List of Written Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FLW January 2010

Family Law Week August 2011 - 1 August 2011 News 1 mediation and representation. Analysis NEWS Cases which can have outcomes which the Government defines as Leave to Remove and the 20 Baroness Hale attacks serious, such as homelessness, Payne Discipline – Breaking the Impasse government's legal aid domestic violence, loss of liberty, proposals discrimination, human rights Leave to Remove – 25 issues and abuse of power by the Improving Due Process Baroness Hale of Richmond has criticised state, will remain in scope; while The End of Payne? 31 the government's proposals to cut legal other kinds of housing case, debts, 34 aid. Lady Hale was delivering the 2011 welfare benefits, employment, Finance & Divorce Update Summer 2011 Sir Henry Hodge Memorial Lecture at immigration, education, and most the Law Society entitled 'Equal Access to family breakdown will come out. Cost Orders in Public Law 39 Justice in the Big Society'. But mediation in family disputes Proceedings: A New stays in.' Approach? Referring to the Legal Aid, Sentencing Children: Public Law Update 42 and Punishment of Offenders Bill, which However, she commented: (July 2011) passed its second reading in the House of Commons on the 29th June, Lady Hale 'In real life, as we all know and Cases said that the government's own equality research has shown, clients come with a variety of interlocking A County Council v K & Ors 44 impact statement accepts that the cuts (By the Child's Guardian HT) will have a disproportionate impact problems. Family breakdown can [2011] EWHC 1672 (Fam) upon women, ethnic minorities and easily lead people into debt, if K (Children) [2011] EWCA people with disabilities. -

Judges and Judicial Independence

GILLES_Ch06.qxd 1/12/07 6:41 PM Page 173 6 Judges and Judicial Independence By the end of this chapter you will be able to: • Identify the key judicial offices, their ranks and styles. • Understand how judges are appointed and assess the recent changes. • Discuss the merits of the current judicial structure. • Assess the independence of the judiciary. GILLES_Ch06.qxd 1/12/07 6:41 PM Page 174 174 6 JUDGES AND JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE Introduction At the heart of the English Legal System is the judiciary, a body of persons often caricatured in the media as doddery old men who are bordering on being senile. The truth, however, is that both the full-time and part-time judiciary in England and Wales are extremely professional persons who have come from the very best of the Bar and solicitors. That is not to say that controversy does not surround the judiciary and, in particular, the way that they operate and are appointed to their office. Scepticism also exists as to the role the state has in the execution of the judicial office, ie is there such a thing as judicial independence? In this chapter these issues will be discussed. As will be seen, there are different types of judges within the English Legal System and these differences are echoed in how they are styled and referred to. The Law Reports, and many other legal publications, will use abbreviations to refer to judges. The following table helpfully summarizes how the different grade of judges are styled, abbreviated and referred to in court. -

Final Zero Checked 2

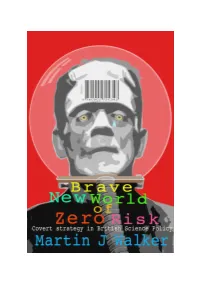

Brave New World of Zero Risk: Covert Strategy in British Science Policy Martin J Walker Slingshot Publications October 2005 Brave New World of Zero Risk: Covert Strategy in British Science Policy Martin J. Walker First published as an e-book, October 2005 © Slingshot Publications, October 2005 BM Box 8314, London WC1N 3XX, England Type set by Viviana D. Guinarte in Book Antiqua 11/12, Verdana Edited by Rose Shepherd Cover design by Andy Dark In this downloadable Pdf form this book is free and can be distributed by anyone as long as neither the contents or the cover are changed or altered in any way and that this condition is imposed upon anyone who further receives or distributes the book. In the event of anyone wanting to print hard copies for distribution, rather than personal use, they should consult the author through Slingshot Publications. Selected parts of the book can be reproduced in any form, except that of articles under the author’s name, for which he would in other circumstances receive payment; again these can be negotiated through Slingshot Publications. More information about this book can be obtained at: www.zero-risk.org For Marxists and neo liberals alike it is technological advance that fuels economic development, and economic forces that shape society. Politics and culture are secondary phenomena, sometimes capable of retarding human progress; but in the last analysis they cannot prevail against advancing technology and growing productivity. John Gray1 The Bush government is certainly not the first to abuse science, but they have raised the stakes and injected ideology like no previous administration. -

Increasing Judicial Diversity

Increasing judicial diversity A Report by JUSTICE Chair of the Working Party Nathalie Lieven QC Established in 1957 by a group of leading jurists, JUSTICE is an all-party law reform and human rights organisation working to strengthen the justice system – administrative, civil and criminal – in the United Kingdom. We are a membership organisation, composed largely of legal professionals, ranging from law students to the senior judiciary. Our vision is of fair, accessible and efficient legal processes, in which the individual’s rights are protected, and which reflect the country’s international reputation for upholding and promoting the rule of law. To this end: yyWe carry out research and analysis to generate, develop and evaluate ideas for law reform, drawing on the experience and insights of our members. yyWe intervene in superior domestic and international courts, sharing our legal research, analysis and arguments to promote strong and effective judgments. yyWe promote a better understanding of the fair administration of justice among political decision-makers and public servants. yyWe bring people together to discuss critical issues relating to the justice system, and to provide a thoughtful legal framework to inform policy debate. © JUSTICE April 2017 59 Carter Lane, London EC4V 5AQ www.justice.org.uk THE WORKING PARTY Nathalie Lieven QC (Chair) Diane Burleigh OBE Kate Cheetham Andrea Coomber Stephen Frost Sa’ad Hossain QC Professor Rosemary Hunter Sir John Goldring Sir Paul Jenkins Rachel Jones (Rapporteur) George Lubega Ruchi Parekh Geoffrey Robertson QC Karamjit Singh CBE Tim Smith MEMBERS OF SUB GROUPS Rachel Barrett Carlos Dabezies Simon Davis Christina Liciaga Caroline Sheppard Emma Slatter David Wurtzel Please note that the views expressed in this report are those of the Working Party members alone, and do not reflect the views of the organisations or institutions to which they belong. -

The Ghost Lobby and Other Mysteries of the Modern Physic

MARTIN J. WALKER MA 7KH*KRVW/REE\DQG 2WKHU0\VWHULHVRIWKH0RGHUQ3K\VLF Wyeth Pharmaceuticals and New Labour 7RVZLQGOHRWKHUSHRSOHZDVDIWHUDOOWKHKRQHVWDLPRIHYHU\EXVLQHVVPDQ 2QO\WKHZRUOGZDVDOZD\VVRPXFKZLFNHGHUWKDQRQHWKRXJKW 7KHUHVHHPHGWREHQROLPLWWRHYLO Bertolt Brecht1. $VDQDLOVWLFNHWKEHWZHHQWKHMRLQLQJVRIWKHVWRQHV VRGRWKVLQVWLFNFORVHWREX\LQJDQGVHOOLQJ Ecclesiastes 1HZODERXUKDGRSHQHGXSVHFUHWURXWHVRIVSHFLDO DFFHVVWRDOORZVHOHFWFRUSRUDWHFKLHIVWR EDUJDLQDOWHURUYHWRWKHJRYHUQPHQW¶VNH\GHFLVLRQV Greg Palast2 6ince coming to power in 1997, New Labour has been ‘modernizing’ the National Health Service (NHS). Essentially this modernization process has entailed placing the management of health care delivery, in its many different forms, in the hands of free standing agencies; private companies, trusts, foundations, consultancies and even pharmacists3. The changes introduced by this decentralization have broken the mould of a system of socialized medicine, inaugurated by the first Labour Government over half a century 1 Threepenny Novel. Penguin Books. Harmondsworth, England. 1973. 2 Lobbygate, Chapter 7, in The Best Democracy Money Can Buy, Greg Palast, Robinson, London2003 3 In May 2004, the New Labour government became the first European government to move statins (cholesterol lowering drugs), from the prescription list to over the counter sales, also allowing competitive advertising within the pharmacists. This move will wipe millions off the prescription drugs bill, forcing patients to pay from their own pockets for treatment. At the same time, it is a gift to the pharmaceutical industry, which is straining at the leash to by-pass doctors and all kinds of patient–protecting legislation and sell drugs directly to the general population. Who will the consumer sue when they suffer serious adverse reactions, the chemist? To whom does the patient report adverse reactions? Planning to bring pharmacists more deeply into the NHS and make them, as it were, auxillary doctors, began four years ago. -

Senior President of Tribunals Third Implementation Review

SENIOR PRESIDENT OF TRIBUNALS THIRD IMPLEMENTATION REVIEW INTRODUCTION 1. My First and Second Implementation Reviews were published respectively in June and October 2008. They described the steps leading to the first stage of implementation of the Part I of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, including the governance structure of the new systems and its relationship with other bodies. That took place on the 3rd November 2008, with the establishment of the Upper Tribunal and the First-tier Tribunal. The Upper Tribunal began with a single chamber: the Administrative Appeals Chamber. The First-tier Tribunal had three chambers: Social Entitlement; Health, Education and Social Care; and War Pensions and Armed Forces Compensation. I am grateful to all concerned that the transfer took place with minimal disruption to ordinary business. 2. The first two Reviews are available on the Tribunals Service website at http://www.tribunals.gov.uk/Tribunals/Publications/publications.htm. The purpose of the present Third Review is to bring the story up to date, to highlight any significant changes from the arrangements set out in the previous review, and to outline the next few months. In the Autumn I intend to publish my first Annual Report, which will complete the account of the first year and meet the statutory requirements for reporting under section 43 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007. 3. Since November, there have been two significant further additions to the new system: tax and lands. The next steps include the establishment of the General Regulatory Chamber in the First-tier, and the transfer of the jurisdictions of the Asylum and Immigration Tribunal. -

Child Poverty Action Group 1965-2015

THE CHILD POVERTY ACTION GROUP 1965 TO 2015 Pat Thane and Ruth Davidson THE CHILD POVERTY ACTION GROUP 1965 TO 2015 Pat Thane and Ruth Davidson MAY 2016 Child Poverty Action Group works on behalf of the one in four children in the UK growing up in poverty. It does not have to be like this: we work to understand what causes poverty, the impact it has on children’s lives, and how it can be prevented and solved – for good. We develop and campaign for policy solutions to end child poverty. We also provide accurate information, training and advice to the people who work with hard-up families, to make sure they get the financial support they need, and carry out high profile legal work to establish and confirm families’ rights. If you are not already supporting us, please consider making a donation, or ask for details of our membership schemes, training courses and publications. Published by CPAG 30 Micawber Street, London N1 7TB Tel: 020 7837 7979 staff@cpag.org.uk www.cpag.org.uk © Child Poverty Action Group 2016 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. Child Poverty Action Group is a charity registered in England and Wales (registration number 294841) and in Scotland (registration number SC039339), and is a company limited by guarantee, registered in England (registration number 1993854). -

The Great and Good?

Centre for Policy Studies THE GREAT AND GOOD? THE RISE OF THE NEW CLASS Martin McElwee THE AUTHOR Martin McElwee was educated at Trinity High Comprehensive School, Glasgow and at Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge (where he attained first-class degrees in Law at undergraduate and masters levels). He is currently Deputy Editor at the Centre for Policy Studies. The Centre for Policy Studies never expresses a corporate view in any of its publications. Contributions are chosen for their independence of thought and cogency of argument. Centre for Policy Studies, 2000 ISBN No: 1 903219 03 5 Centre for Policy Studies 57 Tufton Street, London SW1P 3QL Tel: 0171 222 4488 Fax: 0171 222 4388 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.cps.org.uk Printed by The Chameleon Press, 5 – 25 Burr Road, London SW18 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE CONCEPT OF THE NEW CLASS 1 THE CREATION OF THE NEW CLASS 6 THE MEDIA AND THE NEW CLASS 22 BUSINESS AND THE NEW CLASS 28 SHOWBUSINESS, CULTURE & THE ARTS AND THE NEW CLASS 34 LAWYERS AND THE NEW CLASS 40 ACADEMICS AND THE NEW CLASS 42 FRIENDS AND DONORS 45 APPENDIX 1: KEY FIGURES IN THE NEW CLASS APPENDIX 2: BIOGRAPHIES OF THE SPECIAL ADVISERS INTRODUCTION THE CONCEPT OF THE NEW CLASS The Prime Minister has a vision of a New Britain. Central to this vision is the creation of a “New Class”, a new elite placed in positions of authority, who will propagate the new spirit of the age and spread the principles of the Third Way across Britain. -

Balliol College Annual Record 2009

Balliol College Annual Record 2009 The College was founded by John Balliol of Barnard Castle in the county of Durham and Dervorguilla his wife (parents of John Balliol, King of Scotland), some time before June 1266, traditionally in 1263. Editor Denis Noble Assistant Editor Jacqueline Smith H Balliol College Oxford OX1 3BJ Telephone: (01865) 277777 Fax: (01865) 277803 Website: www.balliol.ox.ac.uk Printed by Oxuniprint Oxford University Press front cover: Coverage of a protest at the Clarendon building against the Proctors’ leafleting ban, Daily Telegraph, 4 June 1968. Contents Visitor, Master, Fellows and Lecturers, Preachers in Chapel 1 The Master’s Letter 7 Balliol’s Revolution 1968–1975 Denis Noble Introduction: the view from Holywell 11 Neil MacCormick 1968 and all that 13 Alan Montefiore Memories of turbulence 16 Martin Kettle It was right to rebel 19 Richard Jenkyns The revolution that wasn’t 22 Stephen Bergman The Balliol revolution: an American view 25 Jon Moynihan The events of ’68: a social, not a political, phenomenon 30 Philip McDonagh Justifying Jowett: an Irishman at Balliol, 1970–1974 36 Penelope J. Corfield Christopher Hill: Marxist history and Balliol College 39 Balliol graffiti 42 Obituaries: Sir Neil MacCormick 43 Vernon Handley 45 Tuanku Abdul Rahman 48 Bernie Brooks 49 Book Reviews: Ian Goldin: The Bridge at the End of the World, by James Gustave Speth 51 Paul Slack: The Ends of Life, by Keith Thomas 52 Ben Morison: From Empedocles to Wittgenstein, by Anthony Kenny 53 Hagan Bayley: The Dyson Perrins Laboratory and