Ancient Punjab – Volume 8, 2020 37

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MATCH UPDATES and TIME TABLE of Pakistan Super League 2021 S.NO

MATCH UPDATES AND TIME TABLE Of Pakistan Super League 2021 S.NO. Date Time (IST) Match Venue 1. February 20 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Quetta Gladiators Karachi 2. February 21 2:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Multan Sultans Karachi 3. February 21 7:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Multan Sultans Karachi 4. February 22 7:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 5. February 23 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 6 February 24 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Islamabad United Karachi 7. February 26 2:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 8. February 26 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 9. February 27 2:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Multan Sultans Karachi 10. February 27 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi National Stadium, vs Islamabad Karachi United 11. February 28 7:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Lahore Qalandars Karachi 12. March 1 7:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, vs Quetta Karachi Gladiators 13. March 3 2:30 PM Karachi Kings vs National Stadium, Peshawar Zalmi Karachi 14. March 3 7:30 PM Quetta Gladiators National Stadium, vs Multan Sultans Karachi 15. March 4 7:30 PM Lahore Qalandars National Stadium, vs Islamabad Karachi United 16 March 5 7:30 PM Multan Sultans vs National Stadium, Karachi Kings Karachi 17. March 6 2:30 PM Islamabad United National Stadium, v Quetta Karachi Gladiators 18. March 6 7:30 PM Peshawar Zalmi v National Stadium, Lahore Qalandars Karachi 19. -

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Sialkot District Reference Map September, 2014

74°0'0"E G SIALKOT DISTRICT REFBHEIMRBEER NCE MAP SEPTEMBER, 2014 Legend !> GF !> !> Health Facility Education Facility !>G !> ARZO TRUST BHU CHITTI HOSPITAL & SHEIKHAN !> MEDICAL STORE !> Sialkot City !> G Basic Health Unit !> High School !> !> !> G !> MURAD PUR BASHIR A CHAUDHARY AL-SHEIKH HOSPITAL JINNAH MEMORIAL !> MEMORIAL HOSPITAL "' CHRISTIAN HOSPITAL ÷Ó Children Hospital !> Higher Secondary IQBAL !> !> HOSPITAL !>G G DISPENSARY HOSPITAL CHILDREN !> a !> G BHAGWAL DHQ c D AL-KHIDMAT HOSPITAL OA !> SIALKOT R Dispensary AWAN BETHANIA !>CHILDREN !>a T GF !> Primary School GF cca ÷Ó!> !> A WOMEN M!>EDICAaL COMPLEX HOSPITAL HOSPITAL !> ÷Ó JW c ÷Ó !> '" A !B B D AL-SHIFA HOSPITAL !> '" E ÷Ó !> F a !> '" !B R E QURESHI HOScPITAL !> ALI HUSSAIN DHQ O N !> University A C BUKH!>ARI H M D E !>!>!> GENERAL E !> !> A A ZOHRA DISPENSARY AG!>HA ASAR HOSPITAL D R R W A !B GF L AL-KHAIR !> !> HEALTH O O A '" Rural Health Center N MEMORIAL !> HOSPITAL A N " !B R " ú !B a CENTER !> D úK Bridge 0 HOSPITAL HOSPITAL c Z !> 0 ' A S ú ' D F úú 0 AL-KHAIR aA 0 !> !>E R UR ROA 4 cR P D 4 F O W SAID ° GENERAL R E A L- ° GUJORNAT !> AD L !> NDA 2 !> GO 2 A!>!>C IQBAL BEGUM FREE DISPENSARY G '" '" Sub-Health Center 3 HOSPITAL D E !> INDIAN 3 a !> !>!> úú BHU Police Station AAMNA MEDICAL CENTER D MUGHAL HOSPIT!>AL PASRUR RD HAIDER !> !>!> c !> !>E !> !> GONDAL G F Z G !>R E PARK SIALKOT !> AF BHU O N !> AR A C GF W SIDDIQUE D E R A TB UGGOKI BHU OA L d ALI VETERINARY CLINIC D CHARITABLE BHU GF OCCUPIED !X Railway Station LODHREY !> ALI G !> G AWAN Z D MALAGAR -

Sr. No College Name District Gender Division Contact 1 GOVT

Sr. College Name District Gender Division Contact No 1 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572613336 2 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN FATEH JANG, ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572212505 3 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN PINDI GHEB, ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 4 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, JAND ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572621847 5 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN HASSAN ABDAL ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 6 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN HAZRO, ATTOCK ATTOCK Female RAWALPINDI 572312884 7 GOVT. POST GRADUATE COLLEGE ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 579316163 8 Govt. Commerce College, Attock ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 9 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FATEH JANG ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 10 GOVT. INTER COLLEGE OF BOYS, BAHTAR, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 11 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE (BOYS) PINDI GHEB ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572352909 12 Govt. Institute of Commerce, Pindigheb ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572352470 13 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE BOYS, JAND, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572622310 14 GOVT. INTER COLLEGE NARRAH KANJOOR CHHAB ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572624005 15 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE BASAL ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572631414 16 Govt. Institute of Commerce, Jand ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572621186 17 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR BOYS HASSAN ABDAL, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 18 GOVT.SHUJA KHANZADA SHAHEED DEGREE COLLEGE, HAZRO, ATTOCK ATTOCK Male RAWALPINDI 572312612 19 GOVT. COLLEGE FOR WOMEN CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543550957 20 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN , DHADIAL , CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543590066 21 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN MULHAL MUGHLAN, CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543585081 22 GOVT. DEGREE COLLEGE FOR WOMEN BALKASSAR , CHAKWAL CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543569888 23 Govt Degree College for women Ara Basharat tehsil choa Saidan Shah chakwal CHAKWAL Female RAWALPINDI 543579210 24 GOVT. -

PRCS Sitrep No.6, Monsoon Floods 15Th Sep, 14

MONSOON 2014 Info Report - 6: Dated 15-09-14 18-09- HIGHLIGHT Forecast from Pakistan Meteorological Department says “Seasonal low lies over north Baluchistan and adjoining areas. A shallow trough of westerly wave is also prevailing over Kashmir and adjoining areas”. As per the report of NDMA dated 14th September, 2014, Monsoon rains have affected 2,459,704 individuals caused 301 deaths and 507 people got injured in AJK, Punjab and GB. As per UNOCH report of 11th September, the authorities expect an estimated 3 million people to be affected by the floods in the coming days. PRCS is responding in Punjab, AJK, GB and Sindh with an initial plan to assist 13,000 families (91,000 indiv), with provision of food, non food items, emergency shelter and health and care services. In Punjab three PRCS health units have already started working and disaster preparedness stocks are being sent to the affected districts for distribution. So far PRCS Punjab Provincial Branch has distributed 2,350 x food packs to the flood affected families of Jhang, Sialkot, Shikarpur, Chinniot, Gujrat, Hafizabad and Toba Take Singh. In GB 70 x NFIs have been distributed among the flood affected families of Astor District. In AJK 840 families have been assisted with provision of emergency shelter and NFIs in district Bagh, Poonch, Haveli and Muzafarabad. 2 MHUs have also been deployed in District Haveli today. So far, 51 patients were treated in Hallan Shamil of Union Council Kala Mula, District Haveli. than 15,200 flood afected people all over Pakistan with services including food and non food items provision, 1.WEATHER OUTLOOK (as of 15th Sep,2014 at 1045 hrs by pak met) HYDROLOGICAL SITUATION: River Chenab at Punjnad is in High Flood Level. -

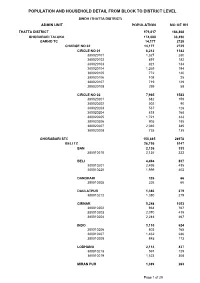

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH THATTA DISTRICT 979,817 184,868 GHORABARI TALUKA 174,088 33,450 GARHO TC 14,177 2725 CHARGE NO 02 14,177 2725 CIRCLE NO 01 6,212 1142 380020101 1,327 280 380020102 897 182 380020103 821 134 380020104 1,269 194 380020105 772 140 380020106 108 25 380020107 719 129 380020108 299 58 CIRCLE NO 02 7,965 1583 380020201 682 159 380020202 502 90 380020203 537 128 380020204 818 168 380020205 1,721 333 380020206 905 185 380020207 2,065 385 380020208 735 135 GHORABARI STC 150,885 28978 BELI TC 26,756 5147 BAN 2,136 333 380010210 2,136 333 BELI 4,494 837 380010201 2,495 435 380010220 1,999 402 DANDHARI 326 66 380010205 326 66 DAULATPUR 1,380 279 380010212 1,380 279 GIRNAR 5,248 1053 380010202 934 167 380010203 2,070 419 380010204 2,244 467 INDO 3,110 624 380010206 803 165 380010207 1,462 286 380010208 845 173 LODHANO 2,114 437 380010218 591 129 380010219 1,523 308 MIRAN PUR 1,389 263 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 380010213 529 102 380010214 860 161 SHAHPUR 3,016 548 380010215 1,300 243 380010216 901 160 380010221 815 145 SUKHPUR 1,453 275 380010209 1,453 275 TAKRO 668 136 380010217 668 136 VIKAR 1,422 296 380010211 1,422 296 GARHO TC 22,344 4350 ADANO 400 80 380010113 400 80 GAMBWAH 440 58 380010110 440 58 GUBA WEST 509 105 380010126 509 105 JARYOON 366 107 380010109 366 107 JHORE PATAR 6,123 1143 380010118 504 98 380010119 1,222 231 380010120 -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa

Working paper Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber- Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth Full Report April 2015 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: F-37109-PAK-1 Reclaiming Prosperity in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa A Medium Term Strategy for Inclusive Growth International Growth Centre, Pakistan Program The International Growth Centre (IGC) aims to promote sustainable growth in developing countries by providing demand-led policy advice informed by frontier research. Based at the London School of Economics and in partnership with Oxford University, the IGC is initiated and funded by DFID. The IGC has 15 country programs. This report has been prepared under the overall supervision of the management team of the IGC Pakistan program: Ijaz Nabi (Country Director), Naved Hamid (Resident Director) and Ali Cheema (Lead Academic). The coordinators for the report were Yasir Khan (IGC Country Economist) and Bilal Siddiqi (Stanford). Shaheen Malik estimated the provincial accounts, Sarah Khan (Columbia) edited the report and Khalid Ikram peer reviewed it. The authors include Anjum Nasim (IDEAS, Revenue Mobilization), Osama Siddique (LUMS, Rule of Law), Turab Hussain and Usman Khan (LUMS, Transport, Industry, Construction and Regional Trade), Sarah Saeed (PSDF, Skills Development), Munir Ahmed (Energy and Mining), Arif Nadeem (PAC, Agriculture and Livestock), Ahsan Rana (LUMS, Agriculture and Livestock), Yasir Khan and Hina Shaikh (IGC, Education and Health), Rashid Amjad (Lahore School of Economics, Remittances), GM Arif (PIDE, Remittances), Najm-ul-Sahr Ata-ullah and Ibrahim Murtaza (R. Ali Development Consultants, Urbanization). For further information please contact [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected] . -

Who Is a Muslim?

4 / Martyr/Mujāhid: Muslim Origins and the Modern Urdu Novel There are two ways to continue the story of the making of a modern lit- er a ture in Urdu a fter the reformist moment of the late nineteenth c entury. The better- known way is to celebrate a rupture from the reformists by writing a history of the All- India Progressive Writer’s Movement (AIPWA), a Bloomsbury- inspired collective that had a tremendous impact on the course of Urdu prose writing. And to be fair, if any single moment DISTRIBUTION— in the modern history of Urdu “lit er a ture” has been able to claim a global circulation (however limited) or express worldly aspirations, it is the well- known moment of the Progressives from within which the stark, rebel voices of Saadat Hasan Manto and Faiz Ahmad Faiz emerged. Founded in 1935–6, the AIPWA was best known for its near revolutionary goals: FOR the desire to create a “new lit er a ture,” which stood directly against the “poetical fancies,” religious orthodoxies, and “love romances with which our periodicals are flooded.”1 Despite its claim to represent all of India, AIPWA was led by a number of Urdu writers— Sajjad Zaheer, Ahmad Ali, among them— who continued, even in the years following Partition in 1947, to have a “disproportionate influence” on the workings and agenda —NOT of the movement.2 The historical and aesthetic successes of the movement, particularly with re spect to Urdu, have gained significant attention from a variety of scholars, including Carlo Coppola, Neetu Khanna, Aamir Mufti, and Geeta Patel, though admittedly more work remains to be done. -

Firms in Aor of Rd Sindh

Appendix-B FIRMS IN AOR OF RD SINDH Ser Name of Firm Chemical RD 1 M/s A.A Industries, Karachi Acetone, MEK, Toluene, Sindh 2 M/s A.J Steel Wire Industries Pvt Ltd, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 3 M/s Aarfeen Traders, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 4 M/s Abbott Laboratories, Karachi Acetone Sindh Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 5 M/s ACI Industrial Chemicals (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Sindh Acid 6 M/s Adamjee Engineering, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 7 M/s Adnan Galvanizig Works, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 8 M/s Agar International, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 9 M/s Ahmed & Sons, Karachi Sindh Acid MEK, Potassium 10 M/s Ahmed Chemical Co, Karachi Permanganate, Acetone & Sindh Hydrochloric Acid 11 M/s Aisha Steel Mills Ltd, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh Hydrochloric Acid & Sulphuric 12 M/s Al Falah Chemical, Karachi Sindh Acid 13 M/s Al Karam Textile Mills (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 14 M/s Al Kausar Chemical Works, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 15 M/s Al Makkah Enterprises Industrial Area, Karachi Sulphuric Acid Sindh 16 M/s Al Noor Metal Industries, Karachi Sulphuric Acid Sindh Toluene, MEK & Hydrochloric 17 M/s Al Rahim Trading Co (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Sindh Acid 18 M/s Ali Murtaza Associate (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Potassium Permanganate Sindh 19 M/s Al-Kausar Chemical Works, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 20 M/s Allied Plastic Industries (Pvt) Ltd, Karachi Toluene & MEK Sindh 21 M/s Almakkah Enterprises, Karachi Hydrochloric Acid Sindh 22 M/s AL-Noor Oil Agency, Karachi Toluene Sindh 23 -

List of Approved Clinical Trial Sites Under the Bio-Study Rules 2017

Government of Pakistan Ministry of National Health Services, Regulations & Coordination DRUG REGULATORY AUTHORITY OF PAKISTAN TF Complex, Sector G-9/4, Islamabad ****** “SAY NO TO CORRUPTION” Updated till: 09th April 2021. LIST OF APPROVED CLINICAL TRIAL SITES UNDER THE BIO-STUDY RULES 2017. S.No License Clinical Trial CTS Address Approved Study Approved Status Remarks Date of . Number Site for Drug. in C.S.C. Expiration Clinical of licence. Trial 01. CTS- M/s Holy Family Gynae Unit-I & II, Holy Women-II Tranexamic 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 17th July 0001 Hospital, Family Hospital, Said Pur Clinical Acid Meeting. 18th July 2019. 2019. Rawalpindi Road. Rawalpindi Studies. Held on 17th July 2019. 02. CTS- M/s Ghouri Plot C-76, Sector 31/5, End-TB, Multi Drug 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 09th October 0002 Clinic, The Indus Opposite Darussalam MDR TB Meeting. 10th October 2019. Hospital, Karachi Society, Korangi Crossing, Clinical Held on 17th 2019. Karachi-75190, Pakistan. Trial July 2019. 03. CTS- Aga Khan Stadium Road, P.O. Box Not Multiple 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 09th October 0003 University 3500, Karachi 74800, Specific Clinical Meeting. 10th October 2022. Hospital, Clinical Pakistan. Trials Held on 17th 2019. Trial Unit (CTU), July 2019. Karachi 04. CTS- Shaukat Khanum 7-A, Khayaban-e-Firdousi, Not Multiple 4th CSC Approved. License issued. 20th 0004 Memorial Cancer Block R3 M.A Johar Town, Specific Clinical Meeting. 21st November November Hospital & Lahore. Trials Held on 17th 2019. 2019. Research Center, July 2019. Lahore. Page 1 of 10 05. CTS- Department of Near Chandni Chowk, Women-II Tranexamic 4th CSC Approved. -

Market Monitor Report

Food Commodities Photo WFP/Aman ur Rehman khan Market Monitor Report WFP VAM | Food Security Analysis Pakistan | November 2020 HIGHLIGHTS • In October 2020, the average retail prices for wheat and wheat flour increased by 5.4% and 3.8%, respectively, while the prices of rice Irri-6 and rice Basmati increased by 0.4% and 0.1%, respectively, when compared to the previous month; • Headline inflation based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased in October 2020 by 1.70% over September 2020 and increased by 8.91% over October 2019; • The prices of staple cereals and non-cereal food commodities in October 2020 experienced negligible to slight fluctuations, except for live chicken and eggs which experienced significant price increases, when compared to the previous month’s prices; • In October 2020, the average ToT slightly decreased by 3.6% from the previous month; • In November 2020, the total global wheat production for 2020/21 is projected at 772.38 million MT, indicating a decrease of 0.7 million MT compared to the projection made in October 2020. Market Monitor | Pakistan | November 2020 Page 2 Headline inflation Headline inflation based on the Consumer Table 1: CPI (%) Price Index (CPI) increased in October Food Non-Food 2020 by 1.70% over September 2020 and Period Urban Rural Urban Rural increased by 8.91% over October 2019. 2020 YoY MoM YoY MoM YoY MoM YoY MoM The food/non-food values of CPI September 12.4 3.0 15.8 3.8 5.0 0.2 7.2 0.3 disaggregated at urban and rural areas is October 13.9 2.8 17.7 4.3 3.6 0.3 5.8 0.5 presented in Table 1.