Architecture in Central India Under the Kacchapaghata Rulers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

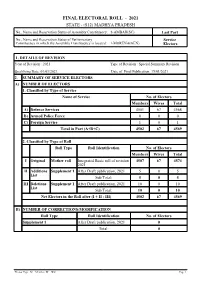

Final Electoral Roll

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL - 2021 STATE - (S12) MADHYA PRADESH No., Name and Reservation Status of Assembly Constituency: 8-AMBAH(SC) Last Part No., Name and Reservation Status of Parliamentary Service Constituency in which the Assembly Constituency is located: 1-MORENA(GEN) Electors 1. DETAILS OF REVISION Year of Revision : 2021 Type of Revision : Special Summary Revision Qualifying Date :01/01/2021 Date of Final Publication: 15/01/2021 2. SUMMARY OF SERVICE ELECTORS A) NUMBER OF ELECTORS 1. Classified by Type of Service Name of Service No. of Electors Members Wives Total A) Defence Services 4501 67 4568 B) Armed Police Force 0 0 0 C) Foreign Service 1 0 1 Total in Part (A+B+C) 4502 67 4569 2. Classified by Type of Roll Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Members Wives Total I Original Mother roll Integrated Basic roll of revision 4507 67 4574 2021 II Additions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 5 0 5 List Sub Total: 5 0 5 III Deletions Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 10 0 10 List Sub Total: 10 0 10 Net Electors in the Roll after (I + II - III) 4502 67 4569 B) NUMBER OF CORRECTIONS/MODIFICATION Roll Type Roll Identification No. of Electors Supplement 1 After Draft publication, 2021 0 Total: 0 Elector Type: M = Member, W = Wife Page 1 Final Electoral Roll, 2021 of Assembly Constituency 8-AMBAH (SC), (S12) MADHYA PRADESH A . Defence Services Sl.No Name of Elector Elector Rank Husband's Address of Record House Address Type Sl.No. Officer/Commanding Officer for despatch of Ballot Paper (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) Assam -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory . -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Jain Philosophy and Practice I 1

PANCHA PARAMESTHI Chapter 01 - Pancha Paramesthi Namo Arihantänam: I bow down to Arihanta, Namo Siddhänam: I bow down to Siddha, Namo Äyariyänam: I bow down to Ächärya, Namo Uvajjhäyänam: I bow down to Upädhyäy, Namo Loe Savva-Sähunam: I bow down to Sädhu and Sädhvi. Eso Pancha Namokkäro: These five fold reverence (bowings downs), Savva-Pävappanäsano: Destroy all the sins, Manglänancha Savvesim: Amongst all that is auspicious, Padhamam Havai Mangalam: This Navakär Mantra is the foremost. The Navakär Mantra is the most important mantra in Jainism and can be recited at any time. While reciting the Navakär Mantra, we bow down to Arihanta (souls who have reached the state of non-attachment towards worldly matters), Siddhas (liberated souls), Ächäryas (heads of Sädhus and Sädhvis), Upädhyäys (those who teach scriptures and Jain principles to the followers), and all (Sädhus and Sädhvis (monks and nuns, who have voluntarily given up social, economical and family relationships). Together, they are called Pancha Paramesthi (The five supreme spiritual people). In this Mantra we worship their virtues rather than worshipping any one particular entity; therefore, the Mantra is not named after Lord Mahävir, Lord Pärshva- Näth or Ädi-Näth, etc. When we recite Navakär Mantra, it also reminds us that, we need to be like them. This mantra is also called Namaskär or Namokär Mantra because in this Mantra we offer Namaskär (bowing down) to these five supreme group beings. Recitation of the Navakär Mantra creates positive vibrations around us, and repels negative ones. The Navakär Mantra contains the foremost message of Jainism. The message is very clear. -

The Birth of Jainism Mahavira the Path-Maker

JAINISM - RESPECT FOR ALL LIFE: By Myrtle Langley For a religion of only 3 million people, almost all of whom live in India, Jainism has wielded an influence out of all proportion to its size and its distribution. This influence has been felt most keenly in the modern world through Mahatma Gandhi. Although not himself a Jain, he grew up among Jains and embraced their most distinctive doctrine; non-violence to living beings (Ahimsa). But the influence of Jainism has also been felt in the Jain contribution to India’s banking and commercial life. As Buddhists are followers of the Buddha (the enlightened one), so Jains are the followers of the Jina (the conqueror), a title applied to Vardhamana, last of the great Jain teachers. It is applied also to those men and women who, having conquered their passions and emotions, have achieved liberation and attained perfection. And so the very name Jainism indicates the predominantly ethical character of this religion. THE BIRTH OF JAINISM The period from the seventh to the fifth centuries BC was a turning point in the intellectual and spiritual development of the whole world: it produced, among others, the early Greek philosophers, the great Hebrew prophets, Confucius in China and Zoroaster in Persia. For north India, the sixth century BC was a time of particular social, political and intellectual ferment. The older and more familiar tribal structure of society was disintegrating. In its place were appearing a few great regional kingdoms and a number of smaller tribal groupings known, as republics. These kept some of the characteristics of tribal structure but had little political power, being dependent on the largest of the kingdoms. -

Notes on Modern Jainism

'J UN11 JUI .UBRARYQr c? IEUNIVER%. fHONVSOV | I ! 1 I i r^ 5, 3 ? \E-UNIVER. <~> **- 1 S 'OUJMVJ'iU ' il g i i i I s fc i<^ vvlOS-ANCELfX^ " - ^ <tx-N__^ # = =3 1( ^ Af-UNIVfl% il I fe ^'^ t $ ^ ^*-~- ^ ^ NOTES ON MODERN JAINISM WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE S'VETA'MBARA, DIGAMBARA AND STHA'NAKAVA'SI SECTS. BY MRS. SINCLAIR STEVENSON, M.A. (T.C.D.) SOMETIME SCHOLAR OF SOMERVILLE COLLEGE, OXFORD. OXFORD S i B. H. BLACKWELL, 50 & 51 BROAD REET LONDON SIMPKIN, MARSHALL & Co, LIMITED SURAT : IRISH MISSION PRESS 1910. Stack Annfv r 333 HVNC LIBELLVM DE TRISTS VITAE SEVERITATE CVM MEAE TVM MARITI MATR! MEMORiAE MONVMENTVM DEDICO QVAE EXEMPLVM LONGE ALIVM SECVTAE NOMEN MATERNVM TAM FELICITER ORNAVERVNT. ** 2029268 PREFACE. THESE notes on Jain ism have been compiled mainly from information supplied to me by Gujarati speaking Jaina, so it has seemed advisable to use the Gujarati forms of their technical terms. It would be impossible to issue this little book without expressing my indebtedness to the Rev. G. P. Taylor, D. D., Principal of the Fleming Stevenson Divinity College, Ahmedabad, who placed all the resources of his valuable library at my disposal, and also to the various Jaina friends who so courteously bore with my interminable questionings. I am specially grateful to a learned Jaina gentleman who read through all the MS. with me, and thereby saved me, I hope, from some of the numerous pitfalls which beset the pathway of anyone who ventures to explore an alien faith. MARGARET STEVENSON. Irish Mission, Rajkot. India. -

Programme Du Voyage

Forts, palais, temples et villages du Malwa Architecture et iconographie hindoues aux confins occidentaux du Madhya Pradesh, Inde Centrale du 28 janvier au 18 février 2022 Votre conférencier Au cœur du Madhya Pradesh, dans un environnement Gérard Rovillé majoritairement rural, subsistent de nombreux Diplômé d'Ethnologie - témoignages de ce que fut l’évolution de l’architecture et Anthropologie et Sciences des de l’iconographie hindoues du Ve au XIIe siècle, lorsque Religions des dynasties, souvent concurrentes, souvent également issues de clans rajpoutes, redonnèrent la prééminence aux divinités vishnouïtes et shivaïtes, ou jaïnes, après des siècles de bouddhisme triomphant. Ce thème sera le fil rouge de ce voyage destiné, de préférence, à des Les points forts voyageurs ayant déjà eu une première approche de l’Inde L’évolution des temples hindous en Inde du et qui s’intéressent au développement de l’architecture et Nord du VIe au XIIe siècle de l’iconographie des temples hindous. Toutefois, Deux journées et demi à Gwalior l’itinéraire se déployant à travers les campagnes La découverte des districts de Nimuch, vallonnées et les grandes vallées (Chambal, Sind) du Mandsaur et Ratlam centre de l’Inde du Nord, le milieu rural indien sera bien Les monastères-fortifiés des gourous- évidemment abordé et des promenades en villages soldats Mattayamura prévues. A l’écart des grands axes touristiques, ce périple Le temple de Jhalrapatan permet de découvrir à la fois les paysages des Monts Le temple excavé et les grottes bouddhiques Vindhya et une suite de monuments considérés de Dharmarajeshwar touristiquement comme ‘secondaires’ mais Dhar, l’ancienne capitale du Malwa archéologiquement aussi importants que les plus célèbres Le site de Sultan Garhi à Delhi car ils permettent d’expliquer toute une évolution artistique Les paysages des Monts Vindhya dans ses diverses variations chronologiques et régionales. -

Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi's in Jainism

International Journal of Applied Research 2016; 2(2): 616-618 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Depiction of Yaksha and Yakshi’s in Jainism IJAR 2016; 2(2): 616-618 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 13-12-2015 Dr. Venkatesha TS Accepted: 15-01-2016 Jainism, one of the oldest living faiths of India, has a hoary antiquity in Karnataka. No doubt, Dr. Venkatesha TS UGC-POST Doctoral Fellow this religion took its birth in North India. However, within a couple of centuries of its birth, Department of Studies and this religionis said to have entered into Karnataka. Jaina tradition ascribes III C.B.C. as the Research in History and date of entry of this religion to south India, and in particular to Karnataka. After this period Archaeology Tumkur Jainism grew from strength to strength and heralded a glorious era, never to be witnessed in University, Tumkur-572103 any part of India, to become a religion next only to Brahmanism in popularity and number. Though Jainism was spread over different parts of south India within the first few centuries of the Christian era, its nucleus as well as the stronghold was southern Karnataka. In fact, it is the general opinion that the history of Jainism in south India is predominantly the history of that religion in Karnataka. Such was the prominence that this religion enjoyed throughout the first millennium A.D. Liberal royal patronage extended by the Kadambas, the Gangas, the Chalukyas of Badami, the Rashtrakutas, the Nolambas, the Kalyana Chalukyas, the Hoysalas, the Vijayanagar rulers and their successors, resulted in the uninterrupted growth of this religion in southern Karnataka. -

The Heart of Jainism

;c\j -co THE RELIGIOUS QUEST OF INDIA EDITED BY J. N. FARQUHAR, MA. LITERARY SECRETARY, NATIONAL COUNCIL OF YOUNG MEN S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATIONS, INDIA AND CEYLON AND H. D. GRISWOLD, MA., PH.D. SECRETARY OF THE COUNCIL OF THE AMERICAN PRESBYTERIAN MISSIONS IN INDIA si 7 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME ALREADY PUBLISHED INDIAN THEISM, FROM By NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., THE VEDIC TO THE D.Litt. Pp.xvi + 292. Price MUHAMMADAN 6s. net. PERIOD. IN PREPARATION THE RELIGIOUS LITERA By J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A. TURE OF INDIA. THE RELIGION OF THE By H. D. GRISWOLD, M.A., RIGVEDA. PH.D. THE VEDANTA By A. G. HOGG, M.A., Chris tian College, Madras. HINDU ETHICS By JOHN MCKENZIE, M.A., Wilson College, Bombay. BUDDHISM By K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. ISLAM IN INDIA By H. A. WALTER, M.A., Literary Secretary, National Council of Y.M.C.A., India and Ceylon. JAN 9 1986 EDITORIAL PREFACE THE writers of this series of volumes on the variant forms of religious life in India are governed in their work by two impelling motives. I. They endeavour to work in the sincere and sympathetic spirit of science. They desire to understand the perplexingly involved developments of thought and life in India and dis passionately to estimate their value. They recognize the futility of any such attempt to understand and evaluate, unless it is grounded in a thorough historical study of the phenomena investigated. In recognizing this fact they do no more than share what is common ground among all modern students of religion of any repute. -

Tirthankaras: “Ford Makers”

Jainism Tirthankaras: “Ford Makers” Tirthankaras: “Ford Makers” Summary: Mahavira was just one of a larger cycle of 24 tirthankaras (Ford-makers), religious pioneers who reveal the truth of Jainism to humanity. Mahavira stands as 24th in the sequence, the final tirthankara of this age. Mahavira is known as a Tirthankara, literally, a “ford-maker,” a spiritual pioneer who is able to ford the river, to cross beyond the perpetual flow of earthly life. Jains do not believe in the concepts of universal creator, or moment of creation. According to the Jain view, time has no beginning and no end; rather, it is a perpetual cycle of ascent and decline, one of six metaphysical principles that Jains believe comprise the universe. Times of descent, such as our own, are so clouded with materialism and ignorance that achieving luminous self-realization is very difficult. In each cycle of time there are 24 tirthankaras who are trail-blazers for the rest of humanity. The tirthankaras, it must be stressed, are souls, the same as all other souls. But in addition to liberating themselves as jinas, the tirthankaras spend their lives as teachers, sharing their knowledge with others. The very first tirthankara was Adinath, also called Rishabha Deva. The 23rd was Parshvanath, who is said to have lived toward the beginning of the first millennium BCE. The 24th and last tirthankara in the current cycle was Mahavira, who lived in the 6th century BCE—about the same time as the Buddha. The tirthankaras are, in one sense, identical, for in the era in which each lived, they taught a truth that is eternal. -

Initial Environmental Examination (Draft)

Initial Environmental Examination (Draft) November 2013 IND: Madhya Pradesh Power Transmission and Distribution System Improvement Project Prepared by the Madhya Pradesh Power Transmission Corporation Ltd. (MP Transco), Madhya Pradesh Madhya Kshetra Vidyut Vitaran Company (DISCOM-C), Madhya Pradesh Poorva Kshetra Vidyut Vitaran Company (DISCOM-E), and Madhya Pradesh Paschim Kshetra Vidyut Vitaran Company (DISCOM-W) for the Asian Development Bank The initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Overview of the Project 4 1.2 The Need for an Initial Environmental Examination 6 1.3 Structure of the Report 6 2.0 POLICY, LEGAL, AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK 8 2.1 ADB Safeguard Policy Statement 2009 8 2.2 Applicable National and State Legislation 8 2.3 National and State Environmental Assessment Requirements 9 2.4 Applicable International Environmental Agreements 12 2.5 Other Applicable Laws and Policies 13 3.0 DESCRIPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT 14 3.1 Physical Resources 14 3.2 Biological Resources 19 3.3 Socioeconomic Profile 22 4.0 POWER TRANSMISSION SYSTEM IMPROVEMENT 25 4.1 Project Description 25 4.2 Analysis of Alternatives 28 4.3 Anticipated Environmental Impacts and Mitigation Measures 30 4.4 Information Disclosure, Consultation, and Participation 39 4.5 Grievance Redress Mechanism 40 4.6 Environmental -

47100-004: Madhya Pradesh Power Transmission and Distribution

Initial Environment Examination Project Number: 47100-004 January 2019 IND: Madhya Pradesh Power Transmission and Distribution System Improvement Project Submitted by Madhya Pradesh Madhya Kshetra Vidyut Vitaran Co. Ltd. (DISCOM-C), Bhopal This initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. This report is an updated version of the IEE report posted in September 2013 available on https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/madhya-pradesh-power-transmission-distribution-system- improvement-project-iee. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION [IEE] REPORT November 2018 Madhya Pradesh Madhya Keshtra Vidyut Vitaran Co. Limited- DISCOM-Central, Nishtha Parisar, Govindpura, Bhopal (MP) Power Transmission and Distribution System Improvement Project under ADB Loan-No -3066 IND Prepared by: Environmental Planning and Coordination Organization [EPCO], Bhopal, Department of Environment, Government of Madhya Pradesh The initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB‟s Board of Directors, Management, or