Listening Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bath Festival Orchestra Programme 2021

Bath Festival Orchestra photo credit: Nick Spratling Peter Manning Conductor Rowan Pierce Soprano Monday 17 May 7:30pm Bath Abbey Programme Carl Maria von Weber Overture: Der Freischütz Weber Der Freischütz (Op.77, The Marksman) is a German Overture to Der Freischütz opera in three acts which premiered in 1821 at the Schauspielhaus, Berlin. Many have suggested that it was the first important German Romantic opera, Strauss with the plot based around August Apel’s tale of the same name. Upon its premiere, the opera quickly 5 Orchestral Songs became an international success, with the work translated and rearranged by Hector Berlioz for a French audience. In creating Der Freischütz Weber Brentano Lieder Op.68 embodied the ideal of the Romantic artist, inspired Ich wollt ein Sträuẞlein binden by poetry, history, folklore and myths to create a national opera that would reflect the uniqueness of Säusle, liebe Myrthe German culture. Amor Weber is considered, alongside Beethoven, one of the true founders of the Romantic Movement in Morgen! Op.27 music. He lived a creative life and worked as both a pianist and music critic before making significant contributions to the operatic genre from his appointment at the Dresden Staatskapelle in 1817, Das Rosenband Op.36 where he realised that the opera-goers were hearing almost nothing other than Italian works. His three German operas acted as a remedy to this situation, Brahms with Weber hoping to embody the youthful Serenade No.1 in D, Op.11 Romantic movement of Germany on the operatic stage. These works not only established Weber as a long-lasting Romantic composer, but served to define German Romanticism and make its name as an important musical force in Europe throughout the 19th century. -

Mahler's Song of the Earth

SEASON 2020-2021 Mahler’s Song of the Earth May 27, 2021 Jessica GriffinJessica SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Thursday, May 27, at 8:00 On the Digital Stage Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Michelle DeYoung Mezzo-soprano Russell Thomas Tenor Mahler/arr. Schoenberg and Riehn Das Lied von der Erde I. Das Trinklied von Jammer der Erde II. Der Einsame im Herbst III. Von der Jugend IV. Von der Schönheit V. Der Trunkene im Frühling VI. Der Abschied First Philadelphia Orchestra performance of this version This program runs approximately 1 hour and will be performed without an intermission. This concert is part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. Our World Lead support for the Digital Stage is provided by: Claudia and Richard Balderston Elaine W. Camarda and A. Morris Williams, Jr. The CHG Charitable Trust Innisfree Foundation Gretchen and M. Roy Jackson Neal W. Krouse John H. McFadden and Lisa D. Kabnick The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Leslie A. Miller and Richard B. Worley Ralph W. Muller and Beth B. Johnston Neubauer Family Foundation William Penn Foundation Peter and Mari Shaw Dr. and Mrs. Joseph B. Townsend Waterman Trust Constance and Sankey Williams Wyncote Foundation SEASON 2020-2021 The Philadelphia Orchestra Yannick Nézet-Séguin Music Director Walter and Leonore Annenberg Chair Nathalie Stutzmann Principal Guest Conductor Designate Gabriela Lena Frank Composer-in-Residence Erina Yashima Assistant Conductor Lina Gonzalez-Granados Conducting Fellow Frederick R. -

Kodály and Orff: a Comparison of Two Approaches in Early Music Education

ZKÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, Cilt 8, Sayı 15, 2012 ZKU Journal of Social Sciences, Volume 8, Number 15, 2012 KODÁLY AND ORFF: A COMPARISON OF TWO APPROACHES IN EARLY MUSIC EDUCATION Yrd.Doç.Dr. Dilek GÖKTÜRK CARY Karabük Üniversitesi Safranbolu Fethi Toker Güzel Sanatlar ve Tasarım Fakültesi Müzik Bölümü [email protected] ABSTRACT The Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) and the German composer Carl Orff (1895-1982) are considered two of the most influential personalities in the arena of music education during the twentieth-century due to two distinct teaching methods that they developed under their own names. Kodály developed a hand-sign method (movable Do) for children to sing and sight-read while Orff’s goal was to help creativity of children through the use of percussive instruments. Although both composers focused on young children’s musical training the main difference between them is that Kodály focused on vocal/choral training with the use of hand signs while Orff’s main approach was mainly on movement, speech and making music through playing (particularly percussive) instruments. Finally, musical creativity via improvisation is the main goal in the Orff Method; yet, Kodály’s focal point was to dictate written music. Key Words: Zoltán Kodály, Carl Orff, The Kodály Method, The Orff Method. KODÁLY VE ORFF: ERKEN MÜZİK EĞİTİMİNDE KULLANILAN İKİ METODUN BİR KARŞILAŞTIRMASI ÖZET Macar besteci ve etnomüzikolog Zoltán Kodály (1882-1967) ve Alman besteci Carl Orff (1895-1982) geliştirmiş oldukları farklı 2 öğretim metodundan dolayı 20. yüzyılda müzik eğitimi alanında en etkili 2 kişi olarak anılmaktadırlar. Kodály çocukların şarkı söyleyebilmeleri ve deşifre yapabilmeleri için el işaretleri metodu (gezici Do) geliştirmiş, Orff ise vurmalı çalgıların kullanımı ile çocukların yaratıcılıklarını geliştirmeyi hedef edinmiştir. -

Two Analytical Essays

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2020 Two Analytical Essays Abigail Rueger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.256 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rueger, Abigail, "Two Analytical Essays" (2020). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 162. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/162 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

Chamberfest 2018

ChamberFest 2018 elcome to the 17th annual Juilliard ChamberFest. This year 140 students and faculty return one W week early from the winter recess for a tuition-free chamber music intensive. Working without interruption in the nearly empty Juilliard building in great depth on repertoire they have selected themselves, the musicians have found that ChamberFest’s unlimited rehearsal time and daily coaching yields an extraordinarily rich artistic and educational result. This experience therefore not only nurtures the devoted chamber musician at Juilliard, it also nurtures the broad and reflective education necessary for the training of the 21st-century artist-citizen. Launched in 2002, ChamberFest occupies a unique place in the life of the school, and after this year will have presented 1,300 students in 270 ensemble pairings with Juilliard faculty and guest coaches for almost 300 performances. Juilliard’s musicians have been joined in the past by students from London’s Royal Academy of Music, France’s Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris, Vienna’s Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien, and the orchestra academy of Brazil’s São Paulo State Symphony Orchestra. Past guest coaches have included soprano Barbara Hannigan, MacArthur Fellow Liz Lerman, and pianist Peter Serkin. ChamberFest has been a home for the traditional—works by Beethoven, Brahms, Dvorˇák, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Schubert and Shostakovich top the list—and the unusual. Included among the latter are interdisciplinary chamber music performances with dancers and choreographers; improvised presentations; premieres; the inclusion of distinctive European instruments rarely heard in the U.S. including the Vienna clarinet, Vienna pumphorn and the French bassoon; and this year’s season opener, by Claudio Papapietro Photo of cellist Khari Joyner Photo by Claudio Papapietro John Corigliano’s evocative Chiaroscuro for two pianos—with one piano tuned a quarter-tone lower than the other. -

Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen Abendlied Easy Piano Sheet Music

Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen Abendlied Easy Piano Sheet Music Download der mond ist aufgegangen abendlied easy piano sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 1 pages partial preview of der mond ist aufgegangen abendlied easy piano sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 3796 times and last read at 2021-09-25 20:15:45. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of der mond ist aufgegangen abendlied easy piano you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Easy Piano, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Beginning [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen Abendlied Evening Song Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen Abendlied Evening Song sheet music has been read 3752 times. Der mond ist aufgegangen abendlied evening song arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-25 20:24:20. [ Read More ] The Moon Is Risen Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen The Moon Is Risen Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen sheet music has been read 3015 times. The moon is risen der mond ist aufgegangen arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 2 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 08:57:38. [ Read More ] Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen German Folk Song Clarinet Quartet Der Mond Ist Aufgegangen German Folk Song Clarinet Quartet sheet music has been read 3829 times. Der mond ist aufgegangen german folk song clarinet quartet arrangement is for Intermediate level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-24 20:49:30. -

Symphony Band Chamber Winds Michael Haithcock, Conductor

SYMPHONY BAND CHAMBER WINDS MICHAEL HAITHCOCK, CONDUCTOR NICHOLAS BALLA, KIMBERLY FLEMING & JOANN WIESZCZYK, GRADUATE STUDENT CONDUCTORS Friday, February 12, 2021 Hill Auditorium 8:00 PM Il barbiere di Siviglia: Overture (1816) Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868) arr. Wenzel Sedlak JoAnn Wieszczyk, conductor Three Dances and Final Scene from Der Mond (1939) Carl Orff Dance 1 (1895–1982) Dance 2 arr. Friedrich K. Wanek Final Scene Dance 3 JoAnn Wieszczyk, conductor Selene (Moon Chariot Rituals) (2015) Augusta Reed Thomas (b. 1964) arr. Cliff Colnot Intermission Timbuktuba (1995) Michael Daugherty (b. 1954) Nicholas Balla, conductor Bull’s-Eye (2019) Viet Cuong (b. 1990) Kimberly Fleming, conductor Symphony for Brass and Timpani (1956) Herbert Haufrecht Dona Nobis Pacem (1909–1998) Elegy Jubilation THe use of all cameras and recording devices is strictly prohibited. Please turn off all cell phones and pagers or set ringers to silent mode. ROSSINI, IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA: OVERTURE If the music of Rossini’s overture to Il barbiere di Siviglia (THe Barber of Seville) seems to have a peculiar amount of swashbuckling surge and vigor for a comic opera prelude, it is because the overture originally was composed for an earlier opera, Aureliano in Palmira, a historical work based on the Crusades. In fact, it is believed that Rossini used this music two other times be- fore this opera. The composer’s recycling provides an interesting contrast with Beethoven, who composed four different overtures before arriving at a final version for his only opera,Fidelio . The once-perceivedSturm und Drang of Rossini’s overture has been blunted by association, not only by the composer’s accompanying setting of the Beaumarchais comedy, but also by its jocular appearances in a Bugs Bunny cartoon, the Beatles’ filmHelp , and an episode of Seinfeld. -

Senior Recital Program

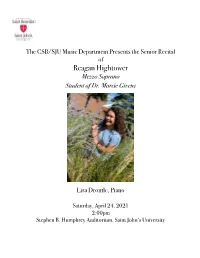

The CSB/SJU Music Department Presents the Senior Recital of Reagan Hightower Mezzo Soprano Student of Dr. Marcie Givens Lisa Drontle, Piano Saturday, April 24, 2021 2:00pm Stephen B. Humphrey Auditorium, Saint John’s University Program “An die Musik” Franz Schubert (1797-1828) “Ständchen” Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) “Liebeszauber” Clara Wieck Schumann (1819-1896) “Crépuscule” Jules Massenet (1842-1912) “Notre amour” Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) *5-minute intermission* “El Majo Timido” Enrique Granados (1867-1916) “Voi che sapete” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart from le Nozze di Figaro (1756-1791) “Tired” Ralph Vaughn Williams from Four Last Songs (1877-1953) “Silent Noon” Ralph Vaughn Williams (1877-1953) “Let Me Be Your Star” Marc Shaiman from SMASH (b.1959) featuring Emily Booth, mezzo soprano Translations, Texts, and Notes “An die Musik” “To Music” Du holde Kunst, in wieviel grauen Stunden, Beloved art, in how many a bleak hour, Wo mich des Lebens wilder Kreis umstrickt, when I am enmeshed in life’s tumultuous Hast du mein Herz zu warmer Lieb round, entzunden, have you kindled my heart to the warmth of Hast mich in eine bessre Welt entrückt! love, and borne me away to a better world! Oft hat ein Seufzer, deiner Harf entflossen, Ein süsser, heiliger Akkord von dir Often a sigh, escaping from your harp, Den Himmel bessrer Zeiten mir erschlossen, a sweet, celestial chord Du holde Kunst, ich danke dir dafür! has revealed to me a heaven of happier times. Beloved art, for this I thank you! Despite his brief life, Franz Schubert composed over 600 lieder (German Art Song). -

Mise En Page 1

CARL ORFF CARMINA BURANA Y. SUH - Y. SAELENS - T. BAUER ANIMA ETERNA BRUGGE COLLEGIUM VOCALE GENT CANTATE DOMINO JOS VAN IMMERSEEL, dir. ZIG-ZAG TERRITOIRES - ZZT353 TERRITOIRES ZIG-ZAG CARL ORFF ZZT CARMINA BURANA 353 Y. SUH - Y. SAELENS - T. BAUER ANIMA ETERNA BRUGGE COLLEGIUM VOCALE GENT CANTATE DOMINO JOS VAN IMMERSEEL, dir. Probably no other work in music history has inspired Aucune œuvre dans l’histoire de la musique n’a sans such polemic as Carl Orff’s scenic cantata Carmina doute suscité autant de polémiques que les Carmina Burana (1936): an energetic ode to life and love - Burana, cantate scénique de Carl Orff (1936) : une ode adored by millions, deemed simple and bombastic à la vie et à l’amour d’une immense énergie – adorée by others. No wall of sound or mass of strings on this par des millions d’auditeurs, méprisée par d’autres recording though: Anima Eterna Brugge returns to comme une musique excessivement simple et pom- the score, turns up an impressive battery of percus- peuse. Dans cet enregistrement, on n’entendra pas de sionists and winds, and takes the stage with its ex- sonorité écrasante ni de quantité massive d’instru- quisite musical partners for a transparent, sensuous ments à cordes : Anima Eterna Brugge revient à la partition originale, fait appel à une batterie impres- and invigorating performance that breathes new life sionnante de percussions et d’instruments à vents et into a classical icon. impose, avec ses remarquables partenaires musicaux, une interprétation transparente, sensuelle et tonique qui insuffle une nouvelle vie à cette œuvre culte. -

College Band Directors National Association North Central Division Conference

COLLEGE BAND DIRECTORS NATIONAL ASSOCIATION NORTH CENTRAL DIVISION CONFERENCE February 20 - 22, 2020 Holtschneider Performance Center 2330 North Halsted Street • Chicago Ronald Caltabiano, DMA, Dean Friday, February 21, 2020 • 10:00 AM CHOSEN GEMS WITH DEPAUL UNIVERSITY WIND SYMPHONY Dr. Erica Neidlinger, conductor Mary Patricia Gannon Concert Hall 2330 North Halsted Street • Chicago Friday, February 21, 2020 • 10:00 AM Gannon Concert Hall CHOSEN GEMS WITH DEPAUL UNIVERSITY WIND SYMPHONY Dr. Erica Neidlinger, conductor PROGRAM Yo Goto (b. 1958) Songs for Wind Ensemble (2009) Christopher Heidenreich, conductor Carl Orff (1895-1982); trans. Hermann Regner Four Burlesque Scenes from Der Mond (1939/1997) I. Dance of the Peasants in the Tavern II. “The Moon is gone” III. “Oh, look there hangs the Moon” IV. “The Wine is good, the Moon so clear” James Ripley, conductor Gordon Jacob (1895-1984) Fantasia on an English Folk Song (1984) Devin Otto, conductor Bernard Gilmore (1937-2013) Five Folk Songs for Soprano and Band (1967/2002) I. Mrs. McGrath II. All the Pretty Little Horses III. Yerakina IV. El Burro V. A Fiddler Matthew Schlomer, conductor CHOSEN GEMS WITH DEPAUL WIND SYMPHONY • FEBRUARY 21, 2020 PROGRAM Antonio Gervasoni (b. 1973) Peruvian Fanfare No. 1 (2014) Glenn Hayes, conductor Andrew David Perkins (b. 1978) Until the Night Collapses (2018) Michael King, conductor Jodie Blackshaw (b. 1971) Peace Dancer (2017) John Stewart, conductor Healey Willan (1880-1968); Ed. William Teague Royce Hall Suite (1949) I. Prelude and Fugue II. Menuet III. Rondo Daniel Farr, conductor CHOSEN GEMS WITH DEPAUL WIND SYMPHONY • FEBRUARY 21, 2020 BIOGRAPHIES Dr. Erica J. -

The Horrified Contemplation of Death Was A

Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth) Gustav Mahler he horrified contemplation of death was a least initially, he imagined the work as being Tcentral experience in Gustav Mahler’s life. performable in versions with the two solo- The subject weighed heavily on him as he ists and either orchestra or piano, the piano composed Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of version being considered a full equal of the the Earth). He had not begun to recover from orchestral setting rather than a poor relation. the shock of his four-year-old daughter’s re- He did go on to compose a Ninth Symphony; cent passing when, in the summer of 1907, fatefully, it would be his last, and his Tenth his physicians informed him that he was remained an incomplete fragment. suffering from a heart condition that would A friend had presented Mahler with Die probably prove fatal. They advised him to chinesische Flöte (The Chinese Flute), a col- give up all strenuous activity, including the lection of Chinese poems assembled and conducting by which he earned his liveli- translated into German by Hans Bethge — hood and the hiking from which he derived more accurately described as poetic para- spiritual nourishment. He wrote to his friend phrases than literal translations of the T’ang Bruno Walter: Dynasty texts. Their basic philosophy both reflected Mahler’s death fears and offered a At a single stroke, I have lost any calm and measure of consolation. The message is that peace of mind I ever achieved. I stand now nature — the earth — goes on, perpetually face to face with nothingness, and now, at renewing itself, but that man’s experience of the end of my life, I have to begin to learn it is limited to a brief span. -

46Th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES

th SEASON PROGRAM NOTES 46 Week 5 August 12 – 18, 2018 Sunday, August 12, 6 pm very few dynamic indications (Mozart was Composed in memory of Popper’s publisher apparently content to leave such decisions Daniel Rahter, the Requiem projects an WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART to his performers), but the movement does appropriately somber and consoling mood. (1756 – 1791) close quietly on the dotted figure that The brief piece is distinctive for the rich Sonata in B-flat Major for Bassoon & Cello, has figured prominently throughout. The sonority of the three solo cellos, and in its K. 292 (1775) Andante, in F Major, offers long singing serious and dark sound the Requiem is often lines for the bassoon; the movement is in reminiscent of the music of Popper’s friend When Mozart and his father visited Munich binary form, and Mozart offers the option to Johannes Brahms. The Requiem opens with in the first months of 1775 for the premiere repeat both halves. The concluding Allegro the three cellos alone, laying out the dotted of the boy’s opera buffa La finta giardiniera, is a cheerful rondo based on the bassoon’s main idea, which soon passes among the they found themselves the toast of the city’s energetic opening tune. This Sonata is never three soloists. While it rises to a full-throated musical life. The opera was a success, they really difficult (Mozart was aware that he climax, this is not extroverted or virtuosic conducted concerts, and were invited to was writing for amateur musicians), but music. It remains lyric and expressive masked balls, and there was much attention this is certainly the most extroverted of throughout, and Popper constantly reminds paid to the talents of Wolfgang, who turned the movements—full of trills, syncopated his performers: dolce, espressivo, and 19 while he was in Munich.