Nber Working Paper Series Forty Years of Latin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capitalists and Revolution

CAPITALISTS AND REVOLUTION Rose J. Spalding Working Paper #202 - March 1994 Rose J. Spalding, residential fellow at the Institute during the fall semester 1991, is Associate Professor of Political Science at DePaul University. Her publications include The Political Economy of Revolutionary Nicaragua (Boston: Allen and Unwin, 1987) and Capitalists and Revolution: Opposition and Accommodation in Nicaragua, 1979-1992 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming 1994). Research for this paper was conducted with support from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and University Research Council of DePaul University, the Social Science Research Council and American Council of Learned Societies, and the Heinz Endowment. ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between the state and the economic elite during four cases of structural reform. Analyzing state-capital relations in Chile under the Allende government, El Salvador following the 1979 reforms, Mexico during the Cárdenas era, and Peru under the Velasco regime, the author finds substantial variation in the ways in which the business elite responded to state-led reform efforts. In the first two cases, the bourgeoisie tended to unite in opposition to the regime; in the second two, it was relatively fragmented and notable sectors sought an accommodation with the regime. To explain this variation, the paper focuses on the role of five factors: the degree to which class hegemony is exercised by a traditional oligarchy; the level of organizational autonomy attained by business elites; the perception of a class-based threat; the degree to which the regime consolidates politically; and the viability of the economic model introduced by the reform regime. -

United States Cold War Policy, the Peace Corps and Its Volunteers in Colombia in the 1960S

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s. John James University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation James, John, "United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3630. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3630 UNITED STATES COLD WAR POLICY, THE PEACE CORPS AND ITS VOLUNTEERS IN COLOMBIA IN THE 1960s by J. BRYAN JAMES B.A. Florida State University, 1994 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2008 ABSTRACT John F. Kennedy initiated the Peace Corps in 1961 at the height of the Cold War to provide needed manpower and promote understanding with the underdeveloped world. This study examines Peace Corps work in Colombia during the 1960s within the framework of U.S. Cold War policy. It explores the experiences of volunteers in Colombia and contrasts their accounts with Peace Corps reports and presentations to Congress. -

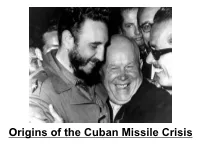

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’S Thesis “It Is Not Enough for the State That Wishes to Maintain Peace and the Status Quo to Have Superior Power

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’s Thesis “It is not enough for the state that wishes to maintain peace and the status quo to have superior power. The [Cuban Missile] Crisis came because the more powerful state also had a leader who failed to convince his opponent of his will to use its power for that purpose” (548). Background • 1/1/1959 – Castro deposes Fulgencio Batista – Still speculation as to whether he was Communist (452) • Feb. 1960 – USSR forges diplomatic ties w/ Castro – July – CUB seizes oil refineries b/c they refused to refine USSR crude • US responds by suspending sugar quota, which was 80% of Cuban exports to USà By October, CUB sells sugar to USSR & confiscates nearly $1B USD invested in CUBà • US implements trade embargo • KAGAN: CUB traded one economic subordination for another (453) Response • Ike invokes Monroe Doctrineà NK says it’s dead – Ike threatens missile strikes if CUB is violated – By Sept. 1960, USSR arms arrive in CUB – KAGAN: NK takes opportunity to reject US hegemony in region; akin to putting nukes in HUN 1956 (454) Nikita, Why Cuba? (455-56) • NK is adventuresome & wanted to see Communism spread around the world • Opportunity prevented itself • US had allies & bases close to USSR. Their turn. • KAGAN: NK was a “true believer” & he was genuinely impressed w/ Castro (456) “What can I say, I’m a pretty impressive guy” – Fidel Bay of Pigs Timeline • March 1960 – Ike begins training exiles on CIA advice to overthrow Castro • 1961 – JFK elected & has to live up to campaign rhetoric against Communism he may not have believed in (Arthur Schlesinger qtd. -

Modern Monetary Theory: Cautionary Tales from Latin America

Modern Monetary Theory: Cautionary Tales from Latin America Sebastian Edwards* Economics Working Paper 19106 HOOVER INSTITUTION 434 GALVEZ MALL STANFORD UNIVERSITY STANFORD, CA 94305-6010 April 25, 2019 According to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) it is possible to use expansive monetary policy – money creation by the central bank (i.e. the Federal Reserve) – to finance large fiscal deficits that will ensure full employment and good jobs for everyone, through a “jobs guarantee” program. In this paper I analyze some of Latin America’s historical episodes with MMT-type policies (Chile, Peru. Argentina, and Venezuela). The analysis uses the framework developed by Dornbusch and Edwards (1990, 1991) for studying macroeconomic populism. The four experiments studied in this paper ended up badly, with runaway inflation, huge currency devaluations, and precipitous real wage declines. These experiences offer a cautionary tale for MMT enthusiasts.† JEL Nos: E12, E42, E61, F31 Keywords: Modern Monetary Theory, central bank, inflation, Latin America, hyperinflation The Hoover Institution Economics Working Paper Series allows authors to distribute research for discussion and comment among other researchers. Working papers reflect the views of the author and not the views of the Hoover Institution. * Henry Ford II Distinguished Professor, Anderson Graduate School of Management, UCLA † I have benefited from discussions with Ed Leamer, José De Gregorio, Scott Sumner, and Alejandra Cox. I thank Doug Irwin and John Taylor for their support. 1 1. Introduction During the last few years an apparently new and revolutionary idea has emerged in economic policy circles in the United States: Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). The central tenet of this view is that it is possible to use expansive monetary policy – money creation by the central bank (i.e. -

Brazil and the Alliance for Progress

BRAZIL AND THE ALLIANCE FOR PROGRESS: US-BRAZILIAN FINANCIAL RELATIONS DURING THE FORMULATION OF JOÃO GOULART‟S THREE-YEAR PLAN (1962)* Felipe Pereira Loureiro Assistant Professor at the Institute of International Relations, University of São Paulo (IRI-USP), Brazil [email protected] Presented for the panel “New Perspectives on Latin America‟s Cold War” at the FLACSO-ISA Joint International Conference, Buenos Aires, 23 to 25 July, 2014 ABSTRACT The paper aims to analyze US-Brazilian financial relations during the formulation of President João Goulart‟s Three-Year Plan (September to December 1962). Brazil was facing severe economic disequilibria in the early 1960s, such as a rising inflation and a balance of payments constrain. The Three-Year Plan sought to tackle these problems without compromising growth and through structural reforms. Although these were the guiding principles of the Alliance for Progress, President John F. Kennedy‟s economic aid program for Latin America, Washington did not offer assistance in adequate conditions and in a sufficient amount for Brazil. The paper argues the causes of the US attitude lay in the period of formulation of the Three-Year Plan, when President Goulart threatened to increase economic links with the Soviet bloc if Washington did not provide aid according to the country‟s needs. As a result, the US hardened its financial approach to entice a change in the political orientation of the Brazilian government. The US tough stand fostered the abandonment of the Three-Year Plan, opening the way for the crisis of Brazil‟s postwar democracy, and for a 21-year military regime in the country. -

Latin America Confronts the United States Asymmetry and Influence

4 A Recalculation of Interests NAFTA and Mexican Foreign Policy No event since the Mexican Revolution has had such a dramatic effect on relations between the United States and Mexico as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). NAFTA has often been understood as the result of expansionist U.S. trade policy at a triumphal historical moment – a victory for the U.S. international economic agenda even as the Soviet Union collapsed. This interpretation largely ignores Mexico’s role in initiating talks. NAFTA fed hopes for a “free trade zone stretching from the port of Anchorage to Tierra del Fuego,” in the words of President George H.W. Bush. 1 This initiative had started with Canada a few years prior. However, it received its most important boost when the United States and Mexico decided in early 1990 to pursue an agreement that would, for the first time, tightly link the world’s largest economy with that of a much lower-income country. Despite the congruence with announced U.S. policies – President Reagan had similarly dreamed of free trade from “Yukon to Yucatan” 2 – the pact hinged not on U.S. pressure but on Mexican leaders’ profound reevaluation of their own country’s interests. NAFTA reflected a realization that Mexico could best pursue its interests by engaging the United States in institutional arrangements instead of by rhetorical counters. Even before NAFTA, Mexico relied on exports of oil and light manufacturing from maquiladoras , over- whelmingly to the United States. The rules governing these exports were open to constant negotiations and the frequent threat of countervailing duties on Mexican products. -

The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America Volume Author/Editor: Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-15843-8 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/dorn91-1 Conference Date: May 18-19, 1990 Publication Date: January 1991 Chapter Title: The Macroeconomics of Populism Chapter Author: Rudiger Dornbusch, Sebastian Edwards Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8295 Chapter pages in book: (p. 7 - 13) 1 The Macroeconomics of Populism Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards Latin America’s economic history seems to repeat itself endlessly, following irregular and dramatic cycles. This sense of circularity is particularly striking with respect to the use of populist macroeconomic policies for distributive purposes. Again and again, and in country after country, policymakers have embraced economic programs that rely heavily on the use of expansive fiscal and credit policies and overvalued currency to accelerate growth and redistrib- ute income. In implementing these policies, there has usually been no concern for the existence of fiscal and foreign exchange constraints. After a short pe- riod of economic growth and recovery, bottlenecks develop provoking unsus- tainable macroeconomic pressures that, at the end, result in the plummeting of real wages and severe balance of payment difficulties. The final outcome of these experiments has generally been galloping inflation, crisis, and the col- lapse of the economic system. In the aftermath of these experiments there is no other alternative left but to implement, typically with the help of the Inter- national Monetary Fund (IMF), a drastically restrictive and costly stabiliza- tion program. -

The Rise of the New Money Doctors in Mexico Sarah Babb Department Of

The Rise of the New Money Doctors in Mexico Sarah Babb Department of Sociology The University of Massachusetts at Amherst [email protected] DRAFT ONLY: PLEASE DO NOT CITE WITHOUT AUTHOR’S PERMISSION Paper presented at a conference on the Financialization of the Global Economy, Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), University of Massachusetts at Amherst, December 7-8, 2001, Amherst, MA. Dr. E.W. Kemmerer, renowned Professor of Money and Banking and International Finance, did not lecture to a class of juniors and seniors in the fall of 1926 as originally scheduled. Instead, in mid- October, he, five other experts, two secretaries and four wives were aboard the British liner Ebro, off the northwest coast of South America. He wrote in his diary, 'We arrived in La Libertad, Ecuador, after dark...Took launch to Salinas, transferred to a smaller launch, then to a dug-out canoe and were finally carried ashore on the backs of natives.' --From Kemmerer, Donald L. 1992. The Life and Times of Professor Edwin Walter Kemmerer, 1875-1845, and How He Became an International "Money Doctor." Kemmerer, Donald L. P. 1. ASPE: In the 1950s, when Japan was labor-intensive, it was good that Japan had a current account deficit. Then Japan became highly capital-intensive and now has a surplus of capital. FORBES: This is getting complicated. ASPE: I'm sorry if I sound professorial. FORBES: Don't apologize. It's a pleasure to meet someone running an economy who understands economics. --From a Forbes magazine interview with former Mexican Finance Minister Pedro Aspe, entitled "We Don't Tax Capital Gains." Forbes. -

Capital Controls, Sudden Stops, and Current Account Reversals

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Capital Controls and Capital Flows in Emerging Economies: Policies, Practices and Consequences Volume Author/Editor: Sebastian Edwards, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-18497-8 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/edwa06-1 Conference Date: December 16-18, 2004 Publication Date: May 2007 Title: Capital Controls, Sudden Stops, and Current Account Reversals Author: Sebastian Edwards URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c0149 2 Capital Controls, Sudden Stops, and Current Account Reversals Sebastian Edwards 2.1 Introduction During the last few years a number of authors have argued that free cap- ital mobility produces macroeconomic instability and contributes to fi- nancial vulnerability in the emerging nations. For example, in his critique of the U.S. Treasury and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Stiglitz (2002) has argued that pressuring emerging and transition countries to re- lax controls on capital mobility during the 1990s was a huge mistake. Ac- cording to him, the easing of controls on capital mobility was at the center of most (if not all) currency crises in the emerging markets during the last decade—Mexico in 1994, East Asia in 1997, Russia in 1998, Brazil in 1999, Turkey in 2001, and Argentina in 2002. These days, even the IMF seems to criticize free capital mobility and to provide (at least some) support for capital controls. Indeed, on a visit to Malaysia in September 2003 Horst Koehler, then the IMF’s managing director, praised the policies of Prime Minister Mahathir, and in particular his use of capital controls in the after- math of the 1997 currency crisis (Beattie 2003). -

July-August 2017

July-August 2017 A Monthly Publication of the U.S. Consulate Krakow Volume VIII. Issue 5. President John F. Kennedy and his son, John Jr., 1963 (AP Photo) In this issue: President John F. Kennedy Zoom in on America The Life of John F. Kennedy John Fitzgerald Kennedy was born in Brookline, Massa- During WWII John applied and was accepted into the na- chusetts, on May 29, 1917 as the second of nine children vy, despite a history of poor health. He was commander of born into the family of Joseph Patrick Kennedy and Rose PT-100, which on August 2, 1943, was hit and sunk by a Fitzgerald Kennedy. John was often called “Jack”. The Japanese destroyer. Despite injuries to his back, an ail- Kennedys had a powerful impact on America. John Ken- ment that would haunt him to the end of his life, Kennedy nedy’s great-grandfather, Patrick Kennedy, emigrated managed to rescue his surviving crew members and was from Ireland to Boston in 1849 and worked as a barrel declared a “hero” by the New York Times. A year later Joe maker. His grandfather, Patrick Joseph (P.J.) Kennedy, was killed on a volunteer mission in Europe when his air- achieved success first in the saloon and liquor-import craft exploded. businesses, and then in banking. His father, Joseph Pat- Joseph Patrick now placed all his hopes on John. In 1946, rick Kennedy, made investments in banking, ship building, John F. Kennedy successfully ran for the same seat in real estate, liquor importing, and motion pictures and be- Congress, which his grandfather held nearly five decades came one of the richest men in America. -

Left Behind Latin America and the False Promise of Populism

Left Behind Latin America and the False Promise of Populism Sebastian Edwards THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS I CHICAGO AND LONDON Contents Preface xi 1 Latin America: The Eternal Land of the Future 1 • The Economic Future of Latin America and the United States • From the Washington Consensus to the Resurgence of Populism: A Brief Overview - The Main Argument: A Summary • A Conceptual Framework: The Economic Prosperity of -. Nations and the Mechanics of Successful Growth Transitions PART ONE A Long Decline: From Independence to the Washington Consensus 2 Latin America's Decline: A Long Historical View 21 • A Gradual and Persistent Decline j The Poverty of Institutions and Long-Term Mediocrity - Currency Crises, Instability, and Inflation - Inequality and Poverty - So Far from God, and So Close to the United States 3 From the Alliance for Progress to the Washington Consensus 47 • The Cuban Revolution and the Alliance for Progress • Protectionism and. Social Conditions ' Informality and Unemployment • Fiscal Profligacy, Monetary Largesse, Instability, and Currency Crises • - Oil Shocks and Debt Crisis • The Lost Decade, Market Reforms, and the Washington Consensus PART TWO The Washington Consensus and the Recurrence of Crises, 1989-2002 4 Fractured Liberalism: Latin Americas Incomplete Reforms 71 • Institutions and Economic Performance - Institutions Interrupted: A Latin American Scorecard - Economic Policy Reform: A Decalogue Manque * Summing Up: Mediocre Policies and Weak Institutions v __^ 5 Chile, Latin America's Brightest Star 101 * -

The Kennedy Administration's Alliance for Progress and the Burdens Of

The Kennedy Administration’s Alliance for Progress and the Burdens of the Marshall Plan Christopher Hickman Latin America is irrevocably committed to the quest for modernization.1 The Marshall Plan was, and the Alliance is, a joint enterprise undertaken by a group of nations with a common cultural heritage, a common opposition to communism and a strong community of interest in the specific goals of the program.2 History is more a storehouse of caveats than of patented remedies for the ills of mankind.3 The United States and its Marshall Plan (1948–1952), or European Recovery Program (ERP), helped create sturdy Cold War partners through the economic rebuilding of Europe. The Marshall Plan, even as mere symbol and sign of U.S. commitment, had a crucial role in re-vitalizing war-torn Europe and in capturing the allegiance of prospective allies. Instituting and carrying out the European recovery mea- sures involved, as Dean Acheson put it, “ac- tion in truly heroic mold.”4 The Marshall Plan quickly became, in every way, a paradigmatic “counter-force” George Kennan had requested in his influential July 1947 Foreign Affairs ar- President John F. Kennedy announces the ticle. Few historians would disagree with the Alliance for Progress on March 13, 1961. Christopher Hickman is a visiting assistant professor of history at the University of North Florida. I presented an earlier version of this paper at the 2008 Policy History Conference in St. Louis, Missouri. I appreciate the feedback of panel chair and panel commentator Robert McMahon of The Ohio State University. I also benefited from the kind financial assistance of the John F.