Vanuatu: Disaster Risk Profile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019-2020 Annual Report

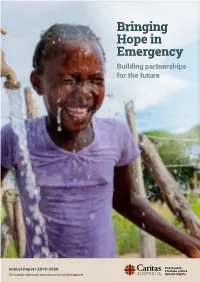

Bringing Hope in Emergency Building partnerships for the future Annual Report 2019-2020 The Catholica BRINGING Agency HOPE for IN EMERGENCYInternational Aid and Development “The Spirit of the Lord is Contents upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good Our Vision news to the poor. He has Vision and Mission 1 sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery From the Chair 2 of sight to the blind, to let From the CEO 3 the oppressed go free, to Principles 4 proclaim the year of the Strategy 5 Lord’s favour.” Our Work Luke 4:17-19 Where we work 6-7 Myanmar 8 Australia 9 Lebanon 10 South Sudan 11 Solomon Islands 12 Vietnam 13 Evaluation and learning 14 COVID-19 response 15 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be aware that this publication may contain images or names of people who have since passed away. Caritas Our Year Australia acknowledges the traditional owners and custodians, past and present, of the land on which all our offices are located. Year in review 16-17 Our year in advocacy 18 Cover: Villagers in Afghanistan learn how to protect themselves from COVID-19 In their own words 19 through hand-washing and hygiene measures. Photo: Stefanie Glinski/Catholic Relief Services Financial snapshot 20-21 Inside cover: A child in the Turkana region of Kenya, an arid region and the poorest in Kenya, with 60% of the population living in extreme poverty. Photo: Garry Walsh, Trocaire Fundraising spotlight 22 Design: Three Blocks Left ABN 90 970 605 069 Published November 2020 by Caritas Australia © Copyright Caritas Australia 2020 Leadership ISSN 2201-3083 In keeping with Caritas Australia’s high standard of transparency, this version has Our Diocesan network 23 been updated to correct minor typographical errors from an earlier version. -

Accept Corona As Part of Life, Return to Normalcy

Indian Horizon National English Daily [email protected] www.indianhorizon.org RNI NO: DELENG/2013/51507 In memory of Dr Asima Kemal and Prof. Dr. Salim W Kemal [email protected] Volume Issue No: 139 Published from New Delhi & Hyderabad New Delhi, Thursday, May 21, 2020 No: 7 Pages 12 + 4 pull out (P16) Price: 3.00 INS TO SC: CENTRE, STATES TOOK HCQ AFTER VALET MAIN AIM IS TO WIN AN OLY OWE SEVERAL CRORES’ DUES TESTED COVID POSITIVE, MEDAL OF DIFFERENT COLOUR TO MEDIA INDUSTRY SAYS TRUMP IN TOKYO: MARY P-3 P-8 P-11 HOLIDAY NOTICE New Delhi, May 20 (IANS) mentation of the scheme that Prime Minister Narendra Modi NARENDRA MODI : is expected to bring about Blue THE WORLD UNDER ATTACK on Wednesday said several de- Revolution through sustainable cisions taken by the Cabinet Migrants, fishermen, and responsible development SCOURGE OF CORONAVIRUS today focused on welfare of of fisheries sector in India un- migrants, poor and senior citi- senior citizen to gain from der two components -- Central zens, adding these would facili- Sector Scheme and Centrally TOTAL TALLY IN INDIA Our office will be tate easier availability of credit Cabinet decisions Sponsored Scheme -- at a to- mounts to 1,06,750, death closed on 21st of May, and create opportunities in the tal estimated investment of Rs 2020 on the occasion fisheries sector. equate livelihood for rural-ur- 20,050 crore. toll 3,303 of Shab-E-Qadr. While welcoming the Cabi- ban communities.On ‘Pradhan The scheme is likely to ad- Therefore, net’s decision on formalisation Mantri Matsya Sampada Yo- dress the critical gaps in the of microfood processing enter- jana’, Modi said it will “revolu- fisheries sector and realize its there will be no issue prises, PM Modi tweeted: “The tionise the fisheries sector”. -

Being Prepared for Unprecedented Times Peter Layton

Being prepared for unprecedented times National mobilisation conceptualisations and their implications Peter Layton 1 2 3 BEING PREPARED FOR UNPRECEDENTED TIMES National mobilisation conceptualisations and their implications Peter Layton 3 About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. Visit us at: www.griffith.edu.au/asiainstitute About the publication This paper has been developed with the support of the Directorate of Mobilisation, Force Design Division within the Australian Department of Defence. Mobilisation involves civil society, emergency services and all levels of government. The sharing of the research undertaken aims to encourage informed community debate. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Australian Government or the Department of Defence, or any part thereof. -

2021 07 21 USAID-BHA Success Story

Photo by Arlene Bax/CARE Building Back Better in Vanuatu Vanuatu is one of the world’s most hazard- prone countries, highly susceptible to earthquakes, volcanic activity, tropical cyclones, and climate change impacts such as rising sea levels. In April 2020, Tropical Cyclone Harold made landfall over northern Vanuatu, affecting more than 130,000 people, representing more than 40 who conducted trainings on how to use percent of the country’s population. locally available coconut palm leaves as an Affected populations on Pentecost Island alternate roofing material. faced myriad challenges in Harold’s aftermath; among the most difficult was With support from USAID/BHA and other rebuilding shelters. As in the wake of many donors, CARE provided construction sudden-onset disasters, availability of materials and tools to more than 1,000 building materials and labor were limited. households and trained 40 community Additionally, restrictions to slow the spread members as chainsaw operators to process of coronavirus disease (COVID-19), such as fallen trees into timber, further expanding border closures, hindered relief actors’ local shelter material options. CARE also capacity to provide materials and staff to trained nearly 120 community members as augment local response efforts. shelter focal points, supporting efforts to rebuild using international guidelines for With support from USAID’s Bureau for resilient, safe shelter construction. These Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA), shelter focal points—of whom more than CARE Vanuatu assisted residents of 40 percent are women—are now supporting Pentecost to rebuild shelters by employing communities to rebuild after the cyclone. local knowledge and construction materials. “Before, we thought only men could do this Immediately after the cyclone, community work and make decisions, but today, things members gathered natangura palm leaves to have changed,” explains Peter Watas, a local reconstruct damaged roofs. -

Central Banks As Economic Institutions: a Roundtable Debate

Central Banks as Economic Institutions Roundtable Debate∗ ∗∗ Willem H. Buiter Professor of European Political Economy European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science, Universiteit van Amsterdam, NBER and CEPR ∗ These notes are based on my contribution to the Roundtable Central Banks as Economic Institutions, held in Paris at the headquarters of the Saint-Gobain Group, on November 30 and December 1, 2006, at the Conference Central Banks as Economic Institutions, organised by the Cournot Centre for Economic Studies. I would like to thank the Centre Cournot and the organiser for their invitation and their hospitality. ∗∗ © Willem H. Buiter, 2007 Introduction As my starting contribution to this Roundtable debate, I shall address three issues: 1. Some implications of globalisation for central banking. 2. The objectives of the central bank. 3. Operational independence and accountability and the case for the minimalist central bank.1 1. Globalisation and central banking In a world with floating exchange rates, international coordination between national central banks (NCBs) for normal (non- crisis) monetary policy purposes is, for all practical purposes, redundant. Co-ordination between NCBs could make sense if monetary policy were an effective instrument for fine-tuning the business cycle. However, the lingering belief in the effectiveness of monetary policy as a cyclical stabilisation instrument is, in my view, evidence of the ‘fine tuning illusion’ or ‘fine tuning fallacy’ at work. In a world with unrestricted international -

4. the TROPICS—HJ Diamond and CJ Schreck, Eds

4. THE TROPICS—H. J. Diamond and C. J. Schreck, Eds. Pacific, South Indian, and Australian basins were a. Overview—H. J. Diamond and C. J. Schreck all particularly quiet, each having about half their The Tropics in 2017 were dominated by neutral median ACE. El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) condi- Three tropical cyclones (TCs) reached the Saffir– tions during most of the year, with the onset of Simpson scale category 5 intensity level—two in the La Niña conditions occurring during boreal autumn. North Atlantic and one in the western North Pacific Although the year began ENSO-neutral, it initially basins. This number was less than half of the eight featured cooler-than-average sea surface tempera- category 5 storms recorded in 2015 (Diamond and tures (SSTs) in the central and east-central equatorial Schreck 2016), and was one fewer than the four re- Pacific, along with lingering La Niña impacts in the corded in 2016 (Diamond and Schreck 2017). atmospheric circulation. These conditions followed The editors of this chapter would like to insert two the abrupt end of a weak and short-lived La Niña personal notes recognizing the passing of two giants during 2016, which lasted from the July–September in the field of tropical meteorology. season until late December. Charles J. Neumann passed away on 14 November Equatorial Pacific SST anomalies warmed con- 2017, at the age of 92. Upon graduation from MIT siderably during the first several months of 2017 in 1946, Charlie volunteered as a weather officer in and by late boreal spring and early summer, the the Navy’s first airborne typhoon reconnaissance anomalies were just shy of reaching El Niño thresh- unit in the Pacific. -

Pacific Study (Focusing on Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu

1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Hazard exposure 1.1. Pacific island countries (PICs) are vulnerable to a broad range of natural disasters stemming from hydro-meteorological (such as cyclones, droughts, landslide and floods) and geo-physical hazards (volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and tsunamis). In any given year, it is likely that Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu are either hit by, or recovering from, a major natural disaster. 1.2. The impact of natural disasters is estimated by the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative as equivalent to an annualized loss of 6.6% of GDP in Vanuatu, and 4.3% in Tonga. For Fiji, the average asset losses due to tropical cyclones and floods are estimated at more than 5%. 1.3. In 2014, Tropical Cyclone (TC) Ian caused damage equivalent to 11% to Tonga's GDP. It was followed in 2018 by damage close to 38% of GDP from TC Gita. In 2015, category five TC Pam displaced 25% of Vanuatu's population and provoked damage estimated at 64% of GDP. In Fiji, Tropical Cyclone Winston affected 62% of the population and wrought damage amounting to 31% of GDP, only some three and a half years after the passage of Tropical Cyclone Evan. 1.4. Vanuatu and Tonga rank number one and two in global indices of natural disaster risk. Seismic hazard is an ever-present danger for both, together with secondary risks arising from tsunamis and landslides. Some 240 earthquakes, ranging in magnitude between 3.3 and 7.1 on the Richter Scale, struck Vanuatu and its surrounding region in the first ten months of 2018. -

ETC Vanuatu Sitrep #4.Pdf

Vanuatu - Cyclone Pam ETC Situation Report #04 Reporting period 24/03/2015 to 07/04/2015 Highlights • 1x emergency.lu VSAT was successfully installed on Tanna Island. • A BT team of 4x specialists successfully installed 1x VSAT on Ambae Island and 1x VSAT on Malekula Island. • The ETC is now providing shared internet connectivity services at 7x sites across Vanuatu. 2x sites have been decommissioned. • The ETC continues to support the government with its communications needs to enable it to communicate with people on remote islands. • Logistics is a major challenge as shipping equipment from Port Vila to the islands is costly and takes up valuable time. Situation Overview Now in the fourth week of the operation after Tropical Cyclone Pam hit Vanuatu, the Emergency Telecommunications Cluster (ETC) is working closely with the Government of Vanuatu to coordinate ICT efforts to ensure a swift and efficient response, avoid duplication of efforts and ensure resources are channeled where they are most needed. The National Disaster Management Office (NDMO) has indicated that it expects the national network backbone to be operational within three weeks and further deployment of ETC equipment is no longer necessary. Basic GSM services have been largely restored and local Internet Service Providers are working hard to reestablish the national network backbone. 3G is still a challenge. Response 1x emergency.lu VSAT was successfully installed in Isangel (Tanna Island), replacing the immediate response portable satellite terminal (BGAN), provided by Telecoms Sans Frontieres (TSF), in order to provide extended internet connectivity services to the humanitarian community. Page 1 of 5 The ETC provides timely, predictable and effective Information Communications Technology services to support the humanitarian community in carrying-out their work efficiently, effectively and safely. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments Through 2016

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 constituteproject.org Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments through 2016 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 Table of contents CHAPTER I: THE STATE AND THE CONSTITUTION . 7 1. The State . 7 2. Constitution is supreme law . 7 CHAPTER II: PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS OF THE INDIVIDUAL . 7 3. Fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual . 7 4. Protection of right to life . 7 5. Protection of right to personal liberty . 8 6. Protection from slavery and forced labour . 10 7. Protection from inhuman treatment . 11 8. Protection from deprivation of property . 11 9. Protection for privacy of home and other property . 14 10. Provisions to secure protection of law . 15 11. Protection of freedom of conscience . 17 12. Protection of freedom of expression . 17 13. Protection of freedom of assembly and association . 18 14. Protection of freedom to establish schools . 18 15. Protection of freedom of movement . 19 16. Protection from discrimination . 20 17. Enforcement of protective provisions . 21 17A. Payment or retiring allowances to Members . 22 18. Derogations from fundamental rights and freedoms under emergency powers . 22 19. Interpretation and savings . 23 CHAPTER III: CITIZENSHIP . 25 20. Persons who became citizens on 12 March 1968 . 25 21. Persons entitled to be registered as citizens . 25 22. Persons born in Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . 26 23. Persons born outside Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . -

Shefa Province Skills Plan 2015 - 2018

SHEFA PROVINCE SKILLS PLAN 2015 - 2018 Skills for Economic Growth CONTENTS Abbreviations 2 Forward by the Shefa Secretary General 3 1 Introduction 4 2 Vanuatu Training Landscape 6 3 Purpose 8 4 Shefa Province 9 5 Agriculture and Horticulture Sectors 12 6 Forestry Sector 18 7 Livestock Sector 21 8 Fisheries and Aquaculture Sector 25 9 Tourism and Hospitality Sector 28 10 Construction and Property Services Sector 32 11 Transport and Logistics Sector 37 12 Cross Sector 40 Appendix 1: Employability and Generic Skills 46 Appendix 2: Acknowledgments 49 ABBREVIATIONS BDS Business Development Services FAD Fish Aggregating Device FMA Fisheries Management Act GESI Gender Equity and Social Inclusion MoALFFBS Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Forestry, Fisheries and Bio-Security MoET Ministry of Education and Training NGO Non-Government Organisations PSET Post School Education and Training PTB Provincial Training Boards TVET Technical and Vocational Education and Training VAC Vanuatu Agriculture College VCCI Vanuatu Chamber of Commerce and Industry VESSP Vanuatu Education Sector Strategic Plan VIT Vanuatu Institute of Technology VQA Vanuatu Qualifi cations Authority FORWARD BY THE SHEFA SECRETARY GENERAL - MR MICHEL KALWORAI It is with much pleasure that I present to you our fi rst Skills Plan for Shefa Province; it specifi cally captures our training and learning development projections for four years, commencing this year 2015 and concluding in 2018. It also draws from, and refl ects, the Shefa Province Corporate Plan. It will be skill development that will assist us in improving and developing new infrastructure that will benefi t all in the province. It will drive the efforts of industry sectors seeking to achieve their commercial potential, in particular our agriculture and tourism sectors, both of which are seeking to improve productivity by having a skilled and qualifi ed workforce. -

A Year in Review 2016-2017 Women Leading Through Philanthropy CONTENTS It’S What’S on the Inside That Counts a Year in Review 2016-2017

a year in review 2016-2017 women leading through philanthropy CONTENTS it’s what’s on the inside that counts a year in review 2016-2017 Thank you from Society of Women Leaders CONTENTS Interim Co-Chairs Anita Pahor and Susan Wynne 4 it’s what’s on the A message of support from Australian Red Cross CEO Judy Slatyer 6 inside that counts Our vision 7 Transforming lives: the impact of our philanthropy 8 Young Parents Program 9 International Aid Workers 11 Migration Support Programs 14 Empowering communities in Indonesia 16 A daily phone call for people living alone 18 A year of action: philanthropy, education and friendship 20 Our members, very special gentlemen and supporters 23 Strategy, planning and leadership 24 About Red Cross 26 Inside cover image: Australian Red Cross deployed Aid Worker Jess Lees as part of a Field Assessment and Coordination Team to Somaliland. 3 Anita Pahor & Susan Wynne Co-Chairs Society of Women Leaders thank It has been our privilege to lead this remarkable circle of giving during the YOU past few months, together with Interim Partnership Advisers Rowena McGilvray and Kate O’Callaghan. One of the privileges and responsibilities of being a member of this circle of giving is becoming more educated about humanitarian issues that face our communities. We gain access to the world’s best minds and most active agents of humanitarian diplomacy. Australian Red Cross CEO Judy Slatyer and her senior staff personally share their vision for the organisation with us and discuss their plans to mobilise even more people in the Australian community to commit to humanitarian values.