RIDGELAND--OAK PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT National Register Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starchitect:” Wright Finds His Voice After Being Fired

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 5, Issue 3– Pages 301-318 After the “Starchitect:” Wright Finds his Voice after Being Fired By Michael O'Brien * The term ―Starchitect‖ seems to have originated in the 1940’s to describe a ―film star who has designed a house‖ but of late has been understood as an architect who has risen to celebrity status in the general culture. Louis Sullivan, like Daniel Burnham, might have been considered a ―starchitect.‖ Starchitects are frequently associated with a unique style or approach to architecture and all who work for them, adopt this style as their own as a matter of employment. Frank Lloyd Wright was one of these architects, working under and in the idiom of Louis Sullivan for six years, learning to draw and develop motifs in the style of Louis Sullivan. Frank Lloyd Wright’s firing by Louis Sullivan in 1893 and his rapidly growing family set him on an urgent course to seek his own voice. The bootleg houses, designed outside the contract terms Wright had with Adler and Sullivan caused the separation, likely fueled by both Sullivan and Wright’s ego, which left Wright alone, separated from his ―Lieber Meister‖1 or ―Beloved Master.‖ These early houses by Wright were adaptations of various styles popular in the times, Neo-Colonial for Blossom, Victorian for Parker and Gale, each, as Wright explained were not ―radical‖ because ―I could not follow up on them.‖2 Wright, like many young architects, had not yet codified his ideas and strategies for activating space and form. How does one undertake the search for one’s language of these architectural essentials? Does one randomly pursue a course of trial and error casting about through images that capture one’s attention? Do we restrict our voice to that which has already been voiced in history? Wright’s agenda would have included the merging of space and enclosure with site and nature structured as he understood it from Sullivan’s Ornament. -

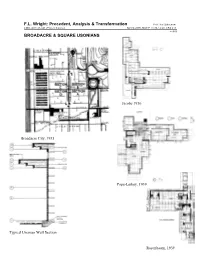

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright 1. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g04297 5. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/hhh.il0039 Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Frederick C. Robie House, 5757 Woodlawn Avenue, Lloyd Wright, architect Chicago, Cook County, IL 2. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3g01871 House ("Bogk House") for Frederick C. Bogk, 2420 North Terrace Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Stone lintel] http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?pp/hh:@field(DOCID+@lit(PA1690)) Fallingwater, State Route 381 (Stewart Township), Ohiopyle vicinity, Fayette County, PA 3. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/gsc.5a25495 Guggenheim Museum, 88th St. & 5th Ave., New York City. Under construction III. 6. 4. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c11252 http://memory.loc.gov/cgi- bin/query/r?ammem/alad:@field(DOCID+@lit(h19 Frank Lloyd Wright, Baroness Hilla Rebay, and 240)) Solomon R. Guggenheim standing beside a model of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum] / Midway Gardens, interior, Chicago, IL Margaret Carson #1 #2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 PREVIOUS NEXT RECORDS LIST NEW SEARCH HELP Item 10 of 375 How to obtain copies of this item TITLE: Some designs and executed buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright, architect CALL NUMBER: Illus in NA737.W7 A4 1917 (Case Y) [P&P] REPRODUCTION NUMBER: LC-USZC4-4297 (color film copy transparency) LC-USZ62-116098 (b&w film copy neg.) SUMMARY: Silhouette of building with steeples on cover of Japanese journal issue devoted to Frank Lloyd Wright, with Japanese and English text. MEDIUM: 1 print : woodcut(?), color. CREATED/PUBLISHED: [1917] NOTES: Illus. -

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright's Destruction of the Box And

Space of Continuity: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Destruction of the Box and Modern Conceptions of Space Late 19th-early 20th century America was an era of confluence of science, phi- losophy and religion: a contemporary polemic that equated religion (belief based on faith) with science (knowledge based on empirical data of physical phe- nomena). Modernity in 20th century America would be shaped by a pervasive theosophical atmosphere that coupled science with religion to cause a recon- sideration of mental/spiritual relationships and a redefinition of space/time concepts. Theosophy’s introduction of Eastern metaphysics to Western culture revealed possibilities of an inner self with respect to the outer being and opened the way to conceive of inner space, or interiority, and as a result interior space in buildings. To follow is a reconsideration of Wright’s work with respect to the theosophical and occult influences that guided his thinking. His contribution to today’s notion of architecture as a space of continuity will be demonstrated through case studies of his work beginning with the early Dana House (begun in 1899) to the Guggenheim Museum (completed after his death in 1959). EUGENIA VICTORIA ELLIS THE RED SQUARE Drexel University Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) began his practice in 1893 after being fired for “moonlighting” near the end of his five year contract with Adler and Sullivan, one of the then-preeminent Chicago architecture firms. Originally hired to draw the delicate ornamental details of the Auditorium Building interior, another ornamental masterpiece Wright had detailed just debuted at the World’s Columbian Exposition. -

A Retrospective on the Journey

| | EDUCATIONFRANK LLOYD ADVOCACYWRIGHT BUILDING PRESERVATION CONSERVANCY SPRING 2014 / VOLUME 5 / ISSUES 1 & 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE A Retrospective on the Journey Guest Editor: Ron Scherubel Past, Present, Future: The Conservancy at 25 2014 CONFERENCE Phoenix, Arizona | Oct. 29 – Nov. 2 Stay for a great rate in the legendary Wright- influenced Arizona Biltmore. Tour seldom-seen houses by Wright and other acclaimed architects. Get a private behind-the-scenes look at Taliesin celebrating years of saving wright West. Attend presentations and panels with world- 25 renowned Wright scholars, including a keynote speech by New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman. And cap it all off with a Gala Dinner, silent auction, Wright Spirit Awards ceremony, and much more! Register beginning in FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY June at savewright.org or call 312.663.5500 C ON T Editor’s Welcome: OK, What’s Next? 2 EN 2 Executive Editor’s Message: The Power of Community President’s Message: The Challenge Ahead 3 TS 4 Wright and Historic Preservation in the United States, 1950-1975 11 The Origins of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy 16 A Day in the Conservancy Office 20 Retrospect and Prospect 22 The ‘Saves’ in SaveWright 28 The Importance of the David and Gladys Wright House PEDRO E. GUERRERO (1917-2012) 30 Saving the David and Gladys Wright House The cover photo of this issue was taken by 38 A New Book Explores Additions to Iconic Buildings Pedro E. Guerrero, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 42 A Future for the Past trusted photographer. Guerrero was just 22 46 Up Close and Personal in 1939 when Wright took an amused look at his portfolio of school assignments and 49 Executive Director’s Letter: For the Next 25 hired him on the spot to document the con- struction at Taliesin West. -

Film and Architecture: Discovering the Self-Reflection of Frank Capra And

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2000 Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis Marie Lynore Kohler University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Kohler, Marie Lynore, "Film and architecture: Discovering the self-reflection of rF ank Capra and Frank Lloyd Wright through contextual analysis" (2000). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1120. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/c7iq-fh8b This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter fiaice, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor qualify illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

Frank Lloyd Wright and Midway Gardens'

H-Urban Baldwin on Kruty, 'Frank Lloyd Wright and Midway Gardens' Review published on Friday, January 1, 1999 Paul Kruty. Frank Lloyd Wright and Midway Gardens. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998. lii + 262 pp. $44.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-252-02366-8. Reviewed by Peter C. Baldwin (DePaul University) Published on H-Urban (January, 1999) This impressively researched and extensively illustrated volume examines one of Frank Lloyd Wright's major pieces of public architecture, a "concert garden." In this book, Paul Kruty shows that the Midway Gardens occupied a unique place in the development of Wright's style. The Midway Gardens was constructed in 1914 in Chicago's South Side, close to the University of Chicago and the site of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. An intricate arrangement of interconnected towers, multi-level dining areas, terraces and courtyards, Midway Garden was designed to be a center for musical performance and fine dining. It opened to enthusiastic local acclaim, but soon underwent some unfortunate alterations before being demolished in 1929. Kruty's book is a celebration of what he calls one of the most extraordinary monuments in the history of American architecture (p. 243). The book makes good use of a range of source material, including photographs, Wright's sketches, correspondence, and published writings, as well as articles in local newspapers and architectural journals. Kruty, an associate professor of architecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, lovingly examines the building from a variety of perspectives. His five chapters are organized by topic and can be read almost as free-standing essays. -

Frank Lloyd Wright

the drawings of MoMAExh_0703_MasterChecklist Frank Lloyd Wright ARTHUR DREXLER PUBLISHED FOR THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART BY HORIZON PRESS, NEW YORK NOTES TO THE PLATES EOs: E:')thl bit-tel Ih rxh. 703 --r~ c-,t-CM1o.HLtJO Qfdt b; hbv, 1. DORMER WINDOW, CHAUNCEY L. WILLIAMS HOUSE, RIVER fOREST, ILLINOIS. 1895. IIIE" 6. PROJECT, YAHARA BOAT CLUB, MADISON, WISCONSIN. 1902. Perspective. 8%,"x4". Pencil on tracing paper. Perspective. 6%"x22". Brown ink on tracing paper (F 9505.01) £p, , ?> ;;<41 mounted to board. Signed in red square at center right: FLIW. Collection Henry Russell Hitchcock. /P), This early study of a dormer window offers some familiar ':I:<83 signs of accomplished draftsmanship: rapid, light lines Ncrr~H, pointed with abrupt dots and dashes. 7. PROJECT, YAHARA BOAT CLUB, MADISON, WISCONSIN. 1902. Perspective (on left side of sheet including plan of second ,....,.- story). 7%"x22%". Brown ink on opaque paper mounted FZ. I 2. PROJECL LUXFER PRISM COMPANY SKYSCRAPER. 1895. to board. (F 0211.01) il.300{; NOT 6)(1t. ! Elevation and section. 281,4"x17,%".• Pencil on tracing paper. Noted at bottom right: Study lor office building E' 8. PROJECT, WALTER GERTS HOUSE, GLENCOE, ILLINOIS. 1906. facade employingMoMAExh_0703_MasterChecklist Luxf er Prisrn-lighting 189.-5. PerspectIve. 18V2"x251h", Brown ink on opaque cream- (F 9509.01) & I, :./ 'DC colored paper. (F0203.01) ltl,3:01/ In this early study for an office building facade Wright gives nearly equal stress to verticals and horizontals. The F. 19. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT STUDIO, OAK PARK, ILLINOIS. 1895. design is related to the steel framing he was later to f 1911. -

The Emil Bach House Fact Sheet

Press Contact: Lauren Russ Connect Communications 773.868.0966 [email protected] The Emil Bach House Fact Sheet About This richly conceived yet intimately scaled Emil Bach House was built by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1915 for Emil Bach, president of Chicago’s Bach Brothers Brick Co. The Emil Bach House is part of Stone Heritage Properties, the leading luxury hospitality arm of TAWANI Enterprises Address 7415 North Sheridan Road, Chicago, IL 60626 Location One block from the lake in East Rogers Park, one of Chicago’s most interesting and diverse neighborhoods Website http://www.emilbachhouse.com Opened 2014 Management TAWANI Enterprises Wayde Cartwright and Bruce Boyd Design Aesthetic The Emil Bach House looks toward future stylistic directions in Wright’s work, in its contained geometry, efficient scale, and modern window designs with white, green, and orange-yellow shapes, evoking the rhythmic triangles of Midway Gardens’ windows, none of which survive Offerings Private Vacation Rental - A study and two guest rooms on the second floor, each with a full-sized hall bathroom. The first floor includes a large gathering space with an impressive fireplace, a dining and lounge area. Beautiful outdoor spaces, include the Japanese tea House and Gardens. Rates from $495 to $1,295 per night Event Rental – The Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Emil Bach House and Japanese tea house and gardens holds up to 130 guests, including 25 guests inside. The cost is estimated at $2,595 for a five-hour minimum outside with $500 per each additional hour and $1,495 for a five-hour- minimum interior event. -

Frank Lloyd Wright Architectural Drawing

CLIENT NAME PROJECT NO. ITEM COUNT PROJECT TITLE WORK TYPE CITY STATE DATE Ablin, Dr. George Project 5812 19 drawings Dr. George Ablin house (Bakersfield, California). House Bakersfield CA 1958 Abraham Lincoln Center Project 0010 53 drawings Abraham Lincoln Center (Chicago, Illinois). Unbuilt Project Religious Chicago IL 1900 Achuff, Harold and Thomas Carroll Project 5001 21 drawings Harold Achuff and Thomas Carroll houses (Wauwatosa, Wisconsin). Unbuilt Projects Houses Wauwatosa WI 1949 Ackerman, Lee, and Associates Project 5221 7 drawings Paradise on Wheels Trailer Park for Lee Ackerman and Associates (Paradise Valley, Arizona). Trailer Park (Paradise on Wheels) Phoenix AZ 1952 Unbuilt Project Adams, Harry Project 1105 45 drawings Harry Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Oak Park IL 1912 Adams, Harry Project 1301 no drawings Harry Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Oak Park IL 1913 Adams, Lee Project 5701 11 drawings Lee Adams house (Saint Paul, Minnesota). Unbuilt Project House St. Paul MN 1956 Adams, M.H. Project 0524 1 drawing M. H. Adams house (Highland Park, Illinois). Alterations, Unbuilt Project House, alterations Highland Park IL 1905 Adams, Mary M.W. Project 0501 12 drawings Mary M. W. Adams house (Highland Park, Illinois). House Highland Park IL 1905 Adams, William and Jesse Project 0001 no drawings William and Jesse Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Chicago IL 1900 Adams, William and Jesse Project 0011 4 drawings William and Jesse Adams house (Oak Park, Illinois). House Longwood IL 1900 Adelman, Albert Project 4801 47 drawings Albert Adelman house (Fox Point, Wisconsin). Scheme 1, Unbuilt Project House (Scheme 1) Fox Point WI 1946 Adelman, Albert Project 4834 31 drawings Albert Adelman house (Fox Point, Wisconsin). -

Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview Brock Stafford Olivet Nazarene University, [email protected]

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet M.A. in Philosophy of History Theses History 8-2012 Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview Brock Stafford Olivet Nazarene University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/hist_maph Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Esthetics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Interior Architecture Commons, Philosophy of Science Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Stafford, Brock, "Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview" (2012). M.A. in Philosophy of History Theses. 6. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/hist_maph/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in M.A. in Philosophy of History Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frank Lloyd Wright: Influences and Worldview A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History and Political Science School of Graduate and Continuing Studies Olivet Nazarene University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Philosophy of History by Brock Stafford August 2012 1 © 2012 Brock Stafford ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 2 ^miature vase for the Masters in Philosophy of History? Thesis of Brock Stafford APPROVED BY William Dean. Department Chair Date David Van Heerost Thesis Adviser Date Curt Rice. Thesis Adviser Date Introduction Philosophy is to the mind of the architect as eyesight to his steps. The term “genius” when applied to him simply means a man who understands what others only know about. -

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT Biography

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT ARCHITECT February 20 - May 10, 1994 For Immediate Release FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT A Biography Frank Lloyd Wright's enduring involvement with landscape was formed in the rolling hills of southern Wisconsin, where he was born in 1867. Wright's mother encouraged his creative skills at an early age by introducing him to the "kindergarten gifts," or special toy blocks, designed by German educator Friedrich Froebel. She raised her son in an extended Welsh immigrant family steeped in a tradition of nineteenth-century romantic idealism and liberalism. In his late teens, Wright studied draftsmanship in the Engineering School of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. In 1888, he was hired as an apprentice architect by the successful Chicago firm of Adler and Sullivan, where he stayed until 1893. Despite his lack of formal training as an architect, Wright's talent was quickly appreciated. He soon became Sullivan's assistant, and Sullivan his mentor. Ultimately Wright was given his own design assignments, including the James Charnley House, Chicago (1891-92). In 1889, Wright married Catherine Lee Tobin, with whom he had six children, and built a Shingle Style house in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park. Four years later, he established his own practice. During the 1890s, while Wright was working on domestic commissions, his search for an American architecture resulted in the horizontal composition, simplified planar forms, and open plans that culminated in the Prairie House in 1900. - more - epartment of Public Information The Museum of Modern Art 1 1 West 53 Street New York, NY 10019 212.708.9750 2 The first decade of the twentieth century saw the maturing of Wright's architectural abilities and the expansion of his professional practice.