Paracelsus, the Five Matrices - and His Alchemy As a Ritual Field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Alchemical Journey Into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales

Studia Religiologica 51 (1) 2018, s. 33–45 doi:10.4467/20844077SR.18.003.9492 www.ejournals.eu/Studia-Religiologica Alchemical Journey into the Divine in Victorian Fairy Tales Emilia Wieliczko-Paprota https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8662-6490 Institute of Polish Language and Literature University of Gdańsk [email protected] Abstract This article demonstrates the importance of alchemical symbolism in Victorian fairy tales. Contrary to Jungian analysts who conceived alchemy as forgotten knowledge, this study shows the vivid tra- dition of alchemical symbolism in Victorian literature. This work takes the readers through the first stage of the alchemical opus reflected in fairy tale symbols, explains the psychological and spiritual purposes of alchemy and helps them to understand the Victorian visions of mystical transforma- tion. It emphasises the importance of spirituality in Victorian times and accounts for the similarity between Victorian and alchemical paths of transformation of the self. Keywords: fairy tales, mysticism, alchemy, subconsciousness, psyche Słowa kluczowe: bajki, mistyka, alchemia, podświadomość, psyche Victorian interest in alchemical science Nineteenth-century fantasy fiction derived its form from a different type of inspira- tion than modern fantasy fiction. As Michel Foucault accurately noted, regarding Flaubert’s imagination, nineteenth-century fantasy was more erudite than imagina- tive: “This domain of phantasms is no longer the night, the sleep of reason, or the uncertain void that stands before desire, but, on the contrary, wakefulness, untir- ing attention, zealous erudition, and constant vigilance.”1 Although, as we will see, Victorian fairy tales originate in the subconsciousness, the inspiration for symbolic 1 M. Foucault, Fantasia of the Library, [in:] Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, D.F. -

A Lexicon of Alchemy

A Lexicon of Alchemy by Martin Rulandus the Elder Translated by Arthur E. Waite John M. Watkins London 1893 / 1964 (250 Copies) A Lexicon of Alchemy or Alchemical Dictionary Containing a full and plain explanation of all obscure words, Hermetic subjects, and arcane phrases of Paracelsus. by Martin Rulandus Philosopher, Doctor, and Private Physician to the August Person of the Emperor. [With the Privilege of His majesty the Emperor for the space of ten years] By the care and expense of Zachariah Palthenus, Bookseller, in the Free Republic of Frankfurt. 1612 PREFACE To the Most Reverend and Most Serene Prince and Lord, The Lord Henry JULIUS, Bishop of Halberstadt, Duke of Brunswick, and Burgrave of Luna; His Lordship’s mos devout and humble servant wishes Health and Peace. In the deep considerations of the Hermetic and Paracelsian writings, that has well-nigh come to pass which of old overtook the Sons of Shem at the building of the Tower of Babel. For these, carried away by vainglory, with audacious foolhardiness to rear up a vast pile into heaven, so to secure unto themselves an immortal name, but, disordered by a confusion and multiplicity of barbarous tongues, were ingloriously forced. In like manner, the searchers of Hermetic works, deterred by the obscurity of the terms which are met with in so many places, and by the difficulty of interpreting the hieroglyphs, hold the most noble art in contempt; while others, desiring to penetrate by main force into the mysteries of the terms and subjects, endeavour to tear away the concealed truth from the folds of its coverings, but bestow all their trouble in vain, and have only the reward of the children of Shem for their incredible pain and labour. -

Ethan Allen Hitchcock Alchemy Collection in the St

A Guide to the Ethan Allen Hitchcock Alchemy Collection in the St. Louis Mercantile Library The St. Louis Mercantile Library Association Major-General Ethan Allen Hitchcock (1798 - 1870) A GUIDE TO THE ETHAN ALLEN HITCHCOCK COLLECTION OF THE ST. LOUIS MERCANTILE LIBRARY ASSOCIATION A collective effort produced by the NEH Project Staff of the St. Louis Mercantile Library Copyright (c) 1989 St. Louis Mercantile Library Association St. Louis, Missouri TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Staff................................ i Foreword and Acknowledgments................. 1 A Guide to the Ethan Allen Hitchcock Collection. .. 6 Aoppendix. 109 NEH PROJECT STAFF Project Director: John Neal Hoover* Archivist: Ann Morris, 1987-1989 Archivist: Betsy B. Stoll, 1989 Consultant: Louisa Bowen Typist: ' Betsy B. Stoll This project was made possible by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities * Charles F. Bryan, Jr. Ph.D., Executive Director of the Mercantile Library 1986-1988; Jerrold L. Brooks, Ph.D. Executive Director of the Mercantile Library, 1989; John Neal Hoover, MA, MLS, Acting Librarian, 1988, 1989, during the period funded by NEH as Project Director -i- FOREWORD & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: For over one thousand years, the field of alchemy gathered to it strands of religion, the occult, chemistry, pure sciences, astrology and magic into a broad general philosophical world view which was, quite apart from the stereotypical view of the charlatan gold maker, concerned with the forming of a basis of knowledge on all aspects of life's mysteries. As late as the early nineteenth century, when many of the modern fields of the true sciences of mind and matter were young and undeveloped, alchemy was a beacon for many people looking for a philosophical basis to the better understanding of life--to the basic religious and philosophical truths. -

The Paracelsians and the Chemists: the Chemical Dilemma in Renaissance Medicine

Clio Medica, Vol7, No.3, pp. 185-199, 1972 The Paracelsians and the Chemists: the Chemical Dilemma in Renaissance Medicine ALLEN G. DEBUS* Accounts of Renaissance iatrochemistry have traditionally emphasized the con flict over the introduction of chemically prepared medicines. The importance of this cannot be denied, but the texts of the period indicate that this formed only part of a broader debate involving the relationship of chemistry to medicine - and indeed, to nature as a whole. The Paracelsian chemists argued forcefully that much - if not all - of the fabric of ancient medicine should be scrapped, and that a new medicine based on a chemical philosophy of the universe should be offered in its place. For them a proper understanding of the macrocosm and the microcosm would indicate to the true physician the correct cures for diseases. Others - who spoke with no less conviction of the benefits of chemistry for medicine - disagreed with the Paracelsians over the application of chemistry to cosmological problems. For these chemists the introduction of the new remedies and the Paracelsian principles were useful and necessary for the physician, but they were properly to be used along with the traditional Aristotelian-Galenic conceptual scheme. The purpose of the present paper is to give some indication of the deep divisions that separated chemical physicians from each other in this crucial period. By way of background it should be noted that most chemical physicians of the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries did not consider their work to be entirely new. They openly drew upon the writings of Islamic physicians and alchemists as well as a host of Latin scholars of the Middle Ages who had turned to chemical operations as a basic tool for the preparation of medicines. -

John Dee, Willem Silvius, and the Diagrammatic Alchemy of the Monas Hieroglyphica

The Royal Typographer and the Alchemist: John Dee, Willem Silvius, and the Diagrammatic Alchemy of the Monas Hieroglyphica Stephen Clucas Birkbeck, University of London, UK Abstract: John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica (1564) was a work which involved a close collaboration between its author and his ‘singular friend’ the Antwerp printer Willem Silvius, in whose house Dee was living whilst he composed the work and saw it through the press. This article considers the reasons why Dee chose to collaborate with Silvius, and the importance of the intellectual culture – and the print trade – of the Low Countries to the development of Dee’s outlook. Dee’s Monas was probably the first alchemical work which focused exclusively on the diagrammatic representation of the alchemical process, combining diagrams, cosmological schemes and various forms of tabular grid. It is argued that in the Monas the boundaries between typography and alchemy are blurred as the diagrams ‘anatomizing’ his hieroglyphic sign (the ‘Monad’) are seen as revealing truths about alchemical substances and processes. Key words: diagram, print culture, typography, John Dee, Willem Silvius, alchemy. Why did John Dee go to Antwerp in 1564 in order to publish his recondite alchemical work, the Monas Hieroglyphica? What was it that made the Antwerp printer Willem Silvius a suitable candidate for his role as the ‘typographical parent’ of Dee’s work?1 In this paper I look at the role that Silvius played in the evolution of Dee’s most enigmatic work, and at the ways in which Silvius’s expertise in the reproduction of printed diagrams enabled Dee to make the Monas one of the first alchemical works to make systematic use of the diagram was a way of presenting information about the alchemical process. -

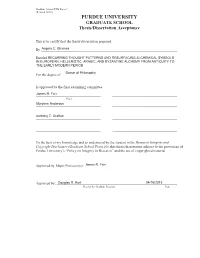

PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance

Graduate School ETD Form 9 (Revised 12/07) PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Angela C. Ghionea Entitled RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD Doctor of Philosophy For the degree of Is approved by the final examining committee: James R. Farr Chair Myrdene Anderson Anthony T. Grafton To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Research Integrity and Copyright Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 20), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy on Integrity in Research” and the use of copyrighted material. Approved by Major Professor(s): ____________________________________James R. Farr ____________________________________ Approved by: Douglas R. Hurt 04/16/2013 Head of the Graduate Program Date RECURRING THOUGHT PATTERNS AND RESURFACING ALCHEMICAL SYMBOLS IN EUROPEAN, HELLENISTIC, ARABIC, AND BYZANTINE ALCHEMY FROM ANTIQUITY TO THE EARLY MODERN PERIOD A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Angela Catalina Ghionea In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 Purdue University West Lafayette, Indiana UMI Number: 3591220 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3591220 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

Musaeum'hermeticum' Vol'i'

Musaeum'Hermeticum'_Vol'I' Musaeum'Hermeticum'_Vol'I' Musaeum'Hermeticum'_Vol'I' THE HERMETIC MUSEUM, RESTORED AND ENLARGED: MOST FAITHFULLY INSTRUCTING ALL DISCIPLES OF THE SOPHO-SPAGYRIC ART HOW THAT GREATEST AND TRUEST MEDICINE OF THE PHILOSOPHER'S STONE MAY BE FOUND AND HELD. NOW FIRST DONE INTO ENGLISH FROM THE LATIN ORIGINAL PUBLISHED AT FRANKFORT IN THE YEAR 1678. Translated by Arthur Edward Waite Containing Twenty-two most celebrated Chemical Tracts. London: J. Elliot and Co. [1893] Musaeum'Hermeticum'_Vol'I' p. vii PREFACE'TO'THE'ENGLISH'EDITION.' THE HERMETIC MUSEUM RESTORED AND ENLARGED was published in Latin at Frankfort, in the year 1678, and, as its title implies, it was an enlarged form of an anterior work which, appearing in 1625, is more scarce, but, intrinsically, of less value. Its design was apparently to supply in a compact form a representative collection of the more brief and less ancient alchemical writers; in this respect, it may be regarded as a supplement to those large storehouses of Hermetic learning such as the Theatrum Chemicum, and that scarcely less colossal of Mangetus, the Bibliotheca Chemica Curiosa, which are largely concerned with the cream of the archaic literature, with the works of Geber and the adepts of the school of Arabia, with the writings attributed to Hermes, with those of Raymond Lully, Arnold de Villa Nova, Bernard Trevisan, and others. THE HERMETIC MUSEUM would also seem to represent a distinctive school in Alchemy, not altogether committed to certain modes and terminology which derived most of their prestige from the past, and sufficiently enigmatical as it was, still inclined to be less obscure and misleading than was the p. -

What Painting Is “A Truly Original Book

More praise for What Painting Is “A truly original book. It will make you look at paintings differently and think about paint differently.”—Boston Globe “ This is a novel way of considering paintings, and excitingly different from standard art criticism.”—Atlantic Monthly “The best books often introduce new worlds. What Painting Is exposes the reader to painting materials, brushstroke techniques, and alchemy of all things, in a book filled with rich descriptions and illuminating insight. Read this and you’ll never look at paintings in the same way again.”— Columbus Dispatch “ James Elkins, his academic laces untied, traces a mysterious, evocation and an utterly convincing parallel between two spirits grounded in the earth—alchemy and painting. The author is an alchemist of ideas, and a painter. His openness to the love of quicksilver and sulfur, to putrefying animal excretions, and his expertise in imprimaturas, his feeling for the mysteries of the brushstroke —all of these allow him to concoct a heady elixir.” —Roald Hoffmann, Winner of the Noble Prize in Chemistry, 1981 What Painting Is How to Think about Oil Painting, Using the Language of Alchemy James Elkins Routledge New York • London Published in 2000 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE Copyright © 1999 by Routledge All rights reserved. -

Ge Hong's Master Who Embraces Simplicity (Baopuzi). In: Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident

Michael Puett Humans, Spirits, and Sages in Chinese Late Antiquity : Ge Hong's Master Who Embraces Simplicity (Baopuzi). In: Extrême-Orient, Extrême-Occident. 2007, N°29, pp. 95-119. Abstract This paper attempts to answer the questions : What was Ge Hong trying to do when he wrote the Baopuzi ? What were his arguments ? And why, within the context of the time, were these arguments significant ? In answering these questions, the essay claims that there is a unified set of ideas concerning humans, sages, and the spirit world in the Baopuzi. Moreover, it is a set of ideas that underlies both the inner and outer portions of the text. Michael Puett m^nMMtanammm.mi «##»*, «KHira, «h»a. mxu Résumé Hommes, esprits et sages dans l'Antiquité tardive : Le Maître qui embrasse la simplicité (Baopuzi) de Ge Hong Le présent article s'efforce de répondre à la question de savoir quelle pouvait être la visée de Ge Hong lorsqu'il composa le Baopuzi. Quelles idées y a-t-il avancées et comment les a-t-il défendues ? Enfin, qu'est- ce qui à la lumière de son époque donne à ses arguments un tour si particulier ? Nous soutenons dans ces pages qu'il y a une réelle cohérence argumentative et une vision d'ensemble dans le discours de Ge Hong sur les humains, les sages et les esprits. Cette ensemble d'idées innerve aussi bien les chapitres intérieurs qu'extérieurs de l'ouvrage. Citer ce document / Cite this document : Puett Michael. Humans, Spirits, and Sages in Chinese Late Antiquity : Ge Hong's Master Who Embraces Simplicity (Baopuzi). -

Magic, Mysticism, and Modern Medicine: the Influence of Alchemy on Seventeenth-Century England

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects History Department 4-2004 Magic, Mysticism, and Modern Medicine: The Influence of Alchemy on Seventeenth-Century England Lindsay Fitzharris '04 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Fitzharris '04, Lindsay, "Magic, Mysticism, and Modern Medicine: The Influence of Alchemy on Seventeenth-Century England" (2004). Honors Projects. 16. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj/16 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. • ILLINOIS WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY MAGIC, MYSTICISM, AND MODERN MEDICINE: THE INFLUENCE OF ALCHEMY ON SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLAND A THESIS PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY IN CANDIDACY FOR AN HONORS BACHELORS OF ARTS DEGREE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY LINDSAY A. FITZHARRIS BLOOMINGTON, ILLINOIS APRIL 2004 • [T]he historian of science can not devote much attention to the study of superstition and magic, that is, of unreason, because this does not help him very much to understand human progress. -

The Philosophers' Stone: Alchemical Imagination and the Soul's Logical

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 2014 The hiP losophers' Stone: Alchemical Imagination and the Soul's Logical Life Stanton Marlan Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Marlan, S. (2014). The hiP losophers' Stone: Alchemical Imagination and the Soul's Logical Life (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/874 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PHILOSOPHERS’ STONE: ALCHEMICAL IMAGINATION AND THE SOUL’S LOGICAL LIFE A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Stanton Marlan December 2014 Copyright by Stanton Marlan 2014 THE PHILOSOPHERS’ STONE: ALCHEMICAL IMAGINATION AND THE SOUL’S LOGICAL LIFE By Stanton Marlan Approved November 20, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Tom Rockmore, Ph.D. James Swindal, Ph.D. Distinguished Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy Emeritus (Committee Member) (Committee Chair) ________________________________ Edward Casey, Ph.D. Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at Stony Brook University (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ James Swindal, Ph.D. Ronald Polansky, Ph.D. Dean, The McAnulty College and Chair, Department of Philosophy Graduate School of Liberal Arts Professor of Philosophy Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT THE PHILOSOPHERS’ STONE: ALCHEMICAL IMAGINATION AND THE SOUL’S LOGICAL LIFE By Stanton Marlan December 2014 Dissertation supervised by Tom Rockmore, Ph.D.