The State. the Fate of a Concept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Collected Works of Ananda K Coomaraswamy Series

A. Collected Works of Ananda K. Coomaraswamy Philosophical Writings TIME AND ETERNITY Ananda K.Coomaraswamy 1990, viii+107 pp. bib., ref., index ISBN: 81-85503-00-1: Rs 110 (HB) Man's awareness of Time has been articulated in ancient and modern civilizations through cosmologies, metaphysics, philosophy, religion, theology and the arts. Coomaraswamy propounds that though we live in Time, our deliverance lies in eternity. All religions make this distinction between what is merely "everlasting" (or "perpetual") and what is eternal. To probe into this mystery Coomaraswamy provides us with a detailed account of the teachings of each of the main world religions. Present edition embodies all marginal corrections which Coomaraswamy made on the first edition published during 1947 in Ascona, Switzerland. SPIRITUAL AUTHORITY AND TEMPORAL POWER IN THE INDIAN THEORY OF GOVERNMENT Ananda K.Coomaraswamy Edited by Keshavram N. Iyengar and Rama P.Coomaraswamy 1993, x+127pp. notes., ref., ISBN: 0-19-5631-43-9: Rs 200 (HB) 2013, xii+135pp., ISBN 13 : 978-81-246-0734-3 RsÊ.360 (HB) (reprint). The Indian theory of government is expounded in this work on the basis of the textual sources, mainly of the Brāhmaṇas and te Ṛgveda. The mantra from the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa (VIII.27) by which the priest addresses the king, spells out the relation between the spiritual and the temporal power. This "marriage formula" has its analogous applications in the cosmic, political, family and individual spheres of operation, in each by the conjunction of complementary agencies. The welfare of the community in each case depends upon a succession of obediences and loyalties; that of the subjects to the dual control of king and priest, that of the king to the priest, and that of all to the principle of an eternal law (dharma) as king of kings. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

European Imperialism

Quotes Basics Science History Social Other Search h o m e e u r o p e a n i m p e r i a l i s m c o n t e n t s Hinduism remains a vibrant, cultural and religious force in the world today. To understand Hinduism, it is necessary that we examine its history and marvel at its sheer stamina to survive in spite of repeated attacks across India's borders, time and again, by Greeks, Shaks, Huns, Arabs, Pathans, Mongols, Portuguese, British etc. India gave shelter, acceptance, and freedom to all. But, in holy frenzy, millions of Hindus were slaughtered or proselytized. Their cities were pillaged and burnt, temples were destroyed and accumulated treasures of centuries carried off. Even under grievous persecutions from the ruling foreigners, the basics of its civilization remained undefiled and, as soon as the crises were over Hindus returned to the same old ways of searching for the perfection or the unknown. Introduction The history of what is now India stretches back thousands of years, further than that of nearly any other region on earth. Yet, most historical work on India concentrates on the period after the arrival of Europeans, with predictable biases, distortions, and misapprehensions. Many overviews of Indian history offer a few cursory opening chapters that take the reader from Mohenjo-daro to the arrival of the Moghuls and the Europeans. India's history is ancient and abundant. The profligacy of monuments so testifies it and so does a once-lost civilization, the Harappan in the Indus valley, not to mention the annals commissioned by various conquerors. -

ICME Newsletter 41, September 2005 Contents: 1. WORDS from THE

ICME Newsletter 41, September 2005 Contents: 1. WORDS FROM THE PRESIDENT - INCLUSION IN DIVERSITY 2. ICME2005. CAN ORAL HISTORY MAKE OBJECTS SPEAK? CONFERENCE UPDATE 3. A LETTER FROM PROF. PH.D CORNELIU BUCUR. DIRECTOR GENERAL ASTRA MUSEUM 4. REGIONAL COLLOQUIUM: 'DO MUSEUMS STILL MATTER? MAKING THE CASE, FINDING THE WAYS' - LIDIJA NIKOCEVIC 5. MUSEUMS AND THE ROMA DECADE - BEATE WILDE 6. 7. UP-COMING CONFERENCES AND EVENTS 8. WORDS FROM THE EDITOR 1. WORDS FROM THE PRESIDENT - INCLUSION IN DIVERSITY It will only be a month before I see many of you at the 2005 ICME conference in Nafplion. I'm looking forward to that. However, with an official voting membership of nearly 300 spread around the world, and close to 700 email addresses on our ICME newsgroup, there will be many more of you who I WON'T see there than I will. That only a portion of ICME members attend any one conference is normal - for ICME as well as for most other ICOM international committees. As far as I know, we have never had more than 100 participants during any one ICME meeting since our founding in 1946. ICME conferences tend therefore to be fairly intimate affairs. This intimacy is unfortunately partly due to the high cost of international travel, as belied by the many emails I recieve from collegues who tell me they would like to attend, but have problems obtaining adequate funding to cover the expenses. Could another reason for intimate ICME conferences be a feeling that the conference themes are not useful for one's own work? Or perhaps that there are so many other tasks to complete, and it is difficult to find time to leave one's job? Or that the conference will be held in a language which is difficult to follow? A recent discussion on the ICOM-L list highlights the above problems. -

COLOMBIA on the PATH to a KNOWLEDGE-BASED SOCIETY Reflections and Proposals Volumen 1 E O Urib

COLOMBIA ON THE PATH TO A KNOWLEDGE-BASED SOCIETY Reflections and proposals Volumen 1 e o Urib ederic COLOMBIA - 2019 Artista: F COLOMBIA ON THE PATH TO A KNOWLEDGE-BASED SOCIETY Reflections and proposals Volume 1 © Vicepresidencia de la República de Colombia © Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación First edition, 2020 Printed ISBN: 978-958-5135-22-2 Digital ISBN: 978-958-5135-23-9 Printed ISBN (Spanish version): 978-958-5135-12-3 Digital ISBN (Spanish version): 978-958-5135-13-0 Collection Misión Internacional de Sabios 2019 Editors Clemente Forero Pineda Moisés Wasserman Tim Andreas Osswald Translator Tiziana Laudato Collection design and cover leonardofernandezsuarez.com Layout Leonardo Fernández Suárez Selva Estudio SAS Bogotá, D. C., Colombia, 2020 COLOMBIA ON THE PATH TO A KNOWLEDGE-BASED SOCIETY Reflections and proposals Volume 1 COMMISSIONERS Biotechnology, Bioeconomy Sustainable Energy and the Environment Juan Benavides Estévez-Bretón, Silvia Restrepo, coordinator coordinator Cristian Samper Angela Wilkinson (United Kingdom) Federica di Palma (United Kingdom) Eduardo Posada Flórez Elizabeth Hodson José Fernando Isaza Mabel Torres Creative and Cultural Industries Esteban Manrique Reol (Spain) Edgar Puentes, coordinator Michel Eddi (France) Ramiro Osorio Ludger Wessjohann (Germany) Camila Loboguerrero Germán Poveda Jaramillo Lina Paola Rodríguez Fernández Basic and Space Sciences Carlos Jacanamijoy Moisés Wasserman Lerner, coordinator Alfredo Zolezzi (Chile) Carmenza Duque Beltrán Oceans and Water Resources Serge Haroche -

The Mountain Path

THE MOUNTAIN PATH Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of those who meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala! Fearless I seek Thee, Fearlessness Itself! How canst Thou fear to take me, O Arunachala ? (A QUARTERLY) — Th$ Marital Garland " Arunachala ! Thou dost root out the ego of those who of Letters, verse 67 meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala! " — The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1. Publisher : T. N. Venkataraman, President, Board of Trustees, Vol. 17 JULY 1980 No. Ill Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai. * CONTENTS Page Editorial Board : EDITORIAL: The Journey Inward .. 127 Prof. K. Swaminathan The Nature and Function of the Guru Sri K. K. Nambiar —Arthur Osborne .. 129 Mrs. Lucy Cornelssen Bhagavan's Father .. 134 Smt. Shanta Rungachary Beyond Thought — Dr. K. S. Rangappa .. 136 Dr. K. Subrahmanian Mind and Ego — Dr. M. Sadashiva Rao .. 141 Sri Jim Grant Suri Nagamma — Joan Greenblatt .. 144 Sri David Godman A Deeply Effective Darshan of Bhagavan — /. D. M. Stuart and O. Raumer-Despeigne .. 146 God and His Names — K. Subrahmanian .. 149 Religions or Philosophy? — K. Ramakrishna Rao . 150 Managing Editor: The Way to the Real — A. T. Millar .. 153 V. Ganesan, Song of At-One-Ment — (IV) Sri Ramanasramam, — K. Forrer .. 155 Tiruvannamalai Scenes from Ramana's Life — (III) — B. V. Narasimha Swamy .. 159 * Transfiguration — Mary Casey .. 162 Garland of Guru's Sayings — Sri Muruganar Annual Subscription Tr. by Professor K. Swaminathan .. 163 INDIA Rs. 10 Reintegration, Part II, Awareness — Wei Wu Wei 165 FOREIGN £ 2.00 $ 4.00 Ramana Maharshi and How not to Grow Life Subscription : Old — Douglas Harding . -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMi films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 ® Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. “II n’y a pas de ‘potentially hot issues’?” Paradoxes of Displaying Arab-Canadian Lands within the Canadian Museum of Civilization Following 9.11 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Institute of Political Economy Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada By Elayne Oliphant April 2005 © Elayne Oliphant Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Dr Moira Simpson Museum Consultant and Art Educator Specialising in Ethnomuseology, Cultural Diversity, & Visual Arts

Dr Moira Simpson Museum Consultant and Art Educator specialising in Ethnomuseology, Cultural Diversity, & Visual Arts Celebrating Diversity Illustrated Presentations, Lectures, Seminars and Workshops Topics can be adapted for a range of audiences including: Special interest groups such as art societies and guilds; Staff of museums, art galleries and heritage organizations, Under-graduate and post-graduate students of Museum Studies, Heritage Studies, Tourism, Archaeology, Anthropology, and Arts Education; Pre-service and in-service teachers; Primary and secondary students. Please contact me to discuss your requirements. Dr Moira Simpson E-vocative Consulting Phone: (08) 8388 2371 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.e-vocative.com Museology, Heritage, and Non-Western Visual Arts Museum Learning Illustrated presentations Illustrated presentations for Staff of Museums & Arts of Aboriginal Australia: Tradition & Change Art Galleries, Academics & Students Bark Painting of Arnhem Land Museums & Multiculturalism Aboriginal Art of the Australian Desert Region Museums & Indigenous Peoples in Post-colonial History & Politics in Aboriginal Australia Art Contexts: Confrontations & Collaborations Maori Art: Tradition & Change Museum Collections: Questions of Ownership, Custodianship & Repatriation History & Politics in Native North American Art Ethnomuseology: Culturally-appropriate Display, Ravens, Eagles, Thunderbirds & Sea Wolves: Conservation & Interpretation Indian Art of the NW Coast of North America Protecting the Sacred: Concealment -

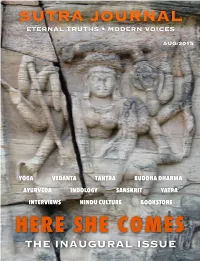

The Inaugural Issue Sutra Journal • Aug/2015 • Issue 1

SUTRA JOURNAL ETERNAL TRUTHS • MODERN VOICES AUG/2015 YOGA VEDANTA TANTRA BUDDHA DHARMA AYURVEDA INDOLOGY SANSKRIT YATRA INTERVIEWS HINDU CULTURE BOOKSTORE HERE SHE COMES THE INAUGURAL ISSUE SUTRA JOURNAL • AUG/2015 • ISSUE 1 Invocation 2 Editorial 3 What is Dharma? Pankaj Seth 9 Fritjof Capra and the Dharmic worldview Aravindan Neelakandan 15 Vedanta is self study Chris Almond 32 Yoga and four aims of life Pankaj Seth 37 The Gita and me Phil Goldberg 41 Interview: Anneke Lucas - Liberation Prison Yoga 45 Mantra: Sthaneshwar Timalsina 56 Yatra: India and the sacred • multimedia presentation 67 If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him Vikram Zutshi 69 Buddha: Nibbana Sutta 78 Who is a Hindu? Jeffery D. Long 79 An introduction to the Yoga Vasistha Mary Hicks 90 Sankalpa Molly Birkholm 97 Developing a continuity of practice Virochana Khalsa 101 In appreciation of the Gita Jeffery D. Long 109 The role of devotion in yoga Bill Francis Barry 113 Road to Dharma Brandon Fulbrook 120 Ayurveda: The list of foremost things 125 Critics corner: Yoga as the colonized subject Sri Louise 129 Meditation: When the thunderbolt strikes Kathleen Reynolds 137 Devata: What is deity worship? 141 Ganesha 143 1 All rights reserved INVOCATION O LIGHT, ILLUMINATE ME RG VEDA Tree shrine at Vijaynagar EDITORIAL Welcome to the inaugural issue of Sutra Journal, a free, monthly online magazine with a Dharmic focus, fea- turing articles on Yoga, Vedanta, Tantra, Buddhism, Ayurveda, and Indology. Yoga arose and exists within the Dharma, which is a set of timeless teachings, holistic in nature, covering the gamut from the worldly to the metaphysical, from science to art to ritual, incorporating Vedanta, Tantra, Bud- dhism, Ayurveda, and other dimensions of what has been brought forward by the Indian civilization. -

By Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

From the World Wisdom online library: www.worldwisdom.com/public/library/default.aspx THE VEDANTA AND WESTERN TRADITION* Ananda Coomaraswamy These are really the thoughts of all men in all ages and lands, they are not original with me. Walt Whitman I There have been teachers such as Orpheus, Hermes, Buddha, Lao tzu, and Christ, the historicity of whose human existence is doubtful, and to whom there may be accorded the higher dignity of a mythical reality. Shankara, like Plotinus, Augustine, or Eckhart, was certainly a man among men, though we know comparatively little about his life. He was of south Indian Brahman birth, flourished in the first half of the ninth century A.D., and founded a monastic order which still survives. He became a samnyasin, or “truly poor man,” at the age of eight, as the disciple of a certain Govinda and of Govinda’s own teacher Gaudapada, the author of a treatise on the Upanisads in which their essential doctrine of the non-duality of the divine Being was set forth. Shankara journeyed to Benares and wrote the famous commentary on the Brahma Sutra there in his twelfth year; the commentaries on the Upanisads and Bhagavad Gita were written later. Most of the great sage’s life was spent wandering about India, teaching and taking part in controversies. He is understood to have died between the ages of thirty and forty. Such wanderings and disputations as his have always been characteristically Indian institutions; in his days, as now, Sanskrit was the lingua franca of learned men, just as for centuries Latin was the lingua franca of Western countries, and free public debate was so generally recognized that halls erected for the accommodation of peri patetic teachers and disputants were at almost every court. -

Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow

The Matheson Trust Sankara's Doctrine of Maya Harry Oldmeadow Published in Asian Philosophy (Nottingham) 2:2, 1992 Abstract Like all monisms Vedanta posits a distinction between the relatively and the absolutely Real, and a theory of illusion to explain their paradoxical relationship. Sankara's resolution of the problem emerges from his discourse on the nature of maya which mediates the relationship of the world of empirical, manifold phenomena and the one Reality of Brahman. Their apparent separation is an illusory fissure deriving from ignorance and maintained by 'superimposition'. Maya, enigmatic from the relative viewpoint, is not inexplicable but only not self-explanatory. Sankara's exposition is in harmony with sapiential doctrines from other religious traditions and implies a profound spiritual therapy. * Maya is most strange. Her nature is inexplicable. (Sankara)i Brahman is real; the world is an illusory appearance; the so-called soul is Brahman itself, and no other. (Sankara)ii I The doctrine of maya occupies a pivotal position in Sankara's metaphysics. Before focusing on this doctrine it will perhaps be helpful to make clear Sankara's purposes in elaborating the Advaita Vedanta. Some of the misconceptions which have afflicted English commentaries on Sankara will thus be banished before they can cause any further mischief. Firstly, Sankara should not be understood or approached as a 'philosopher' in the modern Western sense. Ananda Coomaraswamy has rightly insisted that, The Vedanta is not a philosophy in the current sense of the word, but only as it is used in the phrase Philosophia Perennis... Modern philosophies are closed systems, employing the method of dialectics, and taking for granted that opposites are mutually exclusive.