Representations of Agricultural Labour in Randidangazhi K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Co-Operative Societies in Black Clam Fishery and Trade in Vembanad Lake

6 Marine Fisheries Information Service T&E Ser., No. 207, 2011 Role of co-operative societies in black clam fishery and trade in Vembanad Lake N. Suja and K. S. Mohamed Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi Lime shells and live clams are distributed in large quantities in the backwaters and estuaries of Kerala. Vembanad, the largest lake of Kerala, also holds a vast resource of lime shells and live clam, comprising several species. The major species that account for the clam fishery of Vembanad Lake is the black clam Villorita cyprinoides. The lime shells that contribute to the fishery are broadly classified as the ‘white shells’ and the ‘black shells’. The so-called ‘white shells’ are sub-soil deposits of fossilized shells and are known to extend upto 7 feet below the lake bottom. The black shells are obtained from the living population of V. cyprinoides, which contribute more than 90% of the clams from this lake. The lime shell is mainly used for the manufacture of cement, calcium carbide and sand lime bricks. They are also used for lime burning, for construction, in paddy field / fish farms for neutralizing acid soil and as slaked lime. This is used as a raw material for the manufacture of distemper, glass, rayon, paper and sugar. Shell Control Act The Government of India has listed lime shell as a minor mineral under the Mineral Concession Fig. 1. Location of black clam lime shell industrial co-operative Rules, 1949, Section 5 of the Mines and Minerals. societies The acquisition, sale, supply and distribution of lime shell in the State are at present controlled by Black clam lime shell industrial co-operative the Kerala Lime Shells Control Act, 1958. -

Case Study2 Niche Tourism Marketing

IIUM Journal of Case Studies in Management: Vol. 1: 23-35, 2010 ISSN 2180-2327 Case Study2 Niche Tourism Marketing Manoj Edward Cochin University of Science and Technology, India Babu P George* University of Southern Mississippi, USA Abstract: This case study focuses on a niche tourism operator in Kerala, India, offering tour packages mainly in the areas of adventure and ecotourism. The operation began in 2000, and by 2008 had achieved considerable growth mainly due to the owners’ steadfast commitment and passionate approach to the product idea being promoted. Over the years, the firm has witnessed many changes in terms of modifying the initial idea of the product to suit market realities such as adding new services and packages, expanding to new markets, and starting of new ventures in related areas. In the process, the owners have faced various challenges and tackled most them as part of pursuing sustained growth. The present case study aims to capture these growth dynamics specific to entrepreneurship challenges. Specific problems in the growth stage like issues in designing an innovative niche product and delivering it with superior quality, coordinating with an array of suppliers, and tapping international tourism markets with a limited marketing budget, are explored in this study. Also, this study explores certain unique characteristics of the firm’s operation which has a bearing on the niche area it operates. Lastly, some of the critical issues pertaining to entrepreneurship in the light of the firm’s future growth plans are also outlined. INTRODUCTION Kalypso Adventures is a package tour company that was started in 2000 by two Naval Commanders of the Indian Navy, Cdr. -

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: a Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels

Love and Marriage Across Communal Barriers: A Note on Hindu-Muslim Relationship in Three Malayalam Novels K. AYYAPPA PANIKER If marriages were made in heaven, the humans would not have much work to do in this world. But fornmately or unfortunately marriages continue to be a matter of grave concern not only for individuals before, during, and/ or after matrimony, but also for social and religious groups. Marriages do create problems, but many look upon them as capable of solving problems too. To the poet's saying about the course of true love, we might add that there are forces that do not allow the smooth running of the course of true love. Yet those who believe in love as a panacea for all personal and social ills recommend it as a sure means of achieving social and religious integration across caste and communal barriers. In a poem written against the backdrop of the 1921 Moplah Rebellion in Malabar, the Malayalam poet Kumaran Asan presents a futuristic Brahmin-Chandala or Nambudiri-Pulaya marriage. To him this was advaita in practice, although in that poem this vision of unity is not extended to the Muslims. In Malayalam fi ction, however, the theme of love and marriage between Hindus and Muslims keeps recurring, although portrayals of the successful working of inter-communal marriages are very rare. This article tries to focus on three novels in Malayalam in which this theme of Hindu-Muslim relationship is presented either as the pivotal or as a minor concern. In all the three cases love flourishes, but marriage is forestalled by unfavourable circumstances. -

Language and Literature

1 Indian Languages and Literature Introduction Thousands of years ago, the people of the Harappan civilisation knew how to write. Unfortunately, their script has not yet been deciphered. Despite this setback, it is safe to state that the literary traditions of India go back to over 3,000 years ago. India is a huge land with a continuous history spanning several millennia. There is a staggering degree of variety and diversity in the languages and dialects spoken by Indians. This diversity is a result of the influx of languages and ideas from all over the continent, mostly through migration from Central, Eastern and Western Asia. There are differences and variations in the languages and dialects as a result of several factors – ethnicity, history, geography and others. There is a broad social integration among all the speakers of a certain language. In the beginning languages and dialects developed in the different regions of the country in relative isolation. In India, languages are often a mark of identity of a person and define regional boundaries. Cultural mixing among various races and communities led to the mixing of languages and dialects to a great extent, although they still maintain regional identity. In free India, the broad geographical distribution pattern of major language groups was used as one of the decisive factors for the formation of states. This gave a new political meaning to the geographical pattern of the linguistic distribution in the country. According to the 1961 census figures, the most comprehensive data on languages collected in India, there were 187 languages spoken by different sections of our society. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Marxist Praxis: Communist Experience in Kerala: 1957-2011

MARXIST PRAXIS: COMMUNIST EXPERIENCE IN KERALA: 1957-2011 E.K. SANTHA DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SIKKIM UNIVERSITY GANGTOK-737102 November 2016 To my Amma & Achan... ACKNOWLEDGEMENT At the outset, let me express my deep gratitude to Dr. Vijay Kumar Thangellapali for his guidance and supervision of my thesis. I acknowledge the help rendered by the staff of various libraries- Archives on Contemporary History, Jawaharlal Nehru University, C. Achutha Menon Study and Research Centre, Appan Thampuran Smaraka Vayanasala, AKG Centre for Research and Studies, and C Unniraja Smaraka Library. I express my gratitude to the staff at The Hindu archives and Vibha in particular for her immense help. I express my gratitude to people – belong to various shades of the Left - who shared their experience that gave me a lot of insights. I also acknowledge my long association with my teachers at Sree Kerala Varma College, Thrissur and my friends there. I express my gratitude to my friends, Deep, Granthana, Kachyo, Manu, Noorbanu, Rajworshi and Samten for sharing their thoughts and for being with me in difficult times. I specially thank Ugen for his kindness and he was always there to help; and Biplove for taking the trouble of going through the draft intensely and giving valuable comments. I thank my friends in the M.A. History (batch 2015-17) and MPhil/PhD scholars at the History Department, S.U for the fun we had together, notwithstanding the generation gap. I express my deep gratitude to my mother P.B. -

Members of the Local Authorities Alappuzha District

Price. Rs. 150/- per copy UNIVERSITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate by the member of the Local Authorities- (Under Section 17-Elected Members (7) of the Kerala University Act 1974) Electoral Roll of the Members of the Local Authorities-Alappuzha District Name of Roll Local No. Authority Name of member Address 1 LEKHA.P-MEMBER SREERAGAM, KARUVATTA NORTH PALAPPRAMBILKIZHAKKETHIL,KARUVATTA 2 SUMA -ST. NORTH 3 MADHURI-MEMBER POONTHOTTATHIL,KARUVATTA NORTH 4 SURESH KALARIKKAL KALARIKKALKIZHAKKECHIRA, KARUVATTA 5 CHANDRAVATHY.J, VISHNUVIHAR, KARUVATTA 6 RADHAMMA . KALAPURAKKAL HOUSE,KARUVATTA 7 NANDAKUMAR.S KIZHAKKEKOYIPURATHU, KARUVATTA 8 SULOCHANA PUTHENKANDATHIL,KARUVATTA 9 MOHANAN PILLAI THUNDILVEEDU, KARUVATTA 10 Karuvatta C.SUJATHA MANNANTHERAYIL VEEDU,KARUVATTA 11 K.R.RAJAN PUTHENPARAMBIL,KARUVATTA Grama Panchayath Grama 12 AKHIL.B CHOORAKKATTU HOUSE,KARUVATTA 13 T.Ponnamma- ThaichiraBanglow,Karuvatta P.O, Alappuzha 14 SHEELARAJAN R.S BHAVANAM,KARUVATTA NORTH MOHANKUMAR(AYYAPP 15 AN) MONEESHBHAVANAM,KARUVATTA 16 Sosamma Louis Chullikkal, Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 17 Jayamohan Shyama Nivas, Pollethai.P.O 18 Kala Thamarappallyveli,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 19 Dinakaran Udamssery,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 20 Rema Devi Puthenmadam, Kalvoor. P.O, Alappuzha 21 Indira Thilakan Pandyalakkal, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 22 V. Sethunath Kunnathu, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 23 Reshmi Raju Rajammalayam, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 24 Muthulekshmi Castle, Pathirappaly.P.O, Alappuzha 25 Thresyamma( Marykutty) Chavadiyil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 26 Philomina (Suja) Vadakkan parambil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha Grama Panchayath Grama 27 South Mararikulam Omana Moonnukandathil, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 28 Alice Sandhyav Vavakkad, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 29 Laiju. M Madathe veliyil , Pathirappally P O 30 Sisily (Kunjumol Shaji) Puthenpurakkal, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 31 K.A. -

Translation, Religion and Culture

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:1 January 2019 India’s Higher Education Authority UGC Approved List of Journals Serial Number 49042 ==================================================================== Translation, Religion and Culture T. Rubalakshmy =================================================================== Abstract Translation is made for human being to interact with each other to express their love, emotions and trade for their survival. Translators often been hidden into unknown characters who paved the road way for some contribution. In the same time being a translator is very hard and dangerous one. William Tyndale he is in Holland in the year 1536 he worked as a translating the Bible into English. Human needs to understand the culture of the native place where they live. Translator even translates the text and speak many languages. Translators need to have a good knowledge about every language. Translators can give their own opinion while translating. In Malayalam in the novel Chemmeen translated in English by Narayanan Menon titled Chemmeen. This paper is about the relationship between Karuthamma and Pareekutty. Keywords: Chemmeen, translation, languages, relationship, culture, dangerous. Introduction Language is made for human beings. Translating is not an easy task to do from one language to another. Translation has its long history. While translating a novel we have different cultures and traditions. We need to find the equivalent name of a word in translating language. The language and culture are entwined and inseparable Because in many books we have a mythological character, history, customs and ideas. So we face a problem like this while translating a work. Here Thakazhi Sivasankara Pillai also face many problems during translating a work in English . -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 10.05.2020To16.05.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 10.05.2020to16.05.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police Sl. No. father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cr No-505 /2020 U/S188, 269 IPC & Sec. 4(2)(a) r/w 5 1 of Kerala Epidemic Kudappurakizakka 16-05- Diseases Aneeshkum 37 thil,Kozhuvallor Kollakadav 2020 Ordinance BAILED ar Chellapan Male Po,Mulakazha u 21:12 2020 VENMANI Pradeep S BY POLICE Veliyil Nikarth Trichattukulam 16-05- Cr No-824 2 63 P.o Panavally Trichattuku 2020 /2020 U/S15 POOCHAK Mithran BAILED Mohanan Kesavan Male P/W-4 lam 20:24 of KG Act AL K.M BY POLICE Kuzhikkattuchira Trichattukulam 16-05- Cr No-824 3 Pushpanga 39 P.O Panavally Trichattuku 2020 /2020 U/S15 POOCHAK Mithran BAILED Anilkumar dhan Male P/W-4 lam 20:24 of KG Act AL K.M BY POLICE Vattachira Trichattukulam 16-05- Cr No-824 4 38 P.O Panavally Trichattuku 2020 /2020 U/S15 POOCHAK Mithran BAILED Sajeev Raghavan Male P/W-4 lam 20:24 of KG Act AL K.M BY POLICE Kuzhiparambil Trichattukulam 16-05- Cr No-824 5 56 P.o Panavally Trichattuku 2020 /2020 U/S15 POOCHAK Mithran BAILED Vijayan Kumaran Male P/W-4 lam 20:24 of KG Act AL K.M BY POLICE thai parambu, Cr No-573 Bappu vaidyar Jn, 16-05- /2020 6 26 Canal ward, zakkariya 2020 U/S279,194( ALAPPUZ KABEER BAILED Azeem Koyamon Male Alappuzha bazar 20:00 D) of MV Act HA SOUTH C E BY POLICE Cr No-543 /2020 U/S188 Ipc 118(e) -

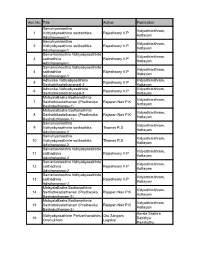

Library Stock.Pdf

Acc.No. Title Author Publication Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 1 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 2 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 3 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 4 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-1 Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 5 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam Adhunika Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 6 Rajeshwary V.P Saithathikadisthanangal-2 Kottayam MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 7 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 8 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-1) Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 9 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samuhyashasthra Vidyarthimithram, 10 Vidhyabyasathinte saithadhika Thomas R.S Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 11 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 12 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 Samaniashasthra Vidhyabyasathinte Vidyarthimithram, 13 saithadhika Rajeshwary V.P Kottayam Adisthanangal-2 MalayalaBasha Bodhanathinte Vidyarthimithram, 14 Saithathikadisthanam (Pradhesika Rajapan Nair P.K Kottayam Bashabothanam-2) MalayalaBasha -

Accused Persons Arrested in Alappuzha District from 23.05.2021To29.05.2021

Accused Persons arrested in Alappuzha district from 23.05.2021to29.05.2021 Name of Name of the Name of the Place at Date & Arresting Court at Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Sec Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, which No. Accused Sex of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PALLIKATHAYYIL,PAT 28-05-2021 Cr. 353 279 ALAPPUZHA K.P.SAJEEV SI JFCM 1 1 SREEKUTTAN STALIN Male 21 HIRAPALLY P CHETTIKAD 18:35 IPC NORTH OF POLICE ALAPPUZHA O,ALAPPUZHA KIZHAKKE Cr. 410 JFMC PANKAJAKSHA MULLASSSERI, 28-05-2021 AMBALAPUZH HASHIM. KH, 2 RENJITH Male 34 KARUMADY 4(2)(a), 4(i), AMBALAPUZH N KARUMADI, 17:05 A SI OF POLICE 4(ii) KEDO A THAKAZHY P/W 2 PUTHUVAL HOUSE, Cr. 409 11, ADDL. ABDHUL KAKKAZHOM, 28-05-2021 11(iii), 12 AMBALAPUZH SHAJI.S.NAIR, SESSIONS 3 KUNJUMON Male 41 KAKKAZHOM MANAF AMBALAPUZHA 07:30 POCSO 75 JJ A SI OF POLICE COURT II SOUTH P/W 1 ACT, 323 IPC ALAPPUZHA Cr. 407 6 r/w JFMC PAZHAYA PURAKKAD , 27-05-2021 AMBALAPUZH HASHIM. KH, 4 ANEESH BABU Male 37 PURAKKAD 24 of COTPA AMBALAPUZH PURAKKAD P/W 18 11:25 A SI OF POLICE Act A KUNJUCHIRAYIL, JFMC ABDHUL 26-05-2021 Cr. 406 4(2)(e) AMBALAPUZH HASHIM. KH, 5 SUNEER Male 30 KUNNUMMA MURI, THAKAZHY AMBALAPUZH SUNEER 20:35 , 3(b) KEDO A SI OF POLICE THAKAZHY P/W 10 A MUHAMMED KOCHUPARAMBU, JFMC ABDHUL 26-05-2021 Cr.