Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Hotels (WEST)

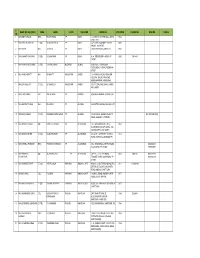

ASIAN HOTELS (WEST)LIMITED Dividend UNPAID REGISTER FOR THE YEAR FINAL DIVIDEND 2012‐2013 Sno Folio/Dpid‐Clid Name Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Pincode Net Amount 1 AHW0300842 VIJAYA KUMAR D‐33, C/O R S CHOPRA, PANCHSHEEL ENCLAVE, NEW DELHI 110017 1960.00 2 AHW0300089 ANATH BANDHU KAPILA KING SAUD UNIVERSITY CELT P O BOX 2456 RIYADH 11451 SAUDI ARABIA 0 2100.00 3 AHW0300218 THOMAS ACQUINAS SEQUEIRA BIN FAHAD TECHNICAL TRADING EST. P.O.BOX 6761, NAJDA STREET ABU DHABI U A E 0 2100.00 4 AHW0300245 DIANA PHILOMENA GLADYS D SOUZA FINANCE DEPARTMENT GOVT. OF ABU DHABI P O BOX 246 ABU DHABI, U.A.E. 0 1904.00 5 AHW0300269 MANIKA DATTA C/O. RANJIT KUMAR DATTA, P.O. BOX ‐ 12068, DUBAI, UAE 0 2800.00 6 AHW0300003 SANJEEV ANAND Y‐10 2ND FLOOR GREEN PARK (MAIN) NEW DELHI 0 70.00 7 AHW0300004 PERGUTTU PRAVEEN CHANDRA PRABHU AIRPORT SERVICES DIRECTORATE P.O.BOX 686 DUBAI UAE 0 350.00 8 AHW0300019 RAMA CHADHA P O BOX 38025‐00623 PARKLANDS POST OFFICE NAIROBI KENYA 0 70.00 9 AHW0300020 GOPAL KRISHNA CHADHA P O BOX 38025‐00623 PARKLANDS POST OFFICE NAIROBI KENYA 0 40.00 10 AHW0300028 SNEHAL HADANI P O BOX 3103 DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 0 50.00 11 AHW0300031 SNEHAL HADANI P O BOX 3103 DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 0 50.00 12 AHW0300322 GANGA DIN NAMDEV SAURABH VIHAR HARI NAGAR JAITPUR NEW DELHI 1100 10.00 13 AHW0300325 MAHATHI M S O‐50, GROUND FLOOR SRINIVAS PURI NEW DELHI 1100 10.00 14 AHW0300328 MOHD ASLAM B/78, PRESIDENT ESTATE SECTION (B) NEW DELHI 1100 20.00 15 AHW0300331 RAJESH RAO FLAT NO 216, F‐2 BLOCK CHARMWOOD VILLAGE S K ROAD FARIDABAD 1210 10.00 16 AHW0300332 DEEPAK BHATIA H NO 1046 SECTOR ‐ 17B IFFCO NAGAR GURGAON 1220 140.00 17 AHW0300336 VINOD CHABRA B I 1407 CHHOWNI MOHALLA LUDHIANA 1410 70.00 18 AHW0300355 HARI OM GAUTAM B‐79, SECTOR ‐14, NOIDA U.P. -

AHE Unpaid in PDF 2014

ASIAN HOTELS EAST LIMITED - UNPAID DIVIDEND DATA FOR THE FY 2011-12 Proposed Date Father/Husb Father/Husb of transfer to and and Middle Father/Husband Pincod Folio No of Amount Due IEPF (DD-MON- SLNO First Name Middle Name Last Name FirstName Name Last Name Address Country State District e Securities Investment Type in Rs. YYYY) P O BOX 23861 SAFAT 13099 Amount for unclaimed 1 THEEYATTU PARAMPIL KURIAN VARKEY T P J KURIAN TECHNICIAN KUWAIT NA NA AHE0300104 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 SAFAT KUWAIT and unpaid dividend C/O. RANJIT KUMAR DATTA, P.O. UNITED ARAB Amount for unclaimed 2 MANIKA DATTA RANJIT K DATTA NA NA AHE0300269 6,300.00 24-AUG-2019 BOX - 12068, DUBAI, UAE EMIRATES and unpaid dividend ANAGHA,URAKAM THRISSUR Amount for unclaimed 3 M JAYAKUMARAN C N MENON SERVICE INDIA KERALA TRICHUR 680562 AHE0305174 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 DISTT. KERALA and unpaid dividend 25 HEERABAGH FLAT G-1 UTTAR Amount for unclaimed 4 ARATI PRAKASH SH ANAND PRAKASH INDIA AGRA 282005 AHE0302350 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 DAYALBAGH, AGRA PRADESH and unpaid dividend 25 HEERABAGH FALT G-1 UTTAR Amount for unclaimed 5 SHIROMAN PRAKASH SH ANAND PRAKASH INDIA AGRA 282005 AHE0302351 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 DAYALBAGH AGRA PRADESH and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed 6 MANJIT SINGH SOHAL V S SOHAL SERVICE COL Q HQ 12 CORPS C/O 56 APO INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI AHE0300002 225.00 24-AUG-2019 and unpaid dividend AIRPORT SERVICES DIRECTORATE UNITED ARAB Amount for unclaimed 7 PERGUTTU PRAVEEN CHANDRA PRABHUP G PRABHU SERVICE NA NA AHE0300004 788.00 24-AUG-2019 P.O.BOX 686 DUBAI UAE EMIRATES -

78Th ALL INDIA INTER-UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS MEET: 2017-18 ORGANIZING SECRATERY REPORT

78th ALL INDIA INTER-UNIVERSITY ATHLETICS MEET: 2017-18 ACHARYA NAGARJUNA UNIVERSITY 12th to 16th December, 2017 ORGANIZING SECRATERY REPORT Organising University : ACHARYA NAGARJUNA UNIVERSITY Tournament : ATHLETICS MEET Section : MEN & WOMEN Zone : ALL INDIA 1. Date of th a) Commencement of the Tournament : 12 December 2017 th b) Completion of the Tournament : 16 December 2017 2. Competition Schedule: DAY – I (12 -12 - 2017 ): MORNING SESSION Event No. Time Event Category Round 101 06.30 AM 5000 M MEN ROUND 1 102 07.30 AM 5000 M WOMEN ROUND 1 103 08.30 AM 800 M MEN ROUND 1 104 09.30 AM 800 M WOMEN ROUND I 105 10.30 AM 100 M WOMEN ROUND 1 106 11.30 AM 100 M MEN ROUND 1 DAY-I (12 -12 - 2017): AFTERNOON SESSION 107 01.30 PM 100 M WOMEN SEMI FINAL 108 01.30 PM HIGH JUMP MEN QUALIFYING 109 01.30 PM DISCUS THROW MEN QUALIFYING 110 01.45 PM TRIPLE JUMP WOMEN QUALIFYING 111 01.45 PM 100 M MEN SEMI FINAL 112 02.15 PM SHOT PUT WOMEN QUALIFYING 113 02.15 PM 400 M WOMEN ROUND 1 114 03.15 PM 400 M MEN ROUND 1 DAY- II (13 -12 - 2017): MORNING SESSION Event No. Time Event Category Round 201 06.30 AM 5000 M MEN FINAL 202 07.10 AM 5000 M WOMEN FINAL 203 08.00 AM JAVELIN THROW MEN QUALIFYING 204 08.00 AM LONG JUMP MEN QUALIFYING 205 08.00 AM 100 M MEN DECATHLON-1 206 08.30 AM 400M MEN SEMIFINAL 207 09.15 AM 400M WOMEN SEMIFINAL 208 09.15 AM POLEVAULT MEN QUALIFYING 209 10.00AM 100 HURDLES WOMEN ROUND I 210 10.00 AM LONG JUMP MEN DECATHLON -2 211 10.00 AM JAVELIN THROW WOMEN QUALIFYING 1 | P a g e 212 10.45 AM 110 HURDLES MEN ROUND 1 213 11.00 AM SHOT -

PDF: 300 Pages, 5.2 MB

The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: The Bay Area Council Economic Institute wishes to thank the sponsors of this report, whose support was critical to its production: The Economic Institute also wishes to acknowledge the valuable project support provided in India by: Global Reach Emerging Ties Between the San Francisco Bay Area and India A Bay Area Council Economic Institute Report by R. Sean Randolph President & CEO Bay Area Council Economic Institute and Niels Erich Global Business/Transportation Consulting November 2009 Bay Area Council Economic Institute 201 California Street, Suite 1450 San Francisco, CA 94111 (415) 981-7117 (415) 981-6408 Fax [email protected] www.bayareaeconomy.org Rangoli Designs Note The geometric drawings used in the pages of this report, as decorations at the beginnings of paragraphs and repeated in side panels, are grayscale examples of rangoli, an Indian folk art. Traditional rangoli designs are often created on the ground in front of the entrances to homes, using finely ground powders in vivid colors. This ancient art form is believed to have originated from the Indian state of Maharashtra, and it is known by different names, such as kolam or aripana, in other states. Rangoli de- signs are considered to be symbols of good luck and welcome, and are created, usually by women, for special occasions such as festivals (espe- cially Diwali), marriages, and birth ceremonies. Cover Note The cover photo collage depicts the view through a “doorway” defined by the section of a carved doorframe from a Hindu temple that appears on the left. -

0X0a I Don't Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN

0x0a I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt FROHMANN I Don’t Know Gregor Weichbrodt 0x0a Contents I Don’t Know .................................................................4 About This Book .......................................................353 Imprint ........................................................................354 I Don’t Know I’m not well-versed in Literature. Sensibility – what is that? What in God’s name is An Afterword? I haven’t the faintest idea. And concerning Book design, I am fully ignorant. What is ‘A Slipcase’ supposed to mean again, and what the heck is Boriswood? The Canons of page construction – I don’t know what that is. I haven’t got a clue. How am I supposed to make sense of Traditional Chinese bookbinding, and what the hell is an Initial? Containers are a mystery to me. And what about A Post box, and what on earth is The Hollow Nickel Case? An Ammunition box – dunno. Couldn’t tell you. I’m not well-versed in Postal systems. And I don’t know what Bulk mail is or what is supposed to be special about A Catcher pouch. I don’t know what people mean by ‘Bags’. What’s the deal with The Arhuaca mochila, and what is the mystery about A Bin bag? Am I supposed to be familiar with A Carpet bag? How should I know? Cradleboard? Come again? Never heard of it. I have no idea. A Changing bag – never heard of it. I’ve never heard of Carriages. A Dogcart – what does that mean? A Ralli car? Doesn’t ring a bell. I have absolutely no idea. And what the hell is Tandem, and what is the deal with the Mail coach? 4 I don’t know the first thing about Postal system of the United Kingdom. -

AHW Unpaid 31.03.2015 Revised Dated 15.02

ASIAN HOTELS (WEST)LIMITED Dividend UNPAID REGISTER FOR THE YEAR FINAL 2011‐2012 Sno Folio/DPID/CLID Name Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Pincode Net Amount 1 AHW0300464 P C GULATI M/S MITSUBISHI CORPORATION VIJAYA 17 BARAKHAMBA ROAD NEW DELHI 110001 2240.00 2 AHW0300585 ABDUL MAJID 1557 RODGRAN FARASH KHANA DELHI 110006 2940.00 3 AHW0300952 AMISHA ANEJA H NO 45, MANDAKINI ENCLAVE SFS ALAKNANDA GREATER KAILASH ‐ II NEW DELHI 110019 2060.00 4 AHW0301052 TARLOCHAN SINGH 23/41 PUNJABI BAGH NEW DELHI 110026 2660.00 5 AHW0301101 KAILASH RANI Y 12/1 LOHA MANDI NARANIA NEW DELHI 110028 2660.00 6 AHW0301102 RAJENDER DANG Y‐12/1 LOHA MANDI NARAINA N DELHI 110028 2660.00 7 AHW0301336 JAI MANGHARAM MUKHI A 27 NEETI BAGH N DELHI 110049 1736.00 8 AHW0301816 SNEHLATA SRIVASTAVA C/O ANUPAM SRIVASTAVA A‐1, CITY APARTMENT VASUNDHARA ENCLAVE DELHI 110096 3500.00 9 AHW0301870 K GOVINDARAJAN A‐302 SHIVALYA GROUP HOUSING SOCIETY SECTOR 56 GURGAON (HARYANA) 122003 1680.00 10 AHW0302164 MASTERVIDIT NAGORY U/G/O ALOK NA7/197, 'MOTI SADAN' SWARUP NAGAR KANPUR U.P 208002 2000.00 11 AHW0302244 ANANT RAM AWASTHI M M S‐2/73, SECTOR ‐ C SITAPUR ROAD SCHEME JANKEE PURAM LUCKNOW, (UP) 226021 1960.00 12 AHW0302529 K S PRADYUMANSINHJI GOVT BUNGLOW NO 32 OPP POLICE STADIUM SHAHIBAG AHMEDABAD 380004 2220.00 13 AHW0302971 JAMSHED BURJOR DALAL 128 WODEHOUSE ROAD COLABA BOMBAY 400005 1960.00 14 AHW0302973 HOMAI BURJOR DALAL MODERN FLATS NO 17‐18 4TH FLOOR 128 WODEHOUSE ROAD COLABA BOMBAY 400005 1736.00 15 AHW0303140 CITI BANK N.A. -

Torch Bearer (Widows)

S NAME OF NOK (WIFE) RANK NAME STATE LOCATION ADDRESS STD CODE PHONE NO MOB NO E-MAIL NO 1 MRS BD KHURANA BRIG BD KHURANA UP AGRA 13, AGRA CLUB, THE MALL, AGRA 0562 CANTT(UP) 2 MRS BK CHATURVEDI LT COL BK CHATURVEDI UP AGRA 34A, AJANTA COLONY, VIBHAV 0562 NAGAR, AGRA (UP) 3 MRS BAHIA MAJ JS BAHIA UP AGRA 10 ASHOK NAGAR, AGRA(UP) 0562 4 MRS SHANTI CHAUHAN LT COL RS CHAUHAN UP AGRA A-34, DEF COLONY, AGRA, UP- 0562 2181469 282001 5 MRS PARI KHAWLHRING LT COL V KHAWLHRING MIZORAM AIZWAL H.NO- M-61, BUNGKAWN TLENGVENG, AIZWAL, MIZORAM- 976001 6 MRS KAMLA BHATT MAJ NR BHATT RAJASTHAN AJMER 1-31 KHANIJ NAGAR, NEAR IBM COLONY , BALALPUR ROAD, ADARSHNAGAR, AJMER(RAJ) 7 MRS SP GANGULY LT COL SP GANGULY RAJASTHAN AJMER 392/4,305001 TODAL MAL MARG, AJMER, RAJ-305001 8 MRS JYOTI SINGH MAJ AMIT KUMAR UP ALIGARH 8/60 MITRA NAGAR, ALIGARH(UP) 9 MRS RAJWATI SINGH MAJ DV SINGH UP ALIGARH 8/59A MITRA NAGAR, ALIGARH (UP) 10 MRS ALKA SINGH LT COL KRISHNA KUMAR SINGH UP ALIGARH 5/266, RISHAL SINGH NAGAR, ITI 9811022780 (SON) ROAD, ALIGARH, UP-202001 11 MRS CHARU KUMAR COL KAMLESH KUMAR UP ALLAHABAD 19 ELGIN ROAD, CIVIL LINES , 0532 ALLAHABAD (C/O CP GOYAL, 102, GOVIND APTS, 249, SAKET, 12 MRS M MUKHARJEE LT COL ML MUKHARJEE UP ALLAHABAD 60,INDORE-452001 GOVT CARPENTRY (MP) SCHOOL 0532 ROAD, KATRA, ALLAHABAD(UP) 13 MRS SHEELA PRAKASH BRIG PRAKASH CHANDRA UP ALLAHABAD 22C, JAWAHARLAL NEHRU ROAD, 9923040311 ALLAHABAD, UP-211002 7769930851 14 MRS PRAKRITI COL SC SRIVASTAVA UP ALLAHABAD 38/22 B, J . -

Peshi Register

PESHI REGISTER Peshi Register From 01-06-2006 To 30-06-2006 Book No. 1 Stamp No. S.No. Reg.No. IstParty IIndParty Type of Deed Address Value Book No. Paid Pandav Nagar 1-- 8136 Swapan Roy , Prabir roy , b-36 RELINQUISHMENT DEED Pandav Nagar , House No. 0.00 100.00 1 b-36, pandav pandav nagar delhi , RELINQUISHMENT ,Road No. 2, Mustail No. , Khasra , nagar delhi DEED Area1 0, Area2 0, Area3 0 Pandav Nagar Pandav Nagar 2-- 7910 Meena kumari , Santosh , 19, patpar SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Pandav Nagar , House No. 100,000.00 6,000.00 1 D-60/A pandav gand delhi AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , nagar delhi Area1 0, Area2 0, Area3 0 Pandav Nagar Pandav Nagar 3-- 8116 Asha Singh , Rajesh singh , c-216 SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Pandav Nagar , House No. 125,000.00 10,000.00 1 c-216, pandav pandav nagar delh i AREA ,Road No. c-216, Mustail No. , Khasra nagar delhi , Area1 0, Area2 0, Area3 0 Pandav Nagar Pandav Nagar 4-- 8071 Shailendra Kumar Amrit goel , 126-b SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Pandav Nagar , House No. 250,000.00 20,000.00 1 Rohatgi , l-4 akash shipra sun city AREA ,Road No. , Mustail No. , Khasra , bharti apartment indrapuram ghaziabad Area1 0, Area2 0, Area3 plot no-24 up 0 Pandav Nagar i.p.extn.delhi Laxmi Nagar 5-- 7216 Peter Gomes , Sylventor gomes , PARTITION , PARTITION Laxmi Nagar , House No. ,Road No. 300,000.00 6,000.00 1 23&23 vijay block 22&23 vijay block 2223, Mustail No. -

WRAP THESIS Tuke 2011.Pdf

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/49539 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Japan’s Foreign Policy towards India: a Neoclassical Realist Analysis of the Policymaking Process Victoria Tuke History BA Hons (Warwick) International Relations MA (Warwick) September 2011 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Politics and International Studies at the University of Warwick. i Victoria Tuke Candidate No: 0415703 Contents List of Tables and Figures ix Abbreviations x Acknowledgements xii Declaration xiii Abstract xiv 1 Introduction 1 I. Research Objective 3 II. Why does this research problem matter? 6 III. Literature Review 7 IV. Contributions of the study 11 V. Argument 12 VI. Research Method 13 i. Primary data 14 ii. Secondary data 18 VII. Organisation of the thesis 19 VIII. Selection of case studies 20 2 Key Debates on Japanese Foreign Policy; Realism, Liberalism, Constructivism and Neoclassical Realism 22 I. Theories of Japanese foreign policy 22 i. Japan as a ‘realist-military’ state 24 ii. The role of ‘gaiatsu’ 26 iii. Japan’s ‘liberal’ economic policy 29 iv. The ‘constructivist turn’ 30 v. An alternative paradigm 33 II. Neoclassical Realism (NCR) – a viable middle approach 34 i. -

640 Words Essay on Swami Vivekanand: a Model of Inspiration for the Young 640 Words Essay on Swami Vivekanand: a Model of Inspiration for the Young

It’s a phenomenal concept to share your original essays… • Home • About Site • Share Your Essay • Contact Us • Subscribe to RSS You are here: Home » 640 Words Essay on Swami Vivekanand: A Model of Inspiration for the Young 640 Words Essay on Swami Vivekanand: A Model of Inspiration for the Young BY DIPTI ON AUGUST 13, 2011 IN ENGLISH ESSAYS “Lives of great men all-remind us, we can make our lives sublime, and departing leave behind us, Footprints on the sands of time.” Swami Vivekananda represents the eternal youth of India. India though possessing a hoary and ancient civilisation is not old and effete, as her detractors would hold but Swami Vivekananda believed that she was young, ripe with potentiality and strong at the beginning of the twentieth century. Swami Vivekananda belonged to the 19th century, yet his message and his life are more relevant today than in the past and perhaps, will be more relevant in future because persons like Swami Vivekananda do not cease to exist with their physical death. Their influence and their thought, the work which they initiate, go on gaining momentum as years pass by, and ultimately, reach a fulfillment which these persons envisaged. Swami Vivekanand himself had said “it may be that I shall find it good to get outside my body to cast it off like a worn out garment but I shall not cease to work! I shall inspire men everywhere, until the world shall know that it is one with god.” The process of this inspiration is spreading all over the world. -

Unity, Democracy, and the All India Phenomenon, 1940-1956 A

Unity, Democracy, and the All India Phenomenon, 1940-1956 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Emily Esther Rook-Koepsel IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ajay Skaria August 2010 © Emily Rook-Koepsel 2010 Acknowledgements We are in the habit of thinking of a dissertation as something done in isolation, each idea and phrase being the author’s alone. Yet, the impressive list of people and organizations who have supported my education, research, and writing is so long as to finally disrupt this farcical image. Without the guidance and patience of my advisor, Ajay Skaria, I would certainly never have made it to this day. He has never failed to respectfully push me to think more seriously and carefully about my ideas. In expecting me to be more and better then I thought I could be, Ajay has made me a better and more thoughtful scholar. Although not officially my advisor, Simona Sawhney has nevertheless been an unfailing source of support, critique, and care. From my first days at the university until now, she has asked me to, ‘say more,’ and with such interest that I have been motivated to try to do just that. At least as importantly, Simona has always demanded not only academic rigor, but a reason for doing the work. That I am as motivated by project as I am can be attributed in large measure to her asking me to defend my project’s purpose. I would also like to thank the remaining members of my committee, Thomas Wolfe, who encouraged me to think about intellectual history, media, and the nation, Cathy Asher, for being a fervent supporter of South Asia scholarship at the University, and Helena Pohlandt-McCormick, who agreed, despite being very busy, to think about my project with me. -

Prospects for E-Advocacy in the Global South

Prospects for e-Advocacy in the Global South A Res Publica Report for the Gates Foundation 1 Project Director Ricken Patel Lead Researcher and Writer Mary Joyce Expert Advisors Katrin Verclas Alan Rosenblatt, Ph.D. Case Study Writers Rishi Chawla, LLB Atieno Ndomo Priscila Néri Gbenga Sesan Idris F Sulaiman, Ph.D. Reviewers Bev Clark, Kubatana.net Rob Faris, OpenNet Initiative Stephanie Hankey, Tactical Technology Collective Janet Haven, Open Society Institute Helen King, Shuttleworth Foundation Paul Maassen, Hivos Sascha Meinrath, IndyMedia Russell Southwood, Balancing Act Africa Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 2.5 License Version 1.0 - January, 2007 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary . 4 Outline of Key Concepts . 6 Introduction . 9 Methodology . 11 I) e-Advocacy in the Global South . 12 Access . 12 Getting Online . 13 The Politics of Access . 14 Censoring ICT . 15 The Digital Divide in Context . 16 The Cellular Savior . 18 Implementation . 22 A Conceptual Framework for e-Advocacy . 22 Data Integration: Collecting Information and Making it Work . 24 Info-Hub: An Online Brochure. 25 CRM: A Dynamic Hub and Spokes . 26 Network-Centric Activism: A Communication Spider Web . 28 Technology Culture. 30 Political Culture . 31 Innovation . 32 Expanding Access: No Technology Succeeds in Isolation . 32 Hybridization: Making Old Technologies New . 33 Peer-to-Peer Mobile Networks . 34 Leapfrogging Borders: Thinking Outside the Geographic Box . 34 II) Funding the Future of Social Change . 36 Values for Funding e-Advocacy in the Global South . 36 Recommendations . 36 Access: End-User Solutions and Policy Change . 38 Implementation: Building e-Advocacy Capacity . 44 Innovation: Shaping the Future . 48 III) Back Matter .