Ethnic Mexicans and the Mexico-Us Soccer Rivalry, 1990-2002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SMC Security Probes Assaults by EMILY WILLETT Normal Build, Dark Hair and Saint Mary’S Editor Approximately Six Feet Tall

# — Saint Mary’s College The Observer NOTRE DAME « INDIANA VOL. XXIV NO. 15 FRIDAY , SEPTEMBER 13, 1991 THE INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER SERVING NOTRE DAME AND SAINT MARY’S SMC Security probes assaults By EMILY WILLETT normal build, dark hair and Saint Mary’s Editor approximately six feet tall. Security conducted an inves Saint Mary’s Security is in tigation of the area which was vestigating the assault of a to no avail. Saint Mary’s student which took This incident is the second place at approximately 8:30 reported attack on campus this p.m. Wednesday night on the week. On Monday evening campus. Security responded to a The victim reported that she reported assault on the was walking from her car in the walkway between McCandless Angela Athletic Facility parking Hall and the Cushwa-Leighton lot on the walkway which runs Library. While both cases are beside the building when the still under investigation, at this attacker approached her from time the two incidents are behind. believed to be unrelated. The victim said that the as “We do not have enough con sailant covered her mouth with crete evidence at this time to his hand and attempted to drag show that the incidents are as her toward a nearby tree. The sociated,” said Richard Chle- victim said she freed herself bek, Director of Safety and Se The Observer/Andrew McCloskey from the attacker, slashing his curity. Football fanatics face with her keys, and ran to Saint Mary’s Security will be McCandless Hall. increasing security presence in Football fans of all kinds came together last Saturday to show their support for the Notre Dame She described the attacker to the areas of the two attacks, football team. -

2019Collegealmanac 8-13-19.Pdf

college soccer almanac Table of Contents Intercollegiate Coaching Records .............................................................................................................................2-5 Intercollegiate Soccer Association of America (ISAA) .......................................................................................6 United Soccer Coaches Rankings Program ...........................................................................................................7 Bill Jeffrey Award...........................................................................................................................................................8-9 United Soccer Coaches Staffs of the Year ..............................................................................................................10-12 United Soccer Coaches Players of the Year ...........................................................................................................13-16 All-Time Team Academic Award Winners ..............................................................................................................17-27 All-Time College Championship Results .................................................................................................................28-30 Intercollegiate Athletic Conferences/Allied Organizations ...............................................................................32-35 All-Time United Soccer Coaches All-Americas .....................................................................................................36-85 -

2021 Record Book 5 Single-Season Records

PROGRAM RECORDS TEAM INDIVIDUAL Game Game Goals .......................................................11 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Goals .................................................. 5, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 ............................................................11 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 Assists ................................................. 4, Damian Silvera vs. UNC, 9/27/92 Assists ......................................................11 vs. Virginia Tech, 9/14/94 ..................................................... 4, Richie Williams vs. VCU, 9/13/89 Points .................................................................... 30 vs. VCU, 9/13/89 ........................................... 4, Kris Kelderman vs. Charleston, 9/10/89 Goals Allowed .................................................12 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 ...........................................4, Chick Cudlip vs. Wash. & Lee, 11/13/62 Margin of Victory ....................................11-0 vs. Old Dominion, 10/1/71 Points ................................................ 10, Bill Hodill vs. Davidson, 10/17/42 Fastest Goal to Start Match .........................................................11-0 vs. Richmond, 10/20/81 .................................:09, Alecko Eskandarian vs. American, 10/26/02* Margin of Defeat ..........................................12-0 vs. Maryland, 10/8/41 Largest Crowd (Scott) .......................................7,311 vs. Duke, 10/8/88 *Tied for 3rd fastest in an NCAA Soccer Game Largest Crowd (Klöckner) ......................7,906 -

Major League Soccer-Historie a Současnost Bakalářská Práce

MASARYKOVA UNIVERZITA Fakulta sportovních studií Katedra sportovních her Major League Soccer-historie a současnost Bakalářská práce Vedoucí bakalářské práce: Vypracoval: Mgr. Pavel Vacenovský Zdeněk Bezděk TVS/Trenérství Brno, 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a na základě literatury a pramenů uvedených v použitých zdrojích. V Brně dne 24. května 2013 podpis Děkuji vedoucímu bakalářské práce Mgr. Pavlu Vacenovskému, za podnětné rady, metodické vedení a připomínky k této práci. Úvod ........................................................................................................................ 6 1. FOTBAL V USA PŘED VZNIKEM MLS .................................................. 8 2. PŘÍPRAVA NA ÚVODNÍ SEZÓNU MLS ............................................... 11 2.1. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 17. října 1995..................................... 12 2.2. Tisková konference MLS ze dne 18. října 1995..................................... 14 2.3. První sponzoři MLS ............................................................................... 15 2.4. Platy Marquee players ............................................................................ 15 2.5. Další události v roce 1995 ...................................................................... 15 2.6. Drafty MLS ............................................................................................ 16 2.6.1. 1996 MLS College Draft ................................................................. 17 2.6.2. 1996 MLS Supplemental Draft ...................................................... -

MLS Game Guide

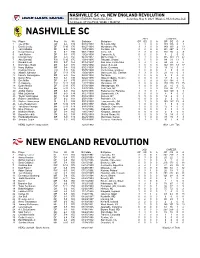

NASHVILLE SC vs. NEW ENGLAND REVOLUTION NISSAN STADIUM, Nashville, Tenn. Saturday, May 8, 2021 (Week 4, MLS Game #44) 12:30 p.m. CT (MyTV30; WSBK / MyRITV) NASHVILLE SC 2021 CAREER No. Player Pos Ht Wt Birthdate Birthplace GP GS G A GP GS G A 1 Joe Willis GK 6-5 189 08/10/1988 St. Louis, MO 3 3 0 0 139 136 0 1 2 Daniel Lovitz DF 5-10 170 08/27/1991 Wyndmoor, PA 3 3 0 0 149 113 2 13 3 Jalil Anibaba DF 6-0 185 10/19/1988 Fontana, CA 0 0 0 0 231 207 6 14 4 David Romney DF 6-2 190 06/12/1993 Irvine, CA 3 3 0 0 110 95 4 8 5 Jack Maher DF 6-3 175 10/28/1999 Caseyville, IL 0 0 0 0 3 2 0 0 6 Dax McCarty MF 5-9 150 04/30/1987 Winter Park, FL 3 3 0 0 385 353 21 62 7 Abu Danladi FW 5-10 170 10/18/1995 Takoradi, Ghana 0 0 0 0 84 31 13 7 8 Randall Leal FW 5-7 163 01/14/1997 San Jose, Costa Rica 3 3 1 2 24 22 4 6 9 Dominique Badji MF 6-0 170 10/16/1992 Dakar, Senegal 1 0 0 0 142 113 33 17 10 Hany Mukhtar MF 5-8 159 03/21/1995 Berlin, Germany 3 3 1 0 18 16 5 4 11 Rodrigo Pineiro FW 5-9 146 05/05/1999 Montevideo, Uruguay 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 12 Alistair Johnston DF 5-11 170 10/08/1998 Vancouver, BC, Canada 3 3 0 0 21 18 0 1 13 Irakoze Donasiyano MF 5-9 155 02/03/1998 Tanzania 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 14 Daniel Rios FW 6-1 185 02/22/1995 Miguel Hidalgo, Mexico 0 0 0 0 18 8 4 0 15 Eric Miller DF 6-1 175 01/15/1993 Woodbury, MN 0 0 0 0 121 104 0 3 17 CJ Sapong FW 5-11 185 12/27/1988 Manassas, VA 3 0 0 0 279 210 71 25 18 Dylan Nealis DF 5-11 175 07/30/1998 Massapequa, NY 1 0 0 0 20 10 0 0 19 Alex Muyl MF 5-11 175 09/30/1995 New York, NY 3 2 0 0 134 86 11 20 20 Anibal -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

Fox Sports Highlights – 3 Things You Need to Know

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Wednesday, Sept. 17, 2014 FOX SPORTS HIGHLIGHTS – 3 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW NFL: Philadelphia Hosts Washington and Dallas Meets St. Louis in Regionalized Matchups COLLEGE FOOTBALL: No. 4 Oklahoma Faces West Virginia in Big 12 Showdown on FOX MLB: AL Central Battle Between Tigers and Royals, Plus Dodgers vs. Cubs in FOX Saturday Baseball ******************************************************************************************************* NFL DIVISIONAL MATCHUPS HIGHLIGHT WEEK 3 OF THE NFL ON FOX The NFL on FOX continues this week with five regionalized matchups across the country, highlighted by three divisional matchups, as the Philadelphia Eagles host the Washington Redskins, the Detroit Lions welcome the Green Bay Packers, and the San Francisco 49ers play at the Arizona Cardinals. Other action this week includes the Dallas Cowboys at St. Louis Rams and Minnesota Vikings at New Orleans Saints. FOX Sports’ NFL coverage begins each Sunday on FOX Sports 1 with FOX NFL KICKOFF at 11:00 AM ET with host Joel Klatt and analysts Donovan McNabb and Randy Moss. On the FOX broadcast network, FOX NFL SUNDAY immediately follows FOX NFL KICKOFF at 12:00 PM ET with co-hosts Terry Bradshaw and Curt Menefee alongside analysts Howie Long, Michael Strahan, Jimmy Johnson, insider Jay Glazer and rules analyst Mike Pereira. SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 21 GAME PLAY-BY-PLAY/ANALYST/SIDELINE COV. TIME (ET) Washington Redskins at Philadelphia Eagles Joe Buck, Troy Aikman 24% 1:00PM & Erin Andrews Lincoln Financial Field – Philadelphia, Pa. MARKETS INCLUDE: Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Washington, Miami, Raleigh, Charlotte, Hartford, Greenville, West Palm Beach, Norfolk, Greensboro, Richmond, Knoxville Green Bay Packers at Detroit Lions Kevin Burkhardt, John Lynch 22% 1:00PM & Pam Oliver Ford Field – Detroit, Mich. -

Algunos Aspectos Prácticos Del Litigio Internacional En Los Tribunales De La Florida Angel Castillo Jr

University of Miami Law School University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 4-1-1985 Algunos Aspectos Prácticos del Litigio Internacional en los Tribunales de la Florida Angel Castillo Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Angel Castillo Jr., Algunos Aspectos Prácticos del Litigio Internacional en los Tribunales de la Florida, 16 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 559 (1985) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol16/iss3/5 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter-American Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REPORTS ALGUNOS ASPECTOS PRACTICOS DEL LITIGIO INTERNACIONAL EN LOS TRIBUNALES DE LA FLORIDA*t ANGEL CASTILLO, JR.** I. QUItN PUEDE LITIGAR EN LOS TRIBUNALES DE LA FLORIDA 560 II. ABOGADOS; GASTOS Y COSTAS 561 III. JURISDICCI6N DE LOS TRIBUNALES DE LA FLORIDA SOBRE LAS PERSONAS EXTRANJERAS NO RESIDENTES EN LA FLORIDA 562 A. Jurisdicci6n voluntaria 562 B. Jurisdicci6n involuntaria 563 IV. EL EMPLAZAMIENTO DE LA DEMANDA 567 A. Por entrega al Secretario de Estado de la Florida 568 * Este reporte fue presentado en la Cuarta Conferencia Para Abogados de las Americas, patrocinado por la Asociaci6n de Abogados Cubano-Americanos en conjunto con El Centro de Leyes de la Universidad de Miami el 18 de julio de 1984. -

March 17Th 1999

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Inland Empire Hispanic News Special Collections & University Archives 3-17-1999 March 17th 1999 Hispanic News Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/hispanicnews Recommended Citation Hispanic News, "March 17th 1999" (1999). Inland Empire Hispanic News. 226. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/hispanicnews/226 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections & University Archives at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inland Empire Hispanic News by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. / t -i ' f .t '-•A- ' •> •••<t- •*' • - • • -- The Sinfonia Mexicana Society and the Inland Empire Symphony Association present Qrquesta Sinfonica Naciona! de Mexico, Sunday Apr. 11 - Call 381-5388 ^4 r-¥- A Wfl .s . —' f'•: y.-.-. -i-rr.u J - '• -y--.>.'V. -s- • A Publication of the Hispanic Communication & Deveiopment Corporation Wednesday w INLAND EMPIRt my T'^ March 17,1999 Volume 12 ^I^Number 14 HISPANIC NEWS Serving the Hispanic Communities in the Inland Empire San Bernardino • Coiton • Riaito • Bloomington . Redlands • Fontana • Rancho Cucamonga • Ontario • Victor Vaiiey • Riverside • Casa Bianca • Corona The Intend Empire s Only Hispenic Minority Owned English Languege Newspaper The Inland Empire Hispanic News salutes six representative women for National Womens Recognition Month ' h • < * Mmmtm March is designated as Women's School Leadership Academy, Middle Recognition Month. During the School Collaborative Network and Cali month, professionals and volunteers fornia Quality Program Review; Middle are recognized for their role in the School Task Force, San Diego Office betterment of their respective commu of Education; trainer-California Qual nities in areas of social, economic, ity Program Review, e valuator- Elemen health or welfare. -

Ucla World Cup Players 2006

UCLA’S NATIONAL TEAM CONNECTION Snitko competed for the United States in Atlanta, and the 1992 Olympic team UCLA WORLD CUP PLAYERS 2006 ........Carlos Bocanegra included six former Bruins ̶ Friedel, ........................Jimmy Conrad Henderson, Jones, Lapper, Moore and ............................ Eddie Lewis Zak Ibsen ̶ on its roster, the most .............Frankie Hejduk (inj.) from any collegiate institution. Other 2002 ..................Brad Friedel UCLA Olympians include Caligiuri, ...................... Frankie Hejduk .............................. Cobi Jones Krumpe and Vanole (1988) and Jeff ............................ Eddie Lewis Hooker (1984). ......................Joe-Max Moore Several Bruins were instrumental to 1998 ..................Brad Friedel ...................... Frankie Hejduk the United States’ gold medal win .............................. Cobi Jones at the 1991 Pan American Games. ......................Joe-Max Moore Friedel tended goal for the U.S., while 1994 ................Paul Caligiuri Moore nailed the game-winning goal ............................Brad Friedel in overtime in the gold-medal match .............................. Cobi Jones against Mexico. Jones scored one goal ........................... Mike Lapper ......................Joe-Max Moore Bruins Pete Vagenas, Ryan Futagaki, Carlos Bocanegra, Sasha and an assist against Canada. A Bruin- Victorine and Steve Shak (clockwise from top left) won bronze 1990 ................Paul Caligiuri dominated U.S. team won a bronze medals for the U.S. at the 1999 Pan -

Panini World Cup 2006

soccercardindex.com Panini World Cup 2006 World Cup 2006 53 Cafu Ghana Poland 1 Official Emblem 54 Lucio 110 Samuel Kuffour 162 Kamil Kosowski 2 FIFA World Cup Trophy 55 Roque Junior 111 Michael Essien (MET) 163 Maciej Zurawski 112 Stephen Appiah 3 Official Mascot 56 Roberto Carlos Portugal 4 Official Poster 57 Emerson Switzerland 164 Ricardo Carvalho 58 Ze Roberto 113 Johann Vogel 165 Maniche Team Card 59 Kaka (MET) 114 Alexander Frei 166 Luis Figo (MET) 5 Angola 60 Ronaldinho (MET) 167 Deco 6 Argentina 61 Adriano Croatia 168 Pauleta 7 Australia 62 Ronaldo (MET) 115 Robert Kovac 169 Cristiano Ronaldo 116 Dario Simic 8 Brazil 117 Dado Prso Saudi Arabia Czech Republic 9 Czech Republic 170 Yasser Al Qahtani 63 Petr Cech (MET) 10 Costa Rica Iran 171 Sami Al Jaber 64 Tomas Ujfalusi 11 Ivory Coast 118 Ali Karimi 65 Marek Jankulovski 12 Germany 119 Ali Daei Serbia 66 Tomas Rosicky 172 Dejan Stankovic 13 Ecuador 67 Pavel Nedved Italy 173 Savo Milosevic 14 England 68 Karel Poborsky 120 Gianluigi Buffon (MET) 174 Mateja Kezman 15 Spain 69 Milan Baros 121 Gianluca Zambrotta 16 France 122 Fabio Cannavaro Sweden Costa Rica 17 Ghana 123 Alessandro Nesta 175 Freddy Ljungberg 70 Walter Centeno 18 Switzerland 124 Mauro Camoranesi 176 Christian Wilhelmsso 71 Paulo Wanchope 125 Gennaro Gattuso 177 Zlatan Ibrahimovic 19 Croatia 126 Andrea Pirlo 20 Iran Ivory Coast 127 Francesco Totti (MET) Togo 21 Italy 72 Kolo Toure 128 Alberto Gilardino 178 Mohamed Kader 22 Japan 73 Bonaventure -

Congressional Record—Senate S1366

S1366 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE January 23, 1995 family, and then business—and busi- Cup team and then professionally in Ger- Matt Laughlin, midfielder, Fairfax ness is way down on the list.’’ His con- many. Station, VA. cern for people dictates his outlook on Indiana, on the other hand, had eight sen- Matt Leanard, forward, Fairfax Sta- iors who were hungry for a title after falling business. He is a big believer in hard short of expectations in previous years. Its tion, VA. work, and his pet peeves are a wrong midfield also was rated as the nation’s best Christian Nix, midfielder, Fairfax, order and an unclean facility. But on [with two All Americans]. But none of that VA. the opposite side, his favorite way of seemed to matter once the game started. Clint Peay, defender, Columbia, MD. dealing with employees is to find a way I was fortunate to attend the NCAA Mark Peters, goalkeeper, Winchester, to compliment them. championship played at Davidson Uni- VA. Jerry is also known for his love of versity in North Carolina. I can report Brandon Pollard, defender, Rich- children—other people’s as well as his without equivocation that the UVA mond, VA. own. Locally, he is what you might call Cavaliers showed grit, determination, Key Reid, midfielder, Searchlight, the pied piper of hamburgers. He al- and heart as they successfully defended NV. ways carries coupons for free burgers their NCAA championship. Each team Yuri Sagatov, goalkeeper, Fairfax, in his back pocket and passes them out member displayed courage time and VA. to children wherever he sees them.