JOHN LEWIS 2012.3.113 Recording Opens with Unidentified Speaker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF Mourns the Loss of the Honora

LDF Mourns the Loss of Congressman John Lewis, Legendary and Beloved Civil Rights Icon Today, LDF mourns the loss of The Honorable John Lewis, an esteemed member of Congress and revered civil rights icon with whom our organization has a deeply personal history. Mr. Lewis passed away on July 17, 2020, following a battle with pancreatic cancer. He was 80 years old. “I don’t know of another leader in this country with the moral standing of Rep. John Lewis. His life and work helped shape the best of our national identity,” said Sherrilyn Ifill, LDF’s President & Director-Counsel. “We revered him not only for his work and sacrifices during the Civil Rights Movement, but because of his unending, stubborn, brilliant determination to press for justice and equality in this country. “There was no cynicism in John Lewis; no hint of despair even in the darkest moments. Instead, he showed up relentlessly with commitment and determination - but also love, and joy and unwavering dedication to the principles of non-violence. He spoke up and sat-in and stood on the front lines – and risked it all. This country – every single person in this country – owes a debt of gratitude to John Lewis that we can only begin to repay by following his demand that we do more as citizens. That we ‘get in the way.’ That we ‘speak out when we see injustice’ and that we keep our ‘eyes on the prize.’” The son of sharecroppers, Mr. Lewis was born on Feb. 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama. He grew up attending segregated public schools in the state’s Pike County and, as a boy, was inspired by the work of civil rights activists, including Dr. -

What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective During the Civil Rights Movement?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 5011th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? © Bettmann / © Corbis/AP Images. Supporting Questions 1. What was tHe impact of the Greensboro sit-in protest? 2. What made tHe Montgomery Bus Boycott, BirmingHam campaign, and Selma to Montgomery marcHes effective? 3. How did others use nonviolence effectively during the civil rights movement? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 11th Grade Civil Rights Inquiry What Made Nonviolent Protest Effective during the Civil Rights Movement? 11.10 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGE/DOMESTIC ISSUES (1945 – PRESENT): Racial, gender, and New York State socioeconomic inequalities were addressed By individuals, groups, and organizations. Varying political Social Studies philosophies prompted debates over the role of federal government in regulating the economy and providing Framework Key a social safety net. Idea & Practices Gathering, Using, and Interpreting Evidence Chronological Reasoning and Causation Staging the Discuss tHe recent die-in protests and tHe extent to wHicH tHey are an effective form of nonviolent direct- Question action protest. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 Supporting Question 3 Guided Student Research Independent Student Research What was tHe impact of tHe What made tHe Montgomery Bus How did otHers use nonviolence GreensBoro sit-in protest? boycott, the Birmingham campaign, effectively during tHe civil rights and tHe Selma to Montgomery movement? marcHes effective? Formative Formative Formative Performance Task Performance Task Performance Task Create a cause-and-effect diagram tHat Detail tHe impacts of a range of actors Research the impact of a range of demonstrates the impact of the sit-in and tHe actions tHey took to make tHe actors and tHe effective nonviolent protest by the Greensboro Four. -

Viewer's Guide

SELMA T H E BRIDGE T O T H E BALLOT TEACHING TOLERANCE A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER VIEWER’S GUIDE GRADES 6-12 Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is the story of a courageous group of Alabama students and teachers who, along with other activists, fought a nonviolent battle to win voting rights for African Americans in the South. Standing in their way: a century of Jim Crow, a resistant and segregationist state, and a federal govern- ment slow to fully embrace equality. By organizing and marching bravely in the face of intimidation, violence, arrest and even murder, these change-makers achieved one of the most significant victories of the civil rights era. The 40-minute film is recommended for students in grades 6 to 12. The Viewer’s Guide supports classroom viewing of Selma with background information, discussion questions and lessons. In Do Something!, a culminating activity, students are encouraged to get involved locally to promote voting and voter registration. For more information and updates, visit tolerance.org/selma-bridge-to-ballot. Send feedback and ideas to [email protected]. Contents How to Use This Guide 4 Part One About the Film and the Selma-to-Montgomery March 6 Part Two Preparing to Teach with Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot 16 Part Three Before Viewing 18 Part Four During Viewing 22 Part Five After Viewing 32 Part Six Do Something! 37 Part Seven Additional Resources 41 Part Eight Answer Keys 45 Acknowledgements 57 teaching tolerance tolerance.org How to Use This Guide Selma: The Bridge to the Ballot is a versatile film that can be used in a variety of courses to spark conversations about civil rights, activism, the proper use of government power and the role of the citizen. -

IN HONOR of FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW from ROSA PARKS to the TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 67 Issue 4 Article 10 2017 SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction Jonathan L. Entin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan L. Entin, SYMPOSIUM: IN HONOR OF FRED GRAY: MAKING CIVIL RIGHTS LAW FROM ROSA PARKS TO THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY - Introduction, 67 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1025 (2017) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol67/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 67·Issue 4·2017 —Symposium— In Honor of Fred Gray: Making Civil Rights Law from Rosa Parks to the Twenty-First Century Introduction Jonathan L. Entin† Contents I. Background................................................................................ 1026 II. Supreme Court Cases ............................................................... 1027 A. The Montgomery Bus Boycott: Gayle v. Browder .......................... 1027 B. Freedom of Association: NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Patterson ....... 1028 C. Racial Gerrymandering: Gomillion v. Lightfoot ............................. 1029 D. Constitutionalizing the Law of -

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement

Women in the Modern Civil Rights Movement Introduction Research Questions Who comes to mind when considering the Modern Civil Rights Movement (MCRM) during 1954 - 1965? Is it one of the big three personalities: Martin Luther to Consider King Jr., Malcolm X, or Rosa Parks? Or perhaps it is John Lewis, Stokely Who were some of the women Carmichael, James Baldwin, Thurgood Marshall, Ralph Abernathy, or Medgar leaders of the Modern Civil Evers. What about the names of Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Rights Movement in your local town, city or state? Nash, Daisy Bates, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ruby Bridges, or Claudette Colvin? What makes the two groups different? Why might the first group be more familiar than What were the expected gender the latter? A brief look at one of the most visible events during the MCRM, the roles in 1950s - 1960s America? March on Washington, can help shed light on this question. Did these roles vary in different racial and ethnic communities? How would these gender roles On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 men, women, and children of various classes, effect the MCRM? ethnicities, backgrounds, and religions beliefs journeyed to Washington D.C. to march for civil rights. The goals of the March included a push for a Who were the "Big Six" of the comprehensive civil rights bill, ending segregation in public schools, protecting MCRM? What were their voting rights, and protecting employment discrimination. The March produced one individual views toward women of the most iconic speeches of the MCRM, Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a in the movement? Dream" speech, and helped paved the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and How were the ideas of gender the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

From Stride Toward Freedom Necessary to Protect Ourselves

Civil Rights and Protest Literature from Stride Toward Freedom RI 2 Determine two or more Nonfiction by Martin Luther King Jr. central ideas of a text and analyze their development over For a biography of Martin Luther King Jr., see page 1202. the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to provide a Necessary to Protect Ourselves complex analysis. RI 5 Analyze Interview with Malcolm X by Les Crane and evaluate the effectiveness of the structure an author uses in his or her argument, including whether the structure makes Meet the Author points clear, convincing, and engaging. RI 6 Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in a text in which the rhetoric is Malcolm X 1925–1965 particularly effective, analyzing how style and content contribute In 1944, while Martin Luther King Jr. people “a race of devils” and promoted a to the power, persuasiveness, or beauty of the text. was attending college classes in Atlanta, vision of black pride. They advocated a 19-year-old Malcolm Little was hustling on radical solution to the race problem: the the streets of Harlem. By 1952, a jailhouse establishment of a separate, self-reliant conversion transformed Little into the black nation. political firebrand we know as Malcolm Change of Heart Inspired by the Black X, whose separatist views posed a serious Muslim vision, Malcolm Little converted challenge to King’s integrationist vision. to Islam and changed his last name to Bitter Legacy Where King grew up X, symbolizing his lost African name. comfortably middle-class, Little’s childhood Once released from prison, he became an was scarred by poverty and racial violence. -

Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information

“The Top Ten” Leaders of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom Biographical Information (Asa) Philip Randolph • Director of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. • He was born on April 15, 1889 in Crescent City, Florida. He was 74 years old at the time of the March. • As a young boy, he would recite sermons, imitating his father who was a minister. He was the valedictorian, the student with the highest rank, who spoke at his high school graduation. • He grew up during a time of intense violence and injustice against African Americans. • As a young man, he organized workers so that they could be treated more fairly, receiving better wages and better working conditions. He believed that black and white working people should join together to fight for better jobs and pay. • With his friend, Chandler Owen, he created The Messenger, a magazine for the black community. The articles expressed strong opinions, such as African Americans should not go to war if they have to be segregated in the military. • Randolph was asked to organize black workers for the Pullman Company, a railway company. He became head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first black labor union. Labor unions are organizations that fight for workers’ rights. Sleeping car porters were people who served food on trains, prepared beds, and attended train passengers. • He planned a large demonstration in 1941 that would bring 10,000 African Americans to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC to try to get better jobs and pay. The plan convinced President Roosevelt to take action. -

<Billno> <Sponsor>

<BillNo> <Sponsor> HOUSE JOINT RESOLUTION 8020 of the Second Extraordinary Session By Clemmons A RESOLUTION to honor the memory of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis. WHEREAS, the members of this General Assembly were greatly saddened to learn of the passing of United States Congressman John Robert Lewis; and WHEREAS, Congressman John Lewis dedicated his life to protecting human rights, securing civil liberties, and building what he called "The Beloved Community" in America; and WHEREAS, referred to as "one of the most courageous persons the Civil Rights Movement ever produced," Congressman Lewis evidenced dedication and commitment to the highest ethical standards and moral principles and earned the respect of his colleagues on both sides of the aisle in the United States Congress; and WHEREAS, John Lewis, the son of sharecropper parents Eddie and Willie Mae Carter Lewis, was born on February 21, 1940, outside of Troy, Alabama, and was raised on his family's farm with nine siblings; and WHEREAS, he attended segregated public schools in Pike County, Alabama, and, in 1957, became the first member of his family to complete high school; he was vexed by the unfairness of racial segregation and disappointed that the Supreme Court's 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education did not affect his and his classmates' experience in public school; and WHEREAS, Congressman Lewis was inspired to work toward the change he wanted to see by Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s sermons and the outcome of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and -

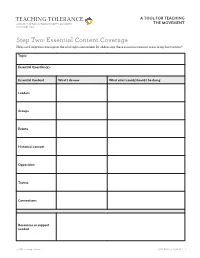

Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How Can I Improve Coverage of the Civil Rights Movement by Addressing These Essential Content Areas in My Instruction?

TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: Essential Question(s): Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should I be doing Leaders Groups Events Historical context Opposition Tactics Connections Resources or support needed © 2014 Teaching Tolerance CIVIL RIGHTS DONE RIGHT TEACHING TOLERANCE A TOOL FOR TEACHING A PROJECT OF THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER THE MOVEMENT TOLERANCE.ORG Step Two: Essential Content Coverage (SAMPLE) How can I improve coverage of the civil rights movement by addressing these essential content areas in my instruction? Topic: 1963 March on Washington Essential Question(s): How do the events and speeches of the 1963 March on Washington illustrate the characteristics of the civil rights movement as a whole? Essential Content What I do now What else I could/should be doing Leaders Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, John Lewis, Roy A. Philip Randolph Wilkins, Whitney Young, Dorothy Height Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), Student Nonviolent Groups Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), National Urban League (NUL), Negro American Labor Council (NALC) The 1963 March on Washington was one of the most visible and influential Some 250,000 people were present for the March Events events of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther on Washington. They marched from the Washington King Jr. -

Confessions of a Dangerous Mind

CONFESSIONS OF A DANGEROUS MIND a screenplay by Charlie Kaufman based on CONFESSIONS OF A DANGEROUS MIND an unauthorized biography by Chuck Barris third draft (revised) May 5, 1998 MUSIC IN: OMINOUS ORCHESTRAL TEXT, WHITE ON BLACK: This film is a reenactment of actual events. It is based on Mr. Barris's private journals, public records, and hundreds of hours of taped interviews. FADE IN: EXT. NYC STREET - NIGHT SUBTITLE: NEW YORK CITY, FALL 1981 It's raining. A cab speeds down a dark, bumpy side-street. INT. CAB - CONTINUOUS Looking in his rearview mirror, the cab driver checks out his passenger: a sweaty young man in a gold blazer with a "P" insignia over his breast pocket. Several paper bags on the back seat hedge him in. The young man is immersed in the scrawled list he clutches in his hand. A passing street light momentarily illuminates the list and we glimpse a few of the entries: double-coated waterproof fuse (500 feet); .38 ammo (hollowpoint configuration); potato chips (Lays). GONG SHOW An excerpt from The Gong Show (reenacted). The video image fills the screen. We watch a fat man recite Hamlet, punctuating his soliloquy with loud belching noises. The audience is booing. Eventually the man gets gonged. Chuck Barris, age 50, hat pulled over his eyes, dances out from the wings to comfort the agitated performer. PERFORMER Why'd they do that? I wasn't done. BARRIS (AGE 50) I don't understand. Juice, why'd you gong this nice man? JAYE P. MORGAN Not to be. That is the answer. -

African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship

Catholic University Law Review Volume 43 Issue 1 Fall 1993 Article 4 1993 Ironic Encounter: African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship Dena S. Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Dena S. Davis, Ironic Encounter: African-Americans, American Jews, and the Church-State Relationship, 43 Cath. U. L. Rev. 109 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.edu/lawreview/vol43/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Catholic University Law Review by an authorized editor of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IRONIC ENCOUNTER: AFRICAN-AMERICANS, AMERICAN JEWS, AND THE CHURCH- STATE RELATIONSHIP Dena S. Davis* I. INTRODUCTION This Essay examines a paradox in contemporary American society. Jewish voters are overwhelmingly liberal and much more likely than non- Jewish white voters to support an African-American candidate., Jewish voters also staunchly support the greatest possible separation of church * Assistant Professor, Cleveland-Marshall College of Law. For critical readings of earlier drafts of this Essay, the author is indebted to Erwin Chemerinsky, Stephen W. Gard, Roger D. Hatch, Stephan Landsman, and Peter Paris. For assistance with resources, the author obtained invaluable help from Michelle Ainish at the Blaustein Library of the American Jewish Committee, Joyce Baugh, Steven Cohen, Roger D. Hatch, and especially her research assistant, Christopher Janezic. This work was supported by a grant from the Cleveland-Marshall Fund. 1. In the 1982 California gubernatorial election, Jewish voters gave the African- American candidate, Tom Bradley, 75% of their vote; Jews were second only to African- Americans in their support for Bradley, exceeding even Hispanics, while the majority of the white vote went for the white Republican candidate, George Deukmejian. -

An Established Leader in Legal Education Robert R

An Established Leader In Legal Education Robert R. Bond, First Graduate, Class of 1943 “Although N. C. Central University School of Law has had to struggle through some difficult periods in its seventy-year history, the School of Law has emerged as a significant contributor to legal education and the legal profession in North Carolina.” Sarah Parker Chief Justice North Carolina State Supreme Court “Central’s success is a tribute to its dedicated faculty and to its graduates who have become influential practitioners, successful politicians and respected members of the judiciary in North Carolina.” Irvin W. Hankins III Past President North Carolina State Bar The NCCU School of Law would like to thank Michael Williford ‘83 and Harry C. Brown Sr. ‘76 for making this publication possible. - Joyvan Malbon '09 - Professor James P. Beckwith, Jr. North Carolina Central University SCHOOL OF LAW OUR MISSION The mission of the North Carolina Central University School of Law is to provide a challenging and broad-based educational program designed to stimulate intellectual inquiry of the highest order, and to foster in each student a deep sense of professional responsibility and personal integrity so as to produce competent and socially responsible members of the legal profession. 2 NCCU SCHOOL OF LAW: SO FAR th 70 Anniversary TABLE OF CONTENTS 70TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION 4 PORTRAITS OF THE DEANS 2009 NORTH CAROLINA CENTRAL UNIVERSITY 6 ROBERT BOND ‘43: The Genesis of North Carolina SCHOOL OF LAW Central University’s School of Law DEAN: 8 THE STARTING POINT RAYMOND C. PIERCE EDITOR: 12 THE EARLY YEARS MARCIA R.