Hans Von Aachen's Paintings on Stone

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans Rottenhammer's Use of Networks in the Copper

arts Article Intermediaries and the Market: Hans Rottenhammer’s Use of Networks in the Copper Painting Market Sophia Quach McCabe Department of History of Art and Architecture, University of California, Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA 93106, USA; [email protected] Received: 1 February 2019; Accepted: 16 June 2019; Published: 24 June 2019 Abstract: In Willem van Haecht’s Gallery of Cornelis van der Geest, The Last Judgment by the German artist Hans Rottenhammer stands prominently in the foreground. Signed and dated 1598, it is one of many copper panel paintings Rottenhammer produced and sent north of the Alps during his decade-long sojourn in Venice. That the work was valued alongside those of Renaissance masters raises questions about Rottenhammer’s artistic status and how the painting reached Antwerp. This essay examines Rottenhammer’s international market as a function of his relationships with artist-friends and agents, especially those in Venice’s German merchant community. By employing digital visualization tools alongside the study of archival documents, the essay attends to the intermediary connections within a social network, and their effects on the art market. It argues for Rottenhammer’s use of—and negotiation with—intermediaries to establish an international career. Through digital platforms, such as ArcGIS and Palladio, the artist’s patronage group is shown to have shifted geographically, from multiple countries around 1600 to Germany and Antwerp after 1606, when he relocated to Augsburg. Yet, the same trusted friends and associates he had established in Italy continued to participate in Rottenhammer’s business of art. Keywords: Hans Rottenhammer; social network; intermediaries; mediation; digital humanities; digital art history; merchants; art market; copper painting; Jan Brueghel the Elder 1. -

The Craftsman Revealed: Adriaen De Vries, Sculptor

This page intentionally left blank The Craftsman Revealed Adriaen de Vries Sculptor in Bronze This page intentionally left blank The Craftsman Revealed Adriaen de Vries Sculptor in Bronze Jane Bassett with contributions by Peggy Fogelman, David A. Scott, and Ronald C. Schmidtling II THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Los ANGELES The Getty Conservation Institute Timothy P. Whalen, Director Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, Programs The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance conservation practice in the visual arts—broadly interpreted to include objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through scientific research, education and training, model field projects, and the dissemination of the results of both its own work and the work of others in the field. In all its endeavors, the GCI focuses on the creation and delivery of knowledge that will benefit the professionals and organizations responsible for the conservation of the world's cultural heritage. Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 90049-1682 www.getty.edu © 2008 J. Paul Getty Trust Gregory M. Britton, Publisher Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Tevvy Ball, Editor Sheila Berg, Copy Editor Pamela Heath, Production Coordinator Hespenheide Design, Designer Printed and bound in China through Asia Pacific Offset, Inc. FRONT COVER: Radiograph of Juggling Man, by Adriaen de Vries. Bronze. Cast in Prague, 1610–1615. J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Inv. no. 90.SB.44. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bassett, Jane. The craftsman revealed : Adriaen de Vries, sculptor in bronze / Jane Bassett ; with contributions by Peggy Fogelman, David A. Scott, and Ronald C. -

Christoph Gertner ADORATION of the SHEPHERDS

Christoph Gertner Arnstadt, Thuringia circa 1580-1620 ADORATION OF THE SHEPHERDS Christoph Gertner Arnstadt, Thuringia, circa 1580-1620 Adoration of the Shepherds Oil on black slate and agate 26.4 x 13.9 cm The present painting of the Adoration of the Shepherds, oil on black stone (slate or basalt?) and agate (according to the owner and conservator), 26,4 X 13.9 cm, can be unequivocally attributed to Christoph Gertner, even on the basis of photographs. It represents the same subject (shepherds, Mary, and Joseph adoring the Christ Child) has almost identical dimensions (26.4 x 13.9 cm versus 26.5 x 14 cm) to a painting that has been attributed to Christoph Gertner, now in a private collection in New York.1 It is also similarly constructed. In both instances a circular piece of lighter colored stone, in the New York example alabaster, has been inserted into an opening and conjoined to darker colored stone, in New York, black marble. With the exception of the head of the Virgin, the poses and gestures of the figures in both instances are identical. The touch (with impasto highlights on the edges of the folds, and the black of the stone used for shadows, for example). The painting under consideration is however not a copy of the New York version, but a another version of the invention. The composition has been altered to concentrate on the Shepherds and Holy Family at the bottom; the shepherd on the left has been pushed to the edge of the composition, and the amount of the scene in heaven has been diminished slightly. -

Thomas Dacosta Kaufmann 146 Mercer Street Princeton, N.J

Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann 146 Mercer Street Princeton, N.J. 08540 Tel: 609-921-0154 ; cell : 609-865-8645 Fax: 609-258-0103 email: [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE Education Collegiate School, New York, valedictorian Yale University, B.A., summa cum laude with exceptional distinction in History, the Arts and Letters, 1970 Yale University, M.A., with Honors, in History, 1970 Warburg Institute, University of London, M.Phil. Dissertation: Theories of Light in Renaissance Art and Science (Advisor: E. H. Gombrich), 1972 Harvard University, Ph. D., in Fine Arts Dissertation: “Variations on the Imperial Theme; Studies in Ceremonial Art, and Collecting in the Age of Maximilian II and Rudolf II” (Advisor: J. S. Ackerman), 1977 Employment Princeton University, Department of Art and Archaeology Frederick Marquand Professor of Art and Archaeology, 2007- Assistant Professor, 1977-1983; Associate Professor, 1983-1989; Professor, 1989-; Junior Advisor, 1978-1980; Departmental Representative (i.e., vice-chair for Undergraduate Studies, and Senior Advisor), 1983-1987, 1990-1991 Chairman, Committee for Renaissance Studies, 1990-93 University of San Marino, History Department, Professor, Lecture Cycle, 2010 Summer Art Theory Seminar, Globalization, School of Art Institute of Chicago, 2008, Professor Forschungsschwerpunkt Geschichte und Kultur Ostmitteleuropa (former Academy of Sciences, Berlin; Max-Planck-Gesellschaft), Visiting Professor, 1994 Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum, Braunschweig, Stiftung Niedersachsen, Summer Course, Visiting Professor, 1994 University of Pennsylvania, Department of Art History Visiting Professor, 1980 Awards, Fellowships, and other Distinctions Elected Member, Latvian Academy of Sciences, 2020 Honorary Doctorate (Doctor historiae artrium, h.c.), Masaryk University, Brno, 2013 Wissenschaftlicher Gast, Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz, 2013 Nina Maria Gorissen Fellow in History (Berlin Prize Fellowship), American Academy in Berlin, 2013 Honorary Doctorate (Doctor phil. -

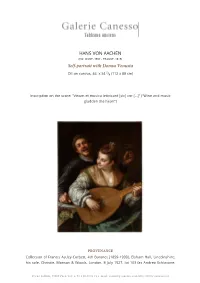

Self-Portrait with Donna Venusta Is One of the Best-Documented and Most Admired Compositions by This German Painter, Whose Life Was Defined by Extensive Travel

HANS VON AACHEN (COLOGNE, 1552 - PRAGUE, 1615) Oil on canvas, 44 x 34 ⁵/₈ (112 x 88 cm) Inscription on the score: “Vinum et musica letivicant [sic] cor […]” (“Wine and music gladden the heart”) Collection of Francis Astley-Corbett, 4th Baronet [1859-1939], Elsham Hall, Lincolnshire; his sale, Christie, Manson & Woods, London, 8 July 1927, lot 103 (as Andrea Schiavone; 26 rue Laffitte, 75009 Paris Tel : + 33 1 40 22 61 71 e-mail : [email protected] http://www.canesso.art 44 x 34½ in (111.8 x 87.6 cm), sold for £78.15.0 [75 guineas] to the dealer Frank Sabin; Paris, private collection; Venice, with Ettore Viancini; 1975, private collection. SELECTED LITERATURE -Joachim Jacoby, Hans von Aachen 1552-1615, Berlin, 2000, pp. 16-17, fig. I, pp. 203-205, no. 61 (with earlier literature); -Bernard Aikema, in Hans von Aachen 1552-1615. Court artist in Europe, exh. cat. ed. by Thomas Fusenig (Aachen, Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, 11 March – 1 June 2010; Prague, Císařská konírna, 1 July – 3 October 2010; Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum, 19 October 2010 – 9 January 2011), pp. 85, 89, 96, and pp. 104-105, no. 6; -Bernard Aikema, “Hans von Aachen in Italy: A Reappraisal”, in Hans von Aachen in context (symposium proceedings, Prague, 22-25 September 2010), ed. by Lubomír Konečný and Štěpán Vácha, Prague, 2012, pp. 20-21, fig. 3; -Lothar Sickel, “Anthonis Santvoort. Ein niederländischer Maler, Verleger und Kunstvermittler in Rom. Mit einem Exkurs zum Testament Cornelis Corts”, in Ein privilegiertes Medium und die Bildkulturen Europas. Deutsche, französische und niederländische Kupferstecher und Graphikverleger in Rom von 1590 bis 1630 (symposium proceedings, Rome, Bibliotheca Hertziana, 10-11 November 2008), ed. -

Masterpieces, Altarpieces, and Devotional Prints: Close and Distant Encounters with Michelangelo's Vatican Pietà

religions Article Masterpieces, Altarpieces, and Devotional Prints: Close and Distant Encounters with Michelangelo’s Vatican Pietà Gra˙zynaJurkowlaniec Institute of Art History, University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmie´scie26/28, 00-927 Warszawa, Poland; [email protected] Received: 2 April 2019; Accepted: 1 May 2019; Published: 7 May 2019 Abstract: Focussing on the response to the Vatican Pietà and perversely using as a point of departure a 1549 remark on Michelangelo as an ‘inventor of filth,’ this article aims to present Michelangelo as an involuntary inventor of devotional images. The article explores hitherto unconsidered aspects of the reception of the Vatican Pietà from the mid-sixteenth into the early seventeenth century. The material includes mediocre anonymous woodcuts, and elaborate engravings and etchings by renowned masters: Giulio Bonasone, Cornelis Cort, Jacques Callot and Lucas Kilian. A complex chain of relationships is traced among various works, some referring directly to the Vatican Pietà, some indirectly, neither designed nor perceived as its reproductions, but conceived as illustrations of the Syriac translation of the New Testament, of Latin and German editions of Peter Canisius’s Little catechism, of the frontispiece of the Règlement et établissement de la Compagnie des Pénitents blancs de la Ville de Nancy—but above all, widespread as single-leaf popular devotional images. Keywords: devotional image; Pietà; Michelangelo Buonarroti; reception 1. Introduction Michelangelo’s contemporaries unanimously described his Vatican Pietà (Figure1), carved between 1498 and 1500, as the work that ensured the fame of the young artist and thus paved the way for his subsequent career (Vasari 1962); (Condivi 2009). -

Dianakosslerovamlittthesis1988 Original C.Pdf

University of St Andrews Full metadata for this thesis is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by original copyright M.LITT. (ART GALLERY STUDIES) DISSERTATION AEGIDIDS SADELER'S ENGRAVINGS IN TM M OF SCOTLAND VOLUME I BY DIANA KOSSLEROVA DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF ST ANDREWS 1988 I, Diana Kosslerova, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 24 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. date.?.0. /V. ?... signature of candidate; I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. in October 1985 the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St. Andrews between October 1985 and April 1988. date... ????... signature of candidate. I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of in the University of St. Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. datefV.Q. signature of supervisor, In submitting this thesis to the University of St. Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. -

Hans Von Aachen in Context. Proceedings of the International Conference, Prague 22-25 September 2010, Prag: Artefactum 2012, in Sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr

Citation style Andrea Gáldy: Rezension von: Lubomir Konečný / Štěpán Vácha (Hgg.): Hans von Aachen in Context. Proceedings of the International Conference, Prague 22-25 September 2010, Prag: Artefactum 2012, in sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 3 [15.03.2015], URL:http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/03/23177.html First published: http://www.sehepunkte.de/2015/03/23177.html copyright This article may be downloaded and/or used within the private copying exemption. Any further use without permission of the rights owner shall be subject to legal licences (§§ 44a-63a UrhG / German Copyright Act). sehepunkte 15 (2015), Nr. 3 Lubomir Konečný / Štěpán Vácha (Hgg.): Hans von Aachen in Context The present volume publishes the proceedings of an international conference, which took place in Prague in September 2010. The chapters are composed by a very cosmopolitan cast of scholars and reflect the papers given at the close of the Prague leg of a major exhibition on Hans von Aachen as court artist which travelled from Aachen to the Czech Republic and then on to Vienna in 2010/2011. Exhibition, conference and, finally, the published volume traced the career of the artist who eventually became the main artistic impresario at the court of Rudolf II at Prague. Trained in Cologne and Italy (in particular Venice and the Veneto), Hans von Aachen worked for the Wittelsbach family in Munich before gaining a role at the imperial court that was compared to the relationship of Apelles and Alexander and may be compared to that of Vasari and the Medici. Highly popular during his life-time, Hans von Aachen was well inserted in the main networks of agents and court artists; his biography was discussed in the major art-historical literature of van Mander, Sandrart und Baldinucci. -

Title Narrative and Material: Paintings on Rare Metal, Stone and Fabric in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries Au

Narrative and Material: Paintings on Rare Metal, Stone and Title Fabric in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries Author(s) Hirakawa, Kayo Citation Aspects of Narrative in Art History (2014): 33-45 Issue Date 2014 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/227395 © 2014 Graduate School of Letters, Kyoto University; This is a Right digital offprint for restricted use only Type Conference Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 33 Narrative and Material: Paintings on Rare Metal, Stone and Fabric in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries Kayo Hirakawa 1. Introduction monumental body of Christ with anatomical details From the late sixteenth century to the early can be seen, and the brilliant colors of pink, blue, seventeenth century in Europe, various materials came yellow and green fascinate our eyes. A series of to be used as the painting-supports. Copper, tin, slate, mythological paintings Hercules and Omphale (fig. 2) marble, lapis lazuli, silk and others added a rare and and Vulcan and Maia (fig. 3) painted for Rudolf II curious appearance to artworks. In some cases, their show an intimate lovers’ atmosphere with detailed surface was left partly unpainted and was converted to depictions of small objects such as Maia’s cornucopia be part of the pictorial representation. Art lovers at that of fruits, Vulcan’s hammer and blacksmith works, time highly valued the paintings on rare materials Hercules’ club held by Omphale, and a spool and especially for their unique appearance, and ardently thread in Hercules’ hands. The Calvary (fig. 4) by Jan collected them in their collection rooms, studiolo, Brueghel the Elder, another virtuoso of the copperplate cabinet or Kunstkammer. -

An Allegory of Sight Attributed to Hans Christoph Schürer in the Nationalmuseum

An Allegory of Sight attributed to Hans Christoph Schürer in the Nationalmuseum Thomas Fusenig PhD, Essen, Germany Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum Stockholm Volume 21 Art Bulletin of Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Photo Credits Every effort has been made by the publisher to is published with generous support from © Palazzo d’Arco, Mantua, inv. 4494/Photo: credit organizations and individuals with regard the Friends of the Nationalmuseum. Nationalmuseum Image Archives, from Domenico to the supply of photographs. Please notify the Fetti 1588/89–1623, Eduard Safarik (ed.), Milan, publisher regarding corrections. Nationalmuseum collaborates with 1996, p. 280, fig. 82 (Figs. 2 and 9A, pp. 13 and Svenska Dagbladet and Grand Hôtel Stockholm. 19) Graphic Design We would also like to thank FCB Fältman & © Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow BIGG Malmén. (Fig. 3, p. 13) © bpk/Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/ Layout Cover Illustrations Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut (Figs. 4, 5B, 6B and Agneta Bervokk Domenico Fetti (1588/89–1623), David with the 7B, pp. 14–17) Head of Goliath, c. 1617/20. Oil on canvas, © Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Translation and Language Editing 161 x 99.5 cm. Purchase: The Wiros Fund. Content Program (Figs. 8 and 10B, pp. 18 and Gabriella Berggren, Martin Naylor and Kristin Nationalmuseum, NM 7280. 20) Belkin. © CATS-SMK (Fig. 10A, p. 20) Publisher © Dag Fosse/KODE (p. 25) Publishing Berndt Arell, Director General © Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design/ Ingrid Lindell (Publications Manager) and The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Janna Herder (Editor). Editor Design, Oslo (p. 28) Janna Herder © SMK Photo (p. -

Download Download

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol. 9, No. 2, June 2020 DOI: 10.7596/taksad.v9i2.2570 Citation: Romanenkova, J., Bratus, I., Kuzmenko, H., & Streltsova, S. (2020). Art during the Reign of Rudolf II as Quintessence of Leading Mannerism Trend at Prague Art Center. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 9(2), 395-407. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v9i2.2570 Art during the Reign of Rudolf II as Quintessence of Leading Mannerism Trend at Prague Art Center Julia Romanenkova 1, Ivan Bratus 2, Halyna Kuzmenko 3, Svitlana Streltsova 4 Abstract This article is devoted to Rudolfine art as one of the style-forming components and a significant trend in European Mannerism of the 16-17th centuries. A general overview of this style, necessary preconditions that led to its emergence in the artistic culture of Europe, Mannerism major trends and its vectors of spreading in Europe, the role of Rudolfine artists in this process, are laid out in this work. We emphasized the lack of adequate research made in the field of Art History. The personal influence of Emperor Rudolf II on the formation of court art at that time was pointed out. We looked into the background and circumstances at which the Prague Art Center was established by the Emperor and how he provided patronage to the arts and science. The importance of works by prominent artists of the Rudolfine era who worked at the Prague Art Center is highlighted. The main directions of Mannerism distribution through European countries, mainly its further adaptation and style transformation depending on the geographical location, grounds on why the art was so influenced by the Italian movement, the approach and tools of Mannerism in one of the leading European courts. -

April 2010 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 27, No. 1 www.hnanews.org April 2010 Hans von Aachen, The Fall of Phaeton, c. 1600. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, on loan to Schloss Ambras In the exhibition Hans von Aachen (1552-1615), Hofkünstler in Europa, Suermondt-Ludwig Museum, Aachen, March 11 – June 13, 2010; Prague Castle Gallery, July 1 – October 3, 2010; Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, October 19, 2010 – January 9, 2011. © KHM HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Dagmar Eichberger Contents Wayne Franits Matt Kavaler HNA News ............................................................................1 Henry Luttikhuizen Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Shelley Perlove Exhibitions ............................................................................ 3 Joaneath