JSP 839 Climatic Injuries in the Armed Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEBRUARY 2012 ISSUE No

MILITARY AVIATION REVIEW FEBRUARY 2012 ISSUE No. 291 EDITORIAL TEAM COORDINATING EDITOR - BRIAN PICKERING WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL”[email protected]” BRITISH REVIEW - GRAEME PICKERING 15 ASH GROVE, BOURNE, LINCS PE10 9SG TEL NO. 01778 421788 EMail "[email protected]" FOREIGN FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (see Co-ordinating Editor above for address details) US FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (COORDINATING) (see above for address details) STATESIDE: MORAY PICKERING 18 MILLPIT FURLONG, LITTLEPORT, ELY, CAMBRIDGESHIRE, CB6 1HT E Mail “[email protected]” EUROPE: BRIAN PICKERING OUTSIDE USA: BRIAN PICKERING See address details above OUT OF SERVICE - ANDY MARDEN 6 CAISTOR DRIVE, BRACEBRIDGE HEATH, LINCOLN LN4 2TA E-MAIL "[email protected]" MEMBERSHIP/DISTRIBUTION - BRIAN PICKERING MAP, WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL.”[email protected]” ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION (Jan-Dec 2012) UK £40 EUROPE £48 ELSEWHERE £50 @MAR £20 (EMail/Internet Only) MAR PDF £20 (EMail/Internet Only) Cheques payable to “MAP” - ALL CARDS ACCEPTED - Subscribe via “www.mar.co.uk” ABBREVIATIONS USED * OVERSHOOT f/n FIRST NOTED l/n LAST NOTED n/n NOT NOTED u/m UNMARKED w/o WRITTEN OFF wfu WITHDRAWN FROM USE n/s NIGHTSTOPPED INFORMATION MAY BE REPRODUCED FROM “MAR” WITH DUE CREDIT EDITORIAL - Welcome to the February edition of MAR! This issue sees the United Kingdom 2012 Review from Graeme - a month later than usual due to his work commitments. Because of this the issue is somewhat truncated in the Foreign Section department, but we should catch up with the March issue. -

Premises, Sites Etc Within 30 Miles of Harrington Museum Used for Military Purposes in the 20Th Century

Premises, Sites etc within 30 miles of Harrington Museum used for Military Purposes in the 20th Century The following listing attempts to identify those premises and sites that were used for military purposes during the 20th Century. The listing is very much a works in progress document so if you are aware of any other sites or premises within 30 miles of Harrington, Northamptonshire, then we would very much appreciate receiving details of them. Similarly if you spot any errors, or have further information on those premises/sites that are listed then we would be pleased to hear from you. Please use the reporting sheets at the end of this document and send or email to the Carpetbagger Aviation Museum, Sunnyvale Farm, Harrington, Northampton, NN6 9PF, [email protected] We hope that you find this document of interest. Village/ Town Name of Location / Address Distance to Period used Use Premises Museum Abthorpe SP 646 464 34.8 km World War 2 ANTI AIRCRAFT SEARCHLIGHT BATTERY Northamptonshire The site of a World War II searchlight battery. The site is known to have had a generator and Nissen huts. It was probably constructed between 1939 and 1945 but the site had been destroyed by the time of the Defence of Britain survey. Ailsworth Manor House Cambridgeshire World War 2 HOME GUARD STORE A Company of the 2nd (Peterborough) Battalion Northamptonshire Home Guard used two rooms and a cellar for a company store at the Manor House at Ailsworth Alconbury RAF Alconbury TL 211 767 44.3 km 1938 - 1995 AIRFIELD Huntingdonshire It was previously named 'RAF Abbots Ripton' from 1938 to 9 September 1942 while under RAF Bomber Command control. -

Features: RAF100 Steam Challenge • RAF100 Parade in Leicester • Wittfest Success • Community Support

TITLE OF ARTICLE SECTION HEADING Autumn 2018 Autumn WitteringThe official magazine for RAF Wittering and the A4 Force View AUTUMN 2018 WITTERING VIEW 1 Features: RAF100 Steam Challenge • RAF100 Parade in Leicester • WittFest Success • Community Support SECTION HEADING TITLE OF ARTICLE Editor Welcome to the autumn edition of the Wittering View. It doesn’t seem so long ago that I was introducing my first edition. I’m sure most of us have the same impression with the high tempo of Foreword work going on around the Unit. The main feature continues with proving powerful, and is helping the celebration of the RAF Centenary. In what has been a remarkable year for us to make informed decisions RAF Wittering personnel have been the Royal Air Force, Wittering continues to that better take account of involved in a vast array of events in the needs of our people. I was support of RAF100. A fascinating article focus on its dual roles of being the home of particularly proud to see the about the Steam Challenge on page Shadow Board engage with the 12 demonstrates the diversity involved specialist engineering and logistics capabilities Chief of the Air Staff and members in the events. We also have more on of the Air Force Board Executive the Baton Relay on page 13, with more under the command of the A4 Force, while Committee during their recent coverage of the significant RAF100 also providing a safe aerodrome at which the visit to the Station and, more event in London on page 16. The importantly, heartened to see the support from 2 MT Sqn can be read on next generation of military pilots learn to fly. -

82Nd AIRBORNE NORMANDY 1944

82nd AIRBORNE NORMANDY 1944 Steven Smith Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2017 by CASEMATE PUBLISHERS 1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083 and 10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford, OX1 2EW Copyright 2017 © Simon Forty ISBN-13: 978-1-61200-536-2 eISBN-13: 978-1-61200-537-9 Mobi ISBN-13: 978-1-61200-537-9 Produced by Greene Media Ltd. Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress and the British Library. All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purposes of review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission from the Publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the Authors or Publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details. All Internet site information provided was correct when received from the Authors. The Publisher can accept no responsibility for this information becoming incorrect. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact: CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US) Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146 E-mail: [email protected] CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK) Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgments Most of the photos are US Signal Corps images that have come from a number of sources. -

Their Stories

NORTH YORKSHIRE’S UNSUNG HEROES THEIR STORIES Acknowledgements We are indebted to the men and women who have given their time to share their valuable stories and kindly allowed us to take copies of their personal photographs. We are also extremely grateful to them for allowing their personal histories to be recorded for the benefit of current and future generations. In addition, we would like to thank Dr Tracy Craggs, who travelled the length and breadth of North Yorkshire to meet with each of the men and women featured in this book to record their stories. We would also like to thank her – on behalf of the Unsung Heroes – for her time, enthusiasm and kindness. © Copyright Community First Yorkshire, 2020 All rights reserved. The people who have shared their stories for this publication have done so with the understanding that they will not be reproduced without prior permission of the publisher. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction will constitute an infringement of copyright. Contents Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Their stories 5 – 45 Glossary 46 NORTH YORKSHIRE’S UNSUNG HEROES I THEIR STORIES Foreword North Yorkshire has a strong military history and a continuing armed forces presence. The armed forces are very much part of our local lives – whether it’s members of our own families, the armed forces’ friends in our children’s schools, the military vehicles on the A1, or the jets above our homes. The serving armed forces are visible in our county – but the older veterans, our unsung heroes, are not necessarily so obvious. With the Ex-Forces Support North Yorkshire project we wanted to raise the profile of older veterans across North Yorkshire. -

Four Decades Airfield Research Group Magazine

A IRFIELD R ESEARCH G ROUP M AGAZINE . C ONTENTS TO J UNE 2017 Four Decades of the Airfield Research Group Magazine Contents Index from December 1977 to June 2017 1 9 7 7 1 9 8 7 1 9 9 7 6 pages 28 pages 40 pages © Airfield Research Group 2017 2 0 0 7 2 0 1 7 40 pages Version 2: July 2017 48 pages Page 1 File version: July 2017 A IRFIELD R ESEARCH G ROUP M AGAZINE . C ONTENTS TO J UNE 2017 AIRFIELD REVIEW The Journal of the Airfield Research Group The journal was initially called Airfield Report , then ARG Newsletter, finally becoming Airfield Review in 1985. The number of pages has varied from initially just 6, occasio- nally to up to 60 (a few issues in c.2004). Typically 44, recent journals have been 48. There appear to have been three versions of the ARG index/ table of contents produced for the magazine since its conception. The first was that by David Hall c.1986, which was a very detailed publication and was extensively cross-referenced. For example if an article contained the sentence, ‘The squadron’s flights were temporarily located at Tangmere and Kenley’, then both sites would appear in the index. It also included titles of ‘Books Reviewed’ etc Since then the list has been considerably simplified with only article headings noted. I suspect that to create a current cross-reference list would take around a day per magazine which equates to around eight months work and is clearly impractical. The second version was then created in December 2009 by Richard Flagg with help from Peter Howarth, Bill Taylor, Ray Towler and myself. -

To Rutland Record 21-30

Rutland Record Index of numbers 21-30 Compiled by Robert Ovens Rutland Local History & Record Society The Society is formed from the union in June 1991 of the Rutland Local History Society, founded in the 1930s, and the Rutland Record Society, founded in 1979. In May 1993, the Rutland Field Research Group for Archaeology & History, founded in 1971, also amalgamated with the Society. The Society is a Registered Charity, and its aim is the advancement of the education of the public in all aspects of the history of the ancient County of Rutland and its immediate area. Registered Charity No. 700723 The main contents of Rutland Record 21-30 are listed below. Each issue apart from RR25 also contains annual reports from local societies, museums, record offices and archaeological organisations as well as an Editorial. For details of the Society’s other publications and how to order, please see inside the back cover. Rutland Record 21 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 31 9 Letters of Mary Barker (1655-79); A Rutland association for Anton Kammel; Uppingham by the Sea – Excursion to Borth 1875-77; Rutland Record 22 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 32 7 Obituary – Prince Yuri Galitzine; Returns of Rutland Registration Districts to 1851 Religious Census; Churchyard at Exton Rutland Record 23 (£2.50, members £2.00) ISBN 978 0 907464 33 4 Hoard of Roman coins from Tinwell; Medieval Park of Ridlington;* Major-General Lord Ranksborough (1852-1921); Rutland churches in the Notitia Parochialis 1705; John Strecche, Prior of Brooke 1407-25 -

Flying As a Career Professional Pilot Training

SO YOU WANT TO BE A PILOT? 2009 Flying As A Career Professional Pilot Training Author Captain Ralph KOHN FRAeS GUILD OF AIR PILOTS ROYAL AERONAUTICAL AND NAVIGATORS SOCIETY A Guild of the City of London At the forefront of change Founded in 1929, the Guild is a Livery Company of the City of Founded in 1866 to further the science of aeronautics, the Royal London. It received its Letters Patent in 1956. Aeronautical Society has been at the forefront of developments in aerospace ever since. Today the Society performs three primary With as Patron His Royal Highness The Prince Philip, Duke of roles: Edinburgh, KG KT and as Grand Master His Royal Highness The • to support and maintain the highest standards for Prince Andrew, Duke of York, CVO ADC, the Guild is a charitable professionalism in all aerospace disciplines; organisation that is unique amongst City Livery Companies in • to provide a unique source of specialist information and a having active regional committees in Australia, Canada, Hong central forum for the exchange of ideas; Kong and New Zealand. • To exert influence in the interests of aerospace in both the public and industrial arenas. Main objectives • To establish and maintain the highest standards of air safety through the promotion of good airmanship among air pilots Benefits • Membership grades for professionals and enthusiasts alike and air navigators. • Over 17,000 members in more than 100 countries • To maintain a liaison with all authorities connected with licensing, training and legislation affecting pilot or navigator • An International network of 70 Branches whether private, professional, civil or military. -

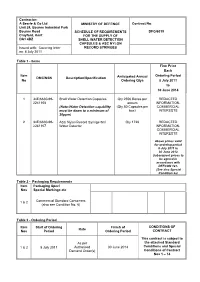

Name & Address Of

Contractor: A Searle & Co Ltd MINISTRY OF DEFENCE Contract No: Unit 24, Bourne Industrial Park Bourne Road SCHEDULE OF REQUIREMENTS DFG/6019 Crayford, Kent FOR THE SUPPLY OF DA1 4BZ SHELL WATER DETECTION CAPSULES & ASC NYLON Issued with: Covering letter RECORD SYRINGES on: 8 July 2011 Table 1 - Items Firm Price Each Item Ordering Period DMC/NSN Description/Specification Anticipated Annual No Ordering Qtys 8 July 2011 to 30 June 2014 1 34E/6630-99- Shell Water Detection Capsules Qty 2556 Boxes per REDACTED 2241108 annum INFORMATION- (Note-Water Detection capability (Qty 80 Capsules per COMMERCIAL must be down to a minimum of box) INTERESTS 30ppm) 2 34E/6630-99- ASC Nylon Record Syringe 5ml Qty 1728 REDACTED 2241107 Water Detector INFORMATION- COMMERCIAL INTERESTS Above prices valid for ordering period 8 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. Subsequent prices to be agreed in accordance with DEFCON 127. (See also Special Condition 2a) Table 2 - Packaging Requirements Item Packaging Spec/ Nos Special Markings etc Commercial Standard Containers 1 & 2 (also see Condition No. 6) Table 3 - Ordering Period Item Start of Ordering Finish of CONDITIONS OF Rate Nos Period Ordering Period CONTRACT This contract is subject to As per the attached Standard 1 & 2 8 July 2011 Authorised 30 June 2014 Conditions and Special Demand Order(s) Conditions of Contract Nos 1 – 14 DFG/6019 STANDARD CONDITIONS OF CONTRACT The following Defence Conditions (DEFCONs) shall apply: DEFCON 5 (Edn 07/99) - MOD Forms 640 – Advice and Inspection Note DEFCON 5J (Edn 07/08) - Unique Identifiers DEFCON 68 (Edn 05/10) - Supply of Hazardous Articles and Substances DEFCON 76 (Edn 12/06) - Contractor’s Personnel at Government Establishments DEFCON 127 (Edn 10/04) - Price Fixing Condition for Contracts of Lesser Value DEFCON 129 (Edn 07/08) - Packaging (For Articles other than Ammunition and Explosives) – see also Condition No 6 Note: For the purposes of this Contract Clause 12 - Spares Price Labelling is not applicable. -

Flightlines JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018

Saturday April 28, 2018 LIVE & SILENT AUCTION BUY TICKETS NOW!! SAVE+WIN!! EARLY BUY DEAL $3999 $29999 (until March 31st) per person OR table of 8 includes chance for trip prize - reg. $49.99 reg. $399.99 All tickets to this casual event include buffet dinner & wine. Amazing Prizes to be Won including a Private Tour of Jay Leno’s Personal Garage* *Items subject to change without notice. 9280 Airport Road Mount Hope, Ontario, L0R 1W0 warplane.com Fundraiser supporting the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum plus Help A Child Smile President & Chief Executive Officer David G. Rohrer Vice President – Facilities Manager Controller Operations Cathy Dowd Brenda Shelley Pam Rickards Curator Education Services Vice President – Finance Erin Napier Manager Ernie Doyle Howard McLean Flight Coordinator Chief Engineer Laura Hassard-Moran Donor Services Jim Van Dyk Manager Retail Manager Sally Melnyk Marketing Manager Shawn Perras Al Mickeloff Building Maintenance Volunteer Services Manager Food & Beverage Manager Administrator Jason Pascoe Anas Hasan Toni McFarlane Board of Directors Christopher Freeman, Chair Nestor Yakimik Art McCabe David Ippolito Robert Fenn Dennis Bradley, Ex Officio John O’Dwyer Marc Plouffe Sandy Thomson, Ex Officio David G. Rohrer Patrick Farrell Bruce MacRitchie, Ex Officio Stay Connected Subscribe to our eFlyer Canadian Warplane warplane.com/mailing-list-signup.aspx Heritage Museum 9280 Airport Road Read Flightlines online warplane.com/about/flightlines.aspx Mount Hope, Ontario L0R 1W0 Like us on Facebook facebook.com/Canadian Phone 905-679-4183 WarplaneHeritageMuseum Toll free 1-877-347-3359 (FIREFLY) Fax 905-679-4186 Follow us on Twitter Email [email protected] @CWHM Web warplane.com Watch videos on YouTube youtube.com/CWHMuseum Shop our Gift Shop warplane.com/gift-shop.aspx Follow Us on Instagram instagram.com/ canadianwarplaneheritagemuseum Volunteer Editor: Bill Cumming Flightlines is the official publication of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. -

Raf Canberra Units of the Cold War

0413&:$0.#"5"*3$3"'5t RAF CANBERRA UNITS OF THE COLD WAR Andrew Brookes © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com SERIES EDITOR: TONY HOLMES OSPREY COMBAT AIRCRAFT 105 RAF CANBERRA UNITS OF THE COLD WAR ANDREW BROOKES © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE IN THE BEGINNING 6 CHAPTER TWO BINBROOK AND BEYOND 11 CHAPTER THREE TRAINING DAYS 16 CHAPTER FOUR PHOTOGRAPHIC MEMORIES 26 CHAPTER FIVE THE SUEZ CAMPAIGN 41 CHAPTER SIX GOING NUCLEAR 54 CHAPTER SEVEN MIDDLE EAST AND FAR EAST 62 CHAPTER EIGHT RAF GERMANY 78 CHAPTER NINE ULTIMATE PR 9 85 APPENDICES 93 COLOUR PLATES COMMENTARY 94 INDEX 96 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com IN THE BEGINNING CHAPTER ONE n 1 March 1943, more than 250 four-engined RAF bombers O dropped 600 tons of bombs on Berlin. Following the raid 500 large fires raged out of control, 20,000 homes were damaged, 35,000 people were rendered homeless and 700 civilians were killed. The following day, a photo-reconnaissance Mosquito circled high over Hitler’s capital taking damage assessment photographs in broad daylight. Neither German fighters nor flak could touch it. The versatile de Havilland Mosquito was designed to operate higher and faster than the opposing air defences. In Lancashire, the company known as English Electric (EE) could only gaze in wonder at the de Havilland creation. In 1938, as part of the huge re-equipment programme for the RAF, EE’s Preston factory received contracts to build the Handley Page Hampden medium bomber. After 1941 the Preston facility turned out 2145 Halifax bombers, while also building a flight test airfield at Samlesbury, a few miles away. -

Raaf Personnel Serving on Attachment in Royal Air Force Squadrons and Support Units

Cover Design by: 121Creative Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6012 email. [email protected] www.121creative.com.au Printed by: Kwik Kopy Canberra Lower Ground Floor, Ethos House, 28-36 Ainslie Pl, Canberra ACT 2601 phone. (02) 6243 6066 email. [email protected] www.canberra.kwikkopy.com.au Compilation Alan Storr 2006 The information appearing in this compilation is derived from the collections of the Australian War Memorial and the National Archives of Australia. Author : Alan Storr Alan was born in Melbourne Australia in 1921. He joined the RAAF in October 1941 and served in the Pacific theatre of war. He was an Observer and did a tour of operations with No 7 Squadron RAAF (Beauforts), and later was Flight Navigation Officer of No 201 Flight RAAF (Liberators). He was discharged Flight Lieutenant in February 1946. He has spent most of his Public Service working life in Canberra – first arriving in the National Capital in 1938. He held senior positions in the Department of Air (First Assistant Secretary) and the Department of Defence (Senior Assistant Secretary), and retired from the public service in 1975. He holds a Bachelor of Commerce degree (Melbourne University) and was a graduate of the Australian Staff College, ‘Manyung’, Mt Eliza, Victoria. He has been a volunteer at the Australian War Memorial for 21 years doing research into aircraft relics held at the AWM, and more recently research work into RAAF World War 2 fatalities. He has written and published eight books on RAAF fatalities in the eight RAAF Squadrons serving in RAF Bomber Command in WW2.