Theory and Evidence…. Managerial Turnover in Major League Soccer By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019Collegealmanac 8-13-19.Pdf

college soccer almanac Table of Contents Intercollegiate Coaching Records .............................................................................................................................2-5 Intercollegiate Soccer Association of America (ISAA) .......................................................................................6 United Soccer Coaches Rankings Program ...........................................................................................................7 Bill Jeffrey Award...........................................................................................................................................................8-9 United Soccer Coaches Staffs of the Year ..............................................................................................................10-12 United Soccer Coaches Players of the Year ...........................................................................................................13-16 All-Time Team Academic Award Winners ..............................................................................................................17-27 All-Time College Championship Results .................................................................................................................28-30 Intercollegiate Athletic Conferences/Allied Organizations ...............................................................................32-35 All-Time United Soccer Coaches All-Americas .....................................................................................................36-85 -

2021 Record Book 5 Single-Season Records

PROGRAM RECORDS TEAM INDIVIDUAL Game Game Goals .......................................................11 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Goals .................................................. 5, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 ............................................................11 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 Assists ................................................. 4, Damian Silvera vs. UNC, 9/27/92 Assists ......................................................11 vs. Virginia Tech, 9/14/94 ..................................................... 4, Richie Williams vs. VCU, 9/13/89 Points .................................................................... 30 vs. VCU, 9/13/89 ........................................... 4, Kris Kelderman vs. Charleston, 9/10/89 Goals Allowed .................................................12 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 ...........................................4, Chick Cudlip vs. Wash. & Lee, 11/13/62 Margin of Victory ....................................11-0 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Points ................................................ 10, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 Fastest Goal to Start Match .........................................................11-0 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 .................................:09, Alecko Eskandarian vs. American, 10/26/02* Margin of Defeat ..........................................12-0 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 Largest Crowd (Scott) .......................................7,311 vs. Duke, 10/8/88 *Tied for 3rd fastest in an NCAA Soccer Game Largest Crowd (Klöckner) ......................7,906 -

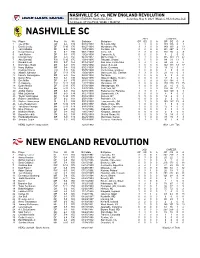

MLS Game Guide

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

2017 United Soccer League Media Guide

Table of Contents LEAGUE ALIGNMENT/IMPORTANT DATES ..............................................................................................4 USL EXECUTIVE BIOS & STAFF ..................................................................................................................6 Bethlehem Steel FC .....................................................................................................................................................................8 Charleston Battery ......................................................................................................................................................................10 Charlotte Independence ............................................................................................................................................................12 Colorado Springs Switchbacks FC .......................................................................................................................................14 FC Cincinnati .................................................................................................................................................................................16 Harrisburg City Islanders ........................................................................................................................................................18 LA Galaxy II ..................................................................................................................................................................................20 -

Burns Mortuary

Page 6C East Oregonian TV TIME SUNDAY Saturday, May 7, 2016 Television > This week’s sports Television > Today’s highlights Saturday WPIX MLB Baseball N.Y. Mets at San Portland at Golden State. (Live) (2:30) Chynoweth Cup. Brandon vs. Seattle. America’s Funniest Diego. (Live) (3:00) 8:30 p.m. (2:30) 6:30 a.m. ROOT Home Videos KFFX 2:00 p.m. MLB Baseball Tampa Bay at 1:00 a.m. (11) DFL Soccer (Live) (2:00) GOLF CHAMPS Golf Final Round Seattle. (3:00) GOLF EPGA Golf Round 1 Mauritius (42) KVEW KATU 7:00 p.m. 7:00 a.m. Insperity Invitational. (Live) (2:00) Open. (2:00) Alfonso Ribeiro hosts as nine fi- USA 10:00 p.m. EPL Soccer (Live) (2:00) 3:00 p.m. TNT NBA Basketball Eastern Conference 3:00 a.m. nalists compete for a $100,000 7:30 a.m. (42) KVEW Triathlon 2015 Island House Semifi nal Game 5 Playof s. Miami at ROOT DFL Soccer B. Munich at prize in this new episode. The GOLF EPGA Golf Round 3 Trophee Invitational. (1:00) Toronto. (2:30) Ingolstadt. (2:00) Hassan II. (2:30) winner will go on to compete 3:30 p.m. Midnight 9:00 a.m. ROOT MLS Soccer San Jose at Seattle. ESPN MLB Baseball Kansas City at N.Y. Friday against the season’s earlier ESPN NCAA Softball Georgia at (2:00) Yankees. (2:00) $100,000 winner for the grand Alabama. (Live) (2:00) 10:00 a.m. 4:00 p.m. -

MLS: Five Things to Watch Post All-Star Game

MLS: Five Things to Watch Post All-Star Game Author : Steven Jotterand Tonight the soccer world turns to Chicago, Illinois. Well, sort of. MLS will field their best against the epic Real Madrid in a glorified exhibition match. This All-Star game signals a transition to the second half of the season. Clubs will begin to turn up the heat as the hunt for the Cup begins. Here are five things to look out for post the All-Star game: LA Galaxy & Orlando City’s Push: In 2016, the Seattle Sounders lost 12 of their first 20 games. Two days after their 12th loss, they sacked Sigi Schmid and hired Brian Schmetzer as interim. One day after naming their new man in charge, Seattle made a splash and signed creative Uruguayan midfielder Nicklas Lodeiro as a Designated Player. A club that was trending nowhere, changed their fortunes around. Within weeks, they were one of the most feared clubs in the league. The Sounders also went on to lift the MLS Cup. 1 / 3 The Galaxy are pretty much exactly in the same position heading into the All-Star Game as Sounders was in 2016. Having lost ten of the first 21 games and sitting in ninth in a weaker Western Conference, the board sacked Curt Onalfo, hired Sigi Schmid, and signed Mexican international attacking midfielder Jonathan dos Santos from Villarreal as a Designated player. Related Post: Orlando City SC: Upstart Lions Stalking and Devouring Their MLS Prey Struggling Orlando City did not sack their manager, but just pulled off the largest trades in MLS history for Dom Dwyer. -

The Best of Soccer Journal: Techniques & Tactics

150 mm 166 mm 166 mm 150 mm Jay Martin (Ed.) The Best of Soccer Journal Journal of Soccer The Best TRAINING EXAMPLE LEARN WHAT TO COACH THE EDITOR The Best of Soccer Journal Warm-up exercises This book offers the experience of the best coaches who have ever Jay Martin, Ph.D. Coaches should be careful during the warm-up phase of practices written for NSCAAs renowned Soccer Journal. Shape your training that players begin with passes that are somewhat shorter than the according to the practical instructions given in this collection. If Techniques + Tactics Martin’s third National length of passes that will occur during the concluding warm-up you want to strengthen the technique and tactics of your team on Coach of the Year award activities. Be certain that your players are warmed up properly and the field, the given training plans will easily provide you with the caps a fairy-tale ending to are stretched sufficiently to prevent injury. knowledge to improve the skills of you players. · the 2011 season. Not only Techniques + Tactics Techniques did his Bishops win their sec- Exercise 1 Based in Kansas City, KS., the NSCAA is the largest soccer coaches’ ond NCAA national title, but Short, short, long passing in groups of five. Begin with players in a organization in the world. Since its founding in 1941, it has grown the victory in the champion- 30 x 30-yard space and expand as needed (Diagram # 1). Player to include more than 30,000 members who coach both genders at ship game gave Martin his receiving the long pass should take a controlling touch and dribble all levels of the sport. -

Ucla World Cup Players 2006

UCLA’S NATIONAL TEAM CONNECTION Snitko competed for the United States in Atlanta, and the 1992 Olympic team UCLA WORLD CUP PLAYERS 2006 ........Carlos Bocanegra included six former Bruins ̶ Friedel, ........................Jimmy Conrad Henderson, Jones, Lapper, Moore and ............................ Eddie Lewis Zak Ibsen ̶ on its roster, the most .............Frankie Hejduk (inj.) from any collegiate institution. Other 2002 ..................Brad Friedel UCLA Olympians include Caligiuri, ...................... Frankie Hejduk .............................. Cobi Jones Krumpe and Vanole (1988) and Jeff ............................ Eddie Lewis Hooker (1984). ......................Joe-Max Moore Several Bruins were instrumental to 1998 ..................Brad Friedel ...................... Frankie Hejduk the United States’ gold medal win .............................. Cobi Jones at the 1991 Pan American Games. ......................Joe-Max Moore Friedel tended goal for the U.S., while 1994 ................Paul Caligiuri Moore nailed the game-winning goal ............................Brad Friedel in overtime in the gold-medal match .............................. Cobi Jones against Mexico. Jones scored one goal ........................... Mike Lapper ......................Joe-Max Moore Bruins Pete Vagenas, Ryan Futagaki, Carlos Bocanegra, Sasha and an assist against Canada. A Bruin- Victorine and Steve Shak (clockwise from top left) won bronze 1990 ................Paul Caligiuri dominated U.S. team won a bronze medals for the U.S. at the 1999 Pan -

Congressional Record—Senate S1366

S1366 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE January 23, 1995 family, and then business—and busi- Cup team and then professionally in Ger- Matt Laughlin, midfielder, Fairfax ness is way down on the list.’’ His con- many. Station, VA. cern for people dictates his outlook on Indiana, on the other hand, had eight sen- Matt Leanard, forward, Fairfax Sta- iors who were hungry for a title after falling business. He is a big believer in hard short of expectations in previous years. Its tion, VA. work, and his pet peeves are a wrong midfield also was rated as the nation’s best Christian Nix, midfielder, Fairfax, order and an unclean facility. But on [with two All Americans]. But none of that VA. the opposite side, his favorite way of seemed to matter once the game started. Clint Peay, defender, Columbia, MD. dealing with employees is to find a way I was fortunate to attend the NCAA Mark Peters, goalkeeper, Winchester, to compliment them. championship played at Davidson Uni- VA. Jerry is also known for his love of versity in North Carolina. I can report Brandon Pollard, defender, Rich- children—other people’s as well as his without equivocation that the UVA mond, VA. own. Locally, he is what you might call Cavaliers showed grit, determination, Key Reid, midfielder, Searchlight, the pied piper of hamburgers. He al- and heart as they successfully defended NV. ways carries coupons for free burgers their NCAA championship. Each team Yuri Sagatov, goalkeeper, Fairfax, in his back pocket and passes them out member displayed courage time and VA. to children wherever he sees them. -

Croatia Vs England Full Game Torrent Download World Cup Full Matches

croatia vs england full game torrent download World Cup full matches. Footballia is the first free interactive football video library where you can watch full football matches for free anytime, anywhere. Thank you! First of all, we’d like to tell you how grateful we are to all of you who stuck by us during our offline period. Thank you so much! Keep Footballia alive! But the threat is not gone. As you know, in recent months, Footballia has been in danger of disappearing. We’ve improved our protection so you can keep enjoying football history, but as a consequence, our expenses have increased. How can you help? Many of you have asked how you can help the project. The best way is to subscribe to Footballia Master. Not only will you make the project stronger, but you’ll get a bunch of cool features in return! Randomizer. You don't know which match to watch today among more than 20,000 available on Footballia? Footballia Randomizer is a new tool that will take you to a random match of the Footballia catalogue. World Cup full matches. Footballia is the first free interactive football video library where you can watch full football matches for free anytime, anywhere. Thank you! First of all, we’d like to tell you how grateful we are to all of you who stuck by us during our offline period. Thank you so much! Keep Footballia alive! But the threat is not gone. As you know, in recent months, Footballia has been in danger of disappearing. -

The Marquee Effect : a Study of the Effect of Designated Players On

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 2016 The aM rquee effect : a study of the effect of designated players on revenue and performance in major league soccer Hannah Holub Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Economics Commons Recommended Citation Holub, Hannah, "The aM rquee effect : a study of the effect of designated players on revenue and performance in major league soccer" (2016). Honors Theses. Paper 849. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Marquee Effect: A Study of the Effect of Designated Players on Revenue and Performance in Major League Soccer by Hannah Holub Honors Thesis Submitted to Department of Economics University of Richmond Richmond, VA April 28, 2016 Advisor: Dr. Jim Monks 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Literature Review 7 III. Theoretical Model 12 IV. Econometric Models and Methods 16 V. Data 22 VI. Results 23 VII. Robustness 28 VIII. Conclusion 31 IX. Appendix 34 X. References 50 2 Introduction Since its formation in 1994 Major League Soccer (MLS) has slowly been gaining the momentum to reach a level of recognition similar to that of the top four sports leagues in the United States – the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League, and Major League Baseball. Major League Soccer (MLS) is the top tier professional soccer league in the United States, one of only two leagues to reach that status and the only soccer league to sustain long term success.1 Made up of nineteen teams across the United States and Canada, the MLS is structured much differently than the other leagues both within the United States and internationally. -

ESPN Deportes Soccer One Sheet 11-9

Reaches Hispanic Sports Fans WHEREVER THEY ARE ESPN Deportes is the only 24/7 Spanish language network dedicated to 100% sports programming. A multimedia brand that celebrates the Hispanic fan and the sports they are passionate about; ESPN Deportes properties engage fans with original content and top programming. DISTRIBUTION UNMATCHED • 4 million US Hispanic homes and growing MULTIMEDIA – 5 million homes by end of 2008 ASSETS: • Available in every U.S. market FANS • 84% of Spanish-speaking Hispanics consider themselves sports fans • Twice as likely to be loyal to sporting event sponsors1 • Hispanic males spend nearly one hour with ESPN media every day2 CONTENT QUALITY • 70% original programming • 8 of the top 10 sports on TV for Spanish speakers – Mexican League Soccer – NASCAR – MLB – NBA – Action Sports – MLS – NFL – UEFA Champions League • Award-winning studio shows – SportsCenter – Cronometro – Primera Plana – NFL Esta Noche – Perfiles – Beisbol Esta Noche 1. Hispanic Sports Poll; 2. Knowledge Networks/SRI ESPN All Day, Everyday, Fall 2006 Soccer Coverage SCORES BIG WITH FANS YEAR ROUND MEXICAN LEAGUE ESPN Deportes will air LIVE Mexican League Soccer games every matchdate over the Apertura and Clausura seasons, totaling 34 games. In the Apertura (August – November) there will be 11 primetime Friday games, two primetime Wednesday games and four games on Saturday afternoon. The Friday game is the only game played that day, and both the Wednesday and Friday games will most likely air ONLY on Deportes in the US. UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE UEFA (Union of European Football Associations) is the governing body for Soccer throughout Europe. The Champions League is the most prestigious club championship on the continent, only 32 top-ranked teams across all the biggest European Leagues qualify.