Images of God in Japanese New Religions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Perkins School of Theology

FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF Bridwell Library PERKINS SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 http://www.archive.org/details/historyofperkinsOOgrim A History of the Perkins School of Theology A History of the PERKINS SCHOOL of Theology Lewis Howard Grimes Edited by Roger Loyd Southern Methodist University Press Dallas — Copyright © 1993 by Southern Methodist University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America FIRST EDITION, 1 993 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions Southern Methodist University Press Box 415 Dallas, Texas 75275 Unless otherwise credited, photographs are from the archives of the Perkins School of Theology. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grimes, Lewis Howard, 1915-1989. A history of the Perkins School of Theology / Lewis Howard Grimes, — ist ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-87074-346-5 I. Perkins School of Theology—History. 2. Theological seminaries, Methodist—Texas— Dallas— History. 3. Dallas (Tex.) Church history. I. Loyd, Roger. II. Title. BV4070.P47G75 1993 2 207'. 76428 1 —dc20 92-39891 . 1 Contents Preface Roger Loyd ix Introduction William Richey Hogg xi 1 The Birth of a University 1 2. TheEarly Years: 1910-20 13 3. ANewDean, a New Building: 1920-26 27 4. Controversy and Conflict 39 5. The Kilgore Years: 1926-33 51 6. The Hawk Years: 1933-5 63 7. Building the New Quadrangle: 1944-51 81 8. The Cuninggim Years: 1951-60 91 9. The Quadrangle Comes to Life 105 10. The Quillian Years: 1960-69 125 11. -

The Japanese New Religion Oomoto

UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL THE JAPANESE NEW RELIGION OOMOTO: RECONCILIATION OF NATNIST AND INTERNATIONALIST TRENDS THE SIS SUBMITTED AS PARTIAL REQUIREMENT FOR THE MASTERS OF ARTS IN RELIGIOUS STUDIES JOEL AMIS APRIL 2015 UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL Service des bibliothèques Avertissement La diffusion de ce mémoire se fait dans le respect des droits de son auteur, qui a signé le formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supérieurs (SDU-522 - Rév.01-2006) . Cette autorisation stipule que «conformément à l'article 11 du Règlement no 8 des études de cycles supérieurs, [l 'auteur] concède à l'Université du Québec à Montréal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalité ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pédagogiques et non commerciales. Plus précisément, [l 'auteur] autorise l'Université du Québec à Montréal à reproduire , diffuser, prêter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche à des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'Internet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entraînent pas une renonciation de [la] part [de l'auteur] à [ses] droits moraux ni à [ses] droits de propriété intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire, [l 'auteur] conserve la liberté de diffuser et de commercialiser ou non ce travail dont [il] possède un exemplaire. " UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC À MONTRÉAL LA NOUVELLE RELIGION JAPONAISE OOMOTO: RÉCONCILIATION DES COURANTS NATIVISTES ET INTERNATIONALISTES MÉMOIRE PRÉSENTÉE COMME EXIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAÎTRISE EN SCIENCES DES RELIGIONS JOEL AMIS AVRIL 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank the Oomoto organization rn general and the International Department ofüomoto in particular for graciously hosting us in Kameoka and other Oomoto centers and for all their eff01is to facilitate my research. -

The New Religious Sects of Japan

A Review Article THE NEW RELIGIOUS SECTS OF JAPAN by Shuteu Oishi The New Religions of Japan by Harry Thomsen, Tokyo, Japan and Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tattle Co” 1963, pp. 269,US $5.00 C VI,100)* Introduction The Nezv ReHg ons of Japan by Harry Thomsen is an unusually attractive, splendidly illustrated, and very interesting presentation of a subject about wh.ch there is a great deal of interest but very little factual knowledge. The Charles E. Tuttle Co.. the publisher, is to be commended for its unusually fine format. Since this is only the second volume in English to deal with the total situation, the book is certain to be read widely, and it wii! give the general reader a reasonably satisfactory overall picture of these modern sects. It is extremely unfortunate, however, that it is not as accurate and thoroughly reliable as it should be Had the manuscript been submitted to any ciie of a number of competent scholars in the field before publica tion, some of the more serious errors at least could have been eliminated. And some of the inconsistencies would have been avoided had more care been taken to incorporate last minute additions in the body of the text as well as merely at the end of some chapters. For example, P L Kvodiin is credited with * This book is available in Japan in paperback for ¥540. 一 45 — THE NEW RELIGIOUS SECTS OF JAPAN 600,000 believers on page 183 and 700,000 on page 197 ; and Daisaku Ikeda is only one of the Soka Gakkai leaders on page 100,but he is the tmrcl president on page 107. -

Tenrikyo Mission Headquarters of Hawai`I

Origins No. 253 September 2012 The 42nd Tenrikyo Bazaar Tenrikyo Mission Headquarters of Hawai`i ORIGINS, September 2012 TENRIKYO NEWSLETTER – ORIGINS AND MAKOTO MISSION STATEMENT To provide information related to Tenrikyo Hawaii services, activities, and events for the Tenrikyo community of Hawaii and for the people in the State of Hawaii. To inspire and initiate interest in having faith in religion, namely Tenrikyo, by conveying the Truth of the Jiba in words, in the manner and heart of God the Parent and Oyasama. Inside: • pg. 3 Message from the Head of the Overseas Department • pg. 4 August Monthly Service Prayer • pg. 5-10 August Monthly Service Sermon Island Life: • pg. 10-14 Hawaii Boys and Girls Association Children's Pilgrimage to Jiba Reflections • pg. 15 The 42nd Annual Tenrikyo Bazaar • pg. 16 Wedding and New Baby Born News Mission HQ Announcements • pg. 17 Tidbits • pg. 18-19 Hungry Reporter, Activity Calendar 2 ORIGINS, September 2012 Message from the Head of the Overseas Department August 26, Tenrikyo 175 I thank you deeply for your daily sincere efforts at each of your respective missions throughout the world. Even in the extreme summer heat at the Home of the Parent, many followers and friends of the path have returned, and the August Monthly Service was spiritedly performed with the Shinbashira as the core. In the service prayer, the Shinbashira stated that, “Step by step, the Parent, who began this world, will enter all of these useful timbers.” He emphasized we should keep these words in our heart and strive to saving others, so that we can spread the truth of all things to the entire world without lagging in construction of the Joyous World. -

Tenri Forum 2006 3 1A.Pdf

DAY THREE (July 17, 2006) Our Roles: Toward Making a Difference in the World Morning Session The Role of Tenrikyo in the World 3-1-1 Tenrikyo and Its Response to Medical Technology 3-1-2 Tenrikyo and Its Contribution to World Peace 3-1-3 Tenrikyo and Its Promotion of Cultural Activities 3-1-4 Tenrikyo and Its Approach to the Environment Regional Meetings Asia Africa/Europe/Oceania USA Northern California/Northwest/Canada USA East Coast/Midwest/South USA Southern California 3-1 Hawaii Latin America Japan 3-1 July 17th, Day Three Section Meetings Photo Gallery - Day Three Photo Gallery - 3-1-1 Tenrikyo and Medical Technology by speakers Mr. Kinoshita, Mr. Shiozawa, & Mr. Obayashi 3-1-2 Tenrikyo and World Peace by speakers Rev. Nagao, Mr. Itakura, & Mr. Komatsuzaki 3-1-3 Tenrikyo and Cultural Activities by speakers Mr. Yuge & Mr. Seldin 3-1-4 Tenrikyo and the Environment by speakers Ms. Dali, Mr. Noto, Mr. Forbes, & moderator Mr. Federowicz July 17th, Day Three Regional Meetings Photo Gallery Asia Africa, Europe, Oceania USA Northern California, Northwest, & Canada USA East Coast, Midwest, & South Southern California Hawaii Latin America Japan July 17th, Day Three Public Symposium Photo Gallery Tenrikyo’s Infl uence on Global, Social, and Economical Improvements by former Ambassador Nakamura Panel Discussion speakers (from left) Ms. Miyauchi, Rev. Takeuchi, and Rev. Yukimoto Panel Discussion Words of Encouragement by Rev. Iburi Tenri Forum Chairman Rev. Terada Participants of the Tenri Forum 2006 “New Frontiers in the Mission” Tenrikyo and Its Response to Medical Technology 3-1-1 Tenrikyo and Organ Transplantation Mikio Obayashi, M.D. -

Transactional Analysis in Psychotherapy

TThhee BBooookk ooff EEvvaann:: TThhee wwoorrkk aanndd lliiffee ooff EEvvaann MMccAArraa SShheerrrraarrdd Keith Tudor | Editor E-book edition The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Editor: Keith Tudor E-book (2020) ISBN: 9781877431–88-3 Printed edition (2017) ISBN: 9781877431-78-4 © Keith Tudor 2017, 2020 Keith Tudor asserts his moral right to be known as the Editor of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electrical, mechanical, photocopying, recording, digital or otherwise without the prior written permission of Resource Books Ltd. Waimauku, Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] | www.resourcebooks.co.nz Contents The Book of Evan: The work and life of Evan McAra Sherrard Keith Tudor | Editor Contents Foreword. Isabelle Sherrard Poroporoaki: A bridge between two worlds. Haare Williams Introduction to the e-book edition. Keith Tudor Introduction. Keith Tudor The organisation and structure of the book Acknowledgements References Part I. AGRICULTURE Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 1. Papers related to agriculture. Evan M. Sherrard Biology (2008) Film review of The Ground We Won (2015) References Chapter 2. Memories of Evan from Lincoln College and from a farm. Alan Nordmeyer, Robin Plummer, and Colin Wrennall Alan Nordmeyer writes Robin Plummer writes Colin Wrennall writes Part II. MINISTRY Introduction. Keith Tudor Chapter 3. Sermons. Evan M. Sherrard St. Patrick’s Day (1963) Sickness unto death (1965) Good grief (1966) When things get out of hand (1966) Rains or refugees? (1968) Unconscious influence (n.d.) Faithful winners (1998) Epiphany (2006) Colonialism (2008) Jesus and Paul — The consummate political activists (2009) A modern man faces Pentecost (2010) Ash Wednesday (2011) Healing (2011) Killed by a dancing girl (2012) Self-love (2012) Geering and Feuerbach (2014) Chapter 4. -

Tenri Journal of Religion

ISSN 0495-1492 TENRI JOURNAL OF RELIGION MARCH 2021 NUMBER 49 OYASATO INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGION TENRI UNIVERSITY TENRI UNIVERSITY PRESS TENRI, JAPAN © 2021 by Tenri University Press TENRI JOURNAL OF RELIGION MARCH 2021 NUMBER 49 CONTENTS Noriaki NAGAO : What It Means to Have a Dialogue with Others Towards the Realization of Peaceful Sociaty .............. 1 Yoshitsugu SAWAI : The Words of the Scriptures and Their Signifcance: From the Standpint of Tenrikyo Theology ........ 23 Takayuki ONOUE : Shōzen Nakayama’s 1933 North American Mission Tour and Japanese Immigrant Communities ...... 39 Book Review Yoshitsugu SAWAI : Michael Pye, ed., Exploring Shinto.................................71 The Contributors.............................................................................................75 Editor’s notes 1. Wherever possible, quotations from the Scriptures of Tenrikyo—the Ofudesaki (The Tip of the Writing Brush), the Mikagura-uta (The Songs for the Service), and the Osashizu (The Divine Directions)—are taken from the latest editions of the official translations provided by Tenrikyo Church Headquarters. In cases where the author cites material from the Osashizu that is not contained in offcially approved English-language sources such as Selections from the Osashizu, a trial translation prepared by the author or translator is used. 2.1. The Foundress of Tenrikyo, Miki Nakayama, is referred to by Tenrikyo followers as “Oyasama” and written as 教祖 in Japanese. 2.2. The Honseki ( 本席 ) or the Seki ( 席 ) refers to Izō Iburi, who delivered the Osashizu, the Divine Directions, and granted the Sazuke. 2.3. The one who governs Tenrikyo shall be the Shinbashira ( 真柱 ). The first Shinbashira was Shinnosuke Nakayama, the second Shinbashira Shōzen Nakayama, and the third Shinbashira Zenye Nakayama, who was succeeded in 1998 by Zenji Nakayama. -

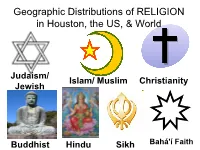

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World

Geographic Distributions of RELIGION in Houston, the US, & World Judaism/ Islam/ Muslim Christianity Jewish Buddhist Hindu Sikh Bahá'í Faith Learning Objectives, 109 slides • Overview of religious characteristics • Global and US distribution of religious people; Houston Interfaith Unity Council 3 • General demographic characteristics by religion: income, education 7 • Judaism / Jewish 26 • Islam / Muslims 49 • Hindus 80 • Sikhism 96 • Buddhist 103 Summary of Major Holidays & Celebrations by Religion FLDS Fundamentalist Latter Day Saints polygamy Christianity Christmas, Easter, Lent Buddhist Chinese New Year (lunar calendar) Hindu Holi – festival of colors (youth) Diwali – similar to Christmas Janmashtami – Goddess Lord Krishna (children) Jewish / Judaism Hanukah – similar to Christmas Passover – similar to Easter Rosh Hashanha – Jewish New Year Muslim / Islam Ramadan – month long fast with no food/water in daylight hours EID al Fitr – feast to break the fast Pilgrimage to The Hajj Major Religions of the World Folk Folk Christian Islam Buddhist & Chinese Hindu Christian Judaism Christian (Israel) Christian Sects within Major Religions Orthodox Christian Sunni Buddhist & Chinese Muslim Catholic Judaism (Israel) Orthodox Buddhist & Chinese Sunni Hindu Muslim Shia Muslim Catholic Christian Understanding the distribution of Catholics can help to predict location of the new Pope. Non-Religious % There are many parallels between religion and other social variables, in this case wealth and religiosity. more religious less religious Greater wealth -

Mission HQ June Monthly Service Sermon Rev. Audrey Nakagawa Head Minister of Lanai Church Today Is Father’S Day

Origins No. 299 July 2016 Hawaii Tenrikyo Students Association camp was held at Kahana Bay Beach Park from June 10 to 12. The program included morning & evening services, cleanup Hinokishin at the beach, and a Joy Workshop. The picture was taken after Bishop Yamanaka’s lecture. Tenrikyo Mission Headquarters of Hawaii 1 RELAY ESSAYS by Bishop & Mrs. Yamanaka & Board of Directors Takatoshi Mima In the concluding year towards Oyasama’s essence of our faith: 130th Anniversary, a book entitled “We are taught that God the Parent “Tenrikyo no Kangaekata, Kurashikata” created human beings and this world to (Tenrikyo Ways of Thinking and Living) see their Joyous Life and share in that was published by Doyusha. In this the editor joy. Thus, the Joyous Life is our final states his hope in the afterword of the book destination, which is beyond reasoning. as follows: The purpose of Tenrikyo is to lead people “In this book, 100 stories from “Tenrikyo to the Joyous Life from an individual level no Joshiki” (Tenrikyo’s Common Sense), to any level. So, can we live the Joyous Life which was published in series in the Tenri once we become Tenrikyo followers? The Jiho special issues between 1980 and answer can be both “Yes” and “No.” It can 1993, are selected and filed. Needless to be “Yes” because you can know the way to say, Oyasama’s teachings are the never the Joyous Life. However, it can be “No” changing truth. And Her course of life, because even though you may know the which She demonstrated by Her own way, you may not feel the Joyous Life right example is the Divine Model by which all away. -

Soka Gakkai's Human Revolution: the Rise of a Mimetic Nation in Modern

University of Hawai'i Manoa Kahualike UH Press Book Previews University of Hawai`i Press Fall 12-31-2018 Soka Gakkai’s Human Revolution: The Rise of a Mimetic Nation in Modern Japan Levi McLaughlin Follow this and additional works at: https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr Part of the Asian History Commons, Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation McLaughlin, Levi, "Soka Gakkai’s Human Revolution: The Rise of a Mimetic Nation in Modern Japan" (2018). UH Press Book Previews. 20. https://kahualike.manoa.hawaii.edu/uhpbr/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Hawai`i Press at Kahualike. It has been accepted for inclusion in UH Press Book Previews by an authorized administrator of Kahualike. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Soka Gakkai’s Human Revolution Contemporary Buddhism MARK M. ROWE, SERIES EDITOR Architects of Buddhist Leisure: Socially Disengaged Buddhism in Asia’s Museums, Monuments, and Amusement Parks Justin Thomas McDaniel Educating Monks: Minority Buddhism on China’s Southwest Border Thomas A. Borchert From the Mountains to the Cities: A History of Buddhist Propagation in Modern Korea Mark A. Nathan From Indra’s Net to Internet: Communication, Technology, and the Evolution of Buddhist Ideas Daniel Veidlinger Soka Gakkai’s Human Revolution: The Rise of a Mimetic Nation in Modern Japan Levi McLaughlin Soka Gakkai’s Human Revolution The Rise of a Mimetic Nation in Modern Japan Levi McLaughlin UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I PRESS HONOLULU © 2019 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: McLaughlin, Levi, author. -

CONFLICT and COMPROMISE in a JAPANESE VILLAGE by THORA

CONFLICT AND COMPROMISE IN A JAPANESE VILLAGE by THORA ELIZABETH HAWKEY B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1958 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF . MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology and -Sociology We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1963 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for.scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying, or publi• cation' of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology and Sociology The University of British Columbia,. Vancouver 8, Canada. Date May 6, 1963 ABSTRACT This study is based on field work done during a period of eight months when I lived in the Japanese farming village described in the paper. The project was carried out under the financial auspices of the Japanese Government. The religion Tenrikyo" is what I describe as a 'totalitarian' system. That is, it regulates the lives of its members.in all of their roles of life. The values and ideals of the religion emphasize the individual and his struggle to attain salvation. Each believer is expected to-devote himself and everything he owns to the final fullifiillment of the goals of Tenrikyo. -

2020 International Religious Freedom Report

CHINA (INCLUDES TIBET, XINJIANG, HONG KONG, AND MACAU) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Reports on Hong Kong, Macau, Tibet, and Xinjiang are appended at the end of this report. The constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which cites the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), states that citizens “enjoy freedom of religious belief” but limits protections for religious practice to “normal religious activities” without defining “normal.” CCP members and members of the armed forces are required to be atheists and are forbidden from engaging in religious practices. National law prohibits organizations or individuals from interfering with the state educational system for minors younger than the age of 18, effectively barring them from participating in most religious activities or receiving religious education. Some provinces have additional laws on minors’ participation in religious activities. The government continued to assert control over religion and restrict the activities and personal freedom of religious adherents that it perceived as threatening state or CCP interests, according to religious groups, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and international media reports. The government recognizes five official religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Islam, Protestantism, and Catholicism. Only religious groups belonging to one of the five state-sanctioned “patriotic religious associations” representing these religions are permitted to register with the government and officially permitted to hold worship services. There continued to be reports of deaths in custody and that the government tortured, physically abused, arrested, detained, sentenced to prison, subjected to forced indoctrination in CCP ideology, or harassed adherents of both registered and unregistered religious groups for activities related to their religious beliefs and practices.