Unity, Democracy, and the All India Phenomenon, 1940-1956 A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prizes 78Th Session

Prizes 78th Session Professor Vijay Kumar Thakur Memorial Prize Dev Kumar Jhanjh, AM-26406 JNU, Delhi Title of Paper: Akṣaśālika, Akṣaśālin and Suvarṇakāra as the Engravers of Copper Plate Charters of Odisha (c.7th-11th Centuries CE) [email protected] Professor J.S. Grewal Prize Damut Skhem Umdor, AM-27567 Nehu, Shillong Title of Paper: Technological Progress in the Pre-Colonial Khasi Society [email protected] Professor Partha Sarathi Gupta Memorial Prize & Professor J.C. Jha Memorial Prize Somdatta Chakraborty, AM-26784 Saltlake City, Kolkata Title of Paper: ‘Striking Work’: Defiance and Resistance by the Land Transport Workers and Water Carriers of Colonial Calcutta and Bengal [email protected] & Isha Dubey, AM-27528 Patna, Bihar, Title of Paper: Navigating the Outsider/Established Divide: Muhajirs in East Pakistan through the Columns of the Daily Pasban [email protected] Professor Sudhir Ranjan Das Memorial Prize Zainab Hussain, AM-27712 AMU, Aligarh Title of Paper: Symbol of Authority: Architectural Study of Minar-i-Jam and Qutb Minar [email protected] Professor Papiya Ghosh Memorial Prize Madhulagna Halder, AM-26735 JNU, New Delhi Title of Paper: Cultures of Violence: Calcutta in the Times of Naxalbari 1970-75 [email protected] Dr Gyaneshwari Devi Memorial Prize R Lakshmi, AM-24106 JNU, New Delhi Title of Paper: Piṭāri Temples and the Legacy of Women in the Early Medieval Period: A Study of the Cōḷa Queen Sembiyan Mādēviyār [email protected] Dr I.G. Khan Memorial Prize Suvobrata Sarkar, AM-21212 Burdwan, West Bengal Title of Paper: Electricity and the Traditional Bengali Society: Colonial Calcutta’s Encounter(s) with a Modern Technology [email protected] Dr Nasreen Ahmad Memorial Prize Lekshmi Chandran C P, AM-27640 JNU, New Delhi Title of Paper: The Matrilineal Households within the Brahmanical Social Order in Pre-Colonial Kerala: a Study of Maṇipravāḷaṃ Literary Sources from c.13th to 15th Centuries [email protected] Professor B.B. -

Ultranationalism: a Proposal for a Quiet Withdrawal

I developed an early suspicion of any form of nationalism courtesy of a geography teacher and an imaginary cricket game. As the only student of Chinese origin in a high school in Bangalore, I was asked by my teacher in a benign voice who I would support if India and China played a match. Aside from the ridiculousness of the question 01/05 (China does not even play cricket), the dubious intent behind it was rather clear, even to a teenager. Still, I dutifully replied, “Sir, I will support India,” for which I received a gratified smile and a pat on the head. I was offended less by the crude attempt by someone in power to force a kid to prove his patriotism, than by the outright silliness of the game. If all it took to Lawrence Liang establish the euphoric security of nationalism was that simple answer, I figured there must be something drastically wrong with the question. I Ultranationalism: was left, however, with an uneasy feeling (one that has persisted through the years), not A Proposal for a because I had given a false answer but because I had been forced to answer a false question. The Quiet answer made pragmatic sense in a schoolboy way (you don’t want to piss off someone who is going to be marking your papers), and I hadn’t Withdrawal read King Lear yet to know that the only appropriate response to the question should have been silence. If Cordelia refuses to participate in Lear’s competition of affective intimacy, it is not just the truth, but also the distasteful aesthetics of her sister’s excessive declarations of love, that motivates her withdrawal into silence. -

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-Site

University Faculty Details Page on DU Web-site Title Dr. First Name Santosh Last Name Rai Photograph Kumar Designation Associate Professor Department History Address (Campus) Department of History, Social Science Building University of Delhi, Delhi-110007 (India) (Residence) 29-31,Probyn Road, University Flats,Delhi-110007 Phone No (Campus) 27666659 (Residence)optional Mobile 9818502847 Fax Email [email protected],[email protected] Web-Page http://www.du.ac.in/du/uploads/Faculty%20Profil es/2016/History/Nov2016_history_Santosh.pdf Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D. University of Delhi 2011 M.Phil. University of Delhi 1999 I Division MA in History Kirorimal College, DU 1996 I Division, II Position in University BA Hons.History Kirorimal College, DU 1994 I Division NET (UGC) UGC 1997 National Eligibility Test in History Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role Department of History, Associate Professor Since 28-01-2014 Teaching and Research University of Delhi S.G.T.B. Khalsa College, Associate/Assistant Feb. 2003 to Teaching and Research University of Delhi Professor Jan.2014 Department of History, Research Associate 07-08-1997 to Research and Teaching University of Delhi 06-08-2002 Research Interests / Specialization Specialization relates to the Modern Indian History. Research interests include Social History of Colonial Uttar Pradesh.; Artisanal practices and Caste, Child Labour, Identity formation and Popular Culture. Teaching Experience ( Subjects/Courses Taught) a. M.Phil. Classes: i.M.Phil. (Course 2): Reading Primary Sources, 2014,2017-18. ii.M.Phil. (Course 3): Problems in the Historical Study of Society and Culture, 2017,2018. b. Post Graduate Teaching: 4 Years i.M.A. -

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Updated October 17, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44094 Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. -

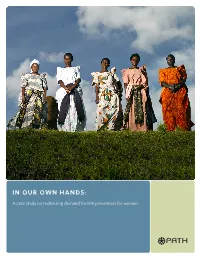

A Case Study on Mobilizing Demand for HIV Prevention for Women PATH Is an International Nonprofit Organization That Transforms Global Health Through Innovation

IN OUR OWN HANDS: A case study on mobilizing demand for HIV prevention for women PATH is an international nonprofit organization that transforms global health through innovation. We take an entrepreneurial approach to developing and delivering high-impact, low-cost solutions, from lifesaving vaccines, drugs, diagnostics, and devices to collaborative programs with communities. Through our work in more than 70 countries, PATH and our partners empower people to achieve their full potential. For more information, please visit www.path.org. 455 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Suite 1000 Washington, DC 20001 [email protected] www.path.org Copyright © 2013, Program for Appropriate Technology in Health (PATH). All rights reserved. Cover photo: Frank Herholdt/Microbicides Development Programme IN OUR OWN HANDS: A case study on mobilizing demand for HIV prevention for women By Anna Forbes, Samukeliso Dube, Megan Gottemoeller, Pauline Irungu, Bindiya Patel, Ananthy Thambinayagam, Rebekah Webb, and Katie West Slevin The authors would like to thank the staff of the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College for their invaluable assistance. As the oldest US collection of women’s history manuscripts and archives, the Collection now houses the Global Campaign for Microbicides (GCM) files. The authors would also like to acknowledge all the funders whose support made GCM’s work possible. Most of all, we would like to thank the thousands of women and men who endorsed, supported, and partnered with GCM in doing this work and who are carrying it forward in other ways -

The Fatal Flame

pT Lit 003 Rakhshanda Jalil’s translation of Gulzar’s short story Dhuaan wins the inaugural Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-English translation The fatal flame alpix 0761 Dr Rakhshanda Jalil Publisher : Hachette UK BA Eng Hons 1984 MH MA Eng 1986 LSR Writer Late last week, it was announced that Delhi-based writer, critic and literary historian Rakhshanda Jalil would be awarded the inaugural Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-english translation, instituted in the memory of Urdu poet and scholar Ali Jawad Zaidi by his family, on the occasion of his birth centenary. A recipient of the Padma Shri, the Ghalib Award and the Mir Anis award, Zaidi had to his name several books of ghazals and nazms, scholarly works on Urdu literature, including The History Of Urdu Literature, and was working on a book called Urdu Mein Ramkatha when he died in 2004. Considering that much of Zaidi’s work “served as a bridge between languages and cultures”, his family felt the best way to honour his literary legacy would be to focus on translations. Since the prize was to be given to a short story in translation in the first year, submissions of an unpublished translation of a published Urdu story were sought. While Jalil won the prize, the joint runners-up were Fatima Rizvi, who teaches literature at the University of Lucknow, and Pakistani social scientist and critic Raza Naeem. The judges, authors Tabish Khair and Musharraf Ali Farooqi, chose to award Jalil for her “careful, and even” translation of a story by Gulzar, Dhuaan (Smoke), “which talks about the violence and tragic absurdity of religious prejudice”. -

Asian Hotels (WEST)

ASIAN HOTELS (WEST)LIMITED Dividend UNPAID REGISTER FOR THE YEAR FINAL DIVIDEND 2012‐2013 Sno Folio/Dpid‐Clid Name Address1 Address2 Address3 Address4 Pincode Net Amount 1 AHW0300842 VIJAYA KUMAR D‐33, C/O R S CHOPRA, PANCHSHEEL ENCLAVE, NEW DELHI 110017 1960.00 2 AHW0300089 ANATH BANDHU KAPILA KING SAUD UNIVERSITY CELT P O BOX 2456 RIYADH 11451 SAUDI ARABIA 0 2100.00 3 AHW0300218 THOMAS ACQUINAS SEQUEIRA BIN FAHAD TECHNICAL TRADING EST. P.O.BOX 6761, NAJDA STREET ABU DHABI U A E 0 2100.00 4 AHW0300245 DIANA PHILOMENA GLADYS D SOUZA FINANCE DEPARTMENT GOVT. OF ABU DHABI P O BOX 246 ABU DHABI, U.A.E. 0 1904.00 5 AHW0300269 MANIKA DATTA C/O. RANJIT KUMAR DATTA, P.O. BOX ‐ 12068, DUBAI, UAE 0 2800.00 6 AHW0300003 SANJEEV ANAND Y‐10 2ND FLOOR GREEN PARK (MAIN) NEW DELHI 0 70.00 7 AHW0300004 PERGUTTU PRAVEEN CHANDRA PRABHU AIRPORT SERVICES DIRECTORATE P.O.BOX 686 DUBAI UAE 0 350.00 8 AHW0300019 RAMA CHADHA P O BOX 38025‐00623 PARKLANDS POST OFFICE NAIROBI KENYA 0 70.00 9 AHW0300020 GOPAL KRISHNA CHADHA P O BOX 38025‐00623 PARKLANDS POST OFFICE NAIROBI KENYA 0 40.00 10 AHW0300028 SNEHAL HADANI P O BOX 3103 DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 0 50.00 11 AHW0300031 SNEHAL HADANI P O BOX 3103 DUBAI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 0 50.00 12 AHW0300322 GANGA DIN NAMDEV SAURABH VIHAR HARI NAGAR JAITPUR NEW DELHI 1100 10.00 13 AHW0300325 MAHATHI M S O‐50, GROUND FLOOR SRINIVAS PURI NEW DELHI 1100 10.00 14 AHW0300328 MOHD ASLAM B/78, PRESIDENT ESTATE SECTION (B) NEW DELHI 1100 20.00 15 AHW0300331 RAJESH RAO FLAT NO 216, F‐2 BLOCK CHARMWOOD VILLAGE S K ROAD FARIDABAD 1210 10.00 16 AHW0300332 DEEPAK BHATIA H NO 1046 SECTOR ‐ 17B IFFCO NAGAR GURGAON 1220 140.00 17 AHW0300336 VINOD CHABRA B I 1407 CHHOWNI MOHALLA LUDHIANA 1410 70.00 18 AHW0300355 HARI OM GAUTAM B‐79, SECTOR ‐14, NOIDA U.P. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

AHE Unpaid in PDF 2014

ASIAN HOTELS EAST LIMITED - UNPAID DIVIDEND DATA FOR THE FY 2011-12 Proposed Date Father/Husb Father/Husb of transfer to and and Middle Father/Husband Pincod Folio No of Amount Due IEPF (DD-MON- SLNO First Name Middle Name Last Name FirstName Name Last Name Address Country State District e Securities Investment Type in Rs. YYYY) P O BOX 23861 SAFAT 13099 Amount for unclaimed 1 THEEYATTU PARAMPIL KURIAN VARKEY T P J KURIAN TECHNICIAN KUWAIT NA NA AHE0300104 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 SAFAT KUWAIT and unpaid dividend C/O. RANJIT KUMAR DATTA, P.O. UNITED ARAB Amount for unclaimed 2 MANIKA DATTA RANJIT K DATTA NA NA AHE0300269 6,300.00 24-AUG-2019 BOX - 12068, DUBAI, UAE EMIRATES and unpaid dividend ANAGHA,URAKAM THRISSUR Amount for unclaimed 3 M JAYAKUMARAN C N MENON SERVICE INDIA KERALA TRICHUR 680562 AHE0305174 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 DISTT. KERALA and unpaid dividend 25 HEERABAGH FLAT G-1 UTTAR Amount for unclaimed 4 ARATI PRAKASH SH ANAND PRAKASH INDIA AGRA 282005 AHE0302350 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 DAYALBAGH, AGRA PRADESH and unpaid dividend 25 HEERABAGH FALT G-1 UTTAR Amount for unclaimed 5 SHIROMAN PRAKASH SH ANAND PRAKASH INDIA AGRA 282005 AHE0302351 3,150.00 24-AUG-2019 DAYALBAGH AGRA PRADESH and unpaid dividend Amount for unclaimed 6 MANJIT SINGH SOHAL V S SOHAL SERVICE COL Q HQ 12 CORPS C/O 56 APO INDIA DELHI NEW DELHI AHE0300002 225.00 24-AUG-2019 and unpaid dividend AIRPORT SERVICES DIRECTORATE UNITED ARAB Amount for unclaimed 7 PERGUTTU PRAVEEN CHANDRA PRABHUP G PRABHU SERVICE NA NA AHE0300004 788.00 24-AUG-2019 P.O.BOX 686 DUBAI UAE EMIRATES -

Reconsidering Solidarity with Leela Gandhi and Judith Butler

Europe’s Crisis: Reconsidering Solidarity with Leela Gandhi and Judith Butler Giovanna Covi for William V. Spanos, who has shown the way The idea called Europe is important. It deserves loving and nourishing care to grow well and to return its promise. It is a visionary idea shared by winners and losers of World War II, by survivors of the Nazi-Fascist regimes and the Shoah, by large and small countries. It is still little more than just an idea: so far, it has only yielded the suspension of inner wars among the states that became members of the European Union. It is only a germ. Yet, its achievement is outstanding: in the face of the incessant proliferation of wars around the globe, it has secured lasting peace to an increasing number of nations since the 1950s. The idea called Europe is also vague. It has pursued its aim of ending the frequent and bloody wars between neighbours mainly through economic ties, as the Treaty of Maastricht’s failure to promote shared policies underscores. For over half a century, its common policies have been manifestly insufficient and inadequate. It is indeed still only a germ. And its limitations are tremendous: in the face of the rising threats to its own idea of peaceful cohabitation, of the internal rise of violent and hateful forces of sovereignty, of policies of domination, discrimination and exclusion, it is incapable of keeping Europe’s own promise. Such limitations are tangible in the debate about Grexit and the decision regarding Brexit, as well as in the political turn towards totalitarianisms in multiple states. -

Swan IEPF Shares for 2009-2010

Swan Energy Limited List of Share Holder - 2009-2010 SHARES FIRST SECOND THIRD FIRST HOLDER SECOND HOLDER THIRD HOLDER FOLIO NUMBER TRANSFERRED HOLDER HOLDER HOLDER ADDRESS NAME NAME NAME TO IEPF PAN PAN PAN BALOOBHAI MRS PRATIBHA 16 MARIPOSA PLACE, OLD BRIDGE, N J 029341 100 GORDHANBHAI PATEL BALOOBHAI 08857,USA - HEMENDRA MRS SUDHA 002228 300 ISHWARLAL DALAL HEMENDRA DALAL HARIPURA HATH FALIA SURAT -0 MRS SAVITABEN CHHABILPRASAD CHHABILPRASAD G NO 14/364 3RD FLOOR N R G COLONY 002242 100 RATILAL UPADHYAYA UPADHYAYA MOHONETHANE -0 MOHSHINBHAI MRS SAGARABAI 003134 200 HAJDARBHAI MOHSHINBHAI BHAGATAL ROAD SURAT -0 26 DHARENDRA SOCIETY 3RD FLOOR S V BAHADURSINH MRS MAYA ROAD OPP TELEPHONE EXCHANGE MALAD 004018 600 MOHANSINH JADEJA BAHADURSINH JADEJA (WEST)MUMBAI -0 C/O SHANTILAL NANCHAND SHAH BUNGALOW NO 11 ARUDHATI PARK CHANDRIKABEN MR SHANTILAL BHAIRAVNATH ROAD 004130 100 SHANTILAL SHAH NANCHAND SHAH MANINAGARAHMEDABA -0 SAHARKAR NAGAR NO-2 SHARDA VASANT GHANSHYAM MRS MANIBAI APARTMENT FLAT NO-2 88-1-5 PARVATIPUNE - 005037 200 UPADHYAYA VITHALDAS THAKER 0 MR GIRISH KUMAR C/O GORDHANLAL OJHA PUNJAB NATIONAL 005209 100 DURGA DEVI OJHA OJHA BANK UDAIPUR -0 GUNWANTI 005287 200 MOHANLAL MEHTA MANDVINI POLE DEV SHERI AHMEDABAD -0 SHANTILAL MR SUDHAKAR MULCHANDBHAI RANCHHODLAL 611 DEV SHERI LAKHA PATELS STREET 005290 500 CHOKSI CHOKSI SANKDI SHERI AHMEDABAD -0 TULSIDAS JOITRAM RAIPUR BUNGALANI POLE HOUSE NO 2373 005327 500 PATEL AHMEDABAD -0 KESARISINGH 005343 200 VADILAL ZAVERI ZAVERIWADA ZAVERI POLE AHMEDABAD -0 ASTOD DINESHAH 022034 900 GORWALA -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known.