Macsasaisrael10-71Opt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calvinism in the Context of the Afrikaner Nationalist Ideology

ASIAN AND AFRICAN STUDIES, 78, 2009, 2, 305-323 CALVINISM IN THE CONTEXT OF THE AFRIKANER NATIONALIST IDEOLOGY Jela D o bo šo vá Institute of Oriental Studies, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Klemensova 19, 813 64 Bratislava, Slovakia [email protected] Calvinism was a part of the mythic history of Afrikaners; however, it was only a specific interpretation of history that made it a part of the ideology of the Afrikaner nationalists. Calvinism came to South Africa with the first Dutch settlers. There is no historical evidence that indicates that the first settlers were deeply religious, but they were worshippers in the Nederlands Hervormde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church), which was the only church permitted in the region until 1778. After almost 200 years, Afrikaner nationalism developed and connected itself with Calvinism. This happened due to the theoretical and ideological approach of S. J.du Toit and a man referred to as its ‘creator’, Paul Kruger. The ideology was highly influenced by historical developments in the Netherlands in the late 19th century and by the spread of neo-Calvinism and Christian nationalism there. It is no accident, then, that it was during the 19th century when the mythic history of South Africa itself developed and that Calvinism would play such a prominent role in it. It became the first religion of the Afrikaners, a distinguishing factor in the multicultural and multiethnic society that existed there at the time. It legitimised early thoughts of a segregationist policy and was misused for political intentions. Key words: Afrikaner, Afrikaner nationalism, Calvinism, neo-Calvinism, Christian nationalism, segregation, apartheid, South Africa, Great Trek, mythic history, Nazi regime, racial theories Calvinism came to South Africa in 1652, but there is no historical evidence that the settlers who came there at that time were Calvinists. -

The Zacuto Complex: on Reading the Jews in South Africa

Richard Mendelsohn, Milton Shain. The Jews in South Africa: An Illustrated History. Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2008. x + 234 pp. $31.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-86842-281-4. Reviewed by Jonathan Judaken Published on H-Judaic (August, 2009) Commissioned by Jason Kalman (Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion) While the frst Jews to officially settle in South hand, Europeans colonized him in the name of Africa did so in the early nineteenth century, the the same basic ideas that justified European ex‐ history of their antecedents is much longer. They pansion and exploitation, notions that we can include Abraham ben Samuel Zacuto, distin‐ name in one word: racism. The "Zacuto complex," guished astronomer and astrologist at the Univer‐ as I want to call it, has played out through most of sity of Salamanca prior to the expulsion of the the history of Jews in South Africa, as this won‐ Jews from Spain in 1492. His astrological tables derful book demonstrates. were published in Hebrew, and then translated The Jews in South Africa, by two of the lead‐ into Latin, and then into Spanish. They were used ing living historians of South Africa’s Jewish past, by Christopher Columbus, and more importantly is the frst general history of South African Jewry by Vasco da Gama, for whom he also selected the in over ffty years. It is written in lively prose, scientific instruments and joined on his voyage to sumptuously illustrated, and includes rare photo‐ Africa.Zacuto, thereby, “was probably the frst Jew graphs as well as documents culled from the ar‐ to land on South African soil when, in mid-No‐ chives, which are inserted into offset “boxes” that vember 1497, the Da Gama party went ashore at help illuminate the forces at work in South St Helena Bay on the Cape west coast” (p. -

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020 The Dissertation Committee for John Michael Meyer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation. One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) Committee: Ami Pedahzur, Supervisor Zoltan D. Barany David M. Buss William Roger Louis Thomas G. Palaima Paul B. Woodruff One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) by John Michael Meyer Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis who guided me on this endeavor from start to finish and To Lorna Paterson Wingate Smith. Acknowledgements Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis have helped me immeasurably throughout my time at the University of Texas, and I wish that everyone could benefit from teachers so rigorous and open minded. I will never forget the compassion and strength that they demonstrated over the course of this project. Zoltan Barany developed my skills as a teacher, and provided a thoughtful reading of my first peer-reviewed article. David M. Buss kept an open mind when I approached him about this interdisciplinary project, and has remained a model of patience while I worked towards its completion. My work with Tom Palaima and Paul Woodruff began with collaboration, and then moved to friendship. Inevitably, I became their student, though they had been teaching me all along. -

TITLE the Implementation of the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate in Palestine: Proble

https://research.stmarys.ac.uk/ TITLE The implementation of the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate in Palestine: problems of conquest and colonisation at the nadir of British Imperialism (1917–1936) AUTHOR Regan, Bernard DATE DEPOSITED 13 April 2016 This version available at https://research.stmarys.ac.uk/id/eprint/1009/ COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Archive makes this work available, in accordance with publisher policies, for research purposes. VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. For citation purposes, please consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication. The Implementation of the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate in Palestine: problems of con- quest and colonisation at the nadir of British Imperi- alism (1917–1936) Regan, Bernard (2016) The Implementation of the Balfour Dec- laration and the British Mandate in Palestine: problems of con- quest and colonisation at the nadir of British Imperialism (1917– 1936) University of Surrey Version: PhD thesis Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individ- ual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open- Research Archive’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult http:// research.stmarys.ac.uk/policies.html http://research.stmarys.ac.uk/ The Implementation of the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate in Palestine: problems of conquest and colonisation at the nadir of British Imperialism (1917–1936) Thesis submitted by Bernard Regan For the award of Doctor of Philosophy School of Arts and Humanities University of Surrey January 2016 ©Bernard Regan 2016 1 Summary The objective of this thesis is to analyse the British Mandate in Palestine with a view to developing a new understanding of the interconnections and dissonances between the principal agencies. -

Institutionalising Diaspora Linkage the Emigrant Bangladeshis in Uk and Usa

Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employmwent INSTITUTIONALISING DIASPORA LINKAGE THE EMIGRANT BANGLADESHIS IN UK AND USA February 2004 Ministry of Expatriates’ Welfare and Overseas Employment, GoB and International Organization for Migration (IOM), Dhaka, MRF Opinions expressed in the publications are those of the researchers and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an inter-governmental body, IOM acts with its partners in the international community to: assist in meeting the operational challenges of migration; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and work towards effective respect of the human dignity and well-being of migrants. Publisher International Organization for Migration (IOM), Regional Office for South Asia House # 3A, Road # 50, Gulshan : 2, Dhaka : 1212, Bangladesh Telephone : +88-02-8814604, Fax : +88-02-8817701 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : http://www.iow.int ISBN : 984-32-1236-3 © [2002] International Organization for Migration (IOM) Printed by Bengal Com-print 23/F-1, Free School Street, Panthapath, Dhaka-1205 Telephone : 8611142, 8611766 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. -

'Coloured' People of South Africa

Bertie Neethling Durban University of Technology (DUT) Durban Introduction : Population of South Africa 57 million people (Statistics South Africa 2018) Cohort-component method: base population is estimated being consistent with known demographic characteristics Many prefer being called a ‘South African/a Zulu speaking South African/an English speaking South African’ Government uses 4 categories: Black (African), Coloured, White, Indian/Asian – smaller groups not recognised Black (African) 80,5%, Coloured 8,8%, White 8,3% Indian/Asian: much smaller Coloured: nearly 5 million History of the so-called Coloureds History of multicultural and multilingual SA is complex Controversy: First People in south around Cape Town before colonialism First World people: hunter-gatherers roaming around – San and Khoi Dutch explorers – VOIC – Jan van Riebeeck (1652) Slaves imported: Batavia, Madagascar, Indonesia, India, Angola, Mozambique Combination and interaction: Khoi and San, Dutch white settlers, slave groups, finally British colonialists Mixed group (mainly excluding Khoi, San and Dutch: Coloureds Lack of accurate historical data and suitable ethnic term Present-day Coloureds Cape Coloureds – bilingual –Afrikaans/English Term ‘Coloured’ i.e. ‘person of colour’ (Afr. ‘Kleurling’) – nonsensical term 2008 ‘Bruin Belange Inisiatief’ – Dr. Danny Titus Term ‘Coloured’/’Kleurling’ fixed – ethnic group of mixed descent – various combinations - confusion No accurate ancestry Names from students, newspaper, school photo’s, random reports of groups or individuals – post1994 Identity Challenges June 1926: ‘Can any man commit a greater crime than be born Coloured in South Africa? – RDM If assigned to this group, specific lifestyles were invented, bonding into a community – considered problematic 2009 I’m not Black, I’m Coloured – Identity crisis at the Cape of Good Hope (Monde World Films) Song: …the only sin, is the colour of my skin. -

INDIAN CULTURE ‘ in the ELECTRONIC MEDIA: a Case Study of ‘Impressions’

PORTRAYAL OF ‘INDIAN CULTURE ‘ IN THE ELECTRONIC MEDIA: A Case Study of ‘Impressions’ By Saijal Gokool _____________________________________________________________ Author: Saijal Gokool Place: Durban Date: 1994 Product: MA Thesis Copyright: Centre for Cultural and Media Studies, University of Natal. ____________________________________________________________ Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere thanks to all those who assisted me with my research. Special mention needs to be made of the executive producer of Impressions Mr Ramu Gopidayal and other cultural leaders for their generous time. To Dr Ruth Tomaselli and Professor Keyan Tomaselli, I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to you for your guidance during my year at the Centre for Cultural and Media Studies. Special acknowledgements are due to my parents and my brother and sister, for their patience and understanding and without whose support I would not have made it through the year. I should like to add a very special thank you to my father for the support, advice and encouragement he has always given me. Abstract The idea the South African Indian community as a homogenous has derived from the apartheid ideology of separate development. From the time of their arrival in 1980, indentured labourer has endured a series of processes that have shaped the deve1opment of this ethnic minority. With the determination to belong and endure at any cost, the South A frican Indian celebrated 134 years in South Africa on the 16th of November 1994. In 1987, the introduction of a two-hour ethnic broadcast by the South African Broadcasting Corporation, to cater for the Indian community in South Africa seen as a means to 'satisfy a need' of the community. -

Israel's Rights As a Nation-State in International Diplomacy

Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Institute for Research and Policy המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( ISRAEl’s RiGHTS as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy Israel’s Rights as a Nation-State in International Diplomacy © 2011 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs – World Jewish Congress Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai Street, Jerusalem, Israel Tel. 972-2-561-9281 Fax. 972-2-561-9112 Email: [email protected] www.jcpa.org World Jewish Congress 9A Diskin Street, 5th Floor Kiryat Wolfson, Jerusalem 96440 Phone : +972 2 633 3000 Fax: +972 2 659 8100 Email: [email protected] www.worldjewishcongress.com Academic Editor: Ambassador Alan Baker Production Director: Ahuva Volk Graphic Design: Studio Rami & Jaki • www.ramijaki.co.il Cover Photos: Results from the United Nations vote, with signatures, November 29, 1947 (Israel State Archive) UN General Assembly Proclaims Establishment of the State of Israel, November 29, 1947 (Israel National Photo Collection) ISBN: 978-965-218-100-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Overview Ambassador Alan Baker .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 The National Rights of Jews Professor Ruth Gavison ........................................................................................................................................................................... 9 “An Overwhelmingly Jewish State” - From the Balfour Declaration to the Palestine Mandate -

A Profile of the Western Cape Province: Demographics, Poverty, Inequality and Unemployment

Background Paper Series Background Paper 2005:1(1) A profile of the Western Cape province: Demographics, poverty, inequality and unemployment Elsenburg August 2005 Overview The Provincial Decision-Making Enabling (PROVIDE) Project aims to facilitate policy design by supplying policymakers with provincial and national level quantitative policy information. The project entails the development of a series of databases (in the format of Social Accounting Matrices) for use in Computable General Equilibrium models. The National and Provincial Departments of Agriculture are the stakeholders and funders of the PROVIDE Project. The research team is located at Elsenburg in the Western Cape. PROVIDE Research Team Project Leader: Cecilia Punt Senior Researchers: Kalie Pauw Melt van Schoor Young Professional: Bonani Nyhodo Technical Expert: Scott McDonald Associate Researchers: Lindsay Chant Christine Valente PROVIDE Contact Details Private Bag X1 Elsenburg, 7607 South Africa [email protected] +27-21-8085191 +27-21-8085210 For the original project proposal and a more detailed description of the project, please visit www.elsenburg.com/provide PROVIDE Project Background Paper 2005:1(1) August 2005 A profile of the Western Cape province: Demographics, poverty, inequality and unemployment 1 Abstract This paper forms part of a series of papers that present profiles of South Africa’s provinces, with a specific focus on key demographic statistics, poverty and inequality estimates, and estimates of unemployment. In this volume comparative statistics are presented for agricultural and non-agricultural households, as well as households from different racial groups, locations (metropolitan, urban and rural areas) and district municipalities of the Western Cape. Most of the data presented are drawn from the Income and Expenditure Survey of 2000 and the Labour Force Survey of September 2000, while some comparative populations statistics are extracted from the National Census of 2001 (Statistics South Africa). -

Old Comrade Crafts a Fine Memory of Our Past

Old comrade crafts a fine memory of our past Memory against Forgetting: Memoirs Now he re-visits us, ever the ana Govan Mbeki and others, stood ac from a Life in South African Politics lyst, theoretician, activist, the stimu cused at the Rivonia Trial. Following 1938-1964 lating and helpful companion. Again the petty-minded and vindictive fic by Rusty Bernstein (Viking) R128 he fires my insurrectionary imagi tions presented by the prosecution, nation, as, surely, he will ignite those he alone among his comrades was Review: Alan Lipman who treat themselves to this quietly acquitted. Isolated and depressed he didactic book. bowed to the now urgent need for es Among the facets of a sustained cape into exile with his family. his is a finely crafted vol political life which Bernstein illumi If there is a need for the feminist ume: the lucid, analytic nates, the most constant is his contention that “the personal is po record of someone who propensity for incisive analysis, for litical” to be affirmed, this book does was engaged, who was em epitom ising EM Forster’s memo so. Despite the author’s reticence beddedT in the politics of South rable invitation, “only connect”. about such matters, one is reminded African resistance from the late- This is a pervasive thread, repeatedly, and always poignantly, of 1930s to the 1960s. If on entering a through events leading to and sur the effects of his wife’s and his en new century, you wish to touch the rounding the post-1948 Votes for All forced separations from their four core of those momentous decades, assembly and the Suppression of children, from each other. -

A Rhetorical History of the British Constitution of Israel, 1917-1948

A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION OF ISRAEL, 1917-1948 by BENJAMIN ROSWELL BATES (Under the Direction of Celeste Condit) ABSTRACT The Arab-Israeli conflict has long been presented as eternal and irresolvable. A rhetorical history argues that the standard narrative can be challenged by considering it a series of rhetorical problems. These rhetorical problems can be reconstructed by drawing on primary sources as well as publicly presented texts. A methodology for doing rhetorical history that draws on Michael Calvin McGee's fragmentation thesis is offered. Four theoretical concepts (the archive, institutional intent, peripheral text, and center text) are articulated. British Colonial Office archives, London Times coverage, and British Parliamentary debates are used to interpret four publicly presented rhetorical acts. In 1915-7, Britain issued the Balfour Declaration and the McMahon-Hussein correspondence. Although these documents are treated as promises in the standard narrative, they are ambiguous declarations. As ambiguous documents, these texts offer opportunities for constitutive readings as well as limiting interpretations. In 1922, the Mandate for Palestine was issued to correct this vagueness. Rather than treating the Mandate as a response to the debate between realist foreign policy and self-determination, Winston Churchill used epideictic rhetoric to foreclose a policy discussion in favor of a vote on Britain's honour. As such, the Mandate did not account for Wilsonian drives in the post-War international sphere. After Arab riots and boycotts highlighted this problem, a commission was appointed to investigate new policy approaches. In the White Paper of 1939, a rhetoric of investigation limited Britain's consideration of possible policies. -

V Ie Lò Ie VJ-Arcló

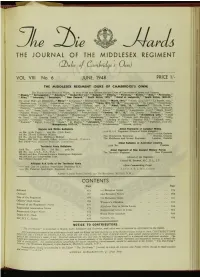

Vie lòie VJ-arcló THE JOURNAL OF THE MIDDLESEX REGIMENT a ule of* C^amlridÿe S O w n ) VOL. VIII. No. 6 JUNE, 1948 PRICE 1/- THE MIDDLESEX REGIMENT (DUKE OF CAMBRIDGE'S OWN) (57) The Plume of the Prince of Wales. In each of the four comers the late Duke of Cambridge's Cypher and Coronet. ** Mysore,” “ Seringapatam," “ Albuhera,” “ Ciudad Rod-iço,” “ Badajoz,” “ Vittoria,” “ Pyrenees,” “ Nivelle,” “ Nive,” “ Peninsular,” "Alma,” “ Inkerman,” “Sevastopol,” “ New Zealand,” “ South Africa, 1879,” "Relief of Ladysmith,” “ South Africa, 1900-02." The Great War—46 Battalions— “ Mons,” " Le Cateau,” “ Retreat from Mons,” “ Marne, 1914,” “ Aisne, 1014. ’18,” “ La Bassèe, 1914,” “ Messines, 1014, T~. TS,” " Armentières, 1914,” “ Neuve Chapelle,” “ Ypres, 1915, '17, ’18,” *' Gravenstafel,” “ St. Julien," “ Frezenbere." “ Bellewaarde.” " Aubers,” “ Hooge, 1915," “ Loos.” “ Somme, 1916, '18,” “ Albert, 1916, ’18,” “ Baz enfin,” " Delville Wood.' “ Pozières,” " Ginchy,” “ Flers-Courcelette,” “ Morval,” “ Thiepval," “ Le Transloy,” “ Ancre Heights," “ Ancre, 1916, ’iS," “ Bapaume, 1917, TS," “ Arras, 1017, ’18," " Vimy, 1917,” " Scarpe, 1917, ’18,” " Arleux," ** Pilckem,” “ Langemarck, 1917,” " Menin Road," “ Polvgon Wood,” “ Broodseinde,” " Poelcappelle,” “ Passchendaele,” “ Cambrai, 1917, ’18,” " St. Quentin," " Rosières," " Avre," “ Villers Bretonneux.” “ Lys,” " Estaires,” “ Hazebrouck,” “ Bailleul,” " Kemmel,” " Scherpenberg.” “ Hindenburg Line,” ** Canal du Nord,” "St. Quentin Canal,” “ Courtrai," “ Selle,” "Valenciennes,” “ Sambre,” “ France and Flanders, 1014-1S.“ “ Italy, 1917-18,” “ Struma,” “ Doiran, 1918,” “ Macedonia, 1915-18,” " Suvla,” “ Landing at Suvia," “ Scimitar Hill,” “ Gallipoli, 1915.'* " Rumani," "Egypt, 1915-17,” “ Gaza,” “ El Mughar,” “ Jerusalem,” "Jericho,” “ Jordan,” “ Tell 'Asur." "Palestine, 1017-18,' “ Mesopotamia, 1917-18, * " Murman, 1919»" “ Dukhovskaya," " Siberia, 1918-19.” Regular and Militia Battalions. Allied Regiments of Canadian Militia. 1st Bn. (57th Foot). 2nd Bn. (77th Foot).