet TLD .pw Calling code +680 On October 7, 2006, government officials moved their offices in the former capital of Koror to Ngerulmud in 1State of Melekeok, located 20 km (12 mi) northeast of Koror on Babelthaup Island and 2 km (1 mi) northwest of Melekeok village. 2GDP estimate includes US subsidy (2004 estimate). Palau ( i/pəˈlaʊ/, sometimes spelled Belau or Pelew), officially the Republic of Palau (Palauan: Beluu ęr a Belau), is an island country located in the western Pacific Ocean. Geographically part of the larger island group of Micronesia, with the country’s population of around 21,000 people spread out over 250 islands forming the western chain of the Caroline Islands. -

Helen Reef and the Hatohobei Community

Helen Reef and the Hatohobei Community: SEM-Pasifika Socioeconomic Assessment Report Conducted and supported by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Coral Reef Conservation Program, Palau International Coral Reef Center (PICRC), and Helen Reef Resource Management Office (HRRMP) Lead author: Noelle Wenty Oldiais Co-authors: Alson Ngiraiwet, Bradley Patris, Bruce Ngirkuteling, Claire Polloi, Davis Rekemsiik, Dawnette Olsudong, Elwais Samil, Felisa Andrew, Isao Frank, Ismael Bernado, Japson Yoshiwo, King Sam, Ngirachues Aderkeroi, Noelle Wenty Oldiais, Tracy Marcello, Umai Basilius, Verano Ngirkelau, Victor R. Masahiro, and William Andrew NOAA Advisors: Christy Loper and Meghan Gombos Editors: Noelle Wenty Oldiais and Christy Loper Recommended citation: Oldiais, NW. 2009. Helen Reef and Hatohobei Community: SEM-Pasifika Socioeconomic Assessment Report. Palau International Coral Reef Center. Hard and/or electronic copies can be requested from: Noelle Wenty Oldiais Palau International Coral Reef Center PO BOX 7086 Koror, Palau 96940 Phone: (680) 488-6950 Fax: (680) 488-6951 [email protected] Downloadable copies can be found at: www.socmon.org Cover photo: Logo of Helen Reef Resource Management Office Photo credit: Helen Reef Resource Management Office 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Messages ……………………………….…………………………………………………….…4 2 Acknowledgements......................................................................................................................6 3 Executive summary……………………………………………..……………………………...6 4 Introduction………………………………………….………………………………………....7 -

Improving the Management of Helen Reef

“Sustainable Management at Helen Reef, Palau” Final Narrative Report to The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation Award # 2006-0090-021 Reporting Period: September 1, 2006 – December 31, 2008 Date: September 27, 20101 Prepared and Submitted by: Wayne Andrew, Chairman The Helen Reef Resource Management Program Hatohobei State, Republic of Palau Michael Guilbeaux Former International Program Director The Community Conservation Network Honolulu, Hawaii, USA 1 There was a significant delay in reporting on the activities and outcomes of this project due to: 1) difficulties in receiving timely and adequate financial information from the site implementing program, the Helen Reef Resource Management Program (HRRMP), and 2) in January 2009 the dissolution of the Community Conservation Network. Since these events, project principals Wayne Andrew, former HRRMP Program Manager and current chairman of the HRRMP Management Board, and Michael Guilbeaux, former CCN International Program Director, have worked together to prepare the following report based on available information. 1 Sustainable Management at Helen Reef, Palau NFWF Award # 2006-0090-021 INTRODUCTION Helen Reef is a large coral reef atoll located in the remote Southwest Islands of Palau, close to the north coast of West Papua, Indonesia. The people and State of Hatohobei, the owners of Helen Reef, have made attempts for several decades to protect and manage the atoll’s coral reef’s marine resources. However, they have faced significant challenges in finding workable solutions to threats to the atoll’s resources and biodiversity, such as foreign poaching and unsustainable harvesting practices at the site. New management strategies were initiated at Helen Reef in 2002 with the enactment of State legislation declaring a Marine Conservation Area at the site. -

Final Report Palau Integrated Marine Protected Area Model

Palau Integrated Marine Protected Area Model The Final Report of The Project for Exploratory Research on Models of a Micronesian Marine Protected Area FY 2010-2011 The Sasakawa Peace Foundation The Sasakawa Pacific Island Nations Fund CopyrightⒸ 2013 by The Sasakawa Peace Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the permission of the publisher, except for the purpose of a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, broadcast or online service. The Sasakawa Pacific Island Nations Fund, The Sasakawa Peace Foundation The Nippon FoundationBldg., 4th Fl. 1-2-2, Akasaka, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan Phone: +81-3-6229-5450 Fax: +81-3-6229-5473 URL: http://www.spf.org/spinf/ Edited by Chihiro Sato, Administrative Staff, SPINF Junichi Koyanagi, Program officer, SPINF Supported by Yuriko Hasegawa, Assistant Manager, SPINF Printed at Tobi Co.,Ltd., Tokyo, Japan Contents Foreword The Micronesia Marine Environment Committee Members Glossary Chapter 1 Project Overview ··············································································································································· 1 1.1 Background and Objectives ·························································································································· 1 1.2 Scope and Content of Project Implementation ··························································································· 2 1.2.1 Establishment of the Micronesia Marine Environment -

1 Palau Country Profile

1 Palau Country Profile Page 1 Page 2 General Information Palau (historically Belau or Pelew), officially the Republic of Palau, is an island country located in the western Pacific Ocean. The country is made up of approximately 340 islands, forming the western chain of the Caroline Islands in Micronesia. It has an area of 466 square kilometres (180 sq. mi). The most populous island is Koror. The capital Ngerulmud is located on the nearby island of Babeldaob, in Melekeok State. Palau shares maritime boundaries with In donesia, the Philippines, and the Federated States of Micronesia. Palau's economy is based mainly on tourism, subsistence agriculture and fishing, with a significant portion of gross national product (GNP) derived from foreign aid. The country uses the United States Dollar (USD) as its currency. The islands' culture mixes Micronesian, Melanesian, Asian, and Western elements. Ethnic Palauans, the majority of the population, are of mixed Micronesian, Melanesian, and Austronesian descent. A smaller proportion of the population is descended from Japanese and Filipino settlers. The country's two official languages are Palauan (a member of the wider Sunda–Sulawesi language group) and English, with Japanese, Sonsorolese, and Tobian recognised as regional languages. Politically, Palau is a presidential republic in free association with the United States, which provides defense, funding, and access to social services. Legislative power is concentrated in the bicameral Palau National Congress. States of Palau State Capital Area (km2) -

Biodiversity Planning for Palau's Protected Areas Network

May 2007 TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No 1/07 Biodiversity Planning for Palau’s Protected Areas Network An Ecoregional Assessment Prepared by: David Hinchley, Geoff Lipsett-Moore, Stuart Sheppard, Umiich Sengebau, Eric Verheij and Sean Austin Supported by: Ngatpang State, Sonsorol State and Hatohobei State May 2007 TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No 1/07 Biodiversity Planning for Palau’s Protected Areas Network An Ecoregional Assessment Prepared by: David Hinchley, Geoff Lipsett-Moore, Stuart Sheppard Umiich Sengebau, Eric Verheij and Sean Austin Published by: The Nature Conservancy, Indo-Pacific Resource Centre Author Contact Details: Geoff Lipsett-Moore: The Nature Conservancy, 51 Edmondstone Street, South Brisbane, QLD 4101 Australia, email: [email protected] Umiich Sengebau: The Nature Conservancy, Palau Field Office, Salii Building, Malakal, P.O. Box 1738, Koror, PW 96940, Republic of Palau, email: [email protected] Sean C. Austin: The Nature Conservancy, Palau Field Office, Salii Building, Malakal, P.O. Box 1738, Koror, PW 96940, Republic of Palau, email: [email protected] Eric Verheij: The Nature Conservancy, Palau Field Office, Salii Building, Malakal, P.O. Box 1738, Koror, PW 96940, Republic of Palau, email: [email protected] Suggested Citation: Hinchley, D., Lipsett-Moore, G., Sheppard, S., Sengebau, F.U., Verheij, E., and Austin S. (2007). Biodiversity Planning for Palau’s Protected Areas Network: An Ecoregional Assessment. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 1/07. Disclaimer: All areas identified in the assessment as important for conservation and management represent a synthesis of the best available scientific information. However, all decisions relating to the conservation and management of these areas is entirely at the discretion of the Palau people and their State and National Governments. -

Republic of Palau

0 Republic of Palau W @ r P tuFublic of Palau Stote Of the Environment Report 1994 USP [,i brary Cotalog;uing-irr-Publicarion data: Otobe{ Demei O. and Maiara, losefa A. Republic of Palau r $tate {rf tlte environm:ent. repol.t; Western Sdnroa: SPREP" f99al. -IApia, n'iii;89p.;99em "Prod,uced rsith firrancial assistaqc€ ['rom the United Ft$ations Developmerrt Progranme (UNDP) " r$BN 982-0+0097-X l. Ewlronmental policy-Palart 2. Enr4rtrmuelrtal prorection-Pslatr 3, Perlart-Ettvirorrmental condition,s t. Otob-ed, Demei O. II. Maiara, IosefaA. III. Srrtrth Pacific Regional Environnrent Prog,r'arrune M Title HCru.n5P2R46 3$3. 7r 5099{i6 Prepared fcr prb,licatiorl by the South Pacific Regio nd Erlvilonnrenl Prtrgrarrrrne, Apa, Western Samoa O Sourh Pacilic Rggional Environment Pro.gryaqme, 1994 The Sottth Pbcifie Regicrnal Entironrneut Prograli:lre authorises the reprodustion of textllal niaterial, whole,or part, in any fonn," provided apprOpriate ackno$ledgeflrcnt h girr€n. eoordinating editrry ,Strztn'ne'Crrano l-ditor Barbara Heuson Desigrr and production Peter Erarrs Artwork for qvmbols Crrtherine Appleton Drlg<rng drawings reproduced counesy of Divisiou of Marine Resources Photography Demai Otobedand Ertvironmerrtal Qpalitv Protection Board C<n'er desigrr by Feter Elzurs based ort an origi:ual desigrr by Gatherine Appletpn Map* suppliecl by MAP,graphisr, Btisbane, Australia Typert in New Baskerville und Gill Sarrs Prlnted on I l0,gsrn Tudor R. P (1007o rew,cled) by ABC Frindng, Brisbane,,rArulralia; Illustratilr nratefial.canRot be reprocluce<l'*,ilhout penr Lssion of lhe,artisr or: photcrgraBher. Produced with fuancial agsistance from tte Urritcd Nadqos Development Pr.ogramme'ruI{DF) Cm,rrfiltotogtartk: Ngn:ewarluu Bat, one aJ'lhr lnrgrt rnaa$al ba\ eeos't,;tpant i'n M'irmnesilt (phttto r'SrtotltnaX (uxrlry af (lral l)mtit:ozunm,lnl il-t hotetlian Bnatil ) Rcpublic of Palau St ate Of the Environment Re port r994 by Demei O.