New Mexico Butterflies: Checklist, Distribution and Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insects of Western North America 4. Survey of Selected Insect Taxa of Fort Sill, Comanche County, Oklahoma 2

Insects of Western North America 4. Survey of Selected Insect Taxa of Fort Sill, Comanche County, Oklahoma 2. Dragonflies (Odonata), Stoneflies (Plecoptera) and selected Moths (Lepidoptera) Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Survey of Selected Insect Taxa of Fort Sill, Comanche County, Oklahoma 2. Dragonflies (Odonata), Stoneflies (Plecoptera) and selected Moths (Lepidoptera) by Boris C. Kondratieff, Paul A. Opler, Matthew C. Garhart, and Jason P. Schmidt C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 March 15, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration (top to bottom): Widow Skimmer (Libellula luctuosa) [photo ©Robert Behrstock], Stonefly (Perlesta species) [photo © David H. Funk, White- lined Sphinx (Hyles lineata) [photo © Matthew C. Garhart] ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado 80523 Copyrighted 2004 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………………………….…1 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………..…………………………………………….…3 OBJECTIVE………………………………………………………………………………………….………5 Site Descriptions………………………………………….. METHODS AND MATERIALS…………………………………………………………………………….5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION………………………………………………………………………..…...11 Dragonflies………………………………………………………………………………….……..11 -

Phylogenetic Relationships and Historical Biogeography of Tribes and Genera in the Subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae)

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKBIJBiological Journal of the Linnean Society 0024-4066The Linnean Society of London, 2005? 2005 862 227251 Original Article PHYLOGENY OF NYMPHALINAE N. WAHLBERG ET AL Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2005, 86, 227–251. With 5 figures . Phylogenetic relationships and historical biogeography of tribes and genera in the subfamily Nymphalinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) NIKLAS WAHLBERG1*, ANDREW V. Z. BROWER2 and SÖREN NYLIN1 1Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Zoology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon 97331–2907, USA Received 10 January 2004; accepted for publication 12 November 2004 We infer for the first time the phylogenetic relationships of genera and tribes in the ecologically and evolutionarily well-studied subfamily Nymphalinae using DNA sequence data from three genes: 1450 bp of cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) (in the mitochondrial genome), 1077 bp of elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1-a) and 400–403 bp of wing- less (both in the nuclear genome). We explore the influence of each gene region on the support given to each node of the most parsimonious tree derived from a combined analysis of all three genes using Partitioned Bremer Support. We also explore the influence of assuming equal weights for all characters in the combined analysis by investigating the stability of clades to different transition/transversion weighting schemes. We find many strongly supported and stable clades in the Nymphalinae. We are also able to identify ‘rogue’ -

List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017

Washington Natural Heritage Program List of Animal Species with Ranks October 2017 The following list of animals known from Washington is complete for resident and transient vertebrates and several groups of invertebrates, including odonates, branchipods, tiger beetles, butterflies, gastropods, freshwater bivalves and bumble bees. Some species from other groups are included, especially where there are conservation concerns. Among these are the Palouse giant earthworm, a few moths and some of our mayflies and grasshoppers. Currently 857 vertebrate and 1,100 invertebrate taxa are included. Conservation status, in the form of range-wide, national and state ranks are assigned to each taxon. Information on species range and distribution, number of individuals, population trends and threats is collected into a ranking form, analyzed, and used to assign ranks. Ranks are updated periodically, as new information is collected. We welcome new information for any species on our list. Common Name Scientific Name Class Global Rank State Rank State Status Federal Status Northwestern Salamander Ambystoma gracile Amphibia G5 S5 Long-toed Salamander Ambystoma macrodactylum Amphibia G5 S5 Tiger Salamander Ambystoma tigrinum Amphibia G5 S3 Ensatina Ensatina eschscholtzii Amphibia G5 S5 Dunn's Salamander Plethodon dunni Amphibia G4 S3 C Larch Mountain Salamander Plethodon larselli Amphibia G3 S3 S Van Dyke's Salamander Plethodon vandykei Amphibia G3 S3 C Western Red-backed Salamander Plethodon vehiculum Amphibia G5 S5 Rough-skinned Newt Taricha granulosa -

Environmental Impact Assessment

JANUARY 2010 ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED LAND & HOUSING SUBDIVISION AT HOLLAND ESTATE, MARTHA BRAE TRELAWNY [Prepared for KENCASA Project Management & Construction Limited] CONRAD DOUGLAS & ASSOCIATES LIMITED 14 Carvalho Drive Kingston 10 Jamaica W.I. Telephone: 929-0023/0025/8824 Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Website: www.cda-estech.com ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A LAND AND HOUSING SUBDIVISION AT HOLLAND ESTATE, MARTHA BRAE, TRELAWNY Rev. 01 Prepared for: KENCASA Construction and Project Management Limited Conrad Douglas & Associates LTD CD*PRJ 1091/09 Holland Estate Housing Subdivision EIA – KENCASA PROPRIETARY RESTRICTION NOTICE This document contains information proprietary to Conrad Douglas & Associates Limited (CD&A) and KENCASA Construction and Project Management Limited and shall not be reproduced or transferred to other documents, or disclosed to others, or used for any purpose other than that for which it is furnished without the prior written permission of CD&A. Further, this Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is the sole property of CD&A and KENCASA Construction and Project Management Limited and no portion of it shall be used in the formulation of now or in the future, by the agencies and/or persons who may see it in the process of its review, without written permission of CD&A and KENCASA Construction and Project Management Limited. Conrad Douglas & Associates Ltd. CD*PRJ 1091/09 Holland Estate Housing Subdivision -

Lodgepole Pine Dwarf Mistletoe in Taylor Park, Colorado Report for the Taylor Park Environmental Assessment

Lodgepole Pine Dwarf Mistletoe in Taylor Park, Colorado Report for the Taylor Park Environmental Assessment Jim Worrall, Ph.D. Gunnison Service Center Forest Health Protection Rocky Mountain Region USDA Forest Service 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 2. DESCRIPTION, DISTRIBUTION, HOSTS ..................................................................................... 2 3. LIFE CYCLE....................................................................................................................................... 3 4. SCOPE OF TREATMENTS RELATIVE TO INFESTED AREA ................................................. 4 5. IMPACTS ON TREES AND FORESTS ........................................................................................... 4 5.1 TREE GROWTH AND LONGEVITY .................................................................................................... 4 5.2 EFFECTS OF DWARF MISTLETOE ON FOREST DYNAMICS ............................................................... 6 5.3 RATE OF SPREAD AND INTENSIFICATION ........................................................................................ 6 6. IMPACTS OF DWARF MISTLETOES ON ANIMALS ................................................................ 6 6.1 DIVERSITY AND ABUNDANCE OF VERTEBRATES ............................................................................ 7 6.2 EFFECT OF MISTLETOE-CAUSED SNAGS ON VERTEBRATES ............................................................12 -

INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a Synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a Historical Sketch

ZOOLOGÍA-TAXONOMÍA www.unal.edu.co/icn/publicaciones/caldasia.htm Caldasia 31(2):407-440. 2009 HACIA UNA SÍNTESIS DE LOS PAPILIONOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a historical sketch JOSÉ LUIS SALINAS-GUTIÉRREZ El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] CLAUDIO MÉNDEZ Escuela de Biología, Universidad de San Carlos, Ciudad Universitaria, Campus Central USAC, Zona 12. Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] MERCEDES BARRIOS Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (CECON), Universidad de San Carlos, Avenida La Reforma 0-53, Zona 10, Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] CARMEN POZO El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] JORGE LLORENTE-BOUSQUETS Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. Apartado Postal 70-399, México D.F. 04510; México. [email protected]. Autor responsable. RESUMEN La riqueza biológica de Mesoamérica es enorme. Dentro de esta gran área geográfi ca se encuentran algunos de los ecosistemas más diversos del planeta (selvas tropicales), así como varios de los principales centros de endemismo en el mundo (bosques nublados). Países como Guatemala, en esta gran área biogeográfi ca, tiene grandes zonas de bosque húmedo tropical y bosque mesófi lo, por esta razón es muy importante para analizar la diversidad en la región. Lamentablemente, la fauna de mariposas de Guatemala es poco conocida y por lo tanto, es necesario llevar a cabo un estudio y análisis de la composición y la diversidad de las mariposas (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) en Guatemala. -

BULLETIN of the ALLYN MUSEUM 3621 Bayshore Rd

BULLETIN OF THE ALLYN MUSEUM 3621 Bayshore Rd. Sarasota, Florida 33580 Published By The Florida State Museum University of Florida Gainesville. Florida 32611 Number 107 30 December 1986 A REVIEW OF THE SATYRINE GENUS NEOMINOIS, WITH DESCRIPriONS OF THREE NEW SUBSPECIES George T. Austin Nevada State Museum and Historical Society 700 Twin Lakes Drive, Las Vegas, Nevada 89107 In recent years, revisions of several genera of satyrine butterflies have been undertaken (e. g., Miller 1972, 1974, 1976, 19781. To this, I wish to add a revision of the genus Neominois. Neominois Scudder TYPE SPECIES: Satyrus ridingsii W. H. Edwards by original designation (Scudder 1875b, p. 2411 Satyrus W. H. Edwards (1865, p. 2011, Rea.kirt (1866, p. 1451, W. H. Edwards (1872, p. 251, Strecker (1873, p. 291, W. H. Edwards (1874b, p. 261, W. H. Edwards (1874c, p. 5421, Mead (1875, p. 7741, W. H. Edwards (1875, p. 7931, Scudder (1875a, p. 871, Strecker (1878a, p. 1291, Strecker (1878b, p. 1561, Brown (1964, p. 3551 Chionobas W. H. Edwards (1870, p. 1921, W. H. Edwards (1872, p. 271, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, W. H. Edwards (1874b, p. 281, Brown (1964, p. 3571 Hipparchia Kirby (1871, p. 891, W. H. Edwards (1877, p. 351, Kirby (1877, p. 7051, Brooklyn Ent. Soc. (1881, p. 31, W. H. Edwards (1884, p. [7)l, Maynard (1891, p. 1151, Cockerell (1893, p. 3541, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, Hanham (1900, p. 3661 Neominois Scudder (1875b, p. 2411, Strecker (1876, p. 1181, Scudder (1878, p. 2541, Elwes and Edwards (1893, p. 4591, W. -

Courtship and Oviposition Patterns of Two Agathymus (Megathymidae)

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 39(3). 1985. 171-176 COURTSHIP AND OVIPOSITION PATTERNS OF TWO AGATHYMUS (MEGATHYMIDAE) DON B. STALLINGS AND VIOLA N. T. STALLINGS P.O. Box 106, 616 W. Central, Caldwell, Kansas 67022 AND J. R. TURNER AND BEULAH R. TURNER 2 South Boyd, Caldwell, Kansas 67022 ABSTRACT. Males of Agathymus estelleae take courtship sentry positions near ten eral virgin females long before the females are ready to mate. Males of Agathymus mariae are territorial and pursue virgin females that approach their territories. Ovipo sition patterns of the two species are very similar. Females alight on or near the plants to oviposit and do not drop ova in flight. Few detailed observations of the courtship and oviposition of the skipper butterflies in natural environments have been published. For the family Megathymidae Freeman (1951), Roever (1965) (and see Toliver, 1968) described mating and oviposition of some Southwestern U.S. Agathymus, and over a hundred years ago (1876) Riley published an excellent paper on the life history of Megathymus yuccae (Bois duval & LeConte) which included data on oviposition of the female; otherwise, only the scantiest comments have been made. C. L. Rem ington (pers. comm.) and others tell us that there is a significant pos sibility that the Hesperioidea are less closely related to the true but terflies (Papilionoidea) than to certain other Lepidoptera and even that the Megathymidae may not be phylogenetically linked to the Hesper iidae. For several years we have been making on-the-scene studies of these two aspects of megathymid behavior, both for their interest in understanding the whole ecology of these insects and for their possible reflection on higher relationships. -

Butterflies and Moths of Comal County, Texas, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail -

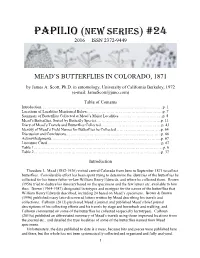

Papilio (New Series) #24 2016 Issn 2372-9449

PAPILIO (NEW SERIES) #24 2016 ISSN 2372-9449 MEAD’S BUTTERFLIES IN COLORADO, 1871 by James A. Scott, Ph.D. in entomology, University of California Berkeley, 1972 (e-mail: [email protected]) Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………..……….……………….p. 1 Locations of Localities Mentioned Below…………………………………..……..……….p. 7 Summary of Butterflies Collected at Mead’s Major Localities………………….…..……..p. 8 Mead’s Butterflies, Sorted by Butterfly Species…………………………………………..p. 11 Diary of Mead’s Travels and Butterflies Collected……………………………….……….p. 43 Identity of Mead’s Field Names for Butterflies he Collected……………………….…….p. 64 Discussion and Conclusions………………………………………………….……………p. 66 Acknowledgments………………………………………………………….……………...p. 67 Literature Cited……………………………………………………………….………...….p. 67 Table 1………………………………………………………………………….………..….p. 6 Table 2……………………………………………………………………………………..p. 37 Introduction Theodore L. Mead (1852-1936) visited central Colorado from June to September 1871 to collect butterflies. Considerable effort has been spent trying to determine the identities of the butterflies he collected for his future father-in-law William Henry Edwards, and where he collected them. Brown (1956) tried to deduce his itinerary based on the specimens and the few letters etc. available to him then. Brown (1964-1987) designated lectotypes and neotypes for the names of the butterflies that William Henry Edwards described, including 24 based on Mead’s specimens. Brown & Brown (1996) published many later-discovered letters written by Mead describing his travels and collections. Calhoun (2013) purchased Mead’s journal and published Mead’s brief journal descriptions of his collecting efforts and his travels by stage and horseback and walking, and Calhoun commented on some of the butterflies he collected (especially lectotypes). Calhoun (2015a) published an abbreviated summary of Mead’s travels using those improved locations from the journal etc., and detailed the type localities of some of the butterflies named from Mead specimens. -

Family LYCAENIDAE: 268 Species GOSSAMERWINGS

Family LYCAENIDAE: 268 species GOSSAMERWINGS Subfamily Miletinae: 1 (hypothetical) species Harvesters Feniseca tarquinius tarquinius Harvester Hypothetical, should occur in N Tamaulipas, but currently unknown from Mexico Subfamily Lycaeninae: 6 species Coppers Iophanus pyrrhias Guatemalan Copper Lycaena arota arota Tailed Copper Lycaena xanthoides xanthoides Great Copper Lycaena gorgon gorgon Gorgon Copper Lycaena helloides Purplish Copper Lycaena hermes Hermes Copper Subfamily Theclinae: 236 species Hairstreaks Tribe Theclini: 3 species Hairstreaks Hypaurotis crysalus crysalus Colorado Hairstreak Habrodais grunus grunus Golden Hairstreak verification required for Baja California Norte Habrodais poodiae Baja Hairstreak Tribe Eumaeini: 233 Hairstreaks Eumaeus childrenae Great Cycadian (= debora) Eumaeus toxea Mexican Cycadian Theorema eumenia Pale-tipped Cycadian Paiwarria antinous Felders' Hairstreak Paiwarria umbratus Thick-tailed Hairstreak Mithras sp. undescribed Pale-patched Hairstreak nr. orobia Brangas neora Common Brangas Brangas coccineifrons Black-veined Brangas Brangas carthaea Green-spotted Brangas Brangas getus Bright Brangas Thaeides theia Brown-barred Hairstreak Enos thara Thara Hairstreak Enos falerina Falerina Hairstreak Evenus regalis Regal Hairstreak Evenus coronata Crowned Hairstreak Evenus batesii Bates’ Hairstreak Atlides halesus corcorani Great Blue Hairstreak Atlides gaumeri White-tipped Hairstreak Atlides polybe Black-veined Hairstreak Atlides inachus Spying Hairstreak Atlides carpasia Jeweled Hairstreak Atlides -

Specimen Records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895

Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection 2019 Vol 3(2) Specimen records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895 Jon H. Shepard Paul C. Hammond Christopher J. Marshall Oregon State Arthropod Collection, Department of Integrative Biology, Oregon State University, Corvallis OR 97331 Cite this work, including the attached dataset, as: Shepard, J. S, P. C. Hammond, C. J. Marshall. 2019. Specimen records for North American Lepidoptera (Insecta) in the Oregon State Arthropod Collection. Lycaenidae Leach, 1815 and Riodinidae Grote, 1895. Catalog: Oregon State Arthropod Collection 3(2). (beta version). http://dx.doi.org/10.5399/osu/cat_osac.3.2.4594 Introduction These records were generated using funds from the LepNet project (Seltmann) - a national effort to create digital records for North American Lepidoptera. The dataset published herein contains the label data for all North American specimens of Lycaenidae and Riodinidae residing at the Oregon State Arthropod Collection as of March 2019. A beta version of these data records will be made available on the OSAC server (http://osac.oregonstate.edu/IPT) at the time of this publication. The beta version will be replaced in the near future with an official release (version 1.0), which will be archived as a supplemental file to this paper. Methods Basic digitization protocols and metadata standards can be found in (Shepard et al. 2018). Identifications were confirmed by Jon Shepard and Paul Hammond prior to digitization. Nomenclature follows that of (Pelham 2008). Results The holdings in these two families are extensive. Combined, they make up 25,743 specimens (24,598 Lycanidae and 1145 Riodinidae).