Paul Valéry and the Poetics of Attention by Daniel Richard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technology, Language and Thought: Extensions of Meaning in the English Lexicon

2005:31 DOCTORAL T H E SI S Technology, Language and Thought: Extensions of Meaning in the English Lexicon Marlene Johansson Falck L L I M S Linguistics in the Midnight Sun Luleå University of Technology Department of Languages and Culture 2005:31|: 102-1544|: - -- 05⁄31 -- Marlene Johansson Falck Technology, Language, and Thought - Extensions of Meaning in the English Lexicon I Johansson Falck, Marlene (2005) Technology, Language and Thought – Extensions of Meaning in the English Lexicon. Doctoral dissertation no 2005:31. Department of Languages and Culture, Luleå University of Technology. Abstract In this thesis, the relationship between technological innovation and the development of language and thought is analysed. For this purpose, three different fields of technology are investigated: 1) the steam engine, 2) electricity, and 3) motor vehicles, roads and ways. They have all either played an extremely important part in people’s lives, or they are still essential to us. The overall aim is to find out in what ways these inventions and discoveries have helped people to develop abstract thinking and given speakers of English new possibilities to express themselves. Questions being asked are a) if the correlations in experience between the inventions and other domains have motivated new conceptual mappings? b) if the experiences that they provide people with may be used to re-experience certain conceptual mappings, and hence make them more deeply entrenched in people’s minds? and c) if the uses of them as cognitive tools have resulted in meaning extension in the English lexicon? The study is based on metaphoric and metonymic phrases collected from a number of different dictionaries. -

The Scopic Past and the Ethics of the Gaze

Ivan Illich Kreftingstr. 16 D - 28203 Bremen THE SCOPIC PAST AND THE ETHICS OF THE GAZE A plea for the historical study of ocular perception Filename and date: SCOPICPU.DOC Status: To be published in: Ivan Illich, Mirror II (working title). Copyright Ivan Illich. For further information please contact: Silja Samerski Albrechtstr.19 D - 28203 Bremen Tel: +49-(0)421-7947546 e-mail: [email protected] Ivan Illich: The Scpoic Past and the ethics of the Gaze 2 Ivan Illich THE SCOPIC PAST AND THE ETHICS OF THE GAZE A plea for the historical study of ocular perception1 We want to treat a perceptual activity as a historical subject. There are histories of the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, of the formation of a working class in Great Britain, of porridge in medieval Europe. We ourselves have explored the history of the experienced (female) body in the West. Now we wish to outline the domain for a history of the gaze - der Blick, le regard, opsis.2 The action of seeing is shaped differently in different epochs. We assume that the gaze can be a human act. Hence, our historical survey is carried out sub specie boni; we wish to explore the possibilities of seeing in the perspective of the good. In what ways is this action ethical? The question arose for us when we saw the necessity of defending the integrity and clarity of our senses - our sense experience - against the insistent encroachments of multimedia from cyberspace. From our backgrounds in history, we felt that we had to resist the dissolution of the past by seemingly sophisticated postmodern catch phrases, for example, the deconstruction of conversation into a process of communication. -

Catalogue-Assunta-Cassa-English.Pdf

ASSUNTA CASSA 1st edition - June 2017 graphics: Giuseppe Bacci / Daniele Primavera photography: Emanuele Santori translations: Angela Arnone printed by Fastedit - Acquaviva Picena (AP) e-mail: [email protected] website: www.assuntacassa.it Assunta Cassa beyond the horizon edited by Giuseppe Bacci foreward by Giuseppe Marrone critical texts by Rossella Frollà, Anna Soricaro, Giuseppe Bacci 4 - Assunta Cassa - Beyond the horizon The Quest of Assunta Cassa for Delight and Dynamic Beauty Giuseppe Marrone Sensuality, movement, technique whose gesture, form and that rears up when least expected, reaching the apex and trac- matter are scented with the carnal thrill of dance it conveys, ing out perceptual geometries that perhaps no one thought compelling it on the eye, calling out to it and enticing the viewer, could be experimented. the recipient of the work who is dazed by an emotion stronger The art of Assunta Cassa has something primal in its emotional than delighted connection, and feels the inner turmoil triggered factor, no one should miss the thrill of experiencing her works by the virtuous explosions of colour and matter. The subject, in person, absorbing some of that passion, which enters the the dance, the movement, the steps that shift continuous exist- mind first and then sinks deeper into the spheres of perception. ence, igniting a split second and fixing it forever on the canvas. Sensuality and love, tenderness and passion, move with and Dynamic eroticism, rising yet immobile, fast, uncontrollable in in the dancing figures, which surprise with their natural seeking mind and in passion, able to erupt in a flash and unleash the of pleasure in the gesture, the beauty of producing a human fiercest emotion, the sheer giddiness of the most intense per- movement, again with sheer spontaneity, finding the refined ception. -

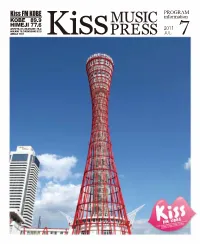

Musicpress.Pdf

スルッとスキニー&億千米 サンプルセットプレゼント中!! Kiss FM KOBE Event Report あ の『 億 千 米 』が パ ウ ダ ー タ イ プ に な っ て 新 登 場 ! ! 2011.6.4 sat @KOBE 植物性乳酸菌で女性の悩みをサポート 6月4日土曜日。週末の三宮の一角、イル・アルバータ神戸の前には鮮やか な黄色の[yellow tail]のフラッグが立ち並んでいた。そこに訪れるのは、 Kiss FMのイベント応募で選ばれた15組30名のワイン好きキスナー達。 店内に入ると、まず目に入るのは入り口近くに置かれた大きなグラス。しか もこちらには、オレンジジュース10Lに赤ワイン16本を注いだという、な んと本物のカクテルが。向かいのバーカウンター横には、セルフでカクテル を作れるスペースも設置されており、自分好みの味を楽しめるようになっ ている。イベントのMCを務めるのは、ワイン好きとしても知られるサウン ド ク ル ー ・ R I B E K A 。こ の 日 の コ ン セ プ ト“ ワ イ ン を 気 軽 に 楽 し む ”た め に 用意されたオリジナルカクテルが紹介される。 グレープフルーツを合わせ、酸味とその美しい青色が見た目にも爽やかな ブルーバブルス。イチゴとオレンジの香りにヨーグルト、 薄いピンク色が女性にも喜ばれそうなピンクテイル。カ シスとコーラによってジュースのように飲みやすいレッド テイル。そんなワインカクテルにぴったりな、イル・アル バータ特製の料理も次々と運ばれ、参加者達は舌鼓を打 お米の乳酸菌を、発酵技術で増やしました。 ちつつワインをゆったりと楽しんだ。 玄米食が苦手な人も思わずにっこりの美味しさです。 この日スペシャルトークゲストとして登場したのはmihimaru GTの 二人。告知なしで目の前に現れたシークレットアーティストに、会場 の歓声が上がる。芦屋出身で、神戸もよく訪れていたというヴォーカ ルhiroko。テーブルに置かれた3種類のカクテルを飲みながら「めっ ち ゃ 美 味 し い ! 」と 関 西 弁 で 嬉 し そ う に 微 笑 ん だ 。R I B E K A が「 ガ ン ガン飲んではるんですけど」と笑う通り、「美味しくて全部飲み干し たい!」と観客を和ませる良い飲みっぷりを披露。新曲『マスターピー Kiss MUSIC PRESS読者限定 ス』の作成秘話や、ソロ活動を経てこれからのmihimaru GTについ てカクテルpartyならではの親しみある雰囲気で語ってくれた。 サ ン プル セットプレ ゼ ント !! 次に登場したのは、ライブゲストのザッハトルテ。ジャズを中心と 下記よりご応募いただいた皆様の中から『スルッとスキ し た 多 ジ ャン ル の 楽 曲 を ア コ ー デ ィ オ ン・ギ タ ー・チ ェ ロ と い う 変 ニー!』3gスティック×5本と億千米25g×2袋を 則的にも思える構成で演奏する彼らだけあって、それぞれの髪型 セットにして300名様にプレゼントいたします! も か な り 個 性 的 。し か し 、一 音 鳴 ら せ ば「 窓 の 外 に 見 え る 三 宮 の 景 色 が 、ま る で パ リ の 街 並 み 」と R I B E K A も 語 る よ う に 、独 特 の 空 気 ■応募方法 感がその場にいる人々の前に作り出される。『素敵な1日』や『それ Kiss FM KOBEのサイトトップページ右側にあるプレゼント パソコン 欄から『スルッとスキニー!&億千米 サンプルセット』を選択、 で も セ ー ヌ は 流 れ る 』な -

The Divine Alchemy of J. R. R. Tolkien's the Silmarillion David C

The Divine Alchemy of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion David C. Priester, Jr. Gray, GA B.A., English and Philosophy, Vanderbilt University, 2017 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia May, 2020 Abstract J. R. R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion demonstrates a philosophy of creative imagination that is expressed in argumentative form in Tolkien’s essay “On Fairy Stories.” Fully appreciating the imaginative architecture of Tolkien’s fantastic cosmos requires considering his creative work in literary and theological dimensions simultaneously. Creative writing becomes a kind of spiritual activity through which the mind participates in a spiritual or theological order of reality. Through archetypal patterns Tolkien’s fantasy expresses particular ways of encountering divine presence in the world. The imagination serves as a faculty of spiritual perception. Tolkien’s creative ethic resonates with the theological aesthetics of Hans Urs von Balthasar, a consideration of which helps to illuminate the relationship of theology and imaginative literature in The Silmarillion. Creative endeavors may be seen as analogous to the works of alchemists pursuing the philosopher’s stone through the transfiguration of matter. The Silmarils symbolize the ideal fruits of creative activity and are analogous to the philosopher’s stone. Priester 1 The Divine Alchemy of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Silmarillion Where shall we begin our study of J. R. R. Tolkien’s Silmarillion? The beginning seems like a very good place to start: “There was Eru, the One, who in Arda is called Ilúvatar; and he made first the Ainur, the Holy Ones, that were the offspring of his thought” (3). -

The Eye in the Torah: Ocular Desire in Midrashic Hermeneutic Author(S): Daniel Boyarin Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol

The Eye in the Torah: Ocular Desire in Midrashic Hermeneutic Author(s): Daniel Boyarin Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Spring, 1990), pp. 532-550 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1343638 Accessed: 09/02/2010 04:26 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org The Eye in the Torah: Ocular Desire in Midrashic Hermeneutic Daniel Boyarin It seems to have become a commonplace of critical discourse that Juda- ism is the religion in which God is heard but not seen. -

Copyright © 2007 Peter Beck All Rights Reserved. the Southern Baptist

Copyright © 2007 Peter Beck All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. THE VOICE OF FAITH: JONATHAN EDWARDS'S THEOLOGY OF PRAYER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Peter Beck December 2007 UMI Number: 3300625 Copyright 2007 by Beck, Peter All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3300625 Copyright 2008 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 APPROVAL SHEET THE VOIGE OF FAITH: JONATHAN EDWARDS'S THEOLOGY OF PRAYER Peter Beck Read and Approved by: Chad O. Brand To Melanie, my best friend and love, and to Alex and Karis, living proof of God's blessings on our home TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE . Vll Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................ 1 The "Great Duty" .... -

February 202020162016

Covering Main Street and Beyond. VOLUMEVOLUME 5. 1. HURLEYVILLE,HURLEYVILLE, SULLIVAN SULLIVAN COUNTY, COUNTY, N.Y. N.Y. | DECEMBER| FEBRUARY 2016 2020 NUMBERNUMBER 7. 2. BETTERBASKETBALL TO LOVE NO HOME FOR HATE by Adele Berger tor Martin Niemoller, who spent seven years in a con- MONTICELLO – On a centration camp after hav- cold Sunday afternoon of ing turned a blind eye early January 19, a group of con- on while the Nazis took cerned citizens gathered control of Germany. on the steps of the Sullivan “It’s too late to recite County Courthouse to raise that,” Mr. Colavito contin- their voices and stand up ued, “It’s too late, because against hate crimes. we are already there.” Simply titled, “Hate Has The crowd nodded in No Home in Sullivan Coun- agreement. ty,” the group of citizens that Even though the turnout gathered on the steps that af- was small, the overwhelm- ternoon represented a grow- ing sentiment was that hate ing sense of dread for some and intolerance, whether ethnic groups in the area based on race, ethnicity, reli- as more instances of hate gious affiliations, or gender, crimes, involving the Jew- were not going to be taken ish, Muslim and Black com- lightly in Sullivan County. munities have become more Mr. Encarnacion spoke common in this country. At- about “different strokes for tacks, such as the one that different folks” but noted occurred at a Hanukah cele- that all faiths shared a vision bration in Monsey, have sent to help our fellow brother. a ripple of anxiety through a “Remember,” he said. -

San José Studies, Fall 1993

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks San José Studies, 1990s San José Studies Fall 10-1-1993 San José Studies, Fall 1993 San José State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_90s Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation San José State University Foundation, "San José Studies, Fall 1993" (1993). San José Studies, 1990s. 12. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_90s/12 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the San José Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in San José Studies, 1990s by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sa~e p64i Ste«tie4 Volume XIX, Number 3 Fall, 1993 EDITORS John Engell, English, San Jose State University D. Mesher, English, San Jose State University EMERITUS EDITOR Fauneil J. Rinn, Political Science, San Jose State University ASSOCIATE EDITORS Susan Shillinglaw, English, San Jose State University William Wiegand, Emeritus, Creative Writing, San Francisco State Kirby Wilson, Creative Writing, Cabrillo College EDITORIAL BOARD Garland E. Allen, Biology, Washington University Judith P. Breen, English, San Francisco State University Hobart W. Bums, Philosophy, San Jose State University Robert Casillo, English, ·university ofMiami, Coral Gables Richard Flanagan, Creative Writing, Babson College Barbara Charlesworth Gelpi, English, Stanford University Robert C. Gordon, English and Humanities, San Jose State University Richard E. Keady, Religious Studies, San Jose State University Jack Kurzweil, Electrical Engineering, San Jose State University Hank Lazer, English, University ofAlabama Lela A. Llorens, Occupational Therapy, San Jose State University Lois Palken Rudnik, American Studies, University ofMassachusetts, Boston Richard A. -

Secret of the Ages by Robert Collier

Secret of the Ages Robert Collier This book is in Public Domain and brought to you by Center for Spiritual Living, Asheville 2 Science of Mind Way, Asheville, NC 28806 828-253-2325, www.cslasheville.org For more free books, audio and video recordings, please go to our website at www.cslasheville.org www.cslasheville.org 1 SECRET of THE AGES ROBERT COLLIER ROBERT COLLIER, Publisher 599 Fifth Avenue New York Copyright, 1926 ROBERT COLLIER Originally copyrighted, 1925, under the title “The Book of Life” www.cslasheville.org 2 Contents VOLUME ONE I The World’s Greatest Discovery In the Beginning The Purpose of Existence The “Open Sesame!” of Life II The Genie-of-Your-Mind The Conscious Mind The Subconscious Mind The Universal Mind VOLUME TWO III The Primal Cause Matter — Dream or Reality? The Philosopher’s Charm The Kingdom of Heaven “To Him That Hath”— “To the Manner Born” IV www.cslasheville.org 3 Desire — The First Law of Gain The Magic Secret “The Soul’s Sincere Desire” VOLUME THREE V Aladdin & Company VI See Yourself Doing It VII “As a Man Thinketh” VIII The Law of Supply The World Belongs to You “Wanted” VOLUME FOUR IX The Formula of Success The Talisman of Napoleon “It Couldn’t Be Done” X “This Freedom” www.cslasheville.org 4 The Only Power XI The Law of Attraction A Blank Check XII The Three Requisites XIII That Old Witch—Bad Luck He Whom a Dream Hath Possessed The Bars of Fate Exercise VOLUME FIVE XIV Your Needs Are Met The Ark of the Covenant The Science of Thought XV The Master of Your Fate The Acre of Diamonds XVI Unappropriated -

THE ART of CARLOS KLEIBER Carolyn Watson Thesis Submitted In

GESTURE AS COMMUNICATION: THE ART OF CARLOS KLEIBER Carolyn Watson Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney May 2012 Statement of Originality I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Signed: Carolyn Watson Date: ii Abstract This thesis focuses on the art of orchestral conducting and in particular, the gestural language used by conductors. Aspects such as body posture and movement, eye contact, facial expressions and manual conducting gestures will be considered. These nonverbal forms of expression are the means a conductor uses to communicate with players. Manual conducting gestures are used to show fundamental technical information relating to tempo, dynamics and cues, as well as demonstrating to a degree, musical expression and conveying an interpretation of the musical work. Body posture can communicate authority, leadership, confidence and inspiration. Furthermore, physical gestures such as facial expressions can express a conductor’s mood and demeanour, as well as the emotional content of the music. Orchestral conducting is thus a complex and multifarious art, at the core of which is gesture. These physical facets of conducting will be examined by way of a case study. The conductor chosen as the centrepiece of this study is Austrian conductor, Carlos Kleiber (1930-2004). Hailed by many as the greatest conductor of all time1, Kleiber was a perfectionist with unscrupulously high standards who enjoyed a career with some of the world’s finest orchestras and opera companies including the Vienna Philharmonic, La Scala, Covent Garden, the Met and the Chicago Symphony. -

Casiopea Discography1979 2009Rar

Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar 1 / 3 2 / 3 Download. Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar. casiopea....(1979)....super....flight....(1979)....ean;....ean....4542696000064:........casiopea.........2009........527.. Desde 1979, já gravaram 39 discos. ... Em janeiro de 2009, Casiopea estava envolvida com um álbum, "Tetsudou Seminar Ongakuhen", com .... SLT Reverse Directory 2012.rar > http://urlin.us/0f668 972c82176d ttl model handbra trio checked. Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar. 4578810581,,,19,, .... The Cure - Discography (114 albums) 1979 to 2009).rar (84.46 KB) Choose free or premium download FREE REGISTERED. Issei Noro and .... SLT Reverse Directory 2012.rar > http://urlin.us/0f668 972c82176d ttl model handbra trio checked. Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar. Artist: Casiopea Title Of Album: Discography Year Release: 1979-2009 ... torrent, mediafire, dvdrip, serial crack keygen,Casiopea rapidshare, .... Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar > tinyurl.com/pq9ykhq.. CASIOPEA MINT SESSION (With Tetsuo Sakurai & Akira Jimbo). (2DVD) .. Casiopea, also known as Casiopea 3rd is a Japanese jazz fusion band formed in 1976 by ... They recorded their debut album Casiopea (1979) with guest appearances by ... In January 2009, Casiopea participated in the album Tetsudou Seminar Ongakuhen, based on Minoru Mukaiya's Train Simulator video games.. Showing posts with label Casiopea Discography. ... Casiopea - Discography (63CD) 1979-2009 MP3 MP3 VBR, 192-320 kbps | Jazz, Fusion | 63CD | 8.1GB .... https://murodoclassicrock4.blogspot.com/2016/03/casiopea- ... with most, if not all, their discography from 1979 to 2009, mostly in 320kbps.. Download. Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar. casiopea. ... (1993-1997)Albums:Casiopea..-..Casiopea.. Pat Benatar - Discography (23 .... Casiopea Discography(1979 2009).rar casiopea discography, casiopea discography download, casiopea discography blogspot, casiopea ...